Rollo

| Rollo | |

|---|---|

Rollo on the Six Dukes statue in Falaise town square. | |

| Count of Rouen | |

| Reign | 911–927 |

| Predecessor | None |

| Successor | William I |

| Born | c. 846 Kingdoms of Møre |

| Died | c. 932 Normandy |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Poppa of Bayeux Gisela of France (existence doubtful) |

| Issue more | William I Gerloc |

| House | House of Normandy |

| Father | Rognvald Eysteinsson |

Rollo (c. 846 – c. 932), in some, later sources identified with Ganger-Hrólf (or as Göngu Hrólfr in the Old Norse language),[1][2][3] and baptised Robert, was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, a region of France. Rollo came from a noble warrior family of Scandinavian origin. After making himself independent of the Norwegian king Harald Fairhair, he sailed off to Scotland, Ireland, England and Flanders on pirating expeditions, and took part in raids along France's Seine river.[4][5] Rollo won a reputation as a great leader of Viking rovers in Ireland and Scotland, and emerged as the outstanding personality among the Norsemen who had secured a permanent foothold on Frankish soil in the valley of the lower Seine.[5] Charles the Simple, the king of West Francia, ceded them lands between the mouth of the Seine and what is now the city of Rouen in exchange for Rollo agreeing to end his brigandage, and provide the Franks with his protection against further incursion by Norse war bands.[6]

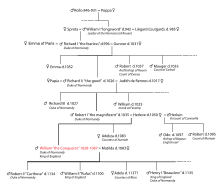

Rollo is first recorded as the leader of these Viking settlers in a charter of 918, and it appears that he continued to reign over the region of Normandy until at least 927. Before his death, he gave his son, William I Longsword, governance of the Duchy of Normandy that he had founded, and after William succeeded him the offspring of Rollo and his men became known as the Normans, under leadership of Rollo's progeny, the Dukes of Normandy.[6] After the Norman conquest of England and their conquest of southern Italy & Sicily over the following two centuries, the descendants of Rollo and his men came to rule Norman England (the House of Normandy), the Kingdom of Sicily (the Kings of Sicily) as well as the Principality of Antioch from the 10th to 12th century AD, leaving behind an enduring legacy in the historical developments of Europe and the Near East.[7][8][9]

Origins

Rollo was born in the latter half of the 9th century somewhere on the Atlantic side of Scandinavia. Details of his origins and parentage are obscured, though it is clear from his later status as a jarl that he belonged to a noble warrior family.[10] Later Norman writers, notably Dudo of Saint-Quentin, refer to Rollo as "Danish", a term then used for the inhabitants of Scandinavia (i.e. those who spoke the Danish tongue).[11][12] Dudo's 11th century work, "De moribus et actis primorum Normannorum ducum", additionally recounts a Danish nobleman at loggerheads with the king of Denmark, who had two sons, Gurim and Rollo; upon his death, Gurim was killed and Rollo was expelled. The historian D. C. Douglas calls this account "manifestly improbable in all its details", as the assertion Rollo originated in Denmark cannot be wholly trusted owing to an alliance between the Duchy and the Kingdom of Denmark at the time of Dudo's writings.[13]

Geoffrey Malaterra, an eleventh-century Benedictine monk and historian, wrote how: "Rollo sailed boldly from Norway with his fleet to the Christian coast."[14] The 12th century English historian William of Malmesbury stated that Rollo was "born of noble lineage among the Norwegians".[15] Rollo also is mentioned in "The Life of Gruffud ap Cynan", a 12th-century history, which refers to him as the youngest of two brothers to the first king of Dublin. The 13th century Icelandic sagas, Heimskringla and Orkneyinga Saga, remember him as Hrólf the Walker ("who was so big that no horse could carry him", hence his byname of Ganger-Hrólf[16]), but offer a contradictory account of his parentage. Both sources mention Rollo was born as Hrólfr Rognvaldsson in Møre, Western Norway, in the late 9th century as a son to the Norwegian jarl Rognvald Eysteinsson. Eysteinsson was known to be an enemy of the two brothers mentioned in The Life of Gruffudd ap Cynan. Richer of Reims, who lived in the 10th century, named Rollo's father as one Catillus, or Ketil.[17] However, the reliability of Richer's account has been dismissed by some scholars, and Ketil is regarded by the historian D. C. Douglas as a legendary figure.[18]

Name

The name "Rollo" is a Latin translation from the Old Norse name Hrólfr, (cf. the latinization of Hrólfr into the similar Roluo in the Gesta Danorum), but Norman people called him by his popular name Rou(f) (see Wace's Roman de Rou).[19] Sometimes his name is turned into the Frankish name Rodolf(us) or Radulf(us) or the French Raoul, that are derived from it.[Note 1]

Biography

According to Dudo, Rollo seized Rouen in 876 and led the Viking fleet which besieged Paris and attacked Bayeux and Évreux between 885 and 887. He subsequently married Poppa, daughter of Berengar, count of Rennes, who gave birth to Rollo's future successor, William Longsword. Douglas dismisses this account, pointing out that Rollo's death in or after 925 makes it very unlikely that he captured Rouen as early as 876, and that he had already fathered William before his arrival in France. Instead, Douglas asserts that Rollo likely came to France no earlier than 900, and probably after 905. Before then, he became an experienced Viking, visiting Scotland and probably Ireland.[20]

The sparsity of northern Gaulish chroniclers in the early 10th century has proved to be a barrier in piecing together Rollo's raids and invasion of the region around the Seine.[21] Rollo is first mentioned in a chronicle in 921, but the earliest documentary evidence of his presence in the region is a charter dated 918, which assigned the Parisian abbey of St Germain des Prés the monastery of La Croix-St Ouen on the Eure; it records "those properties which we have given for the protection of the kingdom of the Northmen on the Seine, that is, Rollo and his associates."[22][23]

There are only one or two contemporary mentions of Rollo.[24] The earliest record is from 918, when an act of Charles the Simple mentions that he conceded land to "Rollo and his associates" for "the protection of the kingdom."[24] The chronicler Flodoard records that Robert of the Breton March waged a campaign against the Vikings, who nearly levelled Rouen and other settlements; eventually, he conceded "certain coastal provinces" to them.[23] Dudo retrospectively stated that this pact took place in 911 at Saint-Clair-sur-Epte; this was roughly the time when the Vikings suffered a defeat at Chartres and the Frankish king, which may have prompted them to negotiate. David Crouch concludes that although probable, it is impossible to verify this;[25] however Douglas agreed with Flodoard's account in the History of the Church at Rheims: after the defeat at Chartres, the Normans formed a pact with Charles and converted to Christianity. He argued that Charles the Simple's plan to invade Lorraine would have also contributed to his willingness to negotiate a settlement in the north.[26][27]

Flodoard explicitly states that Charles granted Rollo and his men the city of Rouen and a number of dependent districts around the coast.[28] Charles was overthrown by a revolt in 923, and his successor, Robert of Neustria, was killed by the Vikings in 924; his successor, Ralph, conceded the Bessin and Maine to Rollo shortly afterwards.[29] Subsequent analyses of the region's place names reveal Scandinavian settlements stretching from the Seine valley to the coast, and from Rouen to Dieppe. However, compared to settlements along eastern England (especially East Anglia and Yorkshire), the appearance of Norse elements in place names was far from widespread or entrenched. The occurrence of the Gallo-Roman suffix "-ville" after Norse names is evidence for this.[30] Around these territories, Normandy emerged, with Rollo and his men gradually adopting the pre-existing administrative and ecclesiastical boundaries they inherited: the archbishopric of Rouen and the traditional civil province, or pagus.

Rollo was alive but frail in 927, when his son is recorded doing homage to King Ralph. His exact death date is not known, but he was certainly dead by 933 and most historians approximate the year of his demise to 928.[31]

Legacy

After pledging his fealty to Charles III as part of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, Rollo divided the lands between the rivers Epte and Risle among his chieftains, and settled with a de facto capital in Rouen. Over time, Rollo and his Vikings converted from Norse paganism to Christianity and intermarried with the native Christian women;[32] with Rollo taking Poppa of Bayeux, daughter of Berengar, the Count of Rennes, as his wife.[33] Their child, William I Longsword, and grandchild, Richard the Fearless, forged the Duchy of Normandy into West Francia's most cohesive and formidable principality.[34] The descendants of Rollo and his men assimilated with their maternal Frankish-Catholic culture and became known as the Normans, lending their name to the region of Normandy.[8]

Rollo is the great-great-great-grandfather of William the Conqueror, or William I of England. Through William, he is one of the ancestors of the present-day British royal family, as well as an ancestor of all current European monarchs and a great many claimants to abolished European thrones. A genetic investigation into the remains of Rollo's grandson, Richard the Fearless, and his great-grandson, Richard the Good, has been announced, with the intention of discerning the origins of the historic Viking leader.[35] The "Clameur de Haro" in the Channel Islands is, supposedly, an appeal to Rollo.

Family

Dudo records that Rollo took Popa (or Poppa), a daughter of Berenger, Count of Rennes, as a wife and with her had their son and Rollo's heir, William. It is impossible to verify this[36] and Douglas dismissed it.[37] Dudo also records that Charles the Simple gave one of his daughters, Gisela, in marriage to Rollo, but Douglas considers this in the "highest degree improbable".[38] Douglas accepts a story from an Icelandic saga that, while in Scotland, Rollo married a Christian woman and had a daughter, Kathleen; according to the sagas, she married a Scottish King called Beolan, and had at least a daughter called Nithbeorg, who was taken captive by and married to Helgi Ottarson.[39] Another daughter, Gerloc or Adele, who married William III, Duke of Aquitaine,[40] was identified by Dudo (who does not name the mother)[41] and accepted by Crouch as a daughter of Rollo and Popa,[42] an identification made by William of Jumieges in the latter-half of the 11th century.[43]

Depictions in fiction

Rollo is the subject of the seventeenth century play Rollo Duke of Normandy written by John Fletcher, Philip Massinger, Ben Jonson, and George Chapman.

A character, loosely based on the historical Rollo and played by Clive Standen, is Ragnar Lothbrok's brother in the History Channel television series Vikings.[44]

See also

Notes

- ^ Rou is the result of a series of French regular phonetic changes from Hrólfr > Rolf > Rouf to Rou (see Lepelley 15–16) and Norman names in -ouf and -ou(t) : I(n)gouf and Ygout < Old Norse Ingulfr / Ingólfr (Old Danish Ingulf). The variant form Rollo is just a latinization of the root Rol(l)- + Latin suffix -o / -one-, after the Latin names in -o. cf. Cicero / Cicerone and the latinized Germanic short names in -o > -o / -on, instead of -an in Germanic cf. Bero / Beran (see Lepelley 15–16). That is the reason why his name is Rollon in Standard French. Rollo is also known in the documents as Radulf(us) (Old Low Franconian) (or sometimes Rodulf(us)) > French Raoul, that is the French translation of Hróðulfr > Hrólfr, according to the Low Franconian variant form Radulf of Germanic Rodulf / Rudolf.

References

- ^ Sarah Orne Jewett, The Normans, Chapter II: Dukes of Normandy: ROLF THE GANGER

- ^ Charles Cawley, F.M.G., Chapter 1. Dukes of Normandy 911-1106

- ^ Frederick Lewis Weis, Ancestral Roots, Line 121E - 19 states

- ^ "Rollo Duke of Normandy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Norman". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b Bates Normandy Before 1066 pp. 8–10

- ^ "The Norman Impact". History Today Volume 36 Issue 2. History Today. 2 February 1986. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Sicilian Peoples: The Normans". L. Mendola & V. Salerno. Best of Sicily Magazine. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ Lars Brownworth, Episode I: Rollo and the Viking Age

- ^ Crouch 2002, p. 1

- ^ Dudo of Saint-Quentin

- ^ Vikings at war, Vegard Vike & Kim Hjardar

- ^ (Douglas 1942, pp. 418-419)

- ^ The Deeds of Count Roger of Calabria & Sicily & of Duke Robert Guiscard his brother, Geoffery Malaterra. Translated by Graham A. Loud

- ^ Sharpe, Rev. J. (trans.), revised Stephenson, Rev. J. (1854) William of Malmesbury, The Kings before the Norman Conquest (Seeleys, London, reprint Llanerch, 1989), II, 127, p. 110.

- ^ Orkneyinga saga (1981) Chapter 4 - " To Shetland and Orkney" pp. 26-27

- ^ Crouch 2002, pp. 297-300

- ^ Douglas 1942, p. 420

- ^ René Lepelley, Guillaume le duc, Guillaume le roi : extraits du Roman de Rou de Wace, Centre de publications de l'Université de Caen, Caen, 1987, p. 15 and 16.

- ^ Douglas 1942, pp. 424-425

- ^ Douglas 1942, p. 425

- ^ Douglas 1942, pp. 425-426

- ^ a b Crouch 2002, p. 3

- ^ a b Crouch, 2002 pg. 3

- ^ Crouch 2002, p. 4

- ^ Douglas 1942, pp. 427-428

- ^ Rollo likely converted to Christianity and adopted the name Robert (Crouch 2002, p. 8)

- ^ Douglas 1942, pp. 429-430

- ^ Crouch, p. 6

- ^ Crouch 2002, pp. 5-6

- ^ Crouch 2002, p. 8

- ^ Bates Normandy Before 1066 pp. 20–21

- ^ Stewart Baldwin, F.A.S.G., Henry Project:"Poppa"

- ^ Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 89

- ^ "Viking is 'forefather to British Royals'". Views and News from Norway. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Crouch 2002, p. 25

- ^ Douglas 1942, p. 424, fn. 5

- ^ Douglas 1942, p. 429, fn. 4

- ^ Douglas 1942, pp. 422 and 435

- ^ Crouch 2002, pp. 9 and 298

- ^ Christiansen 1998, pp. 69-70 and 201

- ^ Crouch 2002, p. 5 (table 1)

- ^ Guillaume de Jumièges [ed. van Houts 1992], vol. 1, pp. 68-69

- ^ Turnbow, Tina (18 March 2013). "Reflections of a Viking by Clive Standen". Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

Sources

- Christiansen, Eric (ed. and trans.) (1998). Dudo of St. Quentin, History of the Normans. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press

- Crouch, David (2002). The Normans: the History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London. ISBN 1 85285 387 5

- Douglas, D.C (1942). "Rollo of Normandy", English Historical Review, Vol. 57, pp. 414–436

- William of Jumieges, and van Houts, Elizabeth (ed.) (1992). The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges, Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Torigni

Further reading

Primary texts

- Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Trans. Pálsson, Hermann and Edwards, Paul. Hogarth Press, London, 1978. ISBN 0-7012-0431-1. Republished 1981, Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044383-5.

Secondary texts

- Arbman, Holgar (1961). Ancient People and Places: The Vikings. Thames and Hudson.

- Christiansen, Eric (2002). The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Fitzhugh, William W. and Ward, Elizabeth (2000). Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- van Houts, Elisabeth (2000). The Normans in Europe. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

- Jones, Gwyn (1984). A History of the Vikings, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press

- Konstam, Agnus (2002). Historical Atlas of the Viking World. Checkmark Books

- McKitterick, Rosamond (1983). The Frankish Kingdom under the Carolingians, 751–987. Longman

- Oxenstierna, Eric (1965). The Norsemen. New York Graphics Society Publishers, Ltd.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1992). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway, translated Lee M. Hollander. Reprinted Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73061-6