Robert Ballagh

Robert Ballagh | |

|---|---|

Ballagh in 2014 | |

| Born | 22 September 1943 Dublin, Ireland |

| Education | Bolton Street College of Technology |

| Known for | Painting, design |

| Notable work | More than 70 Irish postage stamps, "Series C" Irish banknotes |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Carabini

(m. 1967; died 2011) |

| Children | 2, including Rachel |

| Awards | Aosdána membership[1] |

Robert Ballagh (/bæləx/; born 22 September 1943) is an Irish artist, painter and designer. Born in suburban Dublin,[2][3] Ballagh's initial painting style was strongly influenced by pop art. He is also known for his hyperrealistic renderings of Irish literary, historical and establishment figures,[4] or designing more than 70 Irish postage stamps and a series of banknotes, and for work on theatrical sets, including for works by Samuel Beckett and Oscar Wilde, and for Riverdance in multiple locations. Ballagh's work has been exhibited at many solo and group shows since 1967, in Dublin, Cork, Brussels, Moscow, Sofia, Florence, Lund and others, as well as touring in Ireland and the US. His work is held in a range of museum and gallery collections. He was chosen to represent Ireland at the 1969 Biennale de Paris.

A lifelong resident of Dublin, he was made a member of Ireland's academy of artists, Aosdána He became the founding chairperson of the Irish Visual Artists Rights Organisation. He has received a number of awards, including an honorary doctorate from UCD. He has published a book of photography of Dublin, and a volume of memoirs.

Early life and education[edit]

Born 22 September 1943,[5]: 5 Ballagh grew on Elgin Road in Ballsbridge, the only child of a Catholic mother, Nancy (maiden name Bennett), and a Presbyterian father, Bobbie (also Robert), who converted to Catholicism.[6] Both parents had played sport for Ireland, his mother hockey, his father tennis and cricket.[3][5]: 96 His father was the manager of the shirt department of a drapery shop on South William Street; his mother, who came from a comfortable middle-class background, stopped working when she married. Robert attended a private primary school, Miss Meredith's School for Young Ladies on Pembroke Road,[5]: 5 and then the fee-paying St Michael's College[7] and Blackrock College.[3] He became an atheist during his secondary education.[7] His parents were members of the Royal Dublin Society, one of Ireland's most active learned societies, and he spent time in its library and looking at its collection of art books, while also collecting American comics and frequenting the local cinema, not just to watch films but also observing for hours the sign painter at work.[5]: 6 He began to work on art seriously in 1959, and some of his early works, including a self-portrait, were later exhibited as part of a retrospective show at the Gorry Gallery.[8]: 9, 25–30

After passing his Leaving Certificate, Ballagh attended Bolton Street College of Technology for three years, studying architecture, including with Robin Walker, who had worked with Le Corbusier; he concluded that this was not the career for him, and that it conflicted with his musical career ambitions, while his tutors found him excessively interested in designs beyond his briefs.[9]: 10

Career[edit]

Before turning to art as a profession, Ballagh was a professional musician for about three years, initially with the showband Concord, then, on a full-time basis, as bass guitarist with The Chessmen, managed by Noel Pearson.[3][5]: 7 Having toured Ireland and England extensively with the latter band, reaching a weekly income of 100 pounds, he concluded that a career in music, especially with a lot of time on the road, was not for him, sold his guitar, to rising musician Phil Lynott[10] and did not play music again.[11]

Painting and other plastic arts[edit]

Ballagh worked in both Dublin and for a few months, London, as a draughtsman, a postman and a designer. Having decided to return to Ireland, he started on a dedicated artistic career after he met an artist friend, Micheal Farrell,[a] freshly returned from the New York art scene, in a pub, and Farrell recruited him for 5 pounds a week to assist with a large mural commission. The piece, for the National Bank branch on Suffolk Street (part of Bank of Ireland),[5]: 7 was painted at Ardmore Studios due to its massive scale.[10] Two early pieces of three-dimensional art, an erotic torso and a pinball machine, were selected to appear at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art in 1967, and Ballagh has appeared in a range of group exhibitions since. Around the same time, Ireland's Arts Council purchased an acrylic of a razor blade on canvas, inspired by a theory of critic Clement Greenberg.[5]: 7 Largely self-taught, his early work took inspiration from the pop art movement, and he worked on two early series of paintings, the Package series and Map series, the latter using a mix of acrylic and day-glo paints in inkblots.[8]: 10 He next turned to political themes, notably connected to Northern Ireland[10] but also with elements inspired by the Civil Rights movement in the US and the reaction to the Vietnam War.[8]: 10 He started to combine elements of social realism with US advertising forms after reading Che Guevara's essay Man and Socialism in Cuba.[5]: 7 He also produced three early works which have remained critically recognised ever since, inspired by Liberty at the Barricades (Delacroix), Third of May (Goya) and Rape of the Sabines (David).[5]: 8 In 1972, he commemorated the victims of Bloody Sunday in Derry with an installation at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art at the Project Arts Centre in Dublin; it consisted of thirteen rough figures in sand on the floor, sprinkled with (animal) blood, recorded as a series of photoprints.[8]: 12

He was selected to represent Ireland at the 1969 Biennale de Paris,[4] and his work has been shown in solo exhibitions from that year onwards.[10] He was commissioned by his former tutor, Robin Walker, to produce abstract designs for screens in the new restaurant building of University College Dublin.[12]

Ballagh started to work on portraiture with Irish contemporary art collector Gordon Lambert in 1971. As he was at the time still not fully content with his skills in painting faces and hands, he merged his own canvas with a silkscreen headshot of Lambert, over which he worked with sepia ink, and he added the hands in detached three-dimensional representations, which sculptor Brian King made for him from castings of Ballagh's own hands.[5]: 8 Over the following years, he painted a series of people looking at contemporary paintings, which proved very popular, with some international exhibitions selling out.[5]: 8 Using the same concept, in his first major public commission, for the Five-Star supermarket chain's new shop in Clonmel, he painted a large-scale (c. 80 foot) mural on 18 panels. He used formica, and included himself, his wife and his daughter in the mural, entitled People and a Frank Stella.[13] He also, drawing on scenes from The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by locally-born Lawrence Sterne, painted a series of panels for a local restaurant. Other work included a series of six paintings and a silkscreen print linked to Flann O'Brien's The Third Policeman.[5]: 8–9

He later painted fellow artist Louis le Brocquy, writers J.P. Donleavy (2006), James Joyce (2011, commissioned by UCD), Sheridan Le Fanu, Oscar Wilde, Brendan Behan and Samuel Beckett, as well as poet Francis Ledwidge, singer Bernadette Greevy, politician Carmencita Hederman[5]: 33 and a rendering of Fidel Castro.[10] The Ledwidge, commissioned by the Inchicore Ledwidge Society, is a triptych, with the poet primarily on the central panel, but his arms crossing to the outer panels, which feature a scene from his home village of Slane and a World War I scene.[14] He had earlier painted Joyce in a scene on O'Connell Street, Dublin's main street, with himself alongside.[8]: 13 Some years after buying Ballagh's The History Lesson, the scientist James D Watson visited Ballagh in Dublin to discuss a portrait commission, and the Ballaghs visited the Watsons at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, with Ballagh commenting on the new insights into the world of science he gained from the visit.[5]: 12–14 Ballagh worked on a portrait of Watson over an extended period; it hangs in the Genetics Institute of Trinity College Dublin. At Watson's request, Ballagh painted Watson's colleague Francis Crick for a major institution in London, and at the unveiling was one of just two people to meet the Queen, who commented that the portrait was "interesting".[15] Other commissions included Dublin City University purchasing a portrait of former Minister for Education Mary O'Rourke.[5]: 38 By 2010, Ballagh had painted 91 non-family portraits, featuring 82 men and 9 women.[5]: 33

Works of self-portraiture and paintings of his family have also been created over time. One of these, Inside Number 3, described by Eamonn Ceannt as moving on from "the conventional architectural perspective of his previous paintings" and marking "a turning round of his own approach to painting", featured his wife as a nude figure on a spiral staircase in their home.[16] That work was preceded by No. 3, with his family portrayed conventionally outside their house, and was followed by Upstairs No. 3. This was a second intimate portrait, with a mostly nude Ballagh ascending a spiral stairway, seen from the perspective of his wife on their bed with a book of Japanese erotica; he commented that he really felt that Inside Number 3 called for a response, and that the needed male nude had to be himself.[17] Later still he painted Inside No. 3 After Modernization (with multiple types of painting included in the background), Upstairs No. 4, and others. In a very different setting, he also painted his family on an extended 1978 holiday near Malaga, in Winter in Ronda (1979).[5]: 9, 167 He also used himself and family members as models for generic characters, and, for example, painted two pictures of his daughter in homage to Marilyn Monroe, Rachel as Marilyn I and II.[8]: 51

After many years, and one painting looking out to an exterior scene in the mid-1980s, Ballagh started to paint landscape work seriously in the late 1990s, and his 2002 exhibition, Tir is Teanga / Land and Language consisted of 10 landscapes, albeit not of specific places, but typical of some Irish scenes.[8]: 18–19 Another commission was to paint the Fastnet Lighthouse for the Commissioners of Irish Lights.[17]

Ballagh has served as a judge for a number of artistic competitions, including one for murals in West Belfast.[5]: 22–23 He has also led community arts work in both Dublin and Belfast,[5]: 34–35 and taught art in prisons.[5]: 53–54 One community art project in Dublin, to make a massive mural placed in front of the Custom House, was the subject of an RTE television documentary.[5]: 34–35

Studio[edit]

For many years, Ballagh rented an attic-level studio on Parliament Street in Dublin, overlooking City Hall; this studio had previously been leased by other artists, such as Patrick Collins. After he lost the lease on that in the mid-1980s (it was repurposed as part of the development of Temple Bar and eventually hosted the Walt Disney Company's Irish office), he worked from home. Finding home working difficult with two growing children, in the early 1990s he used an inheritance to buy a house and former piggery on Arbour Hill, less than 10 minutes walk from his home. He renovated the building, and it now hosts his studio and a small flat.[18] The artist has mentioned that he sometimes works slowly and in great detail; in 1982, for example, he produced just two paintings, spending about 6 months on each.[19] His work has sold well at auction.[20][5]: 11 One painting, My Studio 1969, sold for 96,000 euro in 2004.[5]: 11

Postage stamp and banknote design[edit]

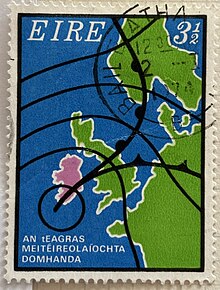

Ballagh has designed over 70 Irish postage stamps, as well as a series of Irish banknotes, "Series C", the last series before the introduction of the euro.[21][22] Ballagh's first postage stamp design was released on 4 September 1973. It commemorated the centenary of the World Meteorological Organization and depicted a weather map of northwestern Europe. His portrayal of Ireland did not show the border with Northern Ireland, provoking the unionist politician Ian Paisley to demand in the British House of Commons that the British government should make a formal objection, even though no other international borders were shown either.[23][24] Later design contracts included the centenaries of the Universal Postal Union and the first telephone transmission, the golden jubilee of Ireland's national electricity utility, the Electricity Supply Board, the centenaries of the births of Patrick Pearse and Éamon de Valera and commemorations of various other Irish statesmen, issues related to Scouting, Guiding and the Boys' Brigade, Irish festivals, the Irish lighthouse authority and one of Ireland's annual "love stamps".[25] One stamp design was rejected by the government, after stamps had already been printed, possibly due to interference by Taoiseach Charlie Haughey; the stamps and plates were destroyed.[5]: 41 A version of the stamp was eventually released more than 15 years later.[5]: 68 On another occasion, in 1994, he was commissioned to produce stamps commemorating five Irish Nobel Prize winners; four were released but the fifth was cancelled when An Post belatedly realised that the subject, physicist Ernest Walton, was still alive.[5]: 67–68

Theatre set and other design work[edit]

Ballagh has worked on set design for both travelling shows and plays and events based in Ireland. He was approached to try this type of work by the director of Dublin's Gate Theatre, Michael Colgan. Among the theatrical sets he has designed are ones for Riverdance on international tour,[26] and later in Dublin too,[5]: 73–76 the one-man show I'll Go On (Gate Theatre (1985), based on Samuel Beckett's novels,[27] Beckett's Endgame (1991), Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest (1987) and Salomé (1998),[21] Chekhov's Three Sisters, Hamlet,[b] and Michael Harding's Misogynist.[5]: 59–60 He also did set work for the Dublin Theatre Festival.[8]: 17

For Riverdance, impresario Moya Doherty, co-creator of the show, asked Ballagh to use a hand-made approach, and he produced around 50 small images, which were then projected to form backdrops. A further complication is that while Ballagh started by designing for the London part of the Riverdance tour, he later had to rework his designs to accommodate different venues, with varying technical capabilities, such as projection only from the front, from front and back, or from different directions along with moving objects crossing them.[8]: 17

Ballagh was also designer for the opening ceremonies for two major sporting events hosted in Ireland, the 2003 Special Olympics World Summer Games and the 2006 Ryder Cup.[28] Many years later, he was commissioned to produce a tableau vivant for a promotional event at the Royal Hibernian Academy's Gallagher Gallery, a living artwork inspired by a famous painting – he chose to work with The Girl with a Pearl Earring.[5]: 67

In other domains of work, he designed a masthead for the Irish Examiner,[17] and a cover for a musical single.[29]

Exhibitions[edit]

Solo exhibitions[edit]

Ballagh has had solo shows in Dublin on several occasions, as well as in Brussels, Paris, Lund in Sweden, Warsaw, Moscow and Sofia.[5]: 24 His first exhibition was in 1969, at the Little Theatre in the original Brown Thomas shop on Grafton Street; it was opened by Conor Cruise O'Brien, who described him as "an exceptionally gifted, thoughtful young artist."[30][31][5]: 8

Later shows of original work in Ireland included a 1971 case at the Cork Art Society,[32] and in years including 1970,[12] 1971, 1972 and 1983, exhibitions at the gallery of his dealer, David Hendricks, in Dublin.[5]: 8–9 After Hendricks died and his gallery closed, Ballagh decided to work without a Dublin dealer and primary gallery, and his next exhibition of new work in Dublin only came after a 26-year gap, in 2009, with "Tir is Teanga" ("Land and Language"). This show consisted of paintings with natural materials such as stones, sand, and metals, added, and with Irish language texts.[33] There was a show of some of his 1970s material at the Orchard Gallery in Derry, organised by Patrick T Murphy and Declan McGonagle.[5]: 118

In 1982, Ballagh was invited to put on a "mid-term retrospective" show in Lund in southern Sweden, which proceeded in 1983.[12] He exhibited at West Cork Arts in 1986.[9]: 10

In 1989, he was invited to put on a major retrospective at the Gallery of the Central House of Artists (of the Soviet Union) in Moscow (later the New Tretyakov Gallery),[34] only the second Irish person and third Westerner to be so invited, after Francis Bacon and Robert Rauschenberg.[5]: 42–43 He afterwards gifted samples of his work to the USSR's ambassador to Ireland and to Mikhail Gorbachev.[11]

Ballagh had his first major retrospective show in Ireland, Robert Ballagh – The Complete Works, in the top-floor exhibition space at Arnotts department store on Henry Street, in February 1992,[5]: 58–59 launched by Hugh Leonard.[35] The exhibition included 100 examples of his work, consisting of paintings, including portraits, designs for stamps, book illustrations and theatrical sets, limited edition books, and photography.[36] The show was centred on a selection of 33 paintings from his 25-year career to date,[37] 26 commissioned illustrations and limited edition prints, books for Gallery Press and Black Cat Press, 12 photographs, 12 stamps, models and photographs from theatrical work, and three stationery designs. The exhibition catalogue included three essays on his painting, and one each on his limited edition prints, stamp design work, photo-essay book and stage design.[38]

Further retrospectives followed, the next, and most significant, being at the Gallagher Gallery of the Royal Hibernian Academy, with a gallery-within-a-gallery format,[5]: 118 – with a display of his stamps at the General Post Office in parallel. The retrospective was nearly cancelled due to lack of funding for the elaborate gallery setup but rescued by sponsorship by Dermot Desmond.[5]: 128 There was also a show at the Gorry Gallery (Works from the Studio, 1959-2006).[8]

An exhibition of seven portraits of political and cultural people of note, and seven self-portraits, Seven, was held at Cork's Crawford Art Gallery in 2013,[39] and a selection of works related to the 1916 Easter Rising were exhibited at the Kevin Kavanagh Gallery in 2016.[40]

Major group exhibitions[edit]

Having had works displayed at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA) in 1967, Ballagh was invited to show at the 1968 edition. He was also invited to the 1969 IELA, which had to move from the College of Art on Merrion Square to venues in Cork and Belfast. Having submitted a painting for consideration in 1969, after discussion with other artists' wives, his wife was also invited. After an outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland, 9 artists, including the Ballaghs, refused to allow their works to be sent there; they were instead displayed in an alternative exhibition, Art and Conscience, at 43 Kildare Street (and in the end, the exhibition never did go to Belfast). Sometime after, he exhibited three works commenting on the Northern Irish situation at Celtic Triangle, a joint exhibition of the Arts Councils of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.[12]

Having featured at the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, and been inspired by earlier editions of the exhibition, Ballagh was invited to show at Rosc in 1980. He was also invited, in 1987, to participate in a peace forum and associated major exhibition in the Soviet Union, at the Cosmos Hotel in northeastern Moscow, a rare invitation for an Irish artist. At the event he breakfasted with Gregory Peck, lunched with Yoko Ono and chaired a panel consisting of Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal and Graham Greene.[5]: 28

Ballagh has been included in exhibitions in Florence and Tokyo, and has also had work on tour in the US in the period 1985–1987, as part of the "Divisions, Crossroads, Turns of Mind: Some New Irish Art" exhibition.[41] One of his works also featured in 30 years, artists, places, a travelling exhibition of work acquired by Irish local authorities.[42]

Recognition and leadership roles[edit]

Ballagh received the Carroll Prize at IELA 1969,[9]: 10–11 and the Alice Berger Hammerschlag Award, an all-island award for practitioners of the "plastic arts", at the Arts Council of Northern Ireland in 1971.[43]

He was a founding member of Ireland's national academy or "affiliation" of artists, Aosdána, in 1981, and its first chairperson (the leader of its presiding body, the Toscaireacht).[1][28] He ceased active participation in the body in the early 1990s, after what he felt was undue pressure to declare his personal views in a debate about censorship.;[5]: 65–66 he eventually resigned membership, one of only four artists to do so in the more than 40 years of the academy's existence. He was also made a fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science, one of only two Irish fellows.[28][5]: 68 He was awarded an honorary doctorate of letters in 2013 by University College Dublin.[16] In 2016, he received a Lord Mayor's Award in Dublin.[44]

Two of his works won the Douglas Hyde Gold Medal at editions of the Oireachtas Exhibition.[5]: 11–12 Another piece, 'Northern Ireland, The 1,500th Victim (1976) was selected as one of the "Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks" series of the Royal Irish Academy.[45]

Ballagh was the first chairperson of the Artists Association of Ireland,[46] and the founding chairperson of the Irish Visual Artists Rights Organisation.[39]

Collections[edit]

Ballagh's paintings are held in several public collections of Irish painting including those of the National Gallery of Ireland, the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin, the Ulster Museum, the Irish Museum of Modern Art, the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork, along with the collections of Trinity College Dublin, the Musée des beaux-arts de La Chaux-de-Fonds and Nuremberg's Albrecht Dürer House.[27] Reproductions of three of his works are among the most-borrowed items in the Trinity College Dublin collection.[28]

Approach and critical commentary[edit]

Ballagh has said of his work: "You hope that your paintings will transcend their time but they must be of their time as well" and of a potential inspiration: "... the master of the 20th century, Picasso. He did so many different things, had so many styles and approaches. That seems to me the way, the model."[8]

Some commentators have made observations about what might motivate Ballagh, with Declan Kiberd saying: "Robert Ballagh is the major current example of the Irish artist as activist. He has espoused the causes of socialism, republicanism, workers' rights and nuclear disarmament ... Yet his own painting is free of all propaganda."[9]: 10 and Brian O'Doherty: "his is not so much political art as art made by an intensely political person."[9]: 10 Roderic Knowles noted his move from "abstraction to figuration" and "his social commitment, which shows itself in his humour and wit, parody and pastiche and social comment, and his quite shameless literary and artistic allusions", while Cyril Barrett referenced his changing approach, with "the figure first as a silhouette or 'cut-out', then as a painted figure (as in his pastiches of Goya, Delacroix, Poussin or Ingres)".[47]

The former director of the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) once characterised Ballagh as more of an illustrator than an artist; nonetheless, IMMA holds a range of his works. Dorothy Walker's Modern Art in Ireland made almost no mention of Ballagh and his body of work.[5]: 59

Political and cultural interests[edit]

Artists' representation and rights[edit]

Ballagh has long campaigned for artists' rights, notably in regard to resale, and for better funding for the arts. He pursued the question of resale rights, assured by EU law but late to be implemented in Ireland, threatening, and later pursuing, legal action; the right was eventually established.[48] He has pursued this aim individually and in his roles in the Artists Association of Ireland,[46] and the Irish Visual Artists Rights Organisation (IVARO).[39] He also worked with the UNESCO-associated body of artists, the International Association of Art, to the executive committee of which he was elected, and on which he served as treasurer for three years; this work involved considerable travel and his work on the representational bodies made him so busy in 1987 that he painted nothing at all.[5]: 31 Ballagh has commented that Ireland's funding of the arts is poor by EU and OECD standards.[49]

Politics and republicanism[edit]

In an interview with The Irish Times, Ballagh ascribes his "political awakening" to hearing news of civil rights protestors in Derry, Northern Ireland, being attacked by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in 1968.[6] In 1988 he contributed to the West Belfast Féile an Phobail arts festival. In 1989 he was a founder member of the Irish National Congress and chaired it for 10 years.[50][51] In 1991, he co-ordinated the 75th-anniversary commemoration of the 1916 Easter Rising, during which he claimed he had been harassed by the Special Branch of the Garda Síochána.[52] He has commented that the Easter Rising was "led by poets, actors, writers, musicians, social reformers, Irish language activists – a truly remarkable gathering of people ..."[8]: 13

He is the president of the Ireland Institute for Historical and Cultural Studies,[2] which promotes studies of republicanism in an international context. It is based at the Pearse Centre at 27 Pearse Street, Dublin, once home to Pádraig Pearse.[53][54]

Ballagh was on the committee of a major group campaigning for a "No" vote in Ireland's referendum on the Lisbon Treaty.[5]: 17

2011 presidential run rumours[edit]

In July 2011 it was reported that he might consider running for the 2011 Irish Presidential election with the backing of Sinn Féin and the United Left Alliance.[55] A Sinn Féin source stated there had been "very informal discussions" and that Ballagh's nomination was "a possibility" but "very loose at this stage".[56] On 25 July, Ballagh ruled out running in the election, saying that he had never considered being a candidate; his discussions with the parties had been about the election "in general" and he had no ambitions to run for political office.[57]

Palestine[edit]

Also in July 2011, Ballagh broke ranks with his colleagues involved with the travelling production of Riverdance over their decision to perform in Israel. He is an active member of the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, which has asked that artists and academics participate in boycotts of Israeli businesses and cultural institutions.[58]

Closure of Irish galleries and museums[edit]

In July 2012, Ballagh said he was "ashamed and profoundly depressed" at the en masse closure of Irish galleries and museums. He cited an example of some Americans and Canadians on holiday in Ireland. "They described most of the National Gallery as being closed along with several rooms in the Hugh Lane Gallery. I'm glad they didn't bother going out to the Museum of Modern Art in Kilmainham because that's closed too. At the point I met them, they were returning from Galway where they had found the Nora Barnacle Museum closed too." Ballagh condemned the hypocrisy of political leaders, saying: "I know arts funding is not a big issue for people struggling to put food on the table but we are talking about the soul of the nation."[59]

Publications and appearances[edit]

Ballagh published a book of Dublin photography, taken over a year on a Rolleiflex camera, accompanied by quotations from James Joyce, in the 1980s. The book focused on less-well-known or disappearing sights of the city.[8]: 13 [60] A Robert Ballagh Monograph was published in a limited edition in 2010, with a set of giclee prints.[5]: 10 He published an academic paper, "Who fears to speak of the Republic?" in the journal Études irlandaises.[61] He released an autobiographical volume, A Reluctant Memoir, in 2018; it is not written as a chronological summary of his life but consists of a range of short pieces around major events.[6][62]

Documentaries were produced about Ballagh, by the BBC (directed by Paul Muldoon), and in Irish, by Igloo Films, in 2001 (directed by Anthony Byrne).[63]: end cover In 2019, he appeared as a contestant on RTÉ's Celebrity Home of the Year, where his house finished in second place.[64] He was the guest speaker at the 2012 Ledwidge Day commemoration at Islandbridge.[65]

Personal life[edit]

Ballagh met his future wife Betty (Elizabeth Carabini, from a Dublin family of Italian descent) in 1965, when she was 16 and he was playing a musical gig.[16] They had two children, Rachel, born 1968, who also became an artist, and Robert Bruce, born late 1974 or early 1975.[12] During his early years as a self-employed artist, Ballagh sometimes signed on for unemployment benefits while seeking paid work;[8]: 53 even much later he remarked on the instability of artistic income, noting that he earned no money at all in the first half of 2019, for example.[66]

The couple originally purchased one artisan's dwelling,[c] then a row of them which they merged into a single architect-designed dwelling, with Ballagh participating in the design. The finished building, Ballagh House, was later profiled in Architecture Ireland, the official journal of architects in Ireland,[67] and featured on a TV show.[64]

Betty Ballagh fell and received a brain injury in 1986, falling into a coma and requiring an operation to remove a clot; it took her years to fully recover.[5]: 26–28 Robert's parents died within three months of each other in 1990.[5]: 48–50 Betty died at St Joseph's Hospital, Raheny, in 2011, after a couple of months awaiting treatment for diverticulitis.[1][6] He later sued on grounds of negligence by the Health Service Executive and members of its staff, and received a settlement.[6]

By the mid-2000s, he had two grandchildren.[5]: 71 He had chemotherapy treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and recovered fully; he subsequently received a diagnosis of type II diabetes.[17] As of 2021, Ballagh still lived in Broadstone and kept his studio in nearby Arbour Hill.[18]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Robert Ballagh". Aosdána. 15 October 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ a b "RHA Exhibitions: Robert Ballagh 14 September – 22 October 2006". Royal Hibernian Academy. 15 October 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d "'I'm popular with the public yet ignored by the art establishment'". The Irish Times. 19 June 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Irish Art & Artists: past & present". Whytes Irish Art Auctioneers and Valuers. Archived from the original on 24 August 2002. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av Carty, Ciaran (2010). Robert Ballagh: Citizen Artist (1st ed.). Howth, County Dublin: Zeus Medea. ISBN 978-0-9525376-1-8.

- ^ a b c d e Mick Heaney (15 September 2018). "Robert Ballagh: 'You have to fight for your rights'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ a b Healy, Yvonne. "Robert Ballagh's school days set him against denominational education and marked his start in rock 'n' roll". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Vann, Philip (2006). Mathews, Damien (ed.). Robert Ballagh: Works from the Studio, 1959-2006. The Gorry Gallery in association with Damien Mathews Fine Art.

- ^ a b c d e O'Byrne, Robert, ed. (5 January 2024). Dictionary of Living Irish Artists. Dublin: Plurabelle. ISBN 9780956301109.

- ^ a b c d e "Robert Ballagh and Pop Art as a Medium for Politics". University Times (TCD). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Rennaisance man remains in North Dublin". The Irish Independent. 27 September 2001. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Ballagh, Robert. A Reluctant Memoir. Dublin: Head of Zeus.

- ^ Out of cold storage – Ballagh's mural back on display after 27 years

- ^ An Exhibition of 18th to 21st Century Irish Paintings. Dublin: The Gorry Gallery. 2014. p. 34.

- ^ Marian Finucane interview

- ^ a b c Ceannt, Eamonn. "Honorary Conferring – Robert Ballagh". University College Dublin. UCD President's Office. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d O'Byrne, Ellie (19 October 2018). "'Jesus, did I paint them?'; Robert Ballagh reacts to the nude portraits of him and his wife". The Irish Examiner.

- ^ a b Costello, Rose (6 November 2023). "Where I work: an artist's messy haven in Dublin 7". The Times (of London). ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh: upstairs, downstairs". Magill. 31 March 1983. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Flegg, Eleanor (18 November 2016). "Treasures: Looking out for a Ballagh". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Robert Ballagh – Irish Pop Artist, Designer, Contemporary Painter. Biography, Paintings". Encyclopedia of Irish and World Art. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Fiona; Coates, Sam; Savage, Michael (15 October 2006). "Art: Robert Ballagh". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Ballagh, Robert (6 November 1994). "Making a mark with tiny paintings". The Tribune Magazine. Dublin: Sunday Tribune. p. 18.

- ^ Postage Stamps of Ireland: 70 years 1922 ~ 1992. Dublin: An Post. 1992. p. 50. ISBN 1-872228-13-5.

- ^ Postage Stamps of Ireland: 70 years (1922 – 1992). Dublin: An Post. 1992. ISBN 1-872228-13-5.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh – Set Designer". Riverdance. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Robert Ballagh". AskArt. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d van Embden, Mieke (2008). Trinity College Dublin Art Collections: Robert Ballagh. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh Prints". Irish Chamber Orchestra. 9 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ O'Connor, Kevin (16 July 1969). "Going Places (social column)". The Evening Herald. p. 9.

Dr. Conor Cruise O'Brien, T.D. ... the artist, Robert Ballagh ... Mr. Vincent Poklewski-Koziell, director, Brown Thomas

- ^ Mitchell, Adam (18 July 1969). "Theme is mass violence". The Irish Independent. p. 22.

Robert Ballagh, who will be Ireland's representative at the Paris Biennale, is concerned with mass violence and man's gradual subjection ... essentially pop art ... blacks and greys, lightened with ... red, blue and green.

- ^ Pyle, Hilary (21 November 1971). "Robert Ballagh's social commentary". The Sunday Independent. p. 22.

- ^ "First Ballagh Dublin show since 1983". RTE Entertainment. 30 January 2009.

- ^ Clines, Francis X. (10 June 1989). "It's a Long Way Away, But the Work Is Grand". The New York Times. p. 4.

- ^ Leonard, Hugh (16 February 1992). "More bricks than kicks (Leonard's log)". The Sunday Independent. pp. 3L.

... opening the Robert Ballagh exhibition at Arnotts ... The City Manager ... Frank Feeley ... The exhibition itself was a great success ... Le Tout Dublin was there, including Gay Byrne ...

- ^ Murphy, Catherine (6 February 1992). "Life's full circle for artist Bobby (Ad Lib column)". The Evening Herald. p. 16.

... one of our most famous artists ... first ever show of works in this country ... Nine years ago he helped set up and judge the National Portrait Awards ... (list of work types) ... Alan Stanford's ... production of Hamlet ... more than 200 guests

- ^ Ruane, Frances (19 February 1992). "Idea-based art – Robert Ballagh at Arnotts". The Irish Times. p. 10.

- ^ Arnotts presents... Robert Ballagh – The Complete Works. Dublin: Arnotts plc. 1992.

- ^ a b c "Robert Ballagh – Seven". Crawford Art Gallery. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh – Who fears to speak of the Republic". Kevin Kavanagh Gallery. 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Lippard, Lucy (1985). Divisions, Crossroads, Turns of Mind: Some New Irish Art. Madison, Wisconsin: Ireland America Arts Exchange (with the Williams College Museum of Art).

- ^ Ni Chonaill, Muireann (2015). 30 years, artists, places. The Association of Local Authority Arts Officers. ISBN 978-0-9931333-1-2.

- ^ Theo (28 June 1971). "Memorial award for plastic arts". The Belfast Newsletter. p. 5.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh among Lord Mayor's Awards winners". The Irish Times. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks: Robert Ballagh". 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Irish art collections (Robert Ballagh)". Solo Arte. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Knowles, Roderic, ed. (1982). "A directory of contemporary artists". Contemporary Irish Art: A Documentation. Dublin: Wolfhound Press. p. 216. ISBN 9780863270017.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Marc (22 February 2006). "Leading Irish painter Ballagh set to sue State over artists' royalties". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Fran Curry (interviewer), Robert Ballagh (interviewee) (2 July 2019). Robert Ballagh Artist Talk (E08). Clonmel Junction Arts Festival. Event occurs at 26:16.

- ^ "Tom Cooper to speak at Crossbarry event". Southern Star. 9 March 2019.

- ^ "Robert Ballagh". Troubles Archive.

- ^ "1916 and All That – A Personal Memoir". Ireland Institute. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ "27 Pearse Street". Dublin Civic Trust. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Forde, Neil (18 September 1997). "New group to 'promote understanding of Irish revolution' - Irish Institute for Historical and Cultural Studies set up". An Phoblacht. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Cullen, Paul (23 July 2011). "Ballagh may join Aras race with SF support". The Irish Times.

- ^ Sheehan, Fionnan (22 July 2011). "Left-wing parties back artist Ballagh for Aras". Irish Independent. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ McDonagh, Marese; Sheahan, Fionnan (26 July 2011). "Robert Ballagh rules out running for President after talks". Irish Independent. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ Riverdance sets off on Israel tour, Jewish Chronicle, 13 September 2011

- ^ Bryn Sisson, Laura (27 July 2012). "Artist Robert Ballagh slams political leaders over museum closures: Tourists seeking Irish art repeatedly turned away". Irish Central. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Ballagh, Robert (1989). Dublin. Dublin: Ward River Press.

- ^ Ballagh, Robert (30 November 2016). "Who fears to speak of the Republic?". Études irlandaises (41–2): 51–68. doi:10.4000/etudesirlandaises.4979. ISSN 0183-973X.

- ^ Kiberd, Declan. "A Reluctant Memoir review: Portrait of artist as critical traditionalist". The Irish Times. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ Robert Ballagh – Artist and designer. Royal Hibernian Academy. 2006.

- ^ a b "Inside Irish author John Boyne's 'Celebrity Home of the Year'". Irish Independent. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Society honours late poet Ledwidge". Drogheda Independent via independent.ie. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Sheridan, Colette (1 July 2019). "Iconic '70s Robert Ballagh mural back on display". The Irish Examiner. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ O'Toole, Shane (17 August 2003). "Temple of Room". The Sunday Times.