The Mamas & the Papas

The Mamas and the Papas | |

|---|---|

From left: Michelle Phillips, Cass Elliot, Denny Doherty and John Phillips on the Ed Sullivan Show, 1967. | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | New York City, United States |

| Genres | Folk rock, psychedelic pop, sunshine pop |

| Years active | 1965–1968, 1971 |

| Labels | Dunhill |

| Past members | Denny Doherty Cass Elliot John Phillips Michelle Phillips Jill Gibson |

The Mamas & the Papas were an American folk rock vocal group that recorded and performed from 1965 to 1968, reuniting briefly in 1971. They released five studio albums and seventeen singles, six of which made the top ten, and sold close to 40 million records worldwide.[1] The group was composed of John Phillips (1935–2001), Canadian Denny Doherty (1940–2007), Cass Elliot (1941–1974), and Michelle Phillips née Gilliam (b. 1944). Their sound was based on vocal harmonies arranged by John Phillips,[2] the songwriter, musician, and leader of the group who adapted folk to the new beat style of the early sixties.

Formation

The group was formed by husband and wife John and Michelle Phillips, formerly of The New Journeymen, and Denny Doherty, formerly of The Mugwumps. Both of these earlier acts were folk groups active from 1964 to 1965. The last member to join was Cass Elliot, Doherty's bandmate in The Mugwumps, who had to overcome John Phillips' concern that her voice was too low for his arrangements, that her physical appearance would be an obstacle to the band's success, and that her temperament was incompatible with his.[3] The group considered calling itself The Magic Circle before switching to The Mamas and the Papas, apparently inspired by the Hells Angels, whose female associates were called "mamas".[4][5][6]

The quartet spent the period from early spring to midsummer 1965 in the Virgin Islands "to rehearse and just put everything together", as John Phillips later recalled.[7] Phillips acknowledged that he was reluctant to abandon folk music.[8] Others have said he hung on to it "like death".[9] Roger McGuinn's more measured view is that "It was hard for John to break out of folk music, because I think he was real good at it, conservative, and successful, too."[10] Phillips also acknowledged that it was Doherty and Elliot who awakened him to the potential of contemporary pop, as epitomized by the Beatles – the New Journeymen had played acoustic folk, with banjo; The Mugwumps played something closer to folk rock, with bass and drums.[11][12] Their rehearsals in the Virgin Islands were "the first time that we tried playing electric".[13][14]

The band then traveled from New York to Los Angeles for an audition with Lou Adler, co-owner of Dunhill Records. The audition was arranged by Barry McGuire, who had befriended Cass Elliot and John Phillips independently over the previous two years, and who had recently signed with Dunhill himself.[15][16][17] It led to "a deal in which they would record two albums a year for the next five years", with a royalty of 5 per cent on 90 per cent of retail sales.[18][19] Dunhill also tied the band to management and publishing deals, creating an obvious conflict of interest, although the practice was not unusual at the time.[20][21] Cass Elliot's membership was not formalized until the paperwork was signed, with Adler, Michelle Phillips, and Doherty overruling John Phillips.[22]

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears

The Mamas and the Papas made their inaugural recording singing backing vocals on McGuire's album This Precious Time, although they had already released a single of their own by the time the album appeared in December 1965.[23] This was "Go Where You Wanna Go", which was given a limited release in November and failed to chart.[24] There are few copies of this single extant and the follow-up, "California Dreamin'", has the same B-side, suggesting that "Go Where You Wanna Go" had been withdrawn.[25][26] "California Dreamin'" was released in December, supported by a full-page ad in Billboard on the 18th of that month.[27] It peaked at number four in the United States and number twenty-three in the United Kingdom.

The quartet's debut album, If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears, followed in February 1966 and became its only number-one on the Billboard 200. The third and final single from the album, "Monday, Monday",[2] was released in March 1966. It became the band's only number-one hit in the US, reached number three in the UK, and was the first number-one on Spain's new Los 40 Principales. "Monday, Monday" won the Grammy Award for Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals in 1967. It was also nominated for Best Performance by a Vocal Group, Best Contemporary Song, and Record of the Year.

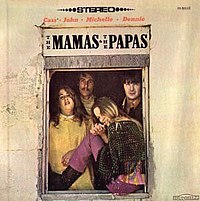

The Mamas and the Papas

Their second album, The Mamas and the Papas, is sometimes referred to as Cass, John, Michelle, Dennie, whose names appear thus above the band's name on the cover. Recording was interrupted when Michelle Phillips became indiscreet about her affair with Gene Clark of The Byrds.[28][29] A liaison the previous year between Michelle Phillips and Denny Doherty had been forgiven; Doherty and John Phillips had reconciled and written "I Saw Her Again" about the episode,[30][31] although they later disagreed on how much Doherty contributed to the song.[32] This time, Phillips was determined to fire his wife.[33] After consulting their attorney and record label, he, Elliot, and Doherty served Michelle Phillips with a letter expelling her from the group on June 28, 1966.[34]

Jill Gibson was hired to replace Phillips. Gibson was a visual artist and singer-songwriter who had recorded with Jan and Dean.[35] After being introduced to the band by its producer, Lou Adler, she was soon taking part in concerts (at Forest Hills, New York, Denver, Colorado, and Phoenix, Arizona)[36] television appearances (Hollywood Palace on ABC), and recording sessions.[37] While Gibson was a quick study and well regarded, the three original members concluded that she lacked her predecessor's "stage charisma and grittier edge", and Michelle Phillips was reinstated on August 23, 1966.[38][39] "Jill Gibson, so nearly a full-time Mama, left and was paid a lump sum from the group's funds."[40]

It remains unclear whose vocals appear on The Mamas and the Papas as released on August 30, 1966. Gibson says she sang all but two songs.[41] Studio documents appear to show that Michelle Phillips had already recorded six songs for the album in April 1966, including the singles "I Saw Her Again" and "Words of Love".[42] Lou Adler has said, "We recorded Jill on six songs ... got six vocal performances out of her, which we later replaced, some of 'em."[43] Michelle Phillips has said that she does not know who is singing on the album: "There's no way to know who sang on what, because we both sang on all the parts, and it was up to Bones [Howe] and Lou [Adler] and John [Phillips] what was in the final mix. And they had a lot to choose from! When you listen to the second album ... listen to it ... because I swear I don't have any idea who's singing on it."[41]

The Mamas and the Papas peaked at number four in the US, continuing the band's success, but only made number twenty-four in the UK.

"I Saw Her Again" was released as a single in June 1966 and reached number five in the US and number eleven in the UK. There is a false start to the final chorus of the song. While mixing the record, Bones Howe inadvertently punched in the coda vocals too early. He then rewound the tape and inserted the vocals in their proper position. On playback, the mistaken early entry could still be heard, making it sound as though Doherty repeated the first three words, singing "I saw her ... I saw her again last night". Lou Adler liked the effect, and told Howe to leave it in the final mix.[44] "That has to be a mistake: nobody's that clever," Paul McCartney told the group.[45] The device was imitated by John Sebastian in the Lovin' Spoonful song, "Darlin' Be Home Soon" (1966), and by Kenny Loggins in the song "I'm Alright" (1980).

"Words of Love" was the second single from the album, appearing in November 1966. In the US it was released as a double A-side with "Dancing in the Street" and reached number five ("Dancing in the Street," which had been a hit two years earlier for Martha and the Vandellas, struggled to number seventy-three). In the UK it was backed with "I Can't Wait" and peaked at number forty-seven.

Deliver

The band started work immediately on its third album, Deliver, which was recorded in the autumn of 1966. The first single from the album, "Look Through My Window", was released in September 1966 (before the last single from The Mamas and the Papas). It reached number twenty-four in the US, but did not chart in the UK. The second single, "Dedicated to the One I Love" (February 1967), did much better, peaking at number two in both the US and the UK. That success helped the album, also released in February 1967, reach number two in the US and number four in the UK. The third single, "Creeque Alley" (April 1967), chronicled the band's early history. It peaked at number five in the US and number nine in the UK.

The strain on the group was apparent when they performed indifferently at the first Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, as can be heard on Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International Pop Festival (1970). The band was badly under-rehearsed – partly because John and Michelle Phillips and Lou Adler were preoccupied with organizing the festival, partly because Doherty arrived at the last minute from another sojourn in the Virgin Islands,[46][47][48] and partly, it is said, because he was drinking heavily in the aftermath of his affair with Michelle Phillips.[49] They rallied for their performance before 18,000 people at the Hollywood Bowl in August (with Jimi Hendrix as the opener), which both John and Michelle Phillips would remember as the apex of the band's career: "There would never be anything quite like it again."[50]

Deliver was followed in October 1967 by the non-album single "Glad to Be Unhappy", which reached number twenty-six in the US. "Dancing Bear" from the group's second album was released as a single in November. It peaked at number fifty-one in the US. Neither of these singles charted in the UK.

The Papas and the Mamas

The Mamas and the Papas cut their first three albums at United Western Recorders in Hollywood.[51] The last two were recorded at the eight-track studio John and Michelle Phillips built at their home in Bel Air – this at a time when four-track recording was still the norm.[52][53] John Phillips said, "I got the idea to transform the attic into my own recording studio, so I could stay high all the time and never have to worry about studio time. I began assembling the state-of-the-art equipment and ran the cost up to about a hundred grand."[54]

While this gave him the autonomy he craved, it also removed the external discipline that may have been beneficial to a man who described himself as an "obsessive perfectionist".[55] Doherty, Elliot, and Adler all found the arrangement uncongenial, with Elliot later complaining to Rolling Stone (October 26, 1968): "We spent one whole month on one song, just the vocals for 'The Love of Ivy' took one whole month. I did my [debut solo] album in three weeks, a total of ten days in the studio. Live with the band, not prerecorded tracks sitting there with earphones."[56] The recording sessions for the fourth album eventually stalled completely, and in September 1967 John Phillips called a press conference to announce that The Mamas and the Papas were taking a break, which they confirmed on the Ed Sullivan Show on the 24th of that month.[57][58][59]

The plan was to give concerts at the Royal Albert Hall in London and the Olympia in Paris before taking time out on Majorca to "get the muse going again", as John Phillips put it.[60][61] When they docked at Southampton on October 5, Elliot was arrested on a charge of stealing two blankets and a hotel key worth ten guineas (US$28) when she was in England the previous February. Elliot was transferred to London, strip-searched, and spent a night in custody before the case was dismissed in the West London Magistrates' Court the next day.[62] The hotel was less interested in the blankets than in an unpaid bill; it transpired that Elliot had entrusted the money to her companion, Pic Dawson (1943–1986),[63] who neglected to settle the account.[64] The police were less interested in the blankets or the bill than in Dawson, who was suspected of international drug trafficking, and was "the sole subject" of their questioning.[65]

Later, at a party hosted by the band to celebrate her acquittal, John Phillips interrupted Elliot as she was telling Mick Jagger about her arrest and trial: "Mick, she's got it all wrong, that's not how it was at all." Elliot "screamed" at Phillips "before storming out of the room".[66][67] Elliot was ready to quit, the Royal Albert Hall and Olympia dates were cancelled, and the four went their separate ways: John and Michelle Phillips to Morocco; Doherty back to the United States; and Elliot either back to the United States (according to John Phillips) or to a rendezvous in Paris with Pic Dawson (according to Michelle Phillips).[67][68] In an interview with Melody Maker, Elliot unilaterally announced that The Mamas and the Papas had disbanded: "We thought this trip would give the group some stimulation, but this has not been so."[69]

In fact, Phillips and Elliot patched things up sufficiently to complete The Papas and the Mamas, which was released in May 1968. It was relatively successful in both the UK and US, although it was their first not to go gold or reach the top ten in America. "12:30 (Young Girls Are Coming to the Canyon)" had been released as a single in August 1967;[2] it peaked at number twenty in the US, but failed to chart in the UK. After the second single, "Safe in My Garden" (May 1968), made it only to number fifty-three, Dunhill released Elliot's solo feature from the album, a cover of "Dream a Little Dream of Me", as a single credited to "Mama Cass with the Mamas and the Papas" in June 1968 – against John Phillips' wishes.[70] It reached number twelve in the US and became the band's first single to chart in the UK after five failures, peaking at number eleven. It was the only Mamas and Papas single to chart higher in the UK than in the US. The fourth and final single from The Papas and the Mamas was "For the Love of Ivy" (July 1968), which peaked at number eighty-one in the US and did not chart in the UK. For the second time, Dunhill returned to their earlier work for a single. In this case it was "Do You Wanna Dance" from the debut album, released as a single in October 1968. It failed to chart in the UK and reached number seventy-six in the US.

Break-up and People Like Us

The success of "Dream a Little Dream of Me" confirmed Elliot's desire to embark on a solo career, and by the end of 1968 it appeared that the band had split. Its chart performance had become increasingly erratic, with three of its last four singles failing on both sides of the Atlantic. As John Phillips recalled, "Times had changed. The Beatles showed the way. Music itself was heading toward a technological and compositional complexity that would leave many of us behind. It was tough to keep up."[71] The group "made it official" at the beginning of 1969: "Dunhill released us from our contracts and we were history, though we still owed the label another album."[72] Elliot (billed as Mama Cass) had released her solo debut Dream a Little Dream in 1968, Phillips released John Phillips (John, the Wolf King of L.A.) in 1970, and Denny Doherty followed with Watcha Gonna Do? in 1971.

Dunhill maintained momentum by releasing The Best of the Mamas and the Papas: Farewell to the First Golden Era in 1967, Golden Era Vol. 2 in 1968, 16 of Their Greatest Hits in 1969, and the Monterey live album in 1970. It was also determined to get the promised last LP, for which it had given the band an extension until September 1971.[73] It warned that each member of the group would be sued for $250,000 if they did not deliver (about $1.4 million apiece in 2010 values).[74] John Phillips wrote another collection of songs, which was arranged, rehearsed, and recorded in fits and starts over about a year, depending on the availability of the other group members: "It was rare we were all together. Most tracks were dubbed, one vocal at a time."[75] The Mamas and the Papas' last album of new material, People Like Us, was released in November 1971. The only single, "Step Out" (January 1972), reached number eighty-one in the US. The album peaked at number eighty-four on the Billboard 200, making it the only Mamas and Papas LP not to reach the top twenty in the US. Neither single nor album charted in the UK. Contractual obligations fulfilled, the band's split was now final.

Aftermath

Cass Elliot

Cass Elliot had a successful solo career, touring the U.S. and Europe; appearing frequently on television, including in two specials (The Mama Cass Television Program on ABC in January 1969 and Don't Call Me Mama Anymore on CBS in September 1973); and producing hits such as "Make Your Own Kind of Music" and "It's Getting Better". That said, she never surpassed her two Dunhill albums, Dream a Little Dream (1968) and Bubblegum, Lemonade, and ... Something for Mama (1969). None of the three albums she recorded for RCA – Cass Elliot (1972), The Road Is No Place for a Lady (1972), and Don't Call Me Mama Anymore (1973) – produced a charting single.

Elliot died of heart failure in London on July 29, 1974, after completing a two-week engagement at the Palladium. The shows were mostly sold out and prompted standing ovations. Her former bandmates and Lou Adler attended her funeral in Los Angeles. Elliot was survived by her only child, Owen Vanessa Elliot (b. 1967).

John Phillips

John Phillips' country-influenced solo album, John Phillips (John, the Wolf King of L.A.), was not a commercial success, despite featuring the single "Mississippi", which reached number thirty-two in the US. Nevertheless, it continues to enjoy critical favor. Rolling Stone gave it four stars when it was reissued in 2006, calling it “a genuine lost treasure”.[76] Denny Doherty said that if the Mamas and the Papas had recorded the album, it might have been their best.[77] Phillips wrote songs for the soundtrack to Brewster McCloud (Robert Altman, 1970)[78] and original music for the soundtracks to Myra Breckinridge (Michael Sarne,1970)[79] and The Man Who Fell to Earth (Nicholas Roeg, 1976).[80] He also wrote the ill-fated stage musical Man on the Moon (1975) and songs with and for other artists, including most of the tracks on the album Romance Is on the Rise (1974) by his then wife Geneviève Waïte, which he also produced;[81] and "Kokomo" (1988), which was a number-one hit for the Beach Boys.

Phillips was lost to heroin addiction through much of the 1970s, a period that culminated in his arrest and conviction in 1980 on a charge of conspiring to distribute narcotics, for which he spent a month in jail in 1981.[82][83][84] In later years he performed with the New Mamas and the Papas (see below) and appeared in revival shows and television specials. He told his side of the Mamas and Papas' story in the memoir Papa John (1986),[85] and in the PBS television documentary, Straight Shooter: The True Story of John Phillips and the Mamas and the Papas (1988).[86] John Phillips died of heart failure in Los Angeles on March 18, 2001.[87]

Two albums were released immediately after his death: Pay Pack and Follow (April 2001), which included material recorded in London and New York with members of the Rolling Stones in 1976 and 1977;[88][89] and Phillips 66 (August 2001), an album of new material and reworkings that "takes its title from the age Phillips would have been when the album was originally slated for its release".[90] A later archival series on Varèse Sarabande included a reissue of John Phillips (John, the Wolf King of L.A.) with bonus tracks (2006); the sessions he recorded for Columbia with the Crusaders in 1972 and 1973, released as Jack of Diamonds (2007);[91] his preferred mix of the Rolling Stones sessions, released with other material as Pussycat (2008);[92] and his demos for Man on the Moon, released as Andy Warhol Presents Man on the Moon: The John Phillips Space Musical (2009).[93]

Phillips had five children: the businessman Jeffrey Phillips (b. 1957) and the actor and singer Laura Mackenzie Phillips (b. 1959) by his first wife Susan Adams; the singer Chynna Gilliam Phillips (b. 1968) of the band Wilson Phillips by his second wife Michelle Gilliam; and the songwriter Tamerlane Orlando Phillips (b. 1971) and the actor and model Bijou Phillips (b. 1980) by his third wife Geneviève Waïte. In 2009, Mackenzie Phillips wrote in her memoir, High on Arrival, that she had been in a long-term sexual relationship with her late father.[94][95]

Denny Doherty

Denny Doherty's solo career faltered after the appearance of Whatcha Gonna Do? in 1971. The follow-up, Waiting for a Song (1974), was not released in the US, although a 2001 reissue by Varèse Sarabande gained wider distribution and the album is now available as a digital download. It features Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot as backing vocalists, the latter in what proved to be her last recorded performances. A single from the album, "You'll Never Know", made the adult contemporary charts. Doherty then turned to the stage, making a disastrous start in John Phillips’ Man on the Moon (1975). In 1977, he returned to his birthplace, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and started playing legitimate roles, including Shakespeare, at the Neptune Theater under the tutelage of John Neville.[96][97] This led to television work, beginning with a variety program, Denny's Sho*, which ran for one season in 1978. He went on to host and voice parts in the children's program, Theodore Tugboat, and to act in various series, including twenty-two episodes of the drama Pit Pony.[98] Doherty also performed with the New Mamas and the Papas (see below). An alcoholic through the 1960s and 1970s, Doherty recovered in the early 1980s and stayed sober for the remainder of his life.[99][100] In 1996, he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.[96]

Doherty answered John Phillips' PBS documentary with the autobiographical stage musical Dream a Little Dream (the Nearly True Story of the Mamas and the Papas), which he wrote with Paul Ledoux and performed sporadically, starting in Halifax in 1997,[101] and eventually reaching the off-Broadway Village Theater in New York in 2003.[102] The original cast recording – featuring Doherty and supporting band – was released by Lewlacow in 1999.[103]

Doherty died of an abdominal aortic aneurysm at his home in Mississauga, Ontario, on January 19, 2007.[104] He was survived by his three children, Jessica Woods, Emberly Doherty, and John Doherty. A documentary by Paul Ledoux, Here I Am: Denny Doherty and the Mamas and the Papas, premiered at Halifax's Atlantic Film Festival in September 2009 and screened on the Bravo cable network as part of the Great Canadian Biographies series in February 2010.[105][106]

Michelle Phillips

While Michelle Phillips' only solo album, Victim of Romance (1977), made little impact, she went on to build a successful career as an actress. Her film credits include The Last Movie (1971), Dillinger (1973), Valentino (1977), Bloodline (1979), The Man with Bogart's Face (1980), American Anthem (1986), Let It Ride (1989), and Joshua Tree (1993). Her television credits include Hotel, Knots Landing, Beverly Hills, 90210, and many others.[107]

Phillips published a memoir, California Dreamin', in 1986,[108] the same year John Phillips published his. Reading the two books together was, according to one reviewer, "like reading the transcripts in a divorce trial."[109] As the co-writer and owner of the copyright to California Dreamin', Phillips was an important contributor to the 2005 PBS television documentary California Dreamin': The Songs of the Mamas and the Papas.[110]

The New Mamas and the Papas

The New Mamas and the Papas were a byproduct of John Phillips' desire to "round out the picture of reform" as he awaited sentencing on narcotics charges in 1980.[111] He invited his children Jeffrey and Mackenzie, both drug addicts living in Los Angeles, and Denny Doherty, an alcoholic living in Canada, to join him at the Fair Oaks Hospital in Summit, New Jersey, where he was undergoing rehabilitation. The children arrived around Thanksgiving and Doherty around Christmas. The idea of reviving the group was born at this time, with Phillips and Doherty in their original roles, Mackenzie Phillips taking Michelle Phillips' part and Elaine "Spanky" McFarlane of Spanky and Our Gang taking the part of Cass Elliot.[112] Little progress was made until after Phillips had been sentenced and served his time in jail. The quartet began rehearsing in earnest and recording demos in the summer of 1981. Their first performances were in March 1982, when they were praised for their "verve and expertise", the "impressive precision" of the harmonies, and the "feeling ... of genuine celebration" on stage.[113]

The group toured the United States, including residencies in Las Vegas and Atlantic City, but lost $150,000 in their first eighteen months. Phillips called a halt in August 1983 and the New Mamas and the Papas did not perform again until February 1985.[114] They then resumed touring, with concerts in Europe, East Asia, and South America, as well as in Canada and the United States; at their height, they were playing up to 280 nights a year.[115] John Phillips stayed off heroin, but remained addicted to alcohol, cocaine, and pills, as did his daughter. This affected the group's performance, as they were occasionally booed off stage.[116]

Doherty quit in 1987 and was replaced by Scott McKenzie (1939–2012). In 1991, Mackenzie Phillips was replaced by Laurie Beebe Lewis,[117] a former vocalist with the Buckinghams who had earlier (1986-1987) temped with the band when Mackenzie Phillips was pregnant. John Phillips dropped out after a liver transplant in 1992 and Doherty returned. Lewis and McFarlane left in 1993, to be replaced by Lisa Brescia and Deb Lyons. The band continued to perform with varying line-ups, including Barry McGuire (1997-1998) and the recovering Phillips, until 1998, by which time, according to one critic, "the jingle singers who sang those fabulous Cass, Michelle, John, and Denny parts were an aural cartoon".[118] In 1998 the lineup was Phillips, Scott McKenzie, Chrissy Faith, David Baker and Janelle Sadler. After Phillips and McKenzie retired permanently from touring, another singer, Mark Williamson, was brought in.

Phillips wanted the New Mamas and the Papas to make an album, "but I just couldn't bring myself to commit to it".[119][120] Varèse Sarabande released the 1981 demos with other material as Many Mamas, Many Papas in 2010. Beyond that, the band is represented on record only by live albums of uncertain provenance, including The Mamas and the Papas Reunion Live (1987) featuring the Phillips-Doherty-Phillips-McFarlane line-up and released by Teichiku in Japan;[103] and Dreamin' Live (2005) on a label called Legacy (not the Columbia-Sony imprint), which features John and Mackenzie Phillips, Spanky McFarlane, and (probably) Scott McKenzie.[121]

Later recognition

In 1986, John and Michelle Phillips were featured in the music video for The Beach Boys' second recording of "California Dreamin'", which appeared on the album Made in U.S.A. Denny Doherty was unavailable. The Mamas and the Papas' own version of "California Dreamin'" was reissued in the UK and peaked at number nine in 1997. The song received a Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 2001.

The Mamas and the Papas were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998, the Vocal Group Hall of Fame in 2000, and the Hit Parade Hall of Fame in 2009. Cass Elliot and Michelle Phillips, as "The Mamas", were ranked number twenty-one on the VH1 network's list of the 100 Greatest Women of Rock.

In a review by Matthew Greenwald, he stated, "One of the best anthologies of the Mamas & the Papas, A Gathering of Flowers was put together immediately after the group's demise, and gives the listener an excellent overview of one of the most revolutionary and appealing groups to emerge from the folk-rock era. Although it may seem slim at first, with only 20 tracks spread out over two LPs, there is much more to be found. In between most cuts there are not only rehearsals and outtakes, but also interview snippets from John Phillips and Cass Elliot. These interviews create an aural documentary of the group in between great cuts like "California Dreamin'," "Monday, Monday," "I Saw Her Again," and others. Excellent liner notes by Andy Wickham and a generous collection of rare photos top this collection off in grand style." This anthology was never produced on CD but was available on vinyl and cassette tape for many years. Some companies are offering a CDR ripped version of this engaging look into the history of the Mamas & the Papas, normally including the source material to preserve copyrights.

The band finally received a box set when the four-CD Complete Anthology was released in the UK in September 2004 and in the US in January 2005. It contains the five studio albums, the live album from Monterey, selections from their solo work, and rarities including their first sessions with Barry McGuire, all in "uniformly excellent" sound.[122] The BBC called it "a treasure chest of pop gold".[123]

In addition to the three documentaries (Straight Shooter, California Dreamin', and Here I Am), Doherty's musical, and the memoirs by John, Michelle, and Mackenzie Phillips, the group is the subject of Doug Hall's The Mamas and the Papas: California Dreamin' (2000)[124] and Matthew Greenwald's Go Where You Wanna Go: The Oral History of the Mamas and the Papas (2002).[125] Cass Elliot is the subject of Jon Johnson's Make Your Own Kind of Music: A Career Retrospective of Cass Elliot (1987)[126] and Eddi Fiegel's Dream a Little Dream of Me: The Life of Mama Cass Elliot (2005).[127] John Phillips' estate has authorized Chris Campion to write a biography of the group's leader, provisionally called Wolfking.[128][129][130]

Fox acquired the rights to make a film about the Mamas and the Papas in 2000.[131] It was reported in 2007 that "The right script is in the process of being written."[132] Peter Fitzpatrick's stage musical, Flowerchildren: The Mamas and Papas Story, was produced by Magnormos in Melbourne, Australia, in 2011 and revived in 2013.[133][134]

Discography

The Mamas and the Papas' recordings were released on Dunhill Records until 1967, when the company was sold and the label became ABC-Dunhill.[135] Around 1973, ABC-Dunhill discarded all multi-track session recordings and mono masters because they were deemed obsolete and too expensive to store; Jay Lasker (1924–1989),[136] co-founder of Dunhill and by then president of ABC, is "usually the one blamed" for the decision.[137] The original recordings of The Mamas and the Papas, and of labelmates such as Three Dog Night, are therefore lost, and it has been necessary to create digital versions from the stereo album masters, often second- or third-generation tapes. This is why the sound quality of Mamas and Papas' reissues does not match the best from the 1960s. In 2012, Sundazed Records located a mono master of If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears in the UK and released it on 180-gram vinyl and a limited edition of 500 compact discs.[138]

Studio albums

| Year | Album | Catalog number (U.S.) | U.S. Billboard 200[139] | U.S. Cashbox | UK[140] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears | Dunhill D 50006 (Mono)/DS 50006 (Stereo) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1966 | The Mamas and the Papas | Dunhill D 50010/DS 50010 | 4 | 5 | 24 |

| 1967 | The Mamas and the Papas Deliver | Dunhill D 50014/DS 50014 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 1968 | The Papas and the Mamas | Dunhill DS 50031 | 15 | 10 | – |

| 1971 | People Like Us | Dunhill DSX 50106 | 84 | 45 | – |

Live album

| Year | Album | Catalog number (U.S.) | U.S. Billboard 200[139] | U.S. Cashbox | UK[140] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International Pop Festival | Dunhill DSX 50100 | – | – | – |

Singles

| Year | Title | Catalog number (U.S. unless otherwise indicated) | Chart positions | Album (both sides unless otherwise indicated) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billboard Hot 100[139] | Cashbox | UK[140] | AU | ||||

| 1965 | "Go Where You Wanna Go" B-side: "Somebody Groovy" |

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears | |||||

| 1965 | "California Dreamin'" B-side: "Somebody Groovy" |

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears | |||||

| 1966 | "Monday, Monday" B-side: "Got a Feeling" |

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears | |||||

| 1966 | "I Saw Her Again" B-side: "Even If I Could" |

The Mamas and the Papas | |||||

| 1966 | "Words of Love" Double A-side with "Dancing in the Street" (US-only) |

The Mamas and the Papas | |||||

| 1966 | "Dancing in the Street" Double A-side with "Words of Love" (US-only) |

The Mamas and the Papas | |||||

| 1966 | "Words of Love" B-side: "I Can't Wait" (UK-only) |

The Mamas and the Papas | |||||

| 1966 | "Look Through My Window" B-side: "Once Was A Time I Thought" (from The Mamas and the Papas) |

Deliver | |||||

| 1967 | "Dedicated to the One I Love" B-side: "Free Advice" |

Deliver | |||||

| 1967 | "Creeque Alley" B-side: "Did You Ever Want To Cry" |

Deliver | |||||

| 1967 | "Glad to Be Unhappy" B-side: "Hey Girl" (Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 Chart No. 134) (from If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears) |

Golden Era Vol. 2 | |||||

| 1967 | "Dancing Bear" B-side: "John's Music Box" (from Deliver) |

The Mamas and the Papas | |||||

| 1967 | "Twelve Thirty" B-side: "Straight Shooter" (Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 Chart No. 130) |

The Papas and the Mamas | |||||

| 1968 | "Safe in My Garden" B-side: "Too Late" |

The Papas and the Mamas | |||||

| 1968 | "Dream a Little Dream of Me" B-side: "Midnight Voyage" Peaked at No. 2 US Adult Contemporary |

The Papas and the Mamas | |||||

| 1968 | "For the Love of Ivy" B-side: "Strange Young Girls" (from The Mamas and the Papas) |

The Papas and the Mamas | |||||

| 1968 | "Do You Wanna Dance" B-side: "My Girl" (from Deliver) |

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears | |||||

| 1972 | "Step Out" B-side: "Shooting Star" Peaked at No. 25 US Adult Contemporary |

People Like Us | |||||

Charting compilations

| Year | Album | Catalog number (U.S.) | U.S. Billboard 200[139] | U.S. Cashbox | UK[140] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | The Best of the Mamas and the Papas: Farewell to the First Golden Era | Dunhill D 50025/DS 50025 | 5 | 5 | – |

| 1968 | Golden Era Vol. 2 | Dunhill DS 50038 | 53 | 41 | – |

| 1969 | Hits of Gold | Stateside 5007 | – | – | 7 |

| 1969 | 16 of Their Greatest Hits | Dunhill DS 50064 | 61 | 72 | – |

| 1973 | 20 Golden Hits | Dunhill DSX 50145 | 186 | 161 | – |

| 1977 | The Best of the Mamas and the Papas | Arcade ADEP 30 | – | – | 7 |

| 1995 | California Dreamin': The Very Best of the Mamas and the Papas | Polygram 5239732 | – | – | 14 |

| 1997 | California Dreamin': The Greatest Hits of the Mamas and the Papas | Telstar TTVCD 2931 | – | – | 30 |

| 2006 | California Dreamin': The Best of the Mamas and the Papas | Universal TV 9841715 | – | – | 21 |

Footnotes

- ^ "The Mamas and the Papas", Last.fm. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 36 - The Rubberization of Soul: The great pop music renaissance. [Part 2]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ John Phillips with Jim Jerome, Papa John: An Autobiography (New York: Dolphin Books / Doubleday, 1986), p. 130.

- ^ Denny Doherty, Dream a Little Dream of Me (the Nearly True Story of the Mamas and the Papas), Denny Doherty Website. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin': The True Story of the Mamas and the Papas (New York: Warner Books, 1986), pp. 72-73.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 139.

- ^ Quoted in Matthew Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go: The Oral History of The Mamas and the Papas (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002), p. 47. Doherty, John Phillips, and Michelle Phillips had discovered the islands on a ten-day holiday a little earlier, probably January 1965.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 120-122.

- ^ Including Denny Doherty and guitarist Eric Hord. Both quoted in Greenwald, Go Where You Want to Go, pp. 37, 45.

- ^ Quoted in Greewald, Go Where You Wanna Go, p. 27.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 127.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , p. 52-54.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 129.

- ^ See also Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, p. 154.

- ^ Barry McGuire, quoted in Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, pp. 15-16.

- ^ Eddi Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me: The Life of Mama Cass Elliot (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 2005), p. 165.

- ^ "Biography: Eve of Destruction", Barry McGuire Website. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, pp. 168-169.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 138.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, p. 169.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 138, 142.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, pp. 164, 168.

- ^ "Biography: California Dreamin'", Barry McGuire Website. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "I Wanna Be a Star: The 45s", David Redd's Mamas and Papas Pages. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ John Phillips says "Go Where You Wanna Go" was released only in Hawaii, where it failed, and was quickly followed by "California Dreamin'"; he implies that the first single was pulled, but does not say so explicitly. See John Phillips, Papa John, p. 141.

- ^ Lou Adler recalls, "It's a gray area for me now, but we out put out [sic] "Go Where You Wanna Go," and I had it out maybe a week or so when we shipped it when we finished "California Dreamin'." I just though[t] that it was a better first record. And we just stopped the presses on that, and released "California Dreamin'." It was not really "test marketed" in Hawaii, which is what some people think, although we may have gotten our first responses from there. We didn't send it out to test it in order to put it out." Quoted in Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, p. 98.

- ^ "Does anyone here own the "Go Where You Wanna Go" 45 (Dunhill 4018)?" Steve Hoffman Music Forums, 26–27 July 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , pp. 84-87.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 140-141; 147-148.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , pp. 80-81.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 136.

- ^ Doherty said, "I wrote the tune. John wrote the lyric." See Dream a Little Dream (the Nearly True Story of the Mamas and the Papas), Denny Doherty Website. Retrieved 2 May 2013. Phillips said he wrote everything, but gave Doherty a co-composer credit because he had inspired the song. See John Phillips, Papa John, p. 132.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 147-148.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , p. 87; there is an image of the letter between p. 84 and p. 85.

- ^ Gibson Artworks Website. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Doug Hall, The Mamas and the Papas: California Dreamin' (Kingston, Ontario: Quarry Press, 2000), p. 104.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , pp. 91-100.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 203.

- ^ "Jill Gibson's Vocals on the 2nd Mamas and Papas LP", Steve Hoffman Music Forums. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , p. 100.

- ^ a b Quoted in Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, p. 142.

- ^ "Email from Jill Regarding the 2nd LP", Cass Elliot Website. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Quoted in Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, p. 139.

- ^ Bones Howe Interview, Wrecking Crew Website. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Spencer Leigh, "Denny Doherty: Genre-crossing Singer with the Mamas and the Papas", The Independent, 22 January 2007.

- ^ "Dream a Little Dream", Denny Doherty Website. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, p. 229. Fiegel says Doherty arrived with forty-five minutes to spare.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 182. Phillips says Doherty arrived with ten minutes to spare.

- ^ Rock Family Trees, Season Two, Episode One: California Dreamin' , first broadcast on BBC 2, September–October 1998. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ The quote is from Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , pp. 145-146. Compare John Phillips, Papa John, p. 186: "It turned out to be one of the last shows we did, but it was a great way to go out."

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, pp. 172, 192, 215.

- ^ Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, pp. 217-220.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, pp. 237-238, 327-328.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 164, 189.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 141.

- ^ Quoted in "The Legacy of the Mamas and the Papas", Third Estate. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, p. 238.

- ^ "The Ed Sullivan Show, 24 September 1967", TV.com.

- ^ Phillips is quoted in Hall, The Mamas and the Papas, p. 128.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , p. 156.

- ^ "Pop Singer Cleared of Theft", The Times, 7 October 1967.

- ^ Harris Pickens Dawson III, b. 4 January 1943, d. 16 August 1986 in Long Beach, Brunswick County, North Carolina; see North Carolina, Deaths, 1931-1994, at Family Search. Retrieved 6 May 2013. Dawson is routinely described by contemporaries as a drug dealer; he was also briefly and wrongly suspected of involvement in the Manson murders. Fiegel says he was born in 1942 and that his middle name was Pickins, both of which appear to be incorrect; see Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, p. 143.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, pp. 241-243.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, pp. 244-245.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, p. 246.

- ^ a b John Phillips, Papa John, p. 196.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , p. 157. Phillips may be confusing Pic Dawson with Leland Kiefer, who accompanined Elliot on the October trip (Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, p. 239), although Elliot did continue to see Dawson while she was involved with Kiefer.

- ^ Quoted in Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, p. 247.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 207.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 207-208.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 216.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 241.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me, p. 326. The purchasing power conversion from 1970 to 2010 is based on the Consumer Price Index as calculated by Measuring Worth. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 251.

- ^ James Hunter, “John Phillips (John the Wolfking of L.A.)”, Rolling Stone, 2 November 2006. Matthew Greenwald of Allmusic also gave the album four stars. See John Phillips, John Phillips (John, The Wolf King of L.A.), Allmusic. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Quoted in the television special Straight Shooter: The True Story of John Phillips and the Mamas and the Papas.

- ^ Brewster McLeod, IMDB. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Myra Breckenridge, IMDB. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ The Man Who Fell to Earth, IMDB. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Geneviève Waïte: Romance Is on the Rise, Discogs. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Phillips 1986, pp. 19–20, 388–397.

- ^ Tim Page, "The '60s Melody Man: John Phillips Made the Mamas and the Papas Sing", Washington Post, 20 March 2001.

- ^ Neil Strauss, "John Phillips, 65, a Papa of the 1960s Group, Dies", New York Times, 19 March 2001.

- ^ Phillips, John with Jim Jerome (1986). Papa John: The Autobiography of John Phillips. New York: Doubleday.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ The documentary was released as The Mamas and the Papas: Straight Shooter on VHS videocassette by Rhino Home Video in 1989 and on DVD by Standing Room Only in 2008. Amazon. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Richard Cromelin, "Obituaries: John Phillips – Singer-Songwriter Led the Mamas and the Papas", Los Angeles Times, 19 March 2001.

- ^ Randy Lewis, "New, Solo Album from the Late John Phillips Gets Released, at Last", Los Angeles Times, 4 May 2001.

- ^ Phillips 1986, pp. 302–310.

- ^ Lee Zimmerman, "John Phillips: Phillips 66 and Denny Doherty: Waiting for a Song", Goldmine, 16 November 2001.

- ^ Joshua Klein, "John Phillips: Jack of Diamonds ", Pitchfork, 31 October 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2012. Phillips forgetfully refers to the (Jazz) Crusaders as the "Jazz Messengers"; see John Phillips, Papa John, p. 274.

- ^ Michael Parrish, "John Phillips: Pussycat", Dirty Linen, March 2009.

- ^ Craig Harris, "Andy Warhol Presents Man on the Moon: The John Phillips Space Musical", Dirty Linen, March 2010.

- ^ Mackenzie Phillips with Hilary Liftin, High on Arrival: A Memoir (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009), pp. 108, 169, 186-191.

- ^ Sean Michaels, "Daughter of the Mamas and the Papas' John Phillips reveals incestuous affair", The Guardian, 24 September 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b Nicholas Jennings, “Blasts from the Past”, Maclean’s, 11 March 1996.

- ^ Brian Bergman, “Papa Denny and His Rock ‘n’ Roll Adventure”, Maclean’s, 17 November 1997.

- ^ William McDonald, "A Rock Music Papa Finds Calmer Waters As a Children's Host", New York Times, 30 January 2000.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 185.

- ^ Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream, pp. 103, 326.

- ^ "Papa, Tell Us Another One", Maclean's, 9 July 2001

- ^ Ben Sisario, "Denny Doherty, Mamas and Papas Singer, Is Dead at 66", New York Times, 20 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Denny Doherty Discography", Mama Cass Elliot Pages. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Mamas and Papas Member Denny Doherty", Washington Post, 20 January 2007.

- ^ Here I Am: Denny Doherty and the Mamas and the Papas, Denny Doherty Website. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Here I Am: Denny Doherty and the Mamas and the Papas. IMDB. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, IMDB. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin': The True Story of the Mamas and the Papas (New York: Warner Books, 1986).

- ^ Julia Cameron, "Papa John by John Phillips with Jim Jerome and California Dreamin' by Michelle Phillips," Los Angeles Times, 21 September 1986.

- ^ "California Dreamin': The Songs of the Mamas and the Papas", IMDB. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 388.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 389.

- ^ Stephen Holden, "The Mamas and the Papas", New York Times, 15 March 1982.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, pp. 403-414, 422.

- ^ Mackenzie Phillips, High on Arrival, p. 155.

- ^ Mackenzie Phillips, High on Arrival, p. 193.

- ^ Laurie Beebe Lewis Website. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go, p. x.

- ^ John Phillips, Papa John, p. 413.

- ^ Doug Hall says the New Mamas and the Papas recorded an album and released it to critical acclaim. It occurs around 1982-1983 in the narrative, but his informant (someone called Frank Arraznati) says that it was recorded with Scott McKenzie rather than Denny Doherty, which suggests a later date. The album is not named and cannot be identified. Hall counts Half Stoned as a New Mamas and Papas album in his discography, but this is an alternative title for John Phillips' sessions with the Rolling Stones. See Hall, The Mamas and the Papas, pp. 187-189.

- ^ The Mamas and the Papas: Dreamin' Live, Allmusic. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ The Mamas and the Papas: Complete Anthology, Allmusic. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Jaime Gill, "Mamas and the Papas Anthology Review", BBC Music, 10 October 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Doug Hall, The Mamas and the Papas: California Dreamin' (Kingston, Ontario: Quarry Music Books, 2000).

- ^ Matthew Greenwald, Go Where You Wanna Go: The Oral History of the Mamas and the Papas (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002).

- ^ Jon Johnson, Make Your Own Kind of Music: A Career Retrospective of Cass Elliot (Hollywood, CA: Music Archives Press, 1987).

- ^ Eddi Fiegel, Dream a Little Dream of Me: The Life of Mama Cass Elliot (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 2005).

- ^ Rachel Deahl, "Deals", Publishers Weekly, 13 December 2010.

- ^ Chris Campion, "King of the Wild Frontier", The Observer, 15 March 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ Chris Campion, "John Phillips: A Lifetime of Debauched and Reckless Behaviour", The Daily Telegraph, 25 September 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Michael Fleming, "Fox Rocks Mamas and Papas Pix", Daily Variety, 22 August 2000.

- ^ Sheila Weller, "California Dreamgirl", Vanity Fair, December 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Flowerchildren Website. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Reuben Liversidge, "Flowerchildren: The Mamas and the Papas Story," Arts Hub, 27 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2103.

- ^ "Bobby [Roberts] and Lou [Adler], some time earlier, had come to us and begged us to give them a two-year extension on our contract...based on that we agreed to the extension, and we woke up two days later to read in the trades that Dunhill had been sold. Maybe for business reasons, whatever, we could not be told. At any rate we were sold, and it was a real nasty piece of business. Bobby, Lou, and Jay [Lasker] picked up a million apiece – we got nothing. We would one day look back and see that it was the beginning of the end for our recording, really. ABC did not understand us at all". Michelle Phillips, California Dreamin' , pp. 128-129.

- ^ Jay Harold Lasker né Lagusker, b. 7 January 1924, New York, NY, d. 11 June 1989, Los Angeles, CA; see California, Death Index, 1940-1997, at Family Search. Retrieved 5 May 2013. The son of Russian immigrants, Lasker worked in the record industry for more than forty years, including stints at Decca, Vee-Jay, Reprise, Dunhill, ABC-Dunhill, Ariola, and finally Mowtown; see "Jay Lasker, Recording Executive, 65, Dies", New York Times, 13 June 1989. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ "Mamas and Papas mono Eyes and Ears master tape found in UK", Cass Elliot Website. Retrieved on 6 May 2013.

- ^ "The Mamas and the Papas: If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears",. Sundazed.com. Retrieved on 15 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d The Mamas and the Papas Chart Positions, Allmusic. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Official Charts Company Archive. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

External links

- Cass Elliot Website.

- Dream a Little Dream: The History of the Mamas and the Papas as Remembered by Denny Doherty.

- The John E A Phillips Appreciation Group on Facebook.

- Transcription of an Interview with Scott McKenzie and John Phillips.

- The Mamas & the Papas interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- The Mamas and the Papas Vocal Group Hall of Fame Page.

- Analysis of the lyrics of "Creeque Alley".