Ricardo Rada Peral

Ricardo Rada Peral | |

|---|---|

| Born | 5 February 1885 |

| Died | 8 June 1956 (aged 81) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | professional officer |

| Known for | military |

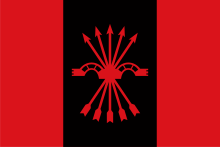

| Political party | Falange, Carlism |

Ricardo Rada Peral (5 February 1885 - 8 June 1956) was a Spanish officer, who rose to the rank of lieutenant general. In the 1910s and 1920s he spent 12 years in Morocco, both on combat missions and garrison service; during the Spanish Civil War he sided with the Nationalists and commanded units up to a corps. In the 1940s he was the first commander of the first Spanish armored division. His highest army assignment was command of the II. Military Region (Seville) in 1946-1952. He is best known as instructor and de facto leader of paramilitary militias of the Falangists (Primera Línea) in 1933-1934 and the Carlists (Requeté) in 1935-1936. Until the 1930s he did not engage in politics; later following a brief period in Falange Española he joined Comunión Tradicionalista and entered the top Carlist wartime executive. In the late 1930s he fully identified with the Francoist regime and abandoned other party activity.

Family and youth[edit]

Rada descended from an Andalusian family of military traditions. His paternal grandfather, Ricardo Rada Martínez from Granada[2] (died 1900)[3] served in Guardia Civil. He fought during the Hispano-Moroccan war and during the Third Carlist War in the Alfonsist ranks; he received military honors for his contribution to defense of Bilbao and other campaigns.[4] Since the late 1870s he held numerous high Guardia Civil positions in Andalusia[5] and retired as a highly decorated coronel subinspector of the Benemérita.[6] At unspecified time he married Nicolasa Cortines Espinosa de los Monteros;[7] they had 5 children.[8] One of them was the father of Ricardo,[9] most likely the oldest of the siblings, Ricardo Rada Cortines (1858[10]-1923[11]). He also joined Guardia Civil,[12] but later moved to infantry; in 1888 he served as teniente,[13] in 1903 he was comandante,[14] in 1911 he rose to teniente coronel,[15] and he retired as general de brigada. He married Natalia Peral Obispo[16] (1861[17]-1946[18]), daughter to a landholder family from Guadix;[19] she later inherited real estate in Fiñana[20] and Abla.[21]

The couple had 9 children, Ricardo born as the second oldest and the first son.[22] There is close to nothing known about his childhood, probably spent in the maternal estates; in the late 1890s he was already a boarder at the Instituto Provincional in Almeria.[23] Relatively late at the age of 21[24] he commenced the military career; in 1906 Rada entered the infantry academy in Toledo.[25] He progressed in line with the standard curriculum and graduated in 1909; he was nominated to the lowest officer rank, segundo teniente. His first assignment was to Badajoz, where in 1909 he commenced regular garrison duties.[26]

In 1911 Rada married Presentación Martínez Martínez;[27] her father Juan Manuel Martínez Alcalde was the landowner from Huéneja.[28] Ricardo and Presentación had 5 children, born between the early 1910s and the early 1920s.[29] Ricardo[30] and Francisco Rada Martínez joined the army and served in Nationalist troops during the civil war;[31] the former later specialized as engineer and in the early 1970s he was subdirector general de Montes de España,[32] the latter became a military and then a civilian doctor.[33] Juan was a lawyer[34] and Manuel[35] an official. María died in 1921 at 3 years of age.[36] Among other Rada’s relatives, his brothers José and Rafael became officers; the former died in 1920,[37] the latter in 1924 in Morocco.[38] Two of his sisters also passed away prematurely, Rosario in 1899[39] and Dolores in 1920.[40] The other four, Francisco, Eduardo, Ramón and Juana, did not become public figures.[41] Some authors claim that Ricardo “was descendant” to a well-known Navarrese Carlist military Teodoro Rada Delgado (1822-1874),[42] but data hardly match;[43] it appears to be an ex-post attempt to enhance Rada’s links to Carlism.[44]

Junior officer[edit]

Rada served in Badajóz for some 2 years before in 1911 he was promoted to primer teniente de infantería.[45] He apparently considered joining Guardia Civil, but in 1912 for unclear reasons he was removed from the list of candidates and posted to 10. Regimiento de Infantería de Córdoba.[46] Following 1 more year of garrison service in 1913 he was posted to Morocco. His first spell lasted slightly over a year, between the summer of 1913 and the autumn of 1914; it fell on the war period known as Campaña de Yebala.[47] Rada’s exact unit is not known. Initially shortly after arrival and due to illness he was hospitalized in Ceuta. He returned to line in early 1914, commencing a very intense spell of combat missions, first at Rincón de Medik at the outskirts of Tetuan and then during few other engagements in the hinterland, known as skirmishes at Malalien, Río Martín and Loma Amarilla.[48] In September 1914 he was assigned to 5. Infantry Regiment del Infante in Zaragoza.[49] In 1915 he received the first military honor, Cruz del Mérito Militar 1st class.[50] In early 1916 Rada was promoted to capitán de infantería, though “por antigüedad” and not “por méritos de guerra”.[51] The 1916 military annual lists him among officers of 2. Regiment da la Reina in Larache, but it is not clear whether he indeed returned to Africa.[52] The same year he assumed duties in the 18. Regiment in Almería,[53] where in 1917 he was decorated with Medalla Militar de Marruecos.[54]

Rada served in Almería between 1918 and 1919.[55] In 1920 he was back in Africa, listed as officer of the 2. Regimiento de Madrid, stationed in Ceuta.[56] His second spell in Morocco lasted over 2 years, between 1921 and 1923. It is known that with an unspecified regiment he took part in the Battle of Annual in 1921; his unit survived the carnage and was sent to Melilla as reinforcements. In late 1921 he assumed command of 4. Compañía del Batallón Expedicionario of the 5. Infantry Regiment. On this position he took part in numerous combat actions; during one of them he was personally leading a bayonet charge. Some of the missions were defensive operations carried out as protection of own logistical lines, some were frontal assault engagements, and some were sieges of enemy strongholds; during different spells Rada served under command of Emilio Barrera, Federico Berenguer, José Sanjurjo and Miguel Campins.[57] Following one more period in hospital and a brief period in 71. Regimiento de La Corona in Almeria in 1922,[58] in 1922-1923 he kept serving on combat, policing and convoy protection missions[59] with La Corona,[60] mostly in eastern part of the protectorate. e.g. near Taza or Nador. Some included fierce and hardly successful battles, like the attempt to seize control over the area known as Zoco el Jemis de Beni-Bu-Ifrur. In 1922 his regiment received Medalla Militar Colectiva. In August 1923 Rada was promoted to comandante, this time for combat merits.[61]

Senior officer[edit]

Following the coup of Primo de Rivera in 1923, the dictator dispatched military inspectors (delegados gubernativos) to reform local government and instill patriotism in the population;[62] they were expected to root out the patronage networks of caciques and catalyze the emergence of new, prototypical Spanish citizen. In December 1923 Rada was nominated to such a role[63] and assigned to the Almerían district of Vera;[64] he kept building local primoriverista structures, like Somatén.[65] One scholar claims that instead of fighting caciquismo, Rada sided with one of the local factions.[66] In general, the concept of delegados gubernativos attracted increasing criticism; some claimed that it backfired by alienating local population and generating animosity towards the army. Since mid-1924 Primo started to withdraw his delegados;[67] in 1924 Rada was recalled to Morocco.[68]

The third Rada’s spell in Africa was the longest one and lasted almost 7 years, though out of these only 3 years were on combat missions. This time he was posted to the freshly formed Spanish foreign legion, known as Tercio de Extranjeros. His bandera saw action mostly in eastern Morocco,[69] where Rada was noted by his superiors as “distinguiéndose siempre en cuantos momentos fue empleado, por su valor frío, rayano en el estoicismo, honrándose de haberlo tenido bajo su mando” and noted in the press.[70] He was wounded and following treatment in the Almería hospital he returned to line, again wounded and this time treated in Tetuán until the spring of 1925. He then assumed command of 7. Bandera and then the 1. Bandera. In 1926 he took part in the Alhucemas landing;[71] in 1925-1926, he either reported to or closely co-operated with Francisco Franco,[72] Agustín Muñoz Grandes and Emilio Mola. Since 1927, Rada was commanding larger battle formations which included 2 banderas and auxiliary sub-units. At the time he was awarded Cruz de 2ª Clase del Mérito Militar, Cruz de 2ª Clase de María Cristina and Cruz de 2ª Clase del Mérito Naval.[73]

In 1927, the Spanish army suffocated the rising, and fighting in the protectorate ceased. Rada was given command of the Touima garrison near Nador, composed mostly of the 1. Tercio of the Legion. In 1928, he received the French Legion of Honour; the following year he was granted Medalla Militar Individual for his service in the mid-1920s. In 1929, he was already teniente coronel.[74] Following the advent of the Republic in 1931, Rada initially received some minor further honors, but his situation changed when the government of Manuel Azaña embarked on major reform of the army. One of its objectives was to scale down what was perceived as an overgrown officer corps; the government deployed a scheme, partially forcing and partially encouraging officers to retire. It is not clear what mechanism worked for Rada; in June 1931, he passed from active service to reserve; the same year he left Morocco.[75] As a 46-year-old pensioner, he settled in Almería;[76] later he took up a job at Compañía Tabacalera.[77]

Early conspiracy[edit]

Data on Rada’s fate during the republican period is confusing and at times contradictory. The uncontested information is that politically he initially tended to sympathize with the local Almería branch of Acción Popular.[78] However, during 1932-1933, he underwent rapid radicalization and since then scholars associate him with extreme right organisations.[79] Few claim that already at this stage he joined the Carlists,[80] but the prevailing opinion is that he rather opted for the nascent Falange Española. He either moved to Madrid or visited the capital frequently, and was often seen during meetings at the Ballena Alegre café, along the likes of Emilio Rodríguez Tarduchy or Luis López Pando.[81] At least since 1934 on Falangist rallies, he appeared among top personalities, be it Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera or Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta.[82] It is not clear what was his formal position within the party.[83] According to some sources, it was so high that he greatly influenced appointments of jefes provinciales or even entire provincial executive bodies, at least in Andalusia.[84]

At some point in 1933 or 1934, Rada got involved in buildup of the Falangist shirt branch; it was officially known as Primera Línea. According to some sources, he became the key man behind the organisation;[85] others tend to agree, but note that formally and jointly with Román Ayza, he was one of two deputy commanders (“auxiliares”), while head of the branch was Luis Arredondo.[86] At Primera Línea, Rada was instrumental when forming and training the Falangist militia, including teaching them “elementary facts about handling weapons”.[87] However, over time some differences developed between Rada and other FE leaders. Some scholars consider him “more independent” and distinguish him from “staunch supporters”;[88] others are more specific and list Rada among “monárquicos alfonsinos”; eventually in early 1935 this group – with Rada and Juan Antonio Ansaldo its best known representatives – resigned and left Falange.[89]

In late 1933, Rada engaged in other organisation, a semi-clandestine Unión Militar Española; its format was a hybrid between political pressure group and a corporative structure, sort of a trade union within the army. He was among 7 members of its Consejo Ejecutivo;[90] some scholars list him, after Bartolomé Barba Hernández and along Rodríguez Tarduchy, Luis Arredondo Acuña and Gumersindo de la Gándara Morella the key man in the UME decision-making command layer.[91] None of the sources consulted provides exact information on his contribution to the UME stand and its course towards the governmental policy. However, he is listed as a prominent person who in 1934-1936 labored to forge and then maintain contacts with political parties, apart from Falange also with the Alfonsists (Antonio Goicoechea, José Calvo Sotelo) and the Carlists (Manuel Fal Conde, José Luis Zamanillo).[92] During final months of the Republic, Rada clearly advanced conspiracy against the regime, including violent action and potentially a coup.[93]

Carlist conspiracy[edit]

Some scholars claim that Rada approached Carlism when he was still related to Falange or that he trained militias of both groupings simultaneously;[94] one author even maintains that he was first working for the Carlists, then moved to FE and then returned to Comunión Tradicionalista.[95] The dominating view, however, is that Rada joined the Traditionalists some time in early 1935. Like in Falange, his focus was on training the party militia, Requeté. According to some authors, the previous commander, Enrique Varela, returned to active military service and officially had to resign as Jefé Nacional; he continued as de facto commander, but formally his role was taken by Rada.[96] Others claim he was Varela’s deputy,[97] while most claim that Rada replaced Varela.[98] He was assigned a title of Inspector General del Requeté.[99] Rada proved vital for further Carlist military buildup;[100] in late spring of 1936, Requeté grouped 10,000 fully armed and trained men plus 20,000 forming an auxiliary pool.[101] In contrast to urban-oriented action groups "primarily accustomed to street fighting and pistolerismo", maintained by other parties,[102] Requeté was a "genuine citizen army" capable of performing small-scale tactical military operations.[103]

Since mid-1935, Rada was openly present at Carlist public gatherings, e.g. in Catalonia;[104] the Republican security services tried to watch him closely.[105] In general elections of February 1936, he stood as a Carlist candidate within the Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria coalition in Almería,[106] but failed.[107] Afterwards, he fully dedicated himself to technical plans of a Requeté military action,[108] though it is not clear whether as professional officer he indeed supported a ruritanian plan of Carlist-only rising,[109] developed and prepared in May and June 1936.[110] In the spring, he was appointed member of freshly-created Junta Técnica Militar, headed by Mario Muslera;[111] the body was formed by professional officers, apart from Rada also by Alejandro Utrilla, Eduardo Baselga and José Sanjurjo, son of the exiled general.[112] According to some, he headed so-called sección interna.[113]

Since June 1936, Rada was hectically active tying the knots of the conspiracy, both from the Carlist and from the UME end.[114] Mola nominated him to co-ordinate UME preparations in Almeria and neighboring provinces,[115] which he did ensuring also the Traditionalist presence in the plans.[116] Within Carlism, his focus was on Navarre;[117] he toured the region personally visiting minor towns and making sure all was ready for the rising.[118] Historians think him a man which “proved an invaluable link between the Communion and the conspiring officers”.[119] He represented a different strategy than the Traditionalist leader, Fal; the latter intended to close a political deal with the military before committing requetés, Rada preferred the opposite.[120] Rada was reportedly “visibly chafing at the delay caused by Fal Conde’s obduracy” and eventually he formed a dissenting group, which cornered Fal and pressured him to declare Carlist participation with no tangible commitments on part of Mola.[121]

Civil War[edit]

During the July 1936 coup, Rada resided in Navarre; following smooth seizure of the region, as second in command of a rebel column led by Francisco García Escámez, he left Pamplona. Having suffocated a resistance island in Logroño[122] on July 22 they reached Sierra de Guadarrama and engaged in combat for control of mountain passes.[123] After a local breakthrough, his troops reached Braojos, but failed to advance further.[124] In August and September, Rada led his men in the Navafria sector fighting for Puerto de Lozoya; he was promoted to full coronel. In November, his units crossed Navalperal and Fresnedellas;[125] in Brunete, he joined the units of Varela. In December, he set his HQ in Leganés.[126] Since early 1937, Rada was commanding mixed units comparable to a brigade, including requetés but also the Moroccans.[127] His men seized Cerro de los Angeles and then Vaciamadrid. In February and March, he was crucially involved in the Battle of Jarama.[128] In April he took command of 2. Brigade from 4. Division.[129]

In the summer of 1936, Rada was nominated to the wartime Carlist executive, Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra; as head of requetés he formed part of its Sección Militar.[130] Following death of the Carlist king Alfonso Carlos back in 1936, Rada declared full loyalty to the new dynastic leader, Don Javier.[131] However, he demonstrated no reluctance when Comunión Tradicionalista was forcefully merged into a new state party, Falange Española Tradicionalista; in May 1937, he was nominated one of 2 deputy commanders[132] of the new, combined FET militia.[133] He was among some 10 top Carlists in the FET structures.[134] Some episodes suggest that within FET he tried to assure Carlist domination,[135] but the evidence is not clear.[136] Following nomination he left his troops for Salamanca, but his role of militia commander was formal.[137] In June he flew to Africa to raise the 152. Division in Tetuan.[138] In July 1937, Rada was nominated Gobernador Militar de Cáceres[139] and commanded the provincial frontline, relying mostly on the 152. Division.[140] As governor, he was responsible for harsh repressive measures.[141]

In March 1938, Rada was released from his Cáceres duties; his 152. (which included Carlist units of Tercio de Cristo Rey and Tercio de Alcazar)[142] was deployed at the confluence of Soria, Zaragoza and Guadalajara provinces.[143] Following some combat in May, they moved to the Calatayud sector;[144] Rada was promoted to Brigadier.[145] In late spring he led advance across northern Aragon[146] and in late May set his HQ in Tremp, already in Catalonia.[147] In August the division was shuttled to the Ebro bend and took part in fierce combat across key sectors, including Villalba dels Arcs, Vertice Gaeta,[148] and then in September and October in Sierra de Fatarrella.[149] In November 1938, Rada assumed command of Cuerpo de Ejército Marroquí; with his HQ in Batea and then Montanejos, he took part in failed assaults towards the Valencian plains. At the war’s end, his corps reached the outskirts of Valencia.[150]

Post-war career[edit]

In late 1939, Rada temporarily assumed command of Cuerpo de Ejército de Castilla;[151] later he ceded the 152. and assumed command of 13. Division,[152] based in Barcelona. He was also nominated inspector of armored troops,[153] a branch hardly existent in the Spanish army and composed mostly of the captured ex-Soviet T-26 vehicles. A spate of honors followed,[154] with Medalla de Campaña, Cruz Roja del Mérito Militar, and two Cruces de Guerra.[155] In 1940, he was nominated Presidente de la Sociedad de Socorros Mutuos del Arma de Infantería.[156] The same year he visited Nazi Germany learning from tank warfare experiences in Poland[157] and was awarded the Verdienstorden vom Deutschen Adler, apart from Portuguese and Italian honors received later.[158] In 1941, he was nominated vocal suplente in Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo; it is not clear how long he served.[159] In 1942, Rada was promoted to division general;[160] in 1943 he ceased as jefe of 13. Division and assumed command of División Acorazada, the first armored division in the Spanish army. At this post, he served until 1945.[161]

During short spells in the mid-1940s, Rada acted as caretaker commander of I. Región Militar (Madrid); in 1945, he became commander of Cuerpo de Ejército de Maestrazgo.[162] In 1946, he was promoted to teniente general and took command of II. Región Militar (Seville) and Cuerpo de Ejército de Andalucia.[163] This proved the highest position in his military career, the one he held for an unusually long period of 6 years until 1952; that year he relinquished command of a tangible force and assumed management of Museo del Ejército. Though in 1955 he passed to reserve, Rada headed the museum until his death.[164]

There is little information on Rada’s post-war political allegiances. He appeared to have been loyal to Franco, did not sign letters pressing monarchist restoration, was admitted at personal audiences in 1939, 1945, 1946 and 1952, and in 1948 received Gran Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Civil, one of the highest decorations available. However, within Falange he was considered a reactionary monarchist and a representative of an oligarchy which aimed at “restauración social”.[165] In the early 1940s, he secretly conferred with the Carlists possibly up to the point of mounting some schemes.[166] The Francoist security[167] reported with unease that during Semana Santa in Granada a fully uniformed requeté unit paraded across the city saluted on tribune by Utrilla and Rada.[168] Another report claimed that Carlists operated a front organisation directed by Tomás Lucendo Muñoz, “persona de la confianza del General Rada”.[169] Some scholars claim that in the early 1940s, he was “el general de ideología carlista más significado y de mayor pedigrí tradicionalista de todo el ejército”.[170] However, no work on Carlist history in the post-war era mentions Rada as involved,[171] and it seems that though he might have nurtured some Traditionalist sympathies, politically he got fully integrated with the Francoist regime.

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ none of the sources consulted provides information on location of his birth, especially that none of his parents was related to Málaga. Most likely in the mid-1880s his father served in an infantry unit in Málaga

- ^ Ricardo de Rada Martínez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ for a brief obituary note see Cronica Meridional 27.04.00, available here

- ^ see his decorations, listed in Crónica Meridional 27.04.00, available here

- ^ e.g. for Cadiz see La Epoca 28.02.77m available here

- ^ Crónica Meridional 27.04.00, available here

- ^ Ricardo de Rada Martínez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here, also (her segundo apellido spelled as "Cortinez") in Crónica Meridional 27.04.00, available here. In the press note from either 1900 or 1901, however, already as a widow, she is referred to as "Nicolasa Cortinas Castello", El Regional [no date, after September 1900], available here

- ^ or at least 5 are listed in the death notice, Crónica Meridional 27.04.00, available here

- ^ he was born in Chiclana de la Frontera, probably during the Guardia Civil assignement to the town of his father, Ricardo de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Ricardo de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ La Independencia 12.12.23, available here

- ^ in 1884 he was noted as capitan, Cronica Meridional 01.01.84, available here

- ^ El Correo Militar 28.06.88, available here

- ^ El Regional 07.11.02, available here

- ^ El Popular 06.01.11, available here

- ^ El Ferro-carril 16.09.99, available here

- ^ Natalia Peral Obispo, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ ABC 12.06.46, available here

- ^ she was daughter to Manuel Peral Cuevas and María Manuela Obispo Morales, Natalia Peral Obispo, [in:] Geneanet service, available here. Her father owned also a vinegar manufacture, Annuario del comercio, de la industria, de la magistratura y de la administracion 1894, p. 778, available here

- ^ La Informacion 17.08.11, available here. The estate, known as "Haza del Riego", later became the property of Rada, Francisco Manuel López López, El episodio de la Guardia Civil de Abla y Fiñana en Julio de 1936, [in:] Monica Fernández Amador Ied.), La Guerra Civil española 80 años después. Las investigaciones en la provincia de Almería, Almeria 2016, available also here

- ^ Cronica Meridinal 05.09.15, available here

- ^ an unnamed daughter was born in last days of 1883,Cronica Meridional 01.01.84, available here

- ^ Cronica Meridional 08.06.90, available here

- ^ typical age for entering the cadet corps in Toledo was late teens; Rada's whereabouts in the 1900-1905 are not clear. In 1905 he was mentioned as a student in Academia de Bellas Artes in Almeria, El Radical 03.10.05, available here. It is not clear whether a penchant for arts was related to journeys to Paris, reported for Rada Cortines "and his sons" in late 1905 and early 1906, see e.g. Cronica Meridional 20.10.05, available here

- ^ José Martín Brocos Fernández, In memoriam Teniente General Ricardo de Rada y Peral. Primer General Jefe de la Acorazada Brunete, [in:] Arbil 116 (2008)

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008. However, contemporary press claimed that as segundo teniente in 1910 Rada was posted to detachment of the Cordoba regiment, stationed in Granada, 'Cronica Meridional 27.01.10, available here

- ^ Cronica Meridional 08.01.11, available here

- ^ her parents were Juan Manuel Martínez Alcalde and María Martínez Cardenas, La Independencia 01.03.21, available here. For his property see Cronica Meridional 03.03.13, available here

- ^ Ricardo de Rada y Peral, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Ricardo de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Ricardo was initially detained by the Republicans; he managed to escape, made it to the Nationalist zone, served in Requete and then commanded other units

- ^ Diario de Burgos 20.10.71, available here

- ^ Francisco de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Juan de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Manuel Victor de Rada Martinez, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ La Independencia 01.03.21, available here

- ^ La Independencia 27.03.20, available here

- ^ La Libertad 13.11.26, available here

- ^ El Ferro-carril 16.09.99, available here

- ^ La Independencia 29.12.21, available here

- ^ Francisco and Eduardo are mentioned in La Independencia 22.07.22, available here. However, none of them is listed in a later obituary note; instead, there is a Ramón mentioned, along a sister named Africa, La Independencia 12.12.23, available here

- ^ see e.g. José Sanz y Díaz, Generales carlistas, vol. I, Madrid 1954, pp. 3, 24, or Luis Rubio Hernansáez, Contrarrevoluciones católicas: de los chuanes a los cristeros (1792-1942), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9786078472680, p. 120. Some authors even claim that he was “son of a Carlist general”, Francisco J. Romero Salvadó, Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War, Plymouth 2007, ISBN 9780810880092, p. 273

- ^ his grandfather Ricardo Rada Martinez (year of birth unknown) became a father no later than in 1858, so he must have been born in 1840 latest; this makes him an unlikely son of Teodoro Rada, born in 1822. Besides, Teodoro was a Navarrese while Rada Martinez was an Andalusian. Last but not least, in the Third Carlist War Teodoro Rada joined the Carlists, while Rada Martinez served in the Alfonsist ranks. As both fought during the siege of Bilbao (when Teodoro Rada was killed in action), theoretically they might have actually met

- ^ the first identified instance of the claim that Rada Peral was descendant to Teodoro Rada is in the 1954 book by a Carlist writer, José Sanz y Díaz

- ^ Cronica Meridional 08.01.11, available here

- ^ La Mañana 14.12.12, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1915, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1916, available here

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1917, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1919, available here

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1920, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1922, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Anuario Militar de España 1923, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Richard Gow, Patria and Citizenship: Miguel Primo de Rivera, Caciques and Military Delegados, 1923–1924, [in:] Susana Bayó Belenguer, Nicola Brady (eds.), Pulling Together or Pulling Apart? Perspectives on Nationhood, Identity, and Belonging in Europe, Oxford 2019, ISBN 9781789976755, pp. 147-176

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008, also Pedro Martínez Gómez, La dictadura de Primo de Rivera en Almería (1923-1930). Entre el continuismo y la modernización, Almeria 2007, ISBN 9788482408743, p. 165

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Martínez Gómez 2007, p. 323

- ^ Pedro Martínez Gómez, Los apoyos políticos a la dictadura de Primo de Rivera: la Unión Ciudadana de Mojácar, [in:] Axarquía 8 (2003), p. 42. The same author in another work claims that Rada's arrival "no provoca variación alguna", Pedro Martínez Gómez, Dictadura de Primo de Rivera en Vera, [in:] Axarquia 5 (2000), p. 93

- ^ their number was being reduced between late 1924 and 1927 from the peak of 523 to merely 79, Gow 2019, p. 176

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ near Talambo, José E. Alvarez, The Betrothed of Death: The Spanish Foreign Legion During the Rif Rebellion, 1920-1927, London 2001, ISBN 9780313073410, p. 123

- ^ La Correspondencia Militar 26.06.25, available here

- ^ according to some authors “he led the Alhucemas Bay landing”, Romero Salvadó 2013, p. 273

- ^ Alvarez 2001, p. 172. In 1935, during anniversary of the promotion, Franco honored Rada with a personal embrace, La Independencia 10.11.35, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ La Nacion 06.11.29, available here

- ^ premature retirement was forced also upon some other officers involved in Carlism, like Alejandro Utrilla Belbel and Ignacio Romero Osborne

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Cronica Meridional 18.04.34, available here; already his father was related to the company, see Cronica Meridional 16.04.89, available here

- ^ Rafael Quirosa-Cheyrouze y Muñoz, Católicos, monárquicos y fascistas en Almería durante la Segunda República, Almeria 1998, ISBN 9788482401195, p. 54

- ^ Victor Manuel Arbeloa, El quiebro del PSOE (1933-1934): Del gobierno a la revolución, Madrid 2015, ISBN 9788415705666, p. 47

- ^ Arbeloa 2015, pp. 47-48

- ^ Pilar Primo de Rivera, Recuerdos de una vida, Madrid 1983, ISBN 9788486169060, p. 55

- ^ e.g. during a rally against Companys in October 1934, Joaquín Arrarás, Historia de la Cruzada Española, Vol. II, Madrid 1984, ISBN 9788486349004, p. 133. Later he was with Jose Antonio attending the funeral of a dead falangist, Rafael García Serrano, La gran esperanza, Barcelona 1983, ISBN 9788432056833, p. 17

- ^ none of the sources consulted clarifies what was Rada's formal position in Falange. He was not member of the provincial Almeria executive, composed of 6 individuals, see Oscar Rodríguez Barreira, Miserias del poder. Los poderes locales y el nuevo Estado franquista 1936-1951, Valencia 2013, ISBN 9788437093345, chapter Profetas de la nacion herida

- ^ Sofía Rodríguez López, La sección femenina y la sociedad almeriense durante el franquismo, Almeria 2005, ISBN 9788482407586, p. 73

- ^ Paul Preston, El holocausto español, Madrid 2017, ISBN 9788466339483, p. 47

- ^ Roberto Muñoz Bolaños, Escuadras de la muerte: militares, Falange y terrorismo en la II República, [in:] Amnis 17 (2018) [version online]

- ^ Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, London 2013, ISBN 9780718192938, p. 77

- ^ Joan Maria Thomàs, José Antonio Primo de Rivera: The Reality and Myth of a Spanish Fascist Leader, London 2019, ISBN 9781789202090, p. 130

- ^ Maximiliano García Venero, Historia de la Unificacion, Madrid 1970, p. 23

- ^ at least according to his own statement, Declaración de testigo de Ricardo de Rada Peral, general de division, [in:] Pares service, available here, p. 3

- ^ Rafael Dávila Álvarez, La Guerra Civil en el norte: El general Dávila, Franco y las campañas que decidieron el conflicto, Madrid 2021, ISBN 9788413841281, p. 22

- ^ Declaración de testigo de Ricardo de Rada Peral, general de division, [in:] Pares service, available here, p. 4

- ^ Antonio Atienza Peñarrocha, Africanistas y junteros: el ejercito español en Africa y el oficial José Enrique Varela Iglesias [PhD thesis Universidad Cardenal Herrera – CEU], Valencia 2012, pp. 926, 945

- ^ Preston 2017, p. 47

- ^ Eduardo Gonzalez Calleja, Julio Aróstegui Sánchez, La tradición recuperada. El Requeté carlista y la insurrección, [in:] Historia contemporánea 11 (1994), p. 49

- ^ Eduardo González Calleja, Paramilitarització i violencia politica a l’Espanya del primer terc de segle: el requeté tradicionalista (1900–1936), [in:] Revista de Girona 147 (1991), p. 70, also Gonzalez, Aróstegui 1994, p. 37, Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294, p. 222

- ^ “to all intents and purposes Varela’s deputy”, even if nominated National Inspector of the Requeté, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 222

- ^ Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 322, Joaquín Arrarás, Historia de la Segunda República Española, Madrid 1965, p. 494

- ^ Roberto Muñoz Bolaños, "Por Dios, por la Patria y el Rey marchemos sobre Madrid". El intento de sublevación carlista en la primavera de 1936, [in:] Daniel Macías Fernández, Fernando Puell de la Villa (eds.), David contra Goliat: guerra y asimetría en la Edad Contemporánea, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788461705504, p. 153

- ^ this is the opinion repeated in numerous works, compare González Calleja 1991 or Blinkhorn 2008. However, a massive monographic study on requeté effort during the civil war does not mention Rada when discussing the militia buildup, compare Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936–1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709758, pp. 79-128

- ^ González Calleja 2011, p. 373, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 224

- ^ some scholars note that in mid-1936 the total number of Requeté volunteer was not much more than those in Falange's Primera Linea, but that they were definitely better armed and trained; as the result, no other militia was even close compared to military performance and potential of Requeté, González Calleja 2011, p. 373

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 224. In June 1936 the Requeté organisation included two colonels, capable of commanding units comparable to a regiment, Rada and Utrilla, Antonio Lizarza Iribarren, Memorias de la conspiración. Cómo se preparó en Navarra la Cruzada. 1931–1936, Pamplona 1953, pp. 66, 83, Arrarás 1965, p. 494

- ^ Robert Vallverdú i Martí, El carlisme català durant la Segona República Espanyola 1931–1936, Barcelona 2008, ISBN 9788478260805, p. 270

- ^ Pablo Larraz Andía, Víctor Sierra-Sesumaga, Requetés: de las trincheras al olvido, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788499700465, p.666

- ^ La Voz 25.01.36, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 27.01.36, available here. According to scholars, Rada’s personal influence was greatest in the Almeria comarca of Río Nacimiento, Quirosa-Cheyrouze 1994, p. 95

- ^ González Calleja 1991, p. 74

- ^ Muñoz Bolaños 2014, p. 12

- ^ despite his position in Requete and military competence as a battle-hardened Africanista who used to command regiment-type units, in the Carlist rising plans Rada was not listed as commander of any of the 5 columns, supposed to converge upon the capital, González Calleja 2011, pp. 376–377

- ^ Muñoz Bolaños 2014, p. 12

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 237, also Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 8487863523, p. 18

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 19

- ^ Atienza Peñarrocha 2012, pp. 926, 945

- ^ Óscar J. Rodríguez Barreira, Poder y actitudes sociales durante la postguerra en Almería (1939-1953), Almeria 2007, ISBN 9788482408460, p. 222

- ^ for some details, including co-ordination with the Carlist provinvcial leader Juan Banqueri Salazar, see the chapter Tradicionalismo de Almeria, [in:] Joaquin Delgado, Alcazaba de Almeria, Madrid 1965, pp. 173-174. One author claims that as the coup in Almería failed, requeté engagement produced “una auténtica hecatombe en las filas tradicionalistas” Rodríguez López 2005, p. 72

- ^ Javier Ugarte Tellería, La nueva Covadonga insurgente: orígenes sociales y culturales de la sublevación de 1936 en Navarra y el País Vasco, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788470305313, pp. 103, 271, 283, 291

- ^ Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesumaga 2011, p. 466

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 227

- ^ compare “Shortly after reading Sanjurjo’s reply, the Carlist leader [Fal Conde] entered into a heated argument with the Inspector-General of the Requeté, retired Lieutenant-Colonel Ricardo Rada, who was eager to join the rebellion. Fal Conde skilfully cut short a sterile discussion by claiming that he could not take a definite decision without consulting first with the Carlist regent to the throne, Prince Javier de Borbón-Parma. Rada’s explosive reaction was to be expected: he was an Africanista who had served in the Foreign Legion during the Rif campaign”, Rúben Emanuel Leitão Prazeres Serém, Conspiracy, coup d’état and civil war in Seville (1936-1939): History and myth in Francoist Spain [PhD thesis London School of Economics], London 2012, p. 36

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 249

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesumaga 2011, p. 830

- ^ Aróstegui 2013, p. 356

- ^ Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesumaga 2011, p. 930

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ from Tabor de Regulares de Sidi-Ifni, Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ during the Battle of Jarama Rada commanded one of 6 brigades of División Reforzada de Madrid, led by general Yoldi, and in some works he is listed among key commanders engaged in the battle, compare Lucas Molina Franco, Pablo Sagarra, Óscar González, Grandes batallas de la Guerra Civil española 1936-1939: Los combates que marcaron el desarrollo del conflicto, Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788490606506, p. 122. See also his detailed biography, which lists his command during the engagements at Cabeza Fuerte, La Maranosa, Vertice Coberteras, and Pingarron, Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ the section was headed by delegado nacional de requeté, Zamanillo. Rada as inspector general headed operations; the sub-section of intendencia was headed Adolfo Gómez Sanz, and the sub-sections of armaments by Javier Martínez de Morentín, Ricardo Ollaquindia, La Oficina de Prensa y Propaganda Carlista de Pamplona al comienzo de la guerra de 1936, [in:] Principe de Viana 56/2-5 (1995), pp. 486, 501

- ^ following death of Alfonso Carlos Rada sent a telegram to the regent with “mi incondicional adhesion junto con testimonio pesame”, Correspondencia, [in:] Pares service available here, p. 21

- ^ Milicia was headed by general Monasterio, Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714, p. 46

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 292

- ^ among Ricardo Oreja (sanidad section), Julio Muñoz Aguilar (press and propaganda section), Juan Echandi Indart (HQ secretary), and Jesús Elizalde (asesor requeté), Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 133. Other authors when naming highly positioned Carlists in FET list Rodezno, Florida, Mazon and Arellano (members of Junta Política), Gaiztarro, Llopart, Oreja and Urraca (heading section of hacienda, transportes, sanidad and frentes/hospitales respectively), Echandi Indart (secretario de despacho), Rada (subjefe de milicia), Eladio Esparza (vicepresidente del consejo). Provincial FET jefes were Carcer (Valencia), Oriol (Bizacay), Muñoz Aguilar (Gipuzkoa), Echave Sustaeta (Alava), Herrera Tejada (Logroño) and Garzón (Granada), Blinkhorn 2008, p. 292

- ^ some time in 1937 or 1938 Rada complained that all recruitment was channelled to Falange, “allí casi todas las autoridades están en frente de nosotros y a favor de Falange”, Josep Miralles Climent, La rebeldía carlista. Memoria de una represión silenciada: Enfrentamientos, marginación y persecución durante la primera mitad del régimen franquista (1936–1955), Madrid 2018, ISBN 9788416558711, p. 55

- ^ compare Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 72

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Caceres 22.07.37, available here

- ^ Rada commanded a local offensive near Navalvillar de Ibor in February 1938, Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ according to one scholar, in December 1937 as military governor of Cáceres Rada "ordered the execution" of 200 people whose names appeared in the papers found in the clothes of a local Communist leader on assumption of their taking part in the plot, Julián Casanova, The Spanish Republic and Civil War, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 9781139490573, p. 324. Slightly more details and a somewhat different perspective in Rafa Gonzalez, El franquismo criminal ensangrentó las navidades de 1937 en Cáceres, [in:] Mundo Obrero 23.12.20, available here

- ^ Montejurra I/9 (1965), p. 12

- ^ José Manuel Martínez Bande, La batalla de Pozoblanco y el cierre de la bolsa de Mérida, Madrid 1981, ISBN 9788471401953, p. 156

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ El Diario Palentino 13.05.38, available here

- ^ for details on Rada commanding in so-called Front del Pallars, northern section of the Aragon frontline, in May 1938, see very detailed and informative work of Manel Gimeno, Indrets d'una guerra: Cronologia del front del Pallars, Barcelona 2018, ISBN 9788416115259

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Rafael Casas de la Vega, El Requeté. La guerra de España, Madrid 1988, ISBN 9788440430786, p. 19, also Ramón Salas Larrazabal, Historia del Ejército popular de la República, Vol. II, Madrid 1973, p. 2013

- ^ José Manuel Martínez Bande, La batalla del Ebro, Madrid 1978, ISBN 9788471401670, p. 264

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ some scholars claim he exercised some political influence as well, e.g. when it comes to nomination of the mayor of Almeria in 1939, compare Oscar J. Rodríguez Barreiro, ¿Católicos, monárquicos, fascistas, militares? La lucha entre FET-JONS y el gobierno civil en Almería, [in:] Carlos Navajas Zubeldia (ed.), Actas de IV Simposio de Historia Actual, Logroño 2004, ISBN 8495747774, p. 689

- ^ El Progreso 01.09.39, available here

- ^ Hoja Oficial de la Provincia de Barcelona 27.05.40, available here

- ^ on April 21, 1939, calle Concepcion Arenal in Almeria was renamed to honor Rada. The name has been dropped in the post-Francoist era. The 2022 press article which discussed the fate of the street referred to Rada as "uno de los cabecillas del Alzamiento del 18 de julio de 1936", Eduardo de Vicente, La calle de los cuatro nombres, [in:] La Voz de Almeria 23.03.22, available here. On May 12, 1939, he was nominated Hijo Adoptivo by the self-government of Navarre; the decision was reversed in 2015, Ricardo Rada Peral, primero en desembarcar en Alhucemas y Combatiente en la Cruzada, [in:] Fundacion Francisco Franco website 18.02.15, available here. A street has been named after Rada also in Fiñana

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ ABC 28.01.40

- ^ however, during World War Two he reportedly tended to favor the Allies over the Axis, Jose Maria Verdejo Lucas, Ricardo Rada Peral, [in:] Diccionario biografico de Almeria online, available here

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Guillermo Portilla Contreras, El derecho penal bajo la dictadura franquista: Bases ideológicas y protagonistas, Madrid 2022, ISBN 9788411221399 p. 315

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ ABC 03.10.43

- ^ Diario de Burgos 21.06.45, available here

- ^ ABC 01.11.46

- ^ Brocos Fernández 2008

- ^ Rodríguez López 2005, p. 159

- ^ on Jan 21, 1941, Manuel Senante and Jose-Maria Lamamie de Clairac were returning by car from a meeting with Rada. The car was involved in a very serious road accident, with 5 fatal casualties. However, the key concern of the Carlists involved was that before Guardia Civil arrives, a set of documents they carried be put into a safe place, Apuntes y documentos para la historia del tradicionalismo español, vols. 1-3, Madrid 1979, ISBN 8430004432, p. 95

- ^ Rada had also other problems with security. He was suspected of having irregularly gained possession of paintings of a painter José María López Mezquita, and on Jan 1, 1940 his house by raided by agents of the services, with some clash ensuing, for details see Visitas realizadas por los agentes al domicilio de Ricardo Rada Peral para recuperar un cuadro del pintor José María López Mezquita, [in:] Instituto de Cultura y Deporte service, available here

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 224

- ^ Miralles Climent 2018, p. 98

- ^ Joan Maria Thomàs, Franquistas contra franquistas: Luchas por el poder en la cúpula del régimen de Franco, Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788499926346, p. 88

- ^ compare Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 9788431315641; Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009; Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939-1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015; Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965-1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015

Further reading[edit]

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294,

- José Martín Brocos Fernández, In memoriam Teniente General Ricardo de Rada y Peral. Primer General Jefe de la Acorazada Brunete, [in:] Arbil 116 (2008)

External links[edit]

- biography by Brocos Fernández

- photos from official Rada's funeral at Archivo Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid

- Rada's account on conspiracy in Spanish national archive

- Rada on Basque encyclopedia online

- Rada on Real Academia de Historia website

- former Rada's estate near Finana on Google Maps

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda