Scandinavian Peninsula

| Part of a series on |

| Scandinavia |

|---|

|

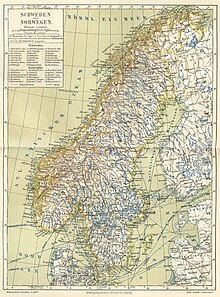

The Scandinavian Peninsula (Template:Lang-sv; Template:Lang-no; Template:Lang-fi; Template:Lang-se; Template:Lang-ru, Skandinavsky poluostrov) is a peninsula in Northern Europe, which covers the whole mainland of Sweden, nearly all the mainland of Norway, northwestern Finland as well as the narrow area to northwest from Kaitakoski, Jäniskoski and Rajakoski both Borisoglebsky settlement in Russia.

The name of the peninsula is derived from the term Scandinavia, the cultural region of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. That cultural name is in turn derived from the name of Scania, the region at the southern extremity of the peninsula which has during periods been part of Denmark, which is the ancestral home of the Danes, and which is now part of Sweden. The derived term "Scandinavian" also refers to the Germanic peoples who speak North Germanic languages, considered to be a dialect continuum derived from Old Norse.[1][2][3][4] These modern North Germanic languages found in Scandinavia are Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish; additionally Faroese and Icelandic belong to the same language group, but they are not part of the modern Scandinavian dialect continuum and are not intelligible with the other languages.

The Scandinavian Peninsula is the largest peninsula of Europe, larger than the Balkan, the Iberian and the Italian peninsulas. During the Ice Ages, the sea level of the Atlantic Ocean dropped so much that the Baltic Sea, the Gulf of Bothnia and the Gulf of Finland disappeared, and the countries now surrounding them, including Germany, Poland, the other Baltic countries and Scandinavia, were directly joined by land.

Geography

Arguably the largest peninsula in Europe, the Scandinavian Peninsula is approximately 1,850 kilometres (1,150 mi)* long with a width varying approximately from 370 to 805 kilometres (230 to 500 miles). The Scandinavian mountain range generally defines the border between Norway and Sweden. The peninsula is bordered by several bodies of water including:

- the Barents Sea to the north

- the Norwegian Sea to the west

- the North Sea and Baltic Sea to the south

- the Baltic Sea, Kemijoki, Lake Inari and Paatsjoki to the east.

Its highest elevation was Glittertinden in Norway at 2,470 m (8,100 ft) above sea level, but since the glacier at its summit partially melted [citation needed], the highest elevation is at 2,469 m (8,100 ft) at Galdhøpiggen, also in Norway. These mountains also have the largest glacier on the mainland of Europe, Jostedalsbreen.

About one quarter of the Scandinavian Peninsula lies north of the Arctic Circle, its northernmost point being at Cape Nordkyn, Norway.

The climate across Scandinavia varies from tundra (Köppen: ET) and subarctic (Dfc) in the north, with cool marine west coast climate (Cfc) in northwestern coastal areas reaching just north of Lofoten, to humid continental (Dfb) in the central portion and marine west coast (Cfb) in the south and southwest.[5] The region is rich in timber, iron and copper with the best farmland in southern Sweden. Large petroleum and natural-gas deposits have been found off Norway's coast in the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

Much of the population of the Scandinavian Peninsula is naturally concentrated in its southern part, which is also its agricultural region. The largest cities of the peninsula are Stockholm, Sweden; Oslo, Norway; Gothenburg, Sweden; Malmö, Sweden and Bergen, Norway, in that order.

Geology

The Scandinavian Peninsula occupies part of the Baltic Shield, a stable and large crust segment formed of very old, crystalline metamorphic rocks. Most of the soil covering this substrate was scraped by glaciers during the Ice Ages of antiquity, especially in northern Scandinavia, where the Baltic Shield is closest to the surface of the land. As a consequence of this scouring, the elevation of the land and the cool-to-cold climate, a relatively small percentage of its land is arable.[6]

The glaciation during the Ice Ages also deepened many of the river valleys, which were invaded by the sea when the ice melted, creating the noteworthy fjords of Norway. In the southern part of the peninsula, the glaciers deposited vast numbers of terminal moraines, configuring a very chaotic landscape.[7] These terminal moraines covered all of what is now Denmark.

Although the Baltic Shield is mostly geologically stable and hence resistant to the influences of other neighbouring tectonic formations, the weight of nearly four kilometres of ice during the Ice Ages caused all of the Scandinavian terrain to sink. When the ice sheet disappeared, the shield rose again, a tendency that continues to this day at a rate of about one metre per century.[7] Conversely, the southern part has tended to sink to compensate, causing flooding of the Low Countries and Denmark.

The crystalline substrate of the land and absence of soil in many places have exposed mineral deposits of metal ores, such as those of iron, copper, nickel, zinc, silver and gold. The very most valuable of these have been the deposits of iron ore in northwestern Sweden. In the 19th century these deposits prompted the building of a railway from northwestern Sweden to the Norwegian seaport of Narvik so that the iron ore could be exported by ship to places like southern Sweden, Germany, Great Britain and Belgium for smelting into iron and steel. This railway is in a region of Norway and Sweden that otherwise do not have any railways because of the very rugged terrain, mountains and fjords of that part of Scandinavia.

People

The first recorded human presence in the southern area of the peninsula and Denmark dates from 12,000 years ago.[8] As the ice sheets from the glaciation retreated, the climate allowed a tundra biome that attracted reindeer hunters. The climate warmed up gradually, favouring the growth of evergreen trees first and then deciduous forest which brought animals like aurochs. Groups of hunter-fisher-gatherers started to inhabit the area from the Mesolithic (8200 BC), up to the advent of agriculture in the Neolithic (3200 BC).

The northern and central part of the peninsula is partially inhabited by the Sami, often referred to as "Lapps" or "Laplanders," who began to arrive several thousand years after the Scandinavian Peninsula had already been inhabited in the south. In the earliest recorded periods they occupied the arctic and subarctic regions as well as the central part of the peninsula as far south as Dalarna, Sweden. They speak the Sami language, a non-Indo-European language of the Uralic family which is related to Finnish and Estonian. The first inhabitants of the peninsula were the Norwegians on the west coast of Norway, the Danes in what is now southern and western Sweden and southeastern Norway, the Svear in the region around Mälaren as well as a large portion of the present day eastern seacoast of Sweden and the Geats in Västergötland and Östergötland. These peoples spoke closely related dialects of an Indo-European language, Old Norse. Although political boundaries have shifted, descendants of these peoples still are the dominant populations in the peninsula in the early 21st century.[9]

Political development

Although the Nordic countries look back on more than 1,000 years of history as distinct political entities, the international boundaries came late and emerged gradually. It was not until the middle of the 17th century that Sweden had a secure outlet on the Kattegat and control of the south Baltic coast. The Swedish and Norwegian boundaries were finally agreed and marked out in 1751. The Finnish-Norwegian border on the peninsula was established after extensive negotiation in 1809, and the common Norwegian-Russian districts were not partitioned until 1826. Even then the borders were still fluid, with Finland gaining access to the Barents Sea in 1920, but ceding this territory to Russia in 1944.[10]

Denmark, Sweden and the Russian Empire dominated the political relationships on the Scandinavian Peninsula for centuries, with Iceland, Finland and Norway only gaining their full independence during the 20th century. The Kingdom of Norway – long held in personal union by Denmark – fell to Sweden after the Napoleonic Wars and only attained full independence in 1905. Having been an autonomous grand duchy within the Russian Empire since 1809, Finland declared independence during the Soviet revolution of Russia in 1917. Iceland declared its independence from Denmark in 1944, while Denmark was under the occupation of Nazi Germany. Iceland was encouraged to do this by the British and American armed forces that were defending Iceland from Nazi invasion.

The Wehrmacht invaded Norway in 1940 and the German Army occupied all of Norway until May 1945. With the acquiescence of the Kingdom of Sweden, German troops moved from northern Norway, across northern Sweden, into Finland, which had become an ally of Nazi Germany. Then, in the spring of 1941, the German Army and the Finnish Army invaded the Soviet Union together. The Republic of Finland had a grievance against the Soviet Union because the Red Army had invaded southeastern Finland in the Winter War (1939–40) and had taken a large area of territory away from Finland.

Sweden remained a neutral country during the First World War, Second World War, the Korean War and the Cold War, and it continues its neutral policies as of 2013.

In 1945, Norway, Denmark and Iceland were founding members of the United Nations. Sweden joined the U.N. soon after. Finland joined during the 1950s. The first Secretary General of the United Nations, Trygve Lie, was a Norwegian citizen. The second Secretary General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, was a Swedish citizen. Thus the people of the Scandinavian Peninsula had a strong influence in international affairs during the 20th century.

In 1949, Norway, Denmark and Iceland became founding members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation for their defence against Germany, the Soviet Union and all other potential invaders, and these three countries remain members as of 2011.

Sweden and Finland joined the European Union in 1995. Norway, however, remains outside the Union.

See also

-

An aerial view of the Scandinavian Peninsula

-

Scandinavian Peninsula in winter (19 February 2003)

References

- ^ Haugen, Einar (1976). The Scandinavian Languages: An Introduction to Their History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- ^ Helle, Knut (2003). "Introduction". The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Ed. E. I. Kouri et al. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-47299-7. p. XXII. "The name Scandinavia was used by classical authors in the first centuries of the Christian era to identify Skåne and the mainland further north which they believed to be an island."

- ^ Olwig, Kenneth R. "Introduction: The Nature of Cultural Heritage, and the Culture of Natural Heritage—Northern Perspectives on a Contested Patrimony". International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005, p. 3: The very name 'Scandinavia' is of cultural origin, since it derives from the Scanians or Scandians (the Latinized spelling of "Skåninger"), a people who long ago lent their name to all of Scandinavia, perhaps because they lived centrally, at the southern tip of the peninsula."

- ^ Østergård, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity – From Composite States to Nation States". The Cultural Construction of Norden. Øystein Sørensen and Bo Stråth (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997, 25-71.

- ^ Glossary of American climate terminology in terms of Köppens classification

- ^ Hobbs, Joseph J. and Salter, Christopher L.Essentials Of World Regional Geography,p. 108.Thomson Brooks/Cole.2005.ISBN 0-534-46600-1

- ^ a b Ostergren, Robert C., Rice, John G. The Europeans. Guilford Press. 2004.ISBN 0-89862-272-7

- ^ Tilley, Christopher Y. Ethnography of the Neolithic: Early Prehistoric Societies in Southern Scandinavia, p. 9, Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-521-56821-8

- ^ Sawyer, Bridget and Peter (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from conversion to Reformation, circa 800-1500. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1738-4.

- ^ Sømme, Axel (Ed.) (1961). The Geography of Norden. Oslo: Den Norske nasjonalkommittee for geographi. ISBN none.