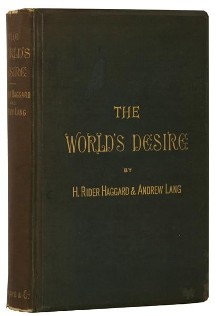

The World's Desire

First edition | |

| Author | H. Rider Haggard and Andrew Lang |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy novel |

| Publisher | Longmans |

Publication date | 1890 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 316 pp |

The World's Desire is a classic fantasy novel first published in 1890 and written by H. Rider Haggard and Andrew Lang.[1][2] Its importance was recognised in its later revival in paperback by Ballantine Books as the fortieth volume of the celebrated Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in January 1972.

The World's Desire is the story of the hero Odysseus, mainly referred to as "the Wanderer" for the bulk of the novel. Odysseus returns home to Ithaca after his second, unsung journey. He is hoping to find a "home at peace, wife dear and true and his son worthy of him".[3] Unfortunately, he does not find any of the three, instead his home is ravaged by a plague and his wife Penelope has been slain. As he grieves, he is visited by an old flame, Helen of Troy, for whom the novel is named. Helen leads him to equip himself with the Bow of Eurytus and embark on his last journey. This is an exhausting journey in which he encounters a Pharaoh who is wed to a murderess beauty, a holy and helpful priest, and his own fate.

Book I

Odysseus, sometimes addressed as Ulysses or simply “the Wanderer,” is returning home from his unsung, second wandering. The son of Laertes was required to wander until he reached the land of men who have never tasted salt. Odysseus had endured the curse, fulfilled the prophecy and wanted only to return to a “home at peace, wife dear and true and his son worthy of him”[4] This was not the home he found. He returns to his home to find upon the arm of a stranger the gold bracelet he had given his wife, Penelope. Overwhelmed with his grief, Odysseus takes solace when he find the Bow of Eurytus and his armour, still intact. With these in his possession, he continues on through Ithaca. Along the way, Odysseus stops to rest at the Temple of Aphrodite and is accosted by the vision of the young and beautiful Helen of Troy, a previous love. The vision tells him to find Helen, leaving him with a renewed sense of purpose and a full chalice of wine. He sleeps, and wakes during his capture by the Sidonians. He travels with them for a time, while he plots, then launches his escape. When he escapes and casts the Sidonian bodies overboard, he happens upon a pilot and continues on his journey to Tanis and the Sanctuary of Heracles (the Safety of Strangers). It was not long before word had spread of his ways. He was accepted to see Pharaoh Meneptah and his beautiful and listless queen Meriamun, who faints at seeing Odysseus although he does not know why. Queen Meriamun and the Pharaoh are half brother and sister. Their marriage is not a happy union but is rather fuelled with competitive feelings of animosity. A story is told to Odysseus by the Priest Rei describing one such competitive bought between Meriamun and the Pharaoh that ended with a stabbing attempt on the Pharaoh from Meriamun and her promise to leave and search until she finds a man worthy of her love. Eventually, Meriamun swallowed her pride and agreed to her father and the prince's wish that she wed. However, this was not without a price. She demanded that she be equal in all things to the Pharaoh, it was granted and from that point on she was pacified toward the Prince. Though before her wedding night, Meriamun was outraged that she must act as the Pharaoh's wife, she returns to Rei the next night, pacified and speaking of dreams. In one dream in particular, Meriamun encounters a man, who is not the Pharaoh, but who she loves very much. In the dream she was competing for the love of this man with another, more beautiful, woman. After the dream was revealed to Rei, they spoke of it no more. Rei moves on in his story. Osiris died and Meneptah and Meriamun reigned. She provided one child and ruled with authority. Meneptah lost interest in vying for the Queen's love and so began an open affection for one of her beautiful ladies, Hataska. Hataska was her first lady and tried to openly declare herself the Queen's equal in the Pharaoh's affection and power. The Queen quickly disposed of the threat to her power in an act that angered the Pharaoh but also instilled a fear of her that overcame wrath. Concerned about the consequences of her actions, Meriamun visits Osiris's tomb and channels Hataska. The Khou informs her that “Love shall be the burden of thy days, and Death shall be the burden of thy love”.[5] Rei closes book one by informing Odysseus that the Queen was troubled with his appearance because he is the man she has been warned about and will not be able to control herself in regards to him.

Book II

Odysseus assures Rei that he does not seek the love of Meriamun, but rather another maiden. The Pharaoh and Meriamun invite Odysseus to feast and as things are becoming merry, two men show up, frightening even the guards. All of the guests hide their faces from these men, except for Meriamun and Odysseus. The men ask the Pharaoh to let their people go, the Pharaoh, softened and on the verge of doing so, hesitates when Meriamun interferes. They send the men on their way and speak of the difficulties the land has experienced as a result of the sudden appearance and then vanishing of a strange and beautiful witch. The feast continues on, until a mummy enters and approaches the Pharaoh. The mummy speaks of death and conversation between the Pharaoh and Odysseus becomes uncomfortable. The King challenges Odysseus to drink and Odysseus becomes angry and drains the cup. Odysseus's bow begins to sing, giving itself away as the Bow of Odysseus and warning the party that foes are near. With that a woman enters, carrying the body of the Pharaoh and Meriamun's only and first-born son. Meriamun blames the death on the False Hathor. The guests, however, disagree, saying it is not her, but rather the Gods of the Dark Apura, who the Queen will not let go. The people turn on Meriamun. Violence ensues and as it is settling down a voice rises up demanding of the Pharaoh “Now wilt thou let the people go?” The Pharaoh expels the living from the building. It is later when Odysseus is bronzing his armour that Rei comes to speak with him. Rei explains about the deaths surrounding the Holy Hathor. One by one, men go to embrace her and are struck immediately down. The Apura re-emerge and it is decided that Odysseus shall be the commander of this war. Soon after, Meriamun calls Odysseus into her chamber and requests that he look her in the eye and deny his identity. She then shows him a disturbing vision and he comes forth with the truth: he had been sent in search of a woman to this place. Meriamun wants to make sure that she is that woman. Unable to hurt Meriamun with the truth, Odysseus resists her advances by claiming it is his oath to the Pharaoh that keeps him from her. Next, Odysseus informs Rei that he is going to see the Temple of Hathor. The Beauty appears to Odysseus and sings and no man is immune to her charm. Odysseus stands with his head facing downward and tries to evaluate what he has just seen. She is the Golden Helen. He risks a closer look and makes it into the innermost recesses of the shrine, seeing that the guards were all long deceased heroes. He finally tears through to the center of the tomb and the World’s Desire was there. She looks at Odysseus in terror, thinking he is her former husband, Paris. Paris had used shape shifting to trick Helen before and so now she saw Odysseus as Paris posing as Odysseus. Odysseus reveals himself to be the true Odysseus of Ithaca and, and after showing her his scar, Helen believes him. They agree to meet again, he mentions nothing of Meriamun. Meriamun is upset when she hears Odysseus went to see the Hathor and lived to return. She calls Odysseus to dine with her and then see her in chamber. He goes and upon returning to his own chamber he is greeted with the vision of Helen. He is sceptical, but she wins him over and has him make an oath that he would not leave her. He kisses who he thought was Helen, but goes to bed with Meriamun. When he awakes, he is terrified to find himself with the Pharaoh’s queen.

Book III

The Queen and Odysseus stand in her chamber. Meriamun is calm and victorious, Odysseus betrayed and full of rage. The Queen points out his oath, she will constantly be at his side forever. Kurri, the Sidonian, reappears and becomes the Queen’s accomplice. Helen comes to speak with the Queen and the Queen urges Kurri to stab her. He is unable to, and Helen speaks. She wants to know how Meriamun was able to bring Odysseus such shame. Helen speaks gently, and momentarily the Queen finds herself pacified. However, she then comes to her senses and realises she cannot let Helen go. However, no guards or doors are immune to Helen’s beauty, except one, who was eventually killed by an arrow aimed at Helen. Helen told the Queen that no man could do her harm, but the Queen continues her attempts. Helen succeeds and passes through the gates. At her escape, the Queen dooms those who let her pass to die. Rei stops to pray for their lives and the Queen is outraged. The Pharaoh returns to see the number of men killed. He wonders when Death has had enough. The Queen blames the deaths on the Hathor passing through. The Pharaoh informs the Queen that he the Apura name Jahveh has passed and has killed tens of thousands in his path. A messenger than appears informing the Pharaoh and Queen that a mighty host approaches the city. The Pharaoh inquires of the Queen as to the presence of Odysseus. The Queen tells a story to the Pharaoh which fills him at rage toward Odysseus. Odysseus lay on the bed of torment in the place of torment. The Queen speaks to him and he is relieved to know he will see Helen again. The Queen caused the Pharaoh to have dreams in which his father tells him to release Odysseus and set him to take over their armies. Odysseus leaves and the Pharaoh and Queen go to feast. The Pharaoh loves the Queen despite her evil and she hates him more for it. The Queen kills the Pharaoh with a poison cup of wine, as she had Hataska. The Queen claims the Pharaoh’s death to be the Hathor’s doing and rallied the women to take vengeance on the Hathor. Rei warns Helen and tells Helen the tale as to how Meriamun trapped Odysseus and had him swear by a snake, when he should have sworn to a star. Meriamun lead the women to the temple and charged. They set fire to the temple. Helen beckoned Rei and they rode through the fire. Odysseus partook in his last battle as an oath to the Pharaoh. He found himself surrounded when Helen appeared. She forgave him and told him this was to be his last battle. Meriamun comes and tells Odysseus of the Pharaoh’s death. She informs him he will be the new Pharaoh. Odysseus acknowledges that her plans did not work because he is dying. Helen and Meriamun both vow to see Odysseus again. He dies, they set his body on fire and then Meriamun joins him in the fire to die as well as Helen walks away to continue wandering until Odysseus will again join her.

Characters

- Odysseus

- Penelope

- The Sidonians

- The Pilot

- Meneptah, the Pharaoh, the Prince, the King

- Meriamu, the Queen

- Rei the Priest

- Hataska, the First Lady

- Kurri

- Helen

- Osiris

Concept and creation

In 1890, Andrew Lang was an influential man of letters; Rider Haggard was the author of sensational adventure novels. When the friends wrote a novel together, they chose a subject near to Lang's Hellenist heart.[6] The World's Desire picks up the Odyssey where Homer left off and shows a widowed Odysseus voyaging to find his heart's desire, Helen of Troy. Andrew Lang is perhaps known more for his translations of The Odyssey and The Iliad than for anything else, except maybe his input in Grimm fairytales. His translations have been called the "most influential English translations of Homer in the nineteenth century".[7] It is Lang's extensive background in the translations of Homer's work that enabled the tone and wording of the novel to so effortlessly capture the essence of the previous works on which it was based. To compose The World's Desire, first they returned to the Helen theme Lang had used in his long poem Helen of Troy, published five years earlier. From there, they decided that The World's Desire was to be about Helen and Odysseus in Egypt, where Haggard had previously set two romances- She and Cleopatra. It was Lang's noncollaborative contribution in the first four chapters, as well as his input throughout the rest of the novel, that gives the novel an allegorical level that makes it nearly as strong as any folklore in the Grimm's tales.

Collaboration

The World's Desire was not the first time Haggard and Lang worked together. During their collaboration, Lang helped Haggard plan and revise She, Allan's Wife, Beatrice, Eric Brighteyes, Nada the Lily and also added poems to Cleopatra.[8] The pair also carried on a correspondence on the dedication pages of their separate works. They were very supportive of each other's progress and proud of the advancements in the romance genre they had made. Lang wrote poems hailing Haggard and their colleague Stevenson for bringing romance novels back to life. While Lang appreciated Haggard's imagination, he was continually attempting to give shape to Haggard's florid prose style.[9] For the greater part of the novel The World's Desire, Haggard is responsible for the final form, having reworked Lang's revisions, while the first four chapters (including the Greek episode), written after the central portion, are wholly Lang's. Their collaboration was a turning point in the genre of romance. For the two men, writing about Greece- a homosexual utopia- was an act calculated to reassert the masculinity of British fiction and to steal fire back from women writers.[10] In fact, one goal of Lang's partnership with Haggard was the exclusion of women based on his belief that women were incapable of understanding male romance novels.

Style

The style can be wholly attributed to Lang's extensive experience with the language and composition of Homer's works through his own translations of them. This familiarity is what allows The World's Desire to be read as a thorough extension of The Odyssey in everything from diction and tone to the clear and direct language. Another influence on the style of the piece is the accuracy that is attributed through Haggard's time in South Africa.

Adventure romance

This novel is of the "romance" genre often associated with authors such as Haggard, Lang, and Stevenson. The term "pure romance" offered male writers of the time a refuge from women's fiction, but also from an England that they imagined Queen Victoria had feminised.[11] In The World's Desire, Haggard and Lang envision Odysseus (Ullysses) dying for love of Helen of Troy, a death that culminates a lifelong search for “Beauty's self.” Odysseus illustrates an unending pursuit of adventure as a mark of his devotion to imagination, spirit, and the wilderness and also key attributes to adventure romance- stormy, savage, bestial, passionate, uncontrolled, unknown, magical, and deadly.[12] Wendy Katz says that the most significant conclusion to be drawn from the examination of romance at the time this novel was published, is that romance as a genre is immune to the ties of actuality. This means that it is a literary form characterised by freedom and expansiveness.[13] These two attributes of romance mean that romance characters can be set free from time, place and history. Especially in Haggard's writings, the restraints of time are subverted by any number of rebirths, doubles, reincarnations, or returns to former lives. While Odysseus is not fortunate enough to experience this type of freedom from time and place, in The World's Desire the ability to surpass such restrictions is illustrated in the end when Helen and Meriamun both vow that Odysseus will see each of them again.

Imperial Gothic

The age of British imperialism extends from about 1870 to 1914. Bounding one end of the period is the Franco- Prussian War, the conclusion of which, in 1873, gave French and German manufacturing interests the opportunity to launch an attack on Britain's commercial monopoly. In this way a new era of national- soon to be imperial- rivalry among nations began. The meshing of ideas and attitudes in Haggard reflects in miniature the conjunction of ideas and attitudes of the imperial age. Although it is impossible to present a perfect picture of imperialism and its mirror image in Haggard's writings, some awareness of how imperialism drew together the sundry elements of class conflict, domestic policy, party politics, and all manner of socio- economic phenomena within the sphere of foreign policy is crucial to understanding Haggard's fiction in the imperial context. One imperial idea demonstrated clearly in The World's Desire is the imperial hero. Many romance heroes of the late nineteenth century have no explicit links to Empire.[14] Odysseus is one such hero. He is a great man with a propensity for leadership, but with no ties to the Empire he defends other than an oath to do so. In addition to severing ties to Empire, aside from Helen, Odysseus separates himself from his past by deeming himself "the Wanderer" and preferring to be separated in association from his previous victories.

Reception

On 7 March 1889 the serial rights of The World's Desire were purchased by The New Review, with the first part published in April. James M. Barrie summarised the critical judgment on The World's Desire when he wrote that “collaboration in fiction, indeed, is a mistake, for the reason that two men cannot combine so as to be one.” Most reviewers, in fact, disliked the novel. The National Observer declared: “Mr. Lang we know and Mr. Haggard we know: but of whom (or what?) is this ‘tortuous and ungodly’ jumble of anarchy and culture?... This cryptic was moved to curse his literary gods and die at the thought of the most complete artistic suicide it has ever been his lot to chronicle”.[15] Haggard was too busy to mind the criticism; however, Lang was infuriated by it.

Feminist interpretations

Light and dark female rivals, Helen and Queen Meriamun, both cause men's deaths; Odysseus is "beguiled" by the snake of Meriamun, as was Eve, and the Argive Helen dwells with death, yet she is “beauty's self.” These characters represent abstractions, rather than individuals.[16] The hero is the ideal to which the reader is meant to aspire, but Haggard and Lane fuse together in their depiction of the fierce Meriamun. Meriamun is an embodiment of the independent New Woman they strongly disliked, however they cannot help their attachment to the character.

Sexual difference

In the opening poem of The World's Desire, the uncertainty between He and She becomes apparent. The poem describes the quicksilver alternation between the star and the snake, symbols of sexual difference:

- The fables of the North and South

- Shall mingle in a modern mouth.

- There lives no man but he hath seen

- The World’s Desire, the fairy queen…

- Not one but he hath chanced to wake,

- Dreamed of the Star and found the Snake.[17]

According to Koestenbaum, Lang and Haggard “mingle in a modern mouth”: they collaborate, two mouths speaking as one.[18] By calling mingling “modern,” they imply that collaboration and the propensity to confuse star and snake are contemporary urges. To take this a step further, it is not only that Odysseus cannot decide which woman he loves, wavering between Star and Snake, but it is also the Star and Snake's refusal to remain distinct. This leads the reader to an even more bewildering erotic choice: a confusion over which sex to love. The reader must decide whether to swear allegiance to the “blood red” menstrual star on Helen’s breast or to the snaky phallus represented with Meriamun.[19] In fact, the character of Meriamun is so sexually open-ended that it is difficult to say whether she is a man in a woman's body or a woman in a man's.

References

- Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers. p. 138.

- Haggard, H. Rider; Lang, Andrew (1894). The World's Desire. London: Longmans, Green, And Co. pp. 3, 8, 53.

- Higgins, D. S. (1983). Rider Haggard: A Biography. New York: Stein and Day. p. 143.

- Katz, Wendy (1987). Rider Haggard and the Fiction of Empire: a Critical Study of British Imperial Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 42, 44, 59.

- Langstaff, Eleanor (1978). Andrew Lang. Boston: Twayne. pp. 58, 113.

- Monsman, Gerald (2006). H. Rider Haggard on the Imperial Frontier: the Political and Literary Contexts of His African Romances. Greensboro, NC: ELT. p. 69.

- ^ John Sutherland (1990) [1989]. "The World's Desire". The Stanford Companion to Victorian Literature. p. 681.

- ^ "Review: THE WORLD'S DESIRE". The Cambridge Review. 12: 172. 29 January 1891.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider; Lang, Andrew (1894). The World's Desire. London: Longmans, Green, And Co. pp. 3, 8, 53.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider; Lang, Andrew (1894). The World's Desire. London: Longmans, Green, And Co. pp. 3, 8, 53.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider; Lang, Andrew (1894). The World's Desire. London: Longmans, Green, And Co. pp. 3, 8, 53.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Langstaff, Eleanor (1978). Andrew Lang. Boston: Twayne. pp. 58, 113.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Langstaff, Eleanor (1978). Andrew Lang. Boston: Twayne. pp. 58, 113.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). Double Talk: The Erotics of Male Literary Collaboration. New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Monsman, Gerald (2006). H. Rider Haggard on the Imperial Frontier: the Political and Literary Contexts of His African Romances. Greensboro, NC: ELT. p. 69.

- ^ Katz, Wendy (1987). Rider Haggard and the Fiction of Empire: a Critical Study of British Imperial Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 42, 44, 59.

- ^ Katz, Wendy (1987). Rider Haggard and the Fiction of Empire: a Critical Study of British Imperial Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 42, 44, 59.

- ^ Higgins, D. S. (1983). Rider Haggard: A Biography. New York: Stein and Day. p. 143.

- ^ Katz, Wendy (1987). Rider Haggard and the Fiction of Empire: a Critical Study of British Imperial Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. pp. 42, 44, 59.

- ^ Haggard, H. Rider; Lang, Andrew (1894). The World's Desire. London: Longmans, Green, And Co. p. 3.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). Double Talk: The Erotics of Male Literary Collaboration. New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.

- ^ Koestenbaum, Wayne (1989). Double Talk: The Erotics of Male Literary Collaboration. New York: Routledge. pp. 143–177.