Second Battle of the Marne

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

| Second Battle of the Marne | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||

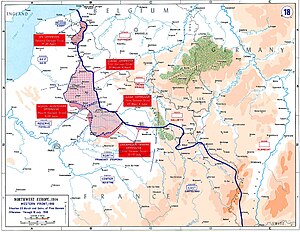

German Offensives 1918 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Erich Ludendorff Karl von Einem Bruno von Mudra Max von Boehn | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

44 French divisions 8 American divisions 4 British divisions 2 Italian divisions 408 heavy guns 360 field batteries 346 tanks |

52 divisions 609 heavy guns 1,047 field batteries | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

139,000 dead or wounded 29,367 captured 793 guns lost | ||||||

The Second Battle of the Marne (Template:Lang-fr), or Battle of Reims (15 July – 6 August 1918) was the last major German offensive on the Western Front during the First World War. The attack failed when an Allied counterattack by French and American forces, including several hundred tanks, overwhelmed the Germans on their right flank, inflicting severe casualties. The German defeat marked the start of the relentless Allied advance which culminated in the Armistice with Germany about 100 days later.

Background

Following the failure of the Spring Offensive to end the conflict, Erich Ludendorff, Chief Quartermaster General (he had disapproved of "Second Chief of the General Staff" as a rank) and virtual military ruler of Germany, believed that an attack through Flanders would give Germany a decisive victory over the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the most experienced Allied force on the Western Front at that time. To shield his intentions and draw Allied troops away from Belgium, Ludendorff planned for a large diversionary attack along the Marne.

German attack

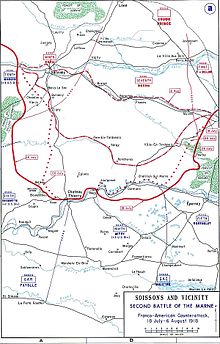

The battle began on 15 July 1918 when 23 German divisions of the First and Third armies—led by Bruno von Mudra and Karl von Einem—assaulted the French Fourth Army under Henri Gouraud east of Reims (the Fourth Battle of Champagne (Template:Lang-fr)). The U.S. 42nd Division was attached to the French Fourth Army and commanded by Gouraud at the time. Meanwhile, 17 divisions of the German Seventh Army, under Max von Boehn, aided by the Ninth Army under Johannes von Eben, attacked the French Sixth Army led by Jean Degoutte to the west of Reims (the Battle of the Mountain of Reims (Template:Lang-fr)). Ludendorff hoped to split the French in two.

The German attack on the east of Reims was stopped on the first day, but west of Reims the offensive fared better. The defenders of the south bank of the Marne could not escape the three-hour fury of the German guns. Under cover of gunfire, stormtroopers swarmed across the river in every sort of transport—30-man canvas boats or rafts. They began to erect skeleton bridges at 12 points under fire from those Allied survivors who had not been suppressed by gas or artillery fire. Some Allied units, particularly the 3rd U.S. Infantry Division "Rock of the Marne", held fast or even counterattacked, but by the evening, the Germans had captured a bridgehead either side of Dormans 4 mi (6.4 km) deep and 9 mi (14 km) wide, despite the intervention of 225 French bombers, which dropped 44 short tons (40 t) of bombs on the makeshift bridges.

The British XXII Corps and 85,000 American troops joined the French for the battle, and stalled the advance on 17 July 1918.

Allied counter-offensive

The German failure to break through, or to destroy the Allied armies in the field, allowed Ferdinand Foch, the Allied Supreme Commander, to proceed with the planned major counteroffensive on 18 July; 24 French divisions, including the 92nd Infantry Division (United States) and 93rd Infantry Division (United States) under French command, joined by other Allied troops including eight large U.S. divisions under U.S. command and 350 tanks attacked the recently formed German salient.

The Allied preparation was very important in countering the German offensive. It was believed that the Allies had the complete picture of the German offensive in terms of intentions and capabilities. The Allies knew the key points of the German plan down to the minute.[1] There is a legend, possibly true, that engineer Cpt. Hunter Grant, along with the help of engagement coordinator and engineer Cpt. Page, devised a deceptive ruse. A briefcase with false plans for an American counterattack was handcuffed to a man who had died of pneumonia and placed in a vehicle which appeared to have run off the road at a German-controlled bridge. The Germans, on finding and being taken in by these plans, then adjusted their attack to thwart the false Allied plan. Consequently, the French and American forces led by Foch were able to unleash a different attack on exposed parts of the enemy lines, leaving the Germans with no choice but to retreat. This engagement marked the beginning of a German withdrawal that was never effectively reversed. In September 1918 nine American divisions (about 243,000 men) joined four French divisions to push the Germans from the St. Mihiel salient.[2]

By May, Foch had spotted flaws in the German offensives.[3] The force which defeated the German offensive was mainly French, with American, British and Italian support. Co-ordinating this counter-attack would be a major problem as Foch had to work with "four national commanders but without any real authority to issue order under his own name[...]they would have to fight as a combined force and to overcome the major problems of different languages, cultures, doctrines and fighting styles."[3] However, the presence of fresh American troops, unbroken by years of war, significantly bolstered Allied resistance to the German offensive. Floyd Gibbons wrote about the American troops, saying, "I never saw men charge to their death with finer spirit."[4]

On 19 July, the Italian Corps lost 9,334 officers and men out of a total fighting strength of about 24,000. Nevertheless, Berthelot rushed two newly arrived British infantry divisions, the 51st (Highland) and 62nd (West Riding),[5] through the Italians straight into attack down the Ardre Valley (the Battle of Tardenois (Template:Lang-fr)—named after the surrounding Tardenois plain).

The Germans ordered a retreat on 20 July and were forced back to the positions from which they had started their Spring Offensives. They strengthened their flank positions opposite the Allied pincers and on the 22nd, Ludendorff ordered to take up a line from the upper Ourcq to Marfaux.

Costly Allied assaults continued for minimal gains. By 27 July, the Germans had withdrawn their center behind Fère-en-Tardenois and had completed an alternative rail link. The Germans retained Soissons in the west.

On 1 August, French and British divisions of Mangin's Tenth Army renewed the attack, advancing to a depth of nearly 5 mi (8.0 km). The Allied counterattack petered out on 6 August in the face of German offensives. By this stage, the salient had been reduced and the Germans had been forced back to a line running along the Aisne and Vesle Rivers; the front had been shortened by 28 mi (45 km).

The Second Battle of the Marne was an important victory. Ferdinand Foch received the baton of a Marshal of France. The Allies had taken 29,367 prisoners, 793 guns and 3,000 machine guns and inflicted 168,000 casualties on the Germans. The primary importance of the battle was its morale aspect: the strategic gains on the Marne marked the end of a string of German victories and the beginning of a series of Allied victories that were in three months to bring the German Army to its knees.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Michael S. Neiberg. The Second Battle of the Marne, 2008, p. 91

- ^ Kennedy, David (2008). The American pageant: a history of the American people. Cengage Learning. p. 708. ISBN 978-0-547-16654-4.

- ^ a b Neiberg, p. 7

- ^ Byron Farwell, Over There: The United States in the Great War, p.169.

- ^ Everard Wyrall, The History of the 62nd (West Riding) Division 1914-1919 (undated but about 1920-25. See 62 Div external link below).

Further reading

- Greenwood, Paul (1998). The Second Battle of the Marne. Airlife Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84037-008-9.

- Neiberg, Michael (2008). The Second Battle of the Marne. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35146-3.

- Skirrow, Fraser (2007). Massacre on the Marne. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-496-8.

- Read, I.L. (1994). Of Those We Loved. Preston: Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85821-225-8.

- Farwell, Byron (1999). Over There: The United States in the Great War, 1917-1918. New York: Norton Paperback. ISBN 0-393-32028-6.