Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of National Defence of the Italian Social Republic | |

| In office September 23, 1943 – April 25, 1945 | |

| President | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Viceroy of Italian East Africa | |

| In office June 11, 1936 – December 21, 1937 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Prime Minister | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Pietro Badoglio |

| Succeeded by | Amedeo, Duke of Aosta |

| Governor-General of Italian Libya | |

| In office July 1, 1940 – March 25, 1941 | |

| Preceded by | Italo Balbo |

| Succeeded by | Italo Gariboldi |

| Governor of Italian Somaliland | |

| In office March 6, 1935 – May 9, 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Maurizio Rava |

| Succeeded by | Angelo De Ruben |

| Vice-Governor of Italian Cyrenaica | |

| In office March 17, 1930 – May 31, 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Domenico Siciliani |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 11, 1882 Filettino, Italy |

| Died | January 11, 1955 (aged 72) Rome, Italy |

| Resting place | Affile, Lazio, Italy |

| Political party | National Fascist Party (1924–1943) Republican Fascist Party (1943–1945) Italian Social Movement (1946–1955) |

| Spouse(s) |

Ines Chionetti (m. 1913–1955) |

| Children | A daughter |

| Alma mater | Military Academy of Modena |

| Profession | Military officer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1903–1945 |

| Rank | Marshal of Italy |

| Unit | Italian 10th Army |

| Battles/wars | Italo-Turkish War World War I Pacification of Libya Second Italo-Abyssinian War World War II |

Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli (Italian pronunciation: [roˈdɔlfo ɡratˈtsjaːni]; August 11, 1882 – January 11, 1955), was a prominent Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's Regio Esercito (Royal Army), primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during World War II. A dedicated fascist, he was a key figure in the Italian military during the reign of Victor Emmanuel III.

Graziani played an important role in the consolidation and expansion of Italy's empire during the 1920s and 1930s, first in Libya and then in Ethiopia. He became infamous among the other colonial powers for repressive measures that led to high loss of life among civilians. In February 1937, after an assassination attempt during a ceremony in Addis Ababa, Graziani authorized a period of brutal retribution now known as Yekatit 12. Shortly after Italy entered World War II he returned to Libya as the commander of troops in Italian North Africa but resigned after the 1940-41 British offensive routed his forces. Following the 25 Luglio coup in 1943, he was the only Marshal of Italy who remained loyal to Mussolini and was named the Minister of Defense of the Italian Social Republic, commanding its army and returning to active service against the Allies for the rest of the war.

Graziani was never prosecuted by the United Nations War Crimes Commission; he was included on its list of Italians eligible to be prosecuted for war crimes, but post-war Ethiopian attempts to bring him to trial were resisted by Italy and Britain. In 1948, an Italian court sentenced him to 19 years' imprisonment for collaboration with the Nazis, but he was released after serving only four months.

Rise to Prominence

Rodolfo Graziani was born in Filettino in the province of Frosinone.[1] In 1903, he decided to pursue a military career. Graziani was stationed in Italian Eritrea and served in the Italo-Turkish War, where he was promoted to Captain. He saw action in World War I and became the youngest Colonnello (Colonel) in the Regio Esercito.

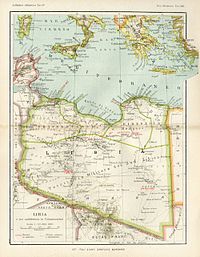

In Libya

In the 1920s, Graziani was appointed by the new Fascist government to be commander the Italian forces in Libya. He was responsible for suppressing the Senussi rebellion. During this so-called "pacification", he was responsible for the construction of several concentration camps and labor camps, where thousands of Libyan prisoners died. Some prisoners were killed[2] by hanging, like Omar Mukhtar, or by shooting, but most prisoners died of starvation or disease. His deeds earned him the nickname "the Butcher of Fezzan"[3] among the Arabs, but he was called by the Italians the Pacifier of Libya (Pacificatore della Libia).

In 1930, he became Vice-Governor of Cyrenaica and held this position until 1934, when it was determined that he was needed elsewhere. In 1935, Graziani was made the Governor of Italian Somaliland.

In Ethiopia

During the Second Italo-Abyssinian War in 1935 and 1936, Graziani was the commander of the southern front. His army invaded Ethiopia from Italian Somaliland and he commanded the Italian forces at the Battles of Genale Doria and the Ogaden. However, Graziani's efforts in the south were secondary to the main invasion launched from Eritrea by Generale Emilio De Bono, later continued by Marshal of Italy Pietro Badoglio. It was Badoglio and not Graziani who entered Addis Ababa in triumph after his "March of the Iron Will". But it was Graziani who said: "The Duce will have Ethiopia, with or without the Ethiopians."

Addis Ababa fell to Badoglio on 5 May 1936. Graziani had wanted to reach Harar before Badoglio reached Addis Ababa, but failed to do so. Even so, on 9 May, Graziani was awarded for his role as commander of the southern front with a promotion to the rank of Marshal of Italy. During his tour of an Ethiopian Orthodox church in Dire Dawa, Graziani fell into a pit covered by an ornate carpet, a trap that he believed had been set by the Ethiopian priests to injure or kill him. As a result, he held Ethiopian clerics in deep suspicion.

After the war, Graziani was made Viceroy of Italian East Africa and Governor-General of Shewa / Addis Ababa. After an unsuccessful attempt by two Eritreans to kill him on 19 February 1937 (and after other murders of Italians in occupied Ethiopia), Graziani ordered a bloody and indiscriminate reprisal upon the conquered country, later remembered by Ethiopians as Yekatit 12. Up to thirty thousand civilians of Addis Ababa were killed indiscriminately; another 1,469 were summarily executed by the end of the next month, and over one thousand Ethiopian notables were imprisoned and then exiled from Ethiopia. Graziani became known as "the Butcher of Ethiopia".[4] In connection with the attempt on his life, Graziani authorized the massacre of the monks of the ancient monastery of Debre Libanos and a large number of pilgrims, who had traveled there to celebrate the feast day of the founding saint of the monastery. Graziani's suspicion of the Ethiopian Orthodox clergy (and the fact that the wife of one of the assassins had briefly taken sanctuary at the monastery) had convinced him of the monks' complicity in the attempt on his life.

From 1939-1941, Graziani was the Commander-in-Chief of the General Staff of the Regio Esercito.

In World War II

At the start of World War II, Graziani was still Commander-in-Chief of the Regio Esercito′s General Staff. After the death of Marshal Italo Balbo in a friendly fire incident on 28 June 1940, Graziani took his place as Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa and as Governor General of Libya.

The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had given Graziani a deadline of 8 August 1940 to start to invade Egypt with the 10th Army. Graziani expressed doubts about the ability of his largely un-mechanized force to defeat the British and put off the invasion for as long as he could.

However, faced with demotion, Graziani ultimately followed orders and elements of the 10th Army invaded Egypt on 9 September. The Italians achieved only modest gains in Egypt and then prepared a series of fortified camps to defend their positions. In November 1940 the British counterattacked and completely defeated the 10th Army during Operation Compass, after which Graziani resigned his commission. On 25 March 1941, Graziani was replaced by General Italo Gariboldi, and Graziani remained inactive for the next two years.

Graziani was the only Italian Marshal to remain loyal to Mussolini after Dino Grandi's Grand Council of Fascism coup. He was appointed Minister of Defense of the Italian Social Republic by Mussolini[5] and oversaw the mixed Italo-German Army Group Liguria (Armee Ligurien). Graziani was able to defeat the Allied Forces in the "Battle of Garfagnana" in December 1944,using a mixed Italian / German force including the "Monte Rosa" alpine division and the "San Marco" marine division.

At the end of the Second World War, Graziani spent a few days in San Vittore prison in Milan before being transferred to Allied control. He was brought back to Africa in Anglo-American custody, staying there until February 1946. Allied forces then felt the danger of his assassination or lynching had passed (many thousands of fascists were murdered in Italy in the summer and autumn of 1945), and returned Graziani to the Procida prison in Italy.

In 1948, a military tribunal sentenced Graziani to 19 years in jail as punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis, but he was released after serving only a few months of the sentence. He was never prosecuted for specific war crimes. Unlike the Germans and Japanese, the Italians were not subjected to prosecutions by Allied tribunals.

In the early 1950s, Graziani had some involvement with the neofascist Movimento Sociale Italiano, and became the "Honorary President" of the MSI party in 1953. In January 1955, Rodolfo Graziani died of natural causes in Rome, aged 72 years.

Trials

The League of Nations failed to try Graziani and other Italian authorities before World War II.[6][7]

In 1943, the Allied Powers agreed to create a new body to replace the League: the United Nations. The "United Nations War Crimes Commission" was created to investigate war crimes.[8] On March 4, 1948, charges against Graziani were presented to the United Nations War Crimes Commission. The commission was presented with evidence of the Italian policy of systematic terrorism and Graziani’s self-admitted intention to execute all Amharas authorities, and cited a telegram from Graziani to General Nasi, in which Graziani had written, “Keep in mind also that I have already aimed at the total destruction of Abyssinian chiefs and notables and that this should be carried out completely in your territories.”[9] The UN commission agreed that there was a prima facie case against eight Italians, including Graziani.[10]

The British Foreign Office consistently opposed Ethiopia’s inclusion in the United Nations War Crimes Commission and the trial on Italian crimes committed during the 1935–1936 invasion. Ethiopian efforts to bring Graziani to trial were frustrated by intransigence from both Italy and Britain; the attempts were finally abandoned in a deal with the Foreign Office, whose support the Government of the Ethiopian Empire considered essential for its Imperial claim on Eritrea.

In 1948, an Italian tribunal condemned Graziani to 19 years. However, he served only four months of his sentence, because his lawyers demonstrated that he "received orders".[11]

Recent controversy

In 2012, a "Fatherland" and "Honour" monument was created as Graziani's tomb in the Italian town of Affile. In August 2012, $160,000 of public money was used to finance a monument in his honor, supplemented by private funding by Ettore Viri, the town of Affile's mayor. Engraved in the mausoleum are the words "Fatherland" and "Honour". Local left-wing politicians and national commentators harshly criticized the monument, whereas the "mostly conservative" population of the town appeared to approve of it.[12] Public funding for the Graziani monument has been suspended by the newly elected Lazio administration after the 2013 regional elections.[13] A statement from Ethiopia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said he did not deserve to be memorialized but rather should continue to be condemned for his war crimes, genocidal activity and crimes against humanity.[13]

Books

Graziani wrote several books,[14] the most important of which are:

- Ho difeso la Patria (una vita per l'Italia)

- Africa settentrionale 1940–41

- Libia redenta

also:

- Verso il Fezzan.

- La reconquista del Fezzan.

- Cirenaica Pacificata.

Military career

- 1915-1918—Service in World War I

- 1921-1934—Service in Libya

- 1926-1930—Vice Governor-General of Italian Cyrenaica

- 1930-1934—Governor-General of Italian Cyrenaica

- 1935-1936—Governor-General of Italian Somaliland

- 1936-1937—Governor-General and Viceroy of Ethiopia; promoted to Marshal of Italy

- 1940-1941—Commander-in-Chief of Italian North Africa and Governor-General of Libya

- 1943-1945—Minister of Defense for the Italian Social Republic

In popular culture

- He was portrayed by actor Oliver Reed in the movie Lion of the Desert.[citation needed]

Bibliography

- Canosa, Romano. Graziani. Il maresciallo d'Italia, dalla guerra d'Etiopia alla Repubblica di Salò. Editore Mondadori; Collana: Oscar storia. EAN 9788804537625

- Del Boca, AngeloNaissance de la nation libyenne, Editions Milelli, 2008, ISBN 978-2-916590-04-2.

- Pankhurst, Richard. History of the Ethiopian Patriots (1936-1940), The Graziani Massacre and Consequences. Addis Abeba Tribune editions.

- Rocco, Giuseppe. L'organizzazione militare della RSI, sul finire della seconda guerra mondiale. Greco & Greco Editori. Milano, 1998

See also

Notes

- ^ "Graziani, Rodolfo". Treccani.it. Enciclopedia Treccani. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Italian atrocities in world war two | Education | The Guardian:# Rory Carroll # The Guardian, # Monday June 25 2001

- ^ Hart, David M.: Muslim Tribesmen and the Colonial Encounter in Fiction and on Film: The Image of the Muslim Tribes in Film and Fiction. Het Spinhuis, 2001. Page 121. ISBN 90-5589-205-X

- ^ Mockler, Anthony (2003). "4". Haile Selassie's War. New York: Olive Branch.

- ^ Video of Graziani in 1944 (in Italian) on YouTube

- ^ Graziani had ordered his troops to use chemical weapons on October 10, 1935 against Ras Nasibu's troops in Gorrahei.(David Hamilton Shinn, Thomas P. Ofcansky, Chris Prouty,Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia,p, 89, The Scarecrow Press, Inc, ISBN 978-0-8108-4910-5)

- ^ Richard Pankhurst states that "The Ethiopian Minister of Foreign Affairs supplied the League of Nations with irrefutable information on Fascist war crimes, including the use of poison gas and the bombing of Red Cross hospitals and ambulances, from within a few hours of the Italian invasion on 3 October 1935 to 10 April of the following year." (Pankhurst, Richard "Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of Their Discussion, from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936–1949)", Northeast African Studies, Volume 6, Number 1-2,1999)

- ^ Ato Ambay of The Ethiopian War Crimes Commission which had begun preliminary research reported to the UN War Crimes Commission on 31 December 1946, that there was no difficulty at all to obtain sufficient evidence to justify a trial against Graziani, because of his crimes against humanity, especially related to the great Graziani massacre in February 1937 (Pankhurst, Richard. "Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of Their Discussion, from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936–1949))

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard "Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of Their Discussion, from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936–1949)", Northeast African Studies, Volume 6, Number 1-2,1999,p. 127

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard "Italian Fascist War Crimes in Ethiopia: A History of Their Discussion, from the League of Nations to the United Nations (1936–1949)", Northeast African Studies, Volume 6, Number 1-2,1999,p. 136

- ^ Rodolfo Graziani biography by Angelo Del Boca in Treccani Enciclopedia Italiana (in Italian)

- ^ New York Times: Monument to Graziani

- ^ a b Bruh Yihunbelay. "The Reporter - English Edition". thereporterethiopia.com.

- ^ "Graziani, Rodolfo". openlibrary.org.

External links

![]() Media related to Rodolfo Graziani at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rodolfo Graziani at Wikimedia Commons

- 1882 births

- 1955 deaths

- Governors of Italian Somaliland

- Governors-General of Italian Libya

- People from the Province of Frosinone

- People of former Italian colonies

- Field marshals of Italy

- Italian East Africa

- Italian fascists

- Italian military personnel of the Italo-Turkish War

- Italian military personnel of World War I

- Italian military personnel of World War II

- Italian military personnel of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

- Italian people convicted of war crimes

- People of the Italian Social Republic

- People convicted of treason

- Italian generals

- Italian anti-communists

- Italian colonial governors and administrators