The Nightingale (fairy tale)

| "The Nightingale" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Hans Christian Andersen | |

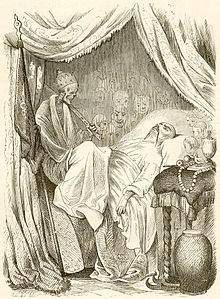

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen | |

| Original title | Nattergalen |

| Country | Denmark |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication | |

| Publisher | C.A. Reitzel |

| Publication date | 1843 |

"The Nightingale" (Danish: "Nattergalen") is a literary fairy tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen about an emperor who prefers the tinkling of a bejeweled mechanical bird to the song of a real nightingale. When the Emperor is near death, the nightingale's song restores his health. Well received upon its publication in Copenhagen in 1843 in New Fairy Tales, the tale is believed to have been inspired by the author's unrequited love for opera singer Jenny Lind, the "Swedish nightingale". The story has been adapted to opera, ballet, musical play, television drama and animated film.

Plot

The Emperor of China learns that one of the most beautiful things in his empire is the song of the nightingale. When he orders the nightingale brought to him, a kitchen maid (the only one at court who knows of its whereabouts) leads the court to a nearby forest, where the nightingale agrees to appear at court, where it remains as the Emperor's favorite. When the Emperor is given a bejeweled mechanical bird he loses interest in the real nightingale, who returns to the forest. The mechanical bird eventually breaks down; and the Emperor is taken deathly ill a few years later. The real nightingale learns of the Emperor's condition and returns to the palace; whereupon Death is so moved by the nightingale's song that he allows the Emperor to live.

Composition and publication

According to Andersen's date book for 1843, "The Nightingale" was composed on 11 and 12 October 1843,[1] and "began in Tivoli", an amusement park and pleasure garden with Chinese motifs in Copenhagen that opened in the summer of 1843.[2]

The tale was first published by C.A. Reitzel in Copenhagen on 11 November 1843 in the first volume of the first collection of New Fairy Tales. The volume included "The Angel", "The Sweethearts; or, The Top and the Ball", and "The Ugly Duckling". The tale was critically well received, and furthered Andersen's success and popularity.[3] It was reprinted on 18 December 1849 in Fairy Tales and again, on 15 December 1862 in the first volume of Fairy Tales and Stories.[4]

Jenny Lind

Andersen met Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind (1820–1887) in 1840, and experienced an unrequited love for the singer. Lind preferred a platonic relationship with Andersen, and wrote to him in 1844, "God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister". Jenny was the illegitimate daughter of a schoolmistress, and established herself at the age of eighteen as a world class singer with her powerful soprano. Andersen's "The Nightingale" is generally considered a tribute to her.[5][6][7]

Andersen wrote in The True Story of My Life, published in 1847, "Through Jenny Lind I first became sensible of the holiness of Art. Through her I learned that one must forget one's self in the service of the Supreme. No books, no men, have had a more ennobling influence upon me as a poet than Jenny Lind".

"The Nightingale" made Jenny Lind known as The Swedish Nightingale well before she became an international superstar and wealthy philanthropist in Europe and the United States. Strangely enough, the nightingale story became a reality for Jenny Lind in 1848–1849, when she fell in love with the Polish composer Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849). His letters reveal that he felt "better" when she sang for him, and Jenny Lind arranged a concert in London to raise funds for a tuberculosis hospital. With the knowledge of Queen Victoria, Jenny Lind attempted unsuccessfully to marry Chopin in Paris in May 1849. Soon after, she had to flee the cholera epidemic, but returned to Paris shortly before he died of tuberculosis on 17 October 1849. Jenny Lind devoted the rest of her life to enshrining Chopin's legacy. Lind never recovered. She wrote to Andersen on 23 November 1871 from Florence: "I would have been happy to die for this my first and last, deepest, purest love."[8]

Andersen, whose own father died of tuberculosis, may have been inspired by "Ode to a Nightingale" (1819), a poem John Keats wrote in anguish over his brother Tom's death of tuberculosis. Keats even evokes an emperor: "Thou was not born for death, immortal Bird! / No hungry generations tread thee down / The Voice I hear this passing night was heard / In ancient days by emperor and clown". Keats died of tuberculosis in 1821, and is buried in Rome, a city that continued to fascinate Andersen long after his first visit in 1833.[8]

Lars Bo Jensen has criticized the Hans Christian Andersen/Jenny Lind theory: "...to judge Andersen from a biographical point of view only is to reduce great and challenging literature to casebook notes. Thus it is a pity to regard "The Nightingale" as simply the story of Andersen's passion for the singer Jenny Lind, when it is equally important to focus on what the tale says about art, love, nature, being, life, and death, or on the uniquely beautiful and highly original way in which these issues are treated. Andersen's works are great, but it has become customary to make them seem small. It has been and still is the task of interpreters of Hans Christian Andersen's life and work to adjust this picture and to try to show him as a thinking poet."[9]

Jeffrey and Diane Crone Frank have noted that the fairy tale "was no doubt inspired by Andersen's crush on Jenny Lind, who was about to become famous throughout Europe and the United States as the Swedish Nightingale. He had seen her that fall, when she was performing in Copenhagen. Copenhagen's celebrated Tivoli Gardens opened that season, and its Asian fantasy motif was even more pronounced than it is today. Andersen had been a guest at the opening in August and returned for a second visit in October. In his diary that night he wrote: 'At Tivoli Gardens. Started the Chinese fairy tale.' He finished it in two days."[10]

Heidi Anne Heiner of SurLaLune Fairy Tales has observed, "The tale's theme of 'real' vs. 'mechanical/artificial' has become even more pertinent since 1844 as the Industrial Revolution has led to more and more artificial intelligences, machines, and other technologies. The tale gains more poignance in the age of recorded music."[3]

Adaptations and allusions

The story has inspired the creation of several notable adaptations. One of the best known is Russian composer Igor Stravinsky's opera Le Rossignol (1914, rev. 1962), a 35-minute, 3-act opera with a libretto by the composer and Stepan Mitusov. Le chant du rossignol, a 20-minute symphonic poem was constructed by Stravinsky from the opera's score in 1917 and accompanied a ballet presented in 1920 by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes with sets by Henri Matisse and choreography by Léonide Massine.[3] The tale has seen two noteworthy animated film productions: Lotte Reiniger's shadow puppet production "The Chinese Nightingale" in 1927, and Czech Jiří Trnka's "The Emperor's Nightingale" in 1948.[3]

Nightingale: A New Musical, premiered in London on 18 December 1982 starring Sarah Brightman. On television, the tale was adapted for Shelley Duvall's Faerie Tale Theatre in 1983 with Mick Jagger as the Emperor, Bud Cort as the Music Master, Barbara Hershey as the Kitchen Maid, Edward James Olmos as the Prime Minister, and Shelley Duvall as the Nightingale and Narrator.[3]

A mechanical nightingale is featured in King's Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow and is used to replace a real nightingale for a princess.

The title is featured in The House on Mango Street, comparing Ruthie to him.[citation needed]

Jerry Pinkney adapted the story in a 2002 children's picture book.

In 2007, the National Bank of Denmark issued a 10 DKK commemorative coin of "The Nightingale".[11]

In 2008 Flemish author Peter Verhelst and illustrator Carll Cneut published their adaptation of the story in the children's book Het geheim van de keel van de nachtegaal.

The story is briefly alluded to in the anime The Big O. In the episode, Dorothy, Dorothy, the character of R. Dorothy Wainwright is revealed be an android, built for a wealthy businessman, Timothy Wainwright, to replace his daughter who had died years ago. Her builder even refers to her as "nightingale."[citation needed]

In 2013, Marianne Burton's first collection of poems, She Inserts The Key, was published by Seren. The title also constitutes the first four words of one of the poems within the collection, entitled 'The Emperor and The Nightingale.' The story the poem tells advances beyond the bounds of the original fairy tale to powerful effect but is clearly connected to it. The fascination with the mechanical is most evident.[citation needed]

In the 2010 Best Foreign Film Academy Award winner, In A Better World, the protagonist Christian when first on screen is seen from behind, reading an excerpt from The Nightingale at his mother's funeral. (Film: In a Better World, directed by Susanne Bier)

Gallery

-

How common it looks, said the chamberlain[12]

-

The ladies took some water into their mouths to try and make the same gurgling, thinking so to equal the nightingale.[12]

-

The music-master wrote five-and-twenty volumes about the artificial bird.[12]

-

Even Death himself listened to the song and said, 'Go on, little nightingale, go on!'[12]

Notes

- ^ Andersen 1980, p. 253

- ^ Nunnally 2005, p. 429

- ^ a b c d e Heiner

- ^ The Nightingale: Editions

- ^ Liukkonen

- ^ Hetsch, Gustav (July 1930). "Hans Christian Andersen's Interest in Music". The Musical Quarterly. 16 (3). Oxford University Press: 322–329. doi:10.1093/mq/xvi.3.322. JSTOR 738371.

- ^ Rosen, Carole (2004). "Lind, Jenny (1820–1887)". In Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, Brian (eds.). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198614111. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b Jorgensen

- ^ Jensen

- ^ Andersen 2003, p. 139

- ^ "The Nightingale". National Bank of Denmark. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Andersen, Hans Christian. "The Nightingale". Stories from Hans Christian Andersen. London: Stodder & Houghton. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

References

- Andersen, Hans Christian; Conroy, Patricia L. (transl.); Rossel, Sven H. (trans.) (1980). Tales and Stories by Hans Christian Andersen. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Andersen, Hans Christian; Frank, Jeffrey; Frank, Diana Crone (2003). The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen: A New Translation from the Danish. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Heiner, Heidi Anne (7 July 2007). "History of "The Nightingale"". SurLaLune. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- Jensen, Lars Bo. "Criticism of Hans Christian Andersen". Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- Johansen, Bertil Palmar; Haugan, Asbjørg (1987). "Keiseren og nattergalen". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- Jorgensen, Cecilia (17 March 2005). "Did the Emperor Suffer from Tuberculosis?". Icons of Europe. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- Petri Liukkonen. "Hans Christian Andersen". Books and Writers.

- Nunnally, Tiina (2005). Fairy Tales. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-03377-4.

- "The Nightingale: Editions". Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- Tatar, Maria (2008). The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06081-2.

- Burton, Marianne (2013) She Inserts the Key. Seren is the book imprint of Poetry Wales Press Ltd, Bridgend. www.serenbooks.com

External links

- "Nattergalen": Original Danish text

- "The Nightingale": English translation by Jean Hersholt

- "Did the emperor suffer from tuberculosis?", essay of 17 March 2005 researched and written by Cecilia Jorgensen for World Tuberculosis Day.

The Nightingale public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Nightingale public domain audiobook at LibriVox

![How common it looks, said the chamberlain[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_2.jpg/96px-Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_2.jpg)

![The ladies took some water into their mouths to try and make the same gurgling, thinking so to equal the nightingale.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/34/Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_3.jpg/96px-Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_3.jpg)

![The music-master wrote five-and-twenty volumes about the artificial bird.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_4.jpg/95px-Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_4.jpg)

![Even Death himself listened to the song and said, 'Go on, little nightingale, go on!'[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_5.jpg/96px-Edmund_Dulac_-_The_Nightingale_5.jpg)