Siege tower

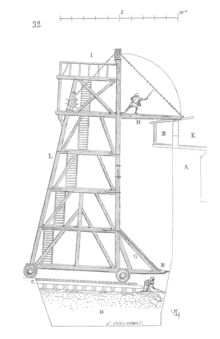

A siege tower (or in the Middle Ages a belfry[1]) is a specialized siege engine, constructed to protect assailants and ladders while approaching the defensive walls of a fortification. The tower was often rectangular with four wheels and a height roughly equal to that of the wall or sometimes higher to allow archers to stand on top of the tower and fire into the fortification. Because the towers were wooden and thus flammable, they had to have some non-flammable covering of iron or fresh animal skins.[1] The siege tower was mainly made from wood but sometimes they had metal parts.

Used since the 9th century BC in the ancient Near East, 305 BC in Europe and also in antiquity in the Far East, siege towers were of unwieldy dimensions and, like trebuchets, were therefore mostly constructed on site of the siege. Taking considerable time to construct, siege towers were mainly built if the defense of the opposing fortification could not be overcome by ladder assault, by mining or by breaking walls or gates. It's attack was ferocious and it is described as one of the worst siege weapons.

The siege tower sometimes housed pikemen, swordsmen, or crossbowmen who shot quarrels at the defenders. Because of the size of the tower it would often be the first target of large stone catapults but it had its own projectiles with which to retaliate.[1]

Siege towers were used to get troops over an enemy wall. When a siege tower was near a wall, it would drop a gangplank between it and the wall. Troops could then rush onto the walls and into the castle or city.

Ancient use

The first known siege towers were used by the armies of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 9th century BC, under Ashurnasirpal II (r. 884 BC-859 BC). Reliefs from his reign, and subsequent reigns, depict siege towers in use with a number of other siegeworks, including ramps and battering rams. One of the oldest references to the mobile siege tower in ancient China was ironically a written dialogue primarily discussing naval warfare. In the Chinese Yuejueshu (Lost Records of the State of Yue) compiled by the later Han Dynasty Yuan Kang in the year 52 AD, it was recorded that Wu Zixu (526 BC-484 BC) was discussing different ship types to King Helü of Wu (r. 514 BC-496 BC) while explaining military preparedness. After labeling the types of warships used, Wu Zixu said:

Nowadays in training naval forces we use the tactics of land forces for the best effect. Thus great wing ships correspond to the army's heavy chariots, little wing ships to light chariots, stomach strikers to battering rams, castle ships to mobile assault towers, and bridge ships to light cavalry.[2]

Centuries after they were employed in Assyria, the use of the siege tower spread throughout the Mediterranean. The biggest siege towers of antiquity, such as the Helepolis (meaning "The Taker of Cities") of the siege of Rhodes in 305 BC, could be as high as 135 feet and as wide as 67.5 feet.Such large engines would require a capstan to be moved effectively. It was manned by 200 soldiers was divided into nine stories; the different levels housed various types of catapults and ballistae. Subsequent siege towers down through the centuries often had similar engines.

But this huge tower was defeated by the defenders by flooding the ground in front of the wall, creating a moat that caused the tower to get bogged in the mud. The siege of Rhodes illustrates the important point that the larger siege towers needed level ground. Many castles and hill-top towns and forts were virtually invulnerable to siege tower attack simply due to topography. Smaller siege towers might be used on top of siege-mounds, made of earth, rubble and timber mounds in order to overtop a defensive wall. The remains of such a siege-ramp at Masada, for example, has survived almost 2,000 years and can still be seen today.

On the other hand, almost all the largest cities were on large rivers, or the coast, and so did have part of their circuit wall vulnerable to these towers. Furthermore, the tower for such a target might be prefabricated elsewhere and brought dismantled to the target city by water. In some rare circumstances, such towers were mounted on ships to assault the coastal wall of a city: at the siege of Cyzicus during the Third Mithridatic War, for example, towers were used in conjunction with more conventional siege weapons.[3]

Medieval and later use

With the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West into independent states, and the Eastern Roman Empire on the defensive, the use of siege towers reached its height during the medieval period. Siege towers were used when the Avars laid siege unsuccessfully to Constantinople in 626, as the Chronicon Paschale recounts:

"And in the section from the Polyandrion Gate as far as the Gate of St Romanus he prepared to station twelve lofty siege towers, which were advanced almost as far as the outworks, and he covered them with hides." [4]

At this siege the attackers also made use of "sows" - mobile armoured shelters which were used throughout the medieval period, and allowed workers to fill in moats with protection from the defenders (thus levelling the ground for the siege towers to be moved to the walls). However, the construction of a sloping talus at the base of a castle wall (as was common in Crusader fortification[5]) could have reduced the effectiveness of this tactic to an extent.

Siege towers also became more elaborate during the medieval period; at the Siege of Kenilworth Castle in 1266, for example, 200 archers and 11 catapults operated from a single tower.[1] Even then, the siege lasted almost a year, making it the longest siege in English history. They were not invulnerable either, as during the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, Ottoman siege towers were sprayed by the defenders with Greek fire.[4]

Siege towers became vulnerable and obsolete with the development of large cannon. They had only ever existed to get assaulting troops over high walls and large cannon also made high walls obsolete as fortification took a new direction. However, later constructions known as battery-towers took on a similar role in the gunpowder age; like siege-towers, these were built out of wood on site for mounting siege artillery. One of these was built by the Russian military engineer Ivan Vyrodkov during the siege of Kazan in 1552 (as part of the Russo-Kazan Wars), and could hold ten large-calibre cannon and 50 lighter cannons. [6]

Modern image

Although siege towers have long been obviated as a military unit, they have appeared in several films: they were notably featured in Peter Jackson's film The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) during the siege of Minas Tirith, and also in the 2005 film Kingdom of Heaven. They are popular, though not necessarily common, in both historical and fantasy miniature wargaming, such as The Lord of the Rings Strategy Battle Game. The Real mario and princess peach Empire Earth also features siege towers as a unit.

The computer game Age of Mythology features Helepolis units for the Greek forces, firing ballistae from range and being able to garrison other units as well as Egyptian Siege Towers which ram buildings, fire arrows at units and can also garrison units. The older Age Of Empires I game also features Helepolis units, but instead as the upgraded version of the ballista. Rome: Total War and Medieval II: Total War offer a more realistic rendition of siege towers, used for attacking fortified walls.

Additionally, although the rook in Chess originally symbolized a chariot, European adaptations of the game may have been influenced at least in part by Siege towers.

Modern use

As an example of the extremely rare use of something resembling siege towers in present times, the machinery used by police forces to enter Ungdomshuset in Copenhagen, Denmark should be mentioned. On 1 March 2007, armored police officers were lifted to the upper levels of the building using small boom cranes. The officers were placed in containers which were lifted to the windows, thus enabling the police to gain access to the illegally held structure.[citation needed]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Castle: Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections. Dorling Kindersley Pub (T); 1st American edition (September 1994). ISBN 978-1564584670

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Page 678.

- ^ Siege Warfare in the Roman World, 146 BC–AD 378, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-782-4

- ^ a b The Walls of Constantinople, AD 324–1453, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-759-X.

- ^ Crusader Castles in the Holy Land 1192–1302, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1841768278.

- ^ Russian Fortresses, 1480–1682, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-916-9