Starfish

| Starfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | Asteroidea De Blainville, 1830

|

| Orders | |

|

Brisingida | |

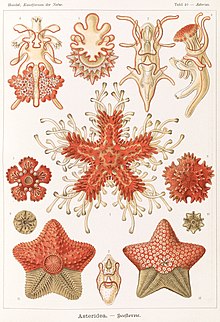

Starfish or sea stars are echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea.[2] The names "starfish" and "sea star" essentially refer to members of the class Asteroidea. However, common usage frequently finds these names also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as "brittle stars" or "basket stars". About 1,800 living species of starfish occur in all the world's oceans, including the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic and Southern Ocean regions. Starfish occur across a broad depth range from the intertidal to abyssal depths of greater than 6,000 m (20,000 ft).

Starfish are among the most familiar of marine animals found on the seabed. They typically have a central disc and five arms, though some species have many more arms than this. The aboral or upper surface may be smooth, granular or spiny, and is covered with overlapping plates. Many species are brightly coloured in various shades of red or orange, while others are blue, grey, brown, or drab. Starfish have tube feet operated by a hydraulic system and a mouth at the centre of the oral or lower surface. They are opportunistic feeders and are mostly predators on benthic invertebrates. Several species having specialized feeding behaviours, including suspension feeding and adaptations for feeding on specific prey. They have complex life cycles and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most can regenerate damaged or lost arms.

The Asteroidea occupy several important roles throughout ecology and biology. Starfish, such as the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus), have become widely known as an example of the keystone species concept in ecology. The tropical crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) is a voracious predator of coral throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Other starfish, such as members of the Asterinidae, are frequently used in developmental biology.

Taxonomy and evolutionary history

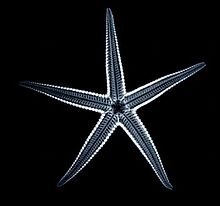

The Asteroidea are a large and speciose class within the phylum Echinodermata. Like other classes in that group, members are characterised by having radial symmetry as adults, usually five-fold symmetry. In contrast, during their early developmental stages, the larvae have bilateral symmetry. Other characteristics of adults are the possession of a water vascular system and having calcareous skeletons consisting of flat plates connected by a mesh of mutable collagen fibres.[3] Asteroids are characterised by a central disc with a number of radiating arms, typically five. The ossicles that form the hard element of the skeletal structure extend from the disc onto the arms in a continuous arrangement which gives the arms a broad base.[4] This is in contrast to the ophiuroids, in which the disc is clearly separated from the long, slender arms.[5]

Asteroids are poorly represented in the fossil record. This may be because the hard skeletal parts separate as the animal decays or because the soft tissues collapse into distorted, unrecognisable remains. Another reason may be that most asteroids live on hard substrates where conditions are not favourable for fossilisation. The first known asteroids date back to the Ordovician. In the two major extinction events during the late Devonian and late Permian, many species died out, but others survived. These diversified rapidly within a time frame of 60 million years during the Early Jurassic and the early part of the Middle Jurassic.[4]

Diversity

- Brisingida (2 families, 17 genera, 111 species) [6]

- Species in this order have a small, inflexible disc and between six and 20 long, thin arms which they use for suspension feeding. They have a single series of marginal plates, a fused ring of disc plates, no actinal plates, a spool-like ambulacral column, reduced abactinal plates, crossed pedicellariae, and several series of long spines on the arms. They live almost exclusively in deep-sea habitats, although a few live in shallow waters in the Antarctic.[7][8] In some species, the tube feet have rounded tips and lack suckers.[9]

- Forcipulatida (6 families, 63 genera, 269 species) [10]

- Species in this order have distinctive pedicellariae, consisting of a short stalk with three skeletal ossicles. They tend to have robust bodies.[11] They have tube feet with flat-tipped suckers.[9] The order includes well-known common species from temperate regions, as well as cold-water and abyssal species.[12]

- Paxillosida (7 families, 48 genera, 372 species) [13]

- Notomyotida (1 family, 8 genera, 75 species) [15]

- Spinulosida (1 family, 8 genera, 121 species) [17]

- Most species in this order lack pedicellariae and all have a delicate skeletal arrangement with small marginal plates on the disc and arms. They have numerous groups of low spines on the aboral (upper) surface.[18]

- Valvatida (16 families, 172 genera, 695 species) [19]

- Most species in this order have five arms and tube feet. There are conspicuous marginal plates on the arms and disc, and the main pedicellariae are clamp-like.[20]

- Velatida (4 families, 16 genera, 138 species) [21]

- This order of asteroids consists mostly of deep-sea and other cold-water starfish, often with a global distribution. The shape is pentagonal or star-shaped with five to fifteen arms. They mostly have poorly developed skeletons.[22]

Appearance

Starfish are radially symmetric and typically express pentamerism or pentaradial symmetry as adults. However, the evolutionary ancestors of echinoderms are believed to have had bilateral symmetry. Modern starfish, as well as other echinoderms, exhibit bilateral symmetry in their larval forms.[23]

Most starfish typically have five rays or arms, which radiate from a central disc. However, several species frequently have six or more arms. Several asteroid groups, such as the Solasteridae, have 10 to 15 arms, whereas some species, such as the Antarctic Labidiaster annulatus can have up to 50. It is not unusual for species that typically have five rays to exceptionally possess six or more rays due to developmental abnormalities.[24]

The surfaces of starfish bear plate-like calcium carbonate components known as ossicles. These form the endoskeleton, which takes on a number of forms, externally expressed as a variety of structures, such as spines and granules. These may be arranged in patterns or series, and their architecture, individual shapes, and locations are used to classify the different groups within the Asteroidea. Terminology referring to body location in starfish is usually based in reference to the mouth to avoid incorrect assumptions of homology with the dorsal and ventral surfaces in other bilateral animals. The bottom surface is often referred to as the oral or actinal surface, whereas the top surface is referred to as the aboral or abactinal side.[25]

The body surfaces of starfish have several structures that comprise the basic anatomy of the animal and can sometimes assist in its identification. The madreporite can be easily identified as the light-coloured circle, located slightly off centre on the central disc. This porous plate is connected via a calcified channel to the animal's water vascular system in the disc. Its function is, at least in part, to provide additional water for the animal's needs, including replenishing water to the water vascular system.[25] Near the madreporite, also off centre, is the anus. On the oral surface there is an ambulacral groove running down each arm. On either side of this there is a double row of unfused ossicles. The tube feet extend through notches in these and are connected internally to the water vascular system.[25]

Several groups of asteroids, including the Valvatida, but especially the Forcipulatida, possess small, bear-trap or valve-like structures known as pedicellariae. These can occur widely over the body surfaces. In forcipulate asteroids, such as Asterias and Pisaster, pedicellariae occur in pom-pon-like tufts at the base of each spine, whereas in the Goniasteridae, such as Hippasteria phrygiana, pedicellariae are scattered over the body surface. Although the full range of function for these structures is unknown, some are thought to assist in defence, while others have been observed to aid in feeding or in the removal of other organisms attempting to settle on the surface of the starfish.[25] The Antarctic Labidiaster annulatus uses its large pedicellariae to capture active krill prey. The North Pacific Stylasterias forreri has been observed to capture small fish with its pedicellariae.[26]

Other types of structures vary by taxon. For example, members of the family Porcellanasteridae employ additional sieve-like organs which occur among their lateral plate series, which are thought to generate currents in the burrows made by these infaunal starfish.[27]

Internal anatomy

1 – Pyloric stomach 2 – Intestine and anus 3 – Rectal sac 4 – Stone canal 5 – Madreporite 6 – Pyloric caecum 7 – Digestive glands 8 – Cardiac stomach 9 – Gonad 10 – Radial canal 11 – Tube feet

As echinoderms, starfish possess a hydraulic water vascular system that aids in locomotion.[28] This system has many projections called tube feet on the starfish's arms which function in locomotion and aid with feeding. Tube feet emerge through openings in the endoskeleton and are externally expressed through the open grooves present along the oral surface of each arm.[29]

The body cavity also contains the circulatory system, called the hemal system. Hemal channels form rings around the mouth (the oral hemal ring), nearer to the aboral surface and around the digestive system (the gastric hemal ring).[30] A portion of the body cavity, the axial sinus, connects the three rings. Each arm also has hemal channels running next to the gonads.[30] These channels have blind ends with no continuous circulation of the blood.[31]

On the end of each arm is a tiny simple eye, which allows the starfish to perceive the difference between light and darkness. This is useful in the detection of moving objects.[32] Only part of each cell is pigmented (thus a red or black colour), with no cornea or iris. This eye is known as a pigment spot ocellus.[33]

Body wall

The body wall consists of a thin, outer epidermis, a thick dermis formed of connective tissue, and a thin, inner peritoneum, which contains longitudinal and circular muscles. The dermis contains rather loosely organised ossicles (bony plates). Some bear external granules, tubercles, and spines, sometimes organised in definite patterns and some specialised as pedicellariae.[25] There may also be papulae, thin-walled protrusions of the body cavity that reach through the body wall and extend into the surrounding water, which serve a respiratory function.[31] These structures are supported by collagen fibres set at right angles to each other and arranged in a three-dimensional web with the ossicles and papulae in the interstices. This arrangement enables both easy flexion of the arms by the starfish with the rapid onset of stiffness and rigidity required for actions performed under stress.[34]

Digestive system

The mouth of a starfish is located in the centre of the oral surface and opens through a short oesophagus into firstly a cardiac stomach, and then, a second, pyloric stomach. Each arm also contains two pyloric caeca, long, hollow tubes branching outwards from the pyloric stomach. Each pyloric caecum is lined by a series of digestive glands, which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients from the food. A short intestine runs from the upper surface of the pyloric stomach to open at an anus near the centre of the upper body.[35]

Many starfish, such as Astropecten and Luidia, swallow their prey whole, and start to digest it in their stomachs before passing it into the pyloric caeca.[35] However, in a great many species, the cardiac stomach can be everted from the organism's body to engulf and digest food. In these species, the cardiac stomach fetches the prey, and then passes it to the pyloric stomach, which always remains internal. Waste is excreted through the anus on the aboral surface of the body.[30]

Because of this ability to digest food outside its body, the starfish is able to hunt prey much larger than its mouth would otherwise allow. Their diets include clams and oysters, arthropods, small fish and gastropod molluscs. Some starfish are not pure carnivores, and may supplement their diets with algae or organic detritus. Some of these species are grazers, but others trap food particles from the water in sticky mucus strands that can be swept towards the mouth along ciliated grooves.[35]

Nervous system

While starfish lack a centralized brain,[36] their bodies have complex nervous systems which are coordinated by what might be termed a distributed brain. They have a network of interlacing nerves, a nerve plexus, which lies within, as well as below, the skin.[27] The oesophagus is also surrounded by a central nerve ring, which sends radial nerves into each of the arms, often parallel with the branches of the water vascular system. These all connect to form a brain. The ring nerves and radial nerves coordinate the starfish's balance and directional systems.[31]

Although starfish do not have many well-defined sensory inputs, they are sensitive to touch, light, temperature, orientation, and the status of water around them.[37] The tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae found on starfish are sensitive to touch, while eyespots on the ends of the rays are light-sensitive.[38] The tube feet, especially those at the tips of the rays, are also sensitive to chemicals, and this sensitivity is used in locating odour sources such as food.[39]

The eyespots each consist of a mass of ocelli, each consisting of pigmented epithelial cells that respond to light and narrow sensory cells lying between them. Each ocellus is covered by a thick, transparent cuticle that both protects it and acts as a lens. Many starfish also possess individual photoreceptor cells across their bodies and are able to respond to light even when their eyespots are covered.[35]

Locomotion

Starfish move using a water vascular system. Water comes into the system via the madreporite. It is then circulated from the stone canal to the ring canal and into the radial canals. The radial canals carry water to the ampulla (reservoir) portion of tube feet.[32] Each tube foot consists of an internal ampulla and an external podium, or "foot". When the ampulla is squeezed, it forces water into the podium, which expands to contact the substrate. In some circumstances, the tube feet seem to work as levers, but when moving on vertical surfaces, they form a traction system.[40] Although the podium resembles a suction cup in appearance, the gripping action is a function of adhesive chemicals rather than suction. Other chemicals and podial contraction allow for release off the substrate.[32][41]

The tube feet latch on to surfaces and move in a wave, with one body section attaching to the surfaces as another releases. Most starfish cannot move quickly, the leather star (Dermasterias imbricata) managing just 15 cm (6 in) in a minute.[42] Some burrowing species from the genera Astropecten and Luidia have points rather than suckers on their long tube feet and are capable of much more rapid motion, "gliding" across the ocean floor. The sand star (Luidia foliolata) can travel at a rate of 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) per minute.[43]

Respiration and excretion

Respiration occurs mainly through the tube feet and through the papulae that dot the body surface. Oxygen from the water is distributed through the body mainly by the fluid in the main body cavity; the hemal system may also play a minor role.[35]

With no distinct excretory organs, excretion of nitrogenous waste is performed through the tube feet and papulae. The body fluid contains phagocytic cells, coelomocytes, which are also found within the hemal and water vascular systems. These cells engulf waste material, and eventually migrate to the tips of the papulae, where they are ejected into the surrounding water. Some waste may also be excreted by the pyloric glands and voided with the faeces.[35]

Starfish do not appear to have any mechanisms for osmoregulation, and keep their body fluids at the same salt concentration as the surrounding water. Although some species can tolerate relatively low salinity, the lack of an osmoregulation system probably explains why starfish are not found in fresh water or even in estuarine environments.[35]

Secondary metabolites

Various toxins and secondary metabolites have been extracted from several species of starfish. Research into the efficacy of these compounds for possible pharmacological or industrial use occurs worldwide.[44]

Life cycle

Starfish are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction.

Sexual reproduction

Most species of starfish are dioecious, there being separate male and female individuals. These are usually not distinguishable externally, as the gonads cannot be seen, but their sex is apparent when they are spawning. Some species are simultaneous hermaphrodites (producing eggs and sperm at the same time). In a few of these, the same gonad, called an ovotestis,[45] produces both eggs and sperm. Yet other starfish are sequential hermaphrodites, with some species being protandrous. In these, young individuals are males that change sex into females as they grow older, Asterina gibbosa being an example of these. Others are protogynous and change sex during their lives from female to male. In some species, when a large female divides, the smaller individuals produced become males. When they grow big enough, they change back into females.[46]

Each arm contains two gonads, which release gametes through openings called gonoducts, located on the central disc between the arms. Fertilization is external in most species, though a few show internal fertilization. In most species, the buoyant eggs and sperm are simply released into the water (free spawning) and the resulting embryos and larvae live as part of the plankton. In others, the eggs may be stuck to the undersides of rocks to develop.[47] In certain species of starfish, the females brood their eggs – either by simply enveloping them [47] or by holding them in specialised structures. These structures include chambers on their aboral surfaces,[48] the pyloric stomach (Leptasterias tenera)[49] or even the gonads themselves.[45] Those starfish that brood their eggs by covering them usually raise their disc and assume a humped posture.[50] One species broods a few of its young and broadcasts the remaining eggs which cannot fit into the pouch.[48] In these brooding species, the eggs are relatively large, and supplied with yolk, and they generally, but not always,[45] develop directly into miniature starfish without a larval stage. The developing young are called "lecithotrophic" because they get their nutrition from the yolk, as opposed to planktotrophic feeding larvae. In one species of intragonadal brooder, the young starfish obtain their nutrition by eating other eggs and embryos in their gonadal brood pouch.[51] Brooding is especially common in polar and deep-sea species that live in environments less favourable for larval development [35][49] and in smaller species that produce few eggs.[52]

Reproduction occurs at different times of year according to species. To increase the chances of their eggs being fertilized, starfish may synchronize their spawning, aggregating in groups [47] or forming pairs.[53] This latter behaviour is called pseudo-copulation [54] and the male climbs onto the female, placing his arms between hers, and releases sperm into the water. This stimulates her to release her eggs. Starfish may use environmental signals to coordinate the time of spawning (day length to indicate the correct time of the year, dawn or dusk to indicate the correct time of day), and chemical signals to indicate their readiness to each other.[55] In some species, mature females produce chemicals to attract sperm in the sea water.[55]

Asexual reproduction

Some species of starfish also reproduce asexually as adults either by fission[56] of their central discs or by the autotomy of their arms. The type of reproduction depends on the genus. Among starfish that regenerate whole bodies from their arms, some can do so even from fragments just 1 cm long.[57] Single arms that are regenerating the disc and other arms are called comet forms. The division of the starfish either across their discs or at their arms is usually accompanied by changes that help them break easily.[58]

The larvae of several starfish species can also reproduce asexually.[59] They may do this by autotomising some parts of their bodies or by budding.[60] When the larvae sense plentiful food, they favour asexual reproduction instead of directly developing.[61] Though this costs the larvae time and energy, it will allow a single larva to give rise to multiple adults when the conditions are right. Various other reasons trigger similar phenomena in the larvae of other echinoderms. These include the use of tissues that will be lost during metamorphosis or the presence of predators that target larger larvae.[62]

Larval development

Like all echinoderms, starfish are developmentally (embryologically) deuterostomes, a feature they share with chordates (including vertebrates), but not with most other invertebrates. Their embryos initially develop bilateral symmetry, again reflecting their likely common ancestry with chordates. Later development takes a very different path, however, as the developing starfish settle out of the zooplankton and develop the characteristic radial symmetry. As the organisms grow, one side of their bodies grows more than the other, and eventually absorbs the smaller side. After that, the body is formed into five parts around a central axis and the starfish has radial symmetry.[31]

The larvae of starfish are ciliated, free-swimming organisms. Fertilized eggs grow into bipinnaria and (in most cases) later into brachiolaria larvae, which either grow using a yolk or by catching and eating other plankton. In either case, they live as plankton, suspended in the water and swimming by using beating cilia. The larvae are bilaterally symmetric and have distinct left and right sides. Eventually, they settle onto the bottom of the sea, undergo a complete metamorphosis, and grow into adults.[31]

Lifespan

The lifespans of starfish vary considerably between species, generally being longer in larger species. For example, Leptasterias hexactis, with an adult weight of 20 g (0.7 oz) reaches sexual maturity in two years, and lives for about 10 years in total, while Pisaster ochraceus, adult weight 80 g (2.8 oz), reaches maturity in five years and may live to the age of 34.[35]

Regeneration

Some[57] species of starfish have the ability to regenerate lost arms and can regrow an entire new limb given time. Some species can regrow a complete new disc from a single arm,[63] while others need at least part of the central disc to be attached to the detached part.[63] Regrowth can take several months or years.[57][63] Starfish are vulnerable to infections during the early stages after the loss of an arm.[57] A separated limb lives off stored nutrients until it regrows a disc and mouth and is able to feed again. Other than fragmentation carried out for the purpose of reproduction, the division of the body may happen inadvertently due to being detached by a predator, or part may be actively shed by the starfish in an escape response, a process known as autotomy. The loss of parts of the body is achieved by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nervous signals. This type of tissue is called catch connective tissue and is found in most echinoderms.[64][65]

Diet

Most species are generalist predators, eating mollusks such as clams, oysters, some snails, or any other animal too slow to evade their attack (e.g. other echinoderms, or dying fish). Some species are detritivores, eating decomposing animal and plant material or organic films attached to substrates. Others, such as members of the order Brisingida, feed on sponges or plankton and suspended organic particles. The crown-of-thorns starfish consumes coral polyps, and is part of the food chain on reefs. Occasionally, unexplained explosive outbreaks of these starfish occur and may cause major damage to coral reef ecosystems.[66]

The processes of feeding and capture may be aided by special parts; Pisaster brevispinus, the short-spined pisaster from the West Coast of America, may use a set of specialized tube feet to dig itself deep into the soft substrata to extract prey (usually clams).[67] Grasping the shellfish, the starfish slowly pries open the prey's shell by wearing out its adductor muscle, and then inserts its everted stomach into an opening to devour the soft tissues. The gap between the valves need only be a fraction of a millimetre wide for the stomach to gain entry.[32]

Distribution

About 1,600 living species of starfish are known.[68] Echinoderms maintain a delicate internal electrolyte balance in their bodies and this is only possible in a marine environment. This means starfish occur in all of the Earth's oceans, but are not found in any freshwater habitats.[32] The greatest variety of species is found in the tropical Indo-Pacific. Other areas known for their great diversity include the tropical-temperate regions around Australia, the tropical East Pacific and the cold-temperate water of the North Pacific (California to Alaska). All starfish live on the sea bed, but their larvae are planktonic, which allows them to disperse to new locations. Habitats range from tropical coral reefs, rocks, shell brash, gravel, mud, and sand to kelp forests, seagrass meadows and the deep-sea floor.[69]

Threats

Starfish and other echinoderms pump water directly into their bodies via the water vascular system. This makes them vulnerable to all forms of water pollution, as they have little ability to filter out the toxins and contaminants it contains. Oil spills and similar events often take a toll on echinoderm populations that carry far-reaching consequences for the ecosystem.[70]

References

- ^ Sweet, Elizabeth (22 November 2005). "Asterozoa: Fossil groups: SciComms 05-06: Earth Sciences". Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- ^ Mooi, Rich. "Classification of the Extant Echinodermata." California Academy of Sciences – Research.

- ^ Wray, Gregory A. (1999). "Echinodermata: Spiny-skinned animals: sea urchins, starfish, and their allies". Tree of Life web project. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ a b Knott, Emily (2004). "Asteroidea: Sea stars and starfishes". Tree of Life web project. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Stöhr, S.; O’Hara, T. "World Ophiuroidea Database". Retrieved 19 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Brisingida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Downey, Maureen E. (1986). "Revision of the Atlantic Brisingida (Echinodermata: Asteroidea), with Description of a New Genus and Family" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology: 435. Smithsonian Institution Press. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Brisingida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Vickery, Minako S.; McClintock, James B. (2000). "Comparative Morphology of Tube Feet Among the Asteroidea: Phylogenetic Implications". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 40 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1093/icb/40.3.355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Forcipulatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 948. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Mah, Christopher. "Forcipulatida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Paxillosida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Matsubara, M.; Komatsu, M.; Araki, T.; Asakawa, S.; Yokobori, S.-I.; Watanabe, K.; Wada, H. (2005) The phylogenetic status of Paxillosida (Asteroidea) based on complete mitochondrial DNA sequences. Molecular Genetics and Evolution, 36, 598–605

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Notomyotida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Asterozoa: Fossil groups: SciComms 05-06: Earth Sciences". Palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk. 22 November 2005. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Spinulosida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Spinulosida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Valvatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Blake, DanielB. (1981). "A reassessment of the sea-star orders Valvatida and Spinulosida". Journal of Natural History. 15 (3): 375–394. doi:10.1080/00222938100770291.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (2012). "Velatida". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher. "Velatida". Access Science: Encyclopedia. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Starfish." 16 May 2008. HowStuffWorks.com. 16 January 2009.

- ^ You superstar! Fisherman hauls in starfish with eight legs instead of five, Daily Mail, 24 October 2009, accessed 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Barnes, R. S. K. (1988). The Invertebrates: a new synthesis. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0-632-03125-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Chia, Fu-Shiang; Amerongen, Helen (1975). "On the prey-catching pedicellariae of a starfish, Stylasterias forreri (de Loriol)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 53 (6): 748–755. doi:10.1139/z75-089.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Star Fish" South Central Service Co-op. 2001

- ^ "Wonders of the Sea: Echinoderms." Ceanside Meadows Institute for the Arts and Sciences.

- ^ Walls, Jerry G. (1982). Encyclopedia of Marine Invertebrates. TFH Publications. pp. 681–684. ISBN 0-86622-141-7.

- ^ a b c Dale, Jonathan (2000). "Starfish Digestion and Circulation". Madreporite Nexus. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Richard Fox. "Asterias forbesi". Invertebrate Anatomy OnLine. Lander University. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Dorit, R. L. (1991). Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. p. 782. ISBN 0-03-030504-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Bioscience. McGraw-Hill Professional. 2004. p. 790. ISBN 0071439560.

- ^ O'Neill P. (1989). "Structure and mechanics of starfish body wall". Journal of Experimental Biology. 147: 53–89. PMID 2614339.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 939–945. ISBN 0-03-056747-5. Cite error: The named reference "IZ" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Starfish Facts, by Robert Cheney Ocean Facts and FAQ "...They do not have a centralized brain...", accessed March 17, 2013

- ^ Holladay, April (18 April 2008). ""Brainless" sea stars have brains". WonderQuest. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Dale, Jonathan. "Why Do Starfish Always Have Five Rays?" Madreporite Nexus. 24 May 2009.

- ^ Dale, Jonathan (9 November 2001). "Chemosensory Orientation in Asterias forbesi". Madreporite Nexus. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Kerkut, G. A. (1953). "The Forces Exerted by the Tube Feet of the Starfish During Locomotion". Journal of Experimental Biology. 30: 575–583.

- ^ Cavey, Michaelj.; Wood, Richardl. (1981). "Specializations for excitation-contraction coupling in the podial retractor cells of the starfish Stylasterias forreri". Cell and Tissue Research. 218 (3). doi:10.1007/BF00210108.

- ^ "Leather star - Dermasterias imbricata". Sea Stars of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Sand star - Luidia foliolata". Sea Stars of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ Zhang, Wen; Guo, Yue-Wei; Gu, Yucheng (2006). "Secondary Metabolites from the South China Sea Invertebrates: Chemistry and Biological Activity". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (17): 2041–2090. doi:10.2174/092986706777584960.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Byrne, Maria (2005). "Viviparity in the Sea Star Cryptasterina hystera (Asterinidae)--Conserved and Modified Features in Reproduction and Development". Biol Bull. 208 (2): 81–91. doi:10.2307/3593116. PMID 15837957.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Ottesen, P. O. (1982). "Divide or broadcast: Interrelation of asexual and sexual reproduction in a population of the fissiparous hermaphroditic seastar Nepanthia belcheri (Asteroidea: Asterinidae)". Marine Biology. 69 (3): 223–233. doi:10.1007/BF00397488. ISSN 0025-3162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Crump, R.G (1983). "The natural history, life history and ecology of the two British species of Asterina" (PDF). Field Stydies. 5: 867–882. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b McClary, D. J. (1989-12). "Reproductive pattern in the brooding and broadcasting sea star Pteraster militaris". Marine Biology. 103 (4): 531–540. doi:10.1007/BF00399585. ISSN 0025-3162.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gordon Hendler and David R. Franz (1982). "The Biology of a Brooding Seastar, Leptasterias tenera, in Block Island" (Free full text). Biol Bull. 162 (3): 273–289. doi:10.2307/1540983. JSTOR 1540983.

- ^ Fu-Shiang Chia (1966). "Brooding Behavior of a Six-Rayed Starfish, Leptasterias hexactis" (Free full text). Biol Bull. 130 (3): 304–315. doi:10.2307/1539738. JSTOR 1539738.

- ^ Byrne, M. (1996). "Viviparity and intragonadal cannibalism in the diminutive sea stars Patiriella vivipara and P. parvivipara (family Asterinidae)". Marine Biology. 125 (3): 551–567. ISSN 0025-3162.

- ^ Strathmann, Richard R. (1 June 1984). "Does Limited Brood Capacity Link Adult Size, Brooding, and Simultaneous Hermaphroditism? A Test with the Starfish Asterina phylactica". The American Naturalist. 123 (6): 796–818. doi:10.1086/284240. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2460901.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Run, J. -Q. (1988). "Mating behaviour and reproductive cycle of Archaster typicus (Echinodermata: Asteroidea)". Marine Biology. 99 (2): 247–253. doi:10.1007/BF00391987. ISSN 0025-3162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Keesing, John K. (2011). "Synchronous aggregated pseudo-copulation of the sea star Archaster angulatus Müller & Troschel, 1842 (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) and its reproductive cycle in south-western Australia". Marine Biology. 158 (5): 1163–1173. doi:10.1007/s00227-011-1638-2. ISSN 0025-3162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Miller, Richard L. (12 October 1989). "Evidence for the presence of sexual pheromones in free-spawning starfish". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 130 (3): 205–221. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(89)90164-0. ISSN 0022-0981.

- ^ Fisher, W. K. (1 March 1925). "Asexual Reproduction in the Starfish, Sclerasterias" (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 48 (3): 171–175. doi:10.2307/1536659. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1536659. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Edmondson, C.H (1935). "Autonomy and regeneration of Hawaiian starfishes" (PDF). Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. 11 (8): 3–20.

- ^ Monks, Sarah P. (1 April 1904). "Variability and Autotomy of Phataria". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 56 (2): 596–600. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4063000.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Eaves, Alexandra A. (2003). "Reproduction: Widespread cloning in echinoderm larvae". Nature. 425 (6954): 146. doi:10.1038/425146a. ISSN 0028-0836.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jaeckle, William B. (1 February 1994). "Multiple Modes of Asexual Reproduction by Tropical and Subtropical Sea Star Larvae: An Unusual Adaptation for Genet Dispersal and Survival" (Free full text). Biological Bulletin. 186 (1): 62–71. doi:10.2307/1542036. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1542036.

- ^ Vickery, M. S. (1 December 2000). "Effects of Food Concentration and Availability on the Incidence of Cloning in Planktotrophic Larvae of the Sea Star Pisaster ochraceus". The Biological Bulletin. 199 (3): 298–304. ISSN 1939-8697 0006-3185, 1939-8697.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Knaack, Lauren; Jaeckel, William (2011). "Incidence of larval cloning in the sea urchins Arbacia punctulata and Lytechinus variegatus". John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c McAlary, Florence A. (1993). Population Structure and Reproduction of the Fissiparous Seastar, Linckia columbiae Gray, on Santa Catalina Island, California. 3rd California Islands Symposium. National Park Service. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Mladenov, Philip V (1 April 1989). "Purification and Partial Characterization of an Autotomy-Promoting Factor from the Sea Star Pycnopodia Helianthoides". The Biological Bulletin. 176 (2): 169–175. ISSN 1939-8697 0006-3185, 1939-8697.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hayashi, Yutaka (1 September 1986). "Effects of Ionic Environment on Viscosity of Catch Connective Tissue in Holothurian Body Wall". Journal of Experimental Biology. 125 (1): 71–84. ISSN 1477-9145 0022-0949, 1477-9145.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dale, Jonathan. "Starfish Ecology." Madreporite Nexus. 24 May 2009.

- ^ Nybakken Marine Biology: An Ecological Approach, Fourth Edition, page 174. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc., 1997.

- ^ "Sea star". Encyclopedia Brittanica online. Encyclopedia Brittanica. 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ "Asteroidea (Sea Stars)". Encyclopedia.com. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ Mah, Christopher (6 September 2009). "The Invisible Loss: The Impacts of Oil You Do Not See". The Ocean Portal. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

Further reading

- Blake DB, Guensburg TE; Implications of a new early Ordovician asteroid (Echinodermata) for the phylogeny of Asterozoans; Journal of Paleontology, 79 (2): 395–399; MAR 2005.

- Gilbertson, Lance; Zoology Lab Manual; McGraw Hill Companies, New York; ISBN 0-07-237716-X (fourth edition, 1999).

- Shackleton, Juliette D.; Skeletal homologies, phylogeny and classification of the earliest asterozoan echinoderms; Journal of Systematic Palaeontology; 3 (1): 29–114; March 2005.

- Solomon, E.P., Berg, L.R., Martin, D.W. 2002. Biology, Sixth Edition.

- Sutton MD, Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Gladwell DJ; A starfish with three-dimensionally preserved soft parts from the Silurian of England; Proceedings of the Royal Society B – Biological Sciences; 272 (1567): 1001–1006; MAY 22 2005.

- Hickman C.P, Roberts L.S, Larson A., l'Anson H., Eisenhour D.J.; Integrated Principles of Zoology; McGraw Hill; New York; ISBN 0-07-111593-5 (Thirteenth edition; 2006).