Basilar skull fracture

| Basilar skull fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Basal skull fracture, skull base fractures[1] |

| |

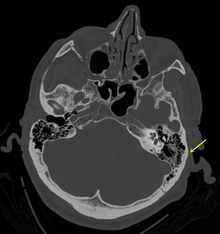

| A subtle temporal bone fracture as seen on a CT scan | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, neurosurgery |

| Symptoms | Bruising behind the ears, bruising around the eyes, blood behind the ear drum[1] |

| Complications | Cerebrospinal fluid leak, facial fracture, meningitis[2][1] |

| Types | Anterior, central, posterior[1] |

| Causes | Trauma[1] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan[1] |

| Treatment | Based on injuries inside the skull[1] |

| Frequency | ≈12% of severe head injuries[1] |

A basilar skull fracture is a break of a bone in the base of the skull.[1] Symptoms may include bruising behind the ears, bruising around the eyes, or blood behind the ear drum.[1] A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak occurs in about 20% of cases and may result in fluid leaking from the nose or ear.[1] Meningitis occurs in about 14% of cases.[2] Other complications include injuries to the cranial nerves or blood vessels.[1]

A basilar skull fracture typically requires a significant degree of trauma to occur.[1] It is defined as a fracture of one or more of the temporal, occipital, sphenoid, frontal or ethmoid bone.[1] Basilar skull fractures are divided into anterior fossa, middle fossa and posterior fossa fractures.[1] Facial fractures often also occur.[1] Diagnosis is typically by CT scan.[1]

Treatment is generally based on the extent and location of the injury to structures inside the head.[1] Surgery may be performed to seal a CSF leak that does not stop, to relieve pressure on a cranial nerve or repair injury to a blood vessel.[1] Prophylactic antibiotics do not provide a clinical benefit in preventing meningitis.[2][3] A basilar skull fracture occurs in about 12% of people with a severe head injury.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

- Battle's sign – bruising of the mastoid process of the temporal bone.

- Raccoon eyes – bruising around the eyes, i.e. "black eyes"

- Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea

- Cranial nerve palsy

- Bleeding (sometimes profuse) from the nose and ears

- Hemotympanum

- Conductive or perceptive deafness, nystagmus, vomiting

- In 1–10% of patients, optic nerve entrapment occurs.[4] The optic nerve is compressed by the broken skull bones, causing irregularities in vision.

- Serious cases usually result in death

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Basilar skull fractures include breaks in the posterior skull base or anterior skull base. The former involve the occipital bone, temporal bone, and portions of the sphenoid bone; the latter, superior portions of the sphenoid and ethmoid bones. The temporal bone fracture is encountered in 75% of all basilar skull fractures and may be longitudinal, transverse or mixed, depending on the course of the fracture line in relation to the longitudinal axis of the pyramid.[5]

While not absolute, three principal types of basilar skull fractures are recognized, based on the direction and location of the impacting force:

- Longitudinal fracture: This type divides the base of the skull into two halves (right and left). It may result from blunt impact on the face, forehead, back of the head, or from front-to-back crushing forces.[6]

- Transverse fracture: This type divides the base of the skull into a front and rear half. It occurs from impact on either side of the head or from side-to-side compression. The fracture typically runs through the petrous portion of the temporal bones and the sella turcica, potentially affecting the pituitary gland. Blood from both ears often indicates this type of fracture, which is the most common basilar skull fracture. Transverse fractures may extend into the orbital roofs or the ethmoid plate, causing periorbital hemorrhage or extensive nasal bleeding, respectively. A fracture through the sella can lead to profuse blood aspiration. A common mechanism for transverse fractures is a sharp blow to the chin, such as a fall onto a hard surface. The impact energy transfers to the skull base via the mandibular rami and temporomandibular joints. The chin injury may appear minor, often just a small abrasion or laceration.[6]

- Ring fracture: This type separates the rim of the foramen magnum, the outlet at the base of the skull through which the brain stem exits and becomes the spinal cord, from the rest of the skull base. This may result in injury to the blood vessels and nerves exiting the foramen magnum.[7] This can manifest as loss of facial nerve or oculomotor nerve function, or hearing loss due to damage to cranial nerve VIII.[4] This type of fracture typical results from a fall from height where the victim lands on their feet or buttocks, forcing the skull down onto the vertebral column.[6]

In children, fractures may not occur due to suture separation and greater bone flexibility.

Management

[edit]Evidence does not support the use of preventive antibiotics, regardless of the presence of a cerebrospinal fluid leak.[3][2]

Prognosis

[edit]Non-displaced fractures usually heal without intervention. Patients with basilar skull fractures are especially likely to get meningitis.[8] The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in these cases is uncertain.[9]

Temporal bone fractures

[edit]Acute injury to the internal carotid artery (carotid dissection, occlusion, pseudoaneurysm formation) may be asymptomatic or result in life-threatening bleeding. They are almost exclusively observed when the carotid canal is fractured, although only a minority of carotid canal fractures result in vascular injury. Involvement of the petrous segment of the carotid canal is associated with a relatively high incidence of carotid injury.[10]

Motor racing accidents

[edit]Basilar skull fractures are a common cause of death in many motor racing accidents. Drivers who have died as a result of basilar skull fractures include Formula One driver Roland Ratzenberger; IndyCar drivers Bill Vukovich Sr., Tony Bettenhausen Sr., Floyd Roberts, and Scott Brayton; NASCAR drivers Dale Earnhardt Sr., Adam Petty, Tony Roper, Kenny Irwin Jr., Neil Bonnett, John Nemechek, J. D. McDuffie, and Richie Evans; CART drivers Jovy Marcelo, Greg Moore, and Gonzalo Rodriguez; and ARCA drivers Blaise Alexander and Slick Johnson. Ernie Irvan is a survivor of a basilar skull fracture sustained at an accident during practice at the Michigan International Speedway in 1994.[11] Race car drivers Stanley Smith and Rick Carelli also survived a basilar skull fracture.[12][13]

To prevent basilar skull fractures, many motorsports sanctioning bodies mandate the use of head and neck restraints, such as the HANS device.[14][15][16][17] The HANS device has demonstrated its life-saving abilities multiple times, including Jeff Gordon at the 2006 Pocono 500, Michael McDowell at the Texas Motor Speedway in 2008,[18] Robert Kubica at the 2007 Canadian Grand Prix, and Elliott Sadler at the 2003 EA Sports 500/2010 Sunoco Red Cross Pennsylvania 500.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Baugnon, KL; Hudgins, PA (August 2014). "Skull base fractures and their complications". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 24 (3): 439–65, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2014.03.001. PMID 25086806.

- ^ a b c d Nellis, JC; Kesser, BW; Park, SS (January 2014). "What is the efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics in basilar skull fractures?". The Laryngoscope. 124 (1): 8–9. doi:10.1002/lary.23934. PMID 24122671.

- ^ a b Ratilal, Bernardo O; Costa, João; Pappamikail, Lia; Sampaio, Cristina; Ratilal, Bernardo O (2015). "Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD004884. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004884.pub4. PMC 10554555. PMID 25918919.

- ^ a b Pediatric Head Trauma at eMedicine

- ^ Skull Fracture at eMedicine

- ^ a b c Spitz, Werner U.; Spitz, Daniel J.; Fisher, Russell S., eds. (2006). Spitz and Fisher's medicolegal investigation of death: guidelines for the application of pathology to crime investigation (4th ed.). Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas. ISBN 978-0-398-07544-6.

- ^ "About Brain Injury". Brain Injury Association of America. October 12, 2012. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ^ Dagi, T.Forcht; Meyer, Frederick B.; Poletti, Charles A. (1983). "The incidence and prevention of meningitis after basilar skull fracture". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1 (3): 295–8. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(83)90109-2. PMID 6680635.

- ^ Butler, John. "Antibiotics in base of skull fractures". BestBets. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- ^ Resnick, Daniel K.; Subach, Brian R.; Marion, Donald W. (1997). "The Significance of Carotid Canal Involvement in Basilar Cranial Fracture". Neurosurgery. 40 (6): 1177–81. doi:10.1097/00006123-199706000-00012. PMID 9179890.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckT7z-XwKUo Dale Jr. Download: Ernie Irvan's Horrific Crash

- ^ Zenor, John (June 9, 2001). "Former Winston Cup driver Smith leaves horrid accident in past". Arizona Daily Sun. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Wack, Craig (June 21, 2009). "Rick Carelli's seat safer than '99 Trucks Series ride". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ "FIA makes HANS device mandatory". Autosport. Autosport Media UK. 9 December 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "NASCAR mandates HANS for 3 series". The Washington Times. The Washington Times LLC. 18 October 2001. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "MSA confirms Motor Sports Council decisions regarding Frontal Head Restraints". MSA. Motor Sports Association. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Head and Neck Restraints Mandatory!". NNJR SCCA. Sports Car Club of America. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ ANDERSON, LARS. "HOW SAFE IS RACING?". SI.com. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ "Sadler: Sunday's crash hardest in Cup history". ESPN.com. 2010-08-03. Retrieved 2018-04-04.