Theodora (wife of Justinian I)

| Theodora | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augusta | |||||||||

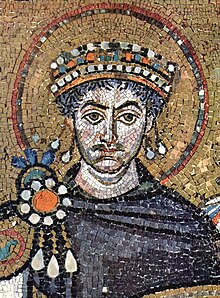

Depiction of Theodora from a contemporary portrait mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna | |||||||||

| Empress of the Byzantine Empire | |||||||||

| Reign | 9 August 527 – 28 June 548 | ||||||||

| Coronation | 9 August 527 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Ariadne (empress) | ||||||||

| Successor | Sophia (empress) | ||||||||

| Born | c. 500 Cyprus | ||||||||

| Died | 28 June 548 (aged 48) Constantinople | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | Justinian I | ||||||||

| Issue | illegitimate: John Theodora | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Justinian | ||||||||

| Religion | Miaphysite Christianity | ||||||||

| Justinian dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Chronology | ||

|

||

| Succession | ||

|

||

Theodora (/ˌθiːəˈdɔːrə/; Greek: Θεοδώρα; c. 500 – 28 June 548) was empress of the Eastern Roman Empire by marriage to Emperor Justinian I. She was one of the most influential and powerful of the Eastern Roman empresses, albeit from a humble background.[1] Some sources mention her as empress regnant with Justinian I as her co-regent. Along with her spouse, she is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, commemorated on November 14.

Historiography

The main historical sources for her life are the works of her contemporary Procopius. The historian offered three contradictory portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, largely completed in 545, paints a picture of a courageous and influential empress who saved the throne for Justinian.

Later he wrote the Secret History, which survives in only one manuscript suggesting it was not widely read during the Byzantine era. The work has sometimes been interpreted as representing a deep disillusionment with the emperor Justinian, the empress, and even his patron Belisarius. Justinian is depicted as cruel, venal, prodigal and incompetent; as for Theodora, the reader is treated to a detailed and titillating portrayal of vulgarity and insatiable lust, combined with shrewish and calculating mean-spiritedness; Procopius even claims both are demons whose heads were seen to leave their bodies and roam the palace at night. Alternatively, scholars versed in political rhetoric of the era have viewed these statements from the Secret History as formulaic expressions within the tradition of invective.

Procopius' Buildings of Justinian, written about the same time as the Secret History, is a panegyric which paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple and presents particularly flattering portrayals of them. Besides her piety, her beauty is praised within the conventional language of the text's rhetorical form. Although Theodora was dead when this work was published, Justinian was alive, and perhaps commissioned the work.[2]

Her contemporary John of Ephesus writes about Theodora in his Lives of the Eastern Saints as the daughter of a pious Monophysite priest. He mentions an illegitimate daughter not named by Procopius.[3]

Various other historians presented additional information on her life. Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora to figures not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia.

Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They contradict Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. These are late Miaphysite sources and record her depiction among members of their creed. The Miaphysites have tended to regard Theodora as one of their own and the tradition may have been invented as a way to improve her reputation and is also in conflict with what is told by the contemporary Miaphysite historian John of Ephesus.[4] These accounts are thus usually ignored in favor of Procopius.[3]

Early years

Theodora, according to Michael Grant, was of Greek Cypriot descent.[5] There are several indications of her possible birthplace. According to Michael the Syrian her birthplace was in Mabbug, Syria;[6] Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos names Theodora a native of Cyprus, while the Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia. She was born c. 500 AD.

Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer of the hippodrome's Green faction in Constantinople. Her mother, whose name is not recorded, was a dancer and an actress.[7] Her parents had two more daughters.[8] After her father's death, when Theodora was four,[9] her mother brought her children wearing garlands into the hippodrome and presented them as suppliants to the Blue faction. From then on Theodora would be their supporter.

Procopius (in his Secret History) relates that Theodora from an early age followed her sister Komito's example and worked in a Constantinople brothel serving low-status customers; later she performed on stage.[10] Theodora, in Procopius's account, made a name for herself with her salacious portrayal of Leda and the Swan.[11] Employment as an actress at the time would include both "indecent exhibitions on stage" and providing sexual services off stage; Lynda Garland in "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204" notes that there seems to be little reason to believe she worked out of a brothel "managed by a pimp". Theodora earned her living by a combination of her theatrical and sexual skills in what Garland calls the "sleazy entertainment business in the capital".[4]

During this time she met the future wife of Belisarius, Antonina, who would become a part of the women's court led by Theodora.

At the age of 16, she traveled to North Africa as the companion of a Syrian official named Hecebolus when he went to the Libyan Pentapolis as governor.[12] She stayed with him for almost four years before returning to Constantinople. Abandoned and maltreated by Hecebolus, on her way back to the capital of the Byzantine Empire, she settled for a while in Alexandria, Egypt. She is said to have met Patriarch Timothy III in Alexandria, who was Miaphysite, and it was at that time that she converted to Miaphysite Christianity. From Alexandria she went to Antioch, where she met a Blue faction's dancer, Macedonia, who was perhaps an informer of Justinian.

She returned to Constantinople in 522 and, according to John of Ephesus, gave up her former lifestyle, settling as a wool spinner in a house near the palace. The extreme and conventional nature of the negative rhetoric of Procopius and the positive rhetoric of John of Ephesus has led most scholars to conclude that the veracity of both sources might be questioned.

When Justinian sought to marry Theodora, he could not: he was heir of the throne of his uncle, Emperor Justin I, and a Roman law from Constantine's time prevented anyone of senatorial rank from marrying actresses. In 525, Justin repealed the law, and Justinian married Theodora.[12] By this point, she already had a daughter (whose name has been lost). Justinian apparently treated the daughter and the daughter's son Athanasius as fully legitimate,[13] although sources disagree whether Justinian was the girl's father.

Life as royalty

Life as Empress and Augusta

When Justinian succeeded to the throne in 527, two years after the marriage, Theodora became Empress of the Eastern Roman Empire. She shared in his plans and political strategies, participated in state councils, and Justinian called her his "partner in my deliberations."[14] She had her own court, her own official entourage, and her own imperial seal.[15]

The Nika riots

Theodora proved herself a worthy and able leader during the Nika riots. There were two rival political factions in the Empire, the Blues and the Greens, who started a riot in January 532 during a chariot race in the hippodrome. The riots stemmed from many grievances, some of which had resulted from Justinian's and Theodora's own actions.[16]

The rioters set many public buildings on fire, and proclaimed a new emperor, Hypatius, the nephew of former emperor Anastasius I. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee. At a meeting of the government council, Theodora spoke out against leaving the palace and underlined the significance of someone who died as a ruler instead of living as an exile or in hiding, reportedly saying, "royal purple is the noblest shroud".[17]

As the emperor and his counsellors were still preparing their project, Theodora interrupted them and claimed :

"My lords, the present occasion is too serious to allow me to follow the convention that a woman should not speak in a man’s council. Those whose interests are threatened by extreme danger should think only of the wisest course of action, not of conventions. In my opinion, flight is not the right course, even if it should bring us to safety. It is impossible for a person, having been born into this world, not to die; but for one who has reigned it is intolerable to be a fugitive. May I never be deprived of this purple robe, and may I never see the day when those who meet me do not call me empress. If you wish to save yourself, my lord, there is no difficulty. We are rich; over there is the sea, and yonder are the ships. Yet reflect for a moment whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you would not gladly exchange such safety for death. As for me, I agree with the adage that the royal purple is the noblest shroud."[18]

Her determined speech convinced them all, including Justinian himself, who had been preparing to run. As a result, Justinian ordered his loyal troops, led by the officers, Belisarius and Mundus, to attack the demonstrators in the hippodrome, killing (according to Procopius) over 30,000 rebels. Despite his claims that he was unwillingly named emperor by the mob, Hypatius was also put to death, apparently at Theodora's insistence.[19] Interpretations that Justinian never forgot that it was Theodora who had saved his throne depend on seeing Procopius' account as a straightforward report, and not framed to impugn Justinian with the implication that he was more cowardly than his wife.

Later life

Following the Nika revolt, Justinian and Theodora rebuilt and reformed Constantinople and made it the most splendid city the world had seen for centuries, building or rebuilding aqueducts, bridges and more than twenty five churches. The greatest of these is Hagia Sophia, considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture and one of the architectural wonders of the world.

Theodora was punctilious about court ceremony. According to Procopius, the Imperial couple made all senators, including patricians, prostrate themselves before them whenever they entered their presence, and made it clear that their relations with the civil militia were those of masters and slaves.

Not even the government officials could approach the Empress without expending much time and effort. They were treated like servants and kept waiting in a small, stuffy room for an endless time. After many days, some of them might at last be summoned, but going into her presence in great fear, they very quickly departed. They simply showed their respect by lying face down and touching the instep of each of her feet with their lips; there was no opportunity to speak or to make any request unless she told them to do so. The government officials had sunk into a slavish condition, and she was their slave-instructor.

They also carefully supervised the magistrates, much more so than previous emperors, possibly to reduce bureaucratic corruption. Theodora's jealousy of one of her ladies-in-waiting, Anastasia the Patrician, prompted the latter to flee to a monastic life in Egypt.[20][21]

Theodora also created her own centers of power like the Hagia Sophia. The eunuch Narses, who in old age developed into a brilliant general, was her protege, as was the praetorian prefect Peter Barsymes. John the Cappadocian, Justinian's chief tax collector, was identified as her enemy, because of his independent influence.

Theodora participated in Justinian's legal and spiritual reforms, and her involvement in the increase of the rights of women was substantial. She had laws passed that prohibited forced prostitution "and was known for buying girls who had been sold into prostitution, freeing them, and providing for their future."[22] She closed brothels and made pimping a criminal offense. She created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves.[12] She also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape, forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery. Procopius wrote that she was naturally inclined to assist women in misfortune.[23] After Theodora's death, "little effective legislation was passed by Justinian."[24]

Procopius' Secret History presents a different version of events. For instance, rather than preventing forced prostitution (as in Buildings 1.9.3ff), Theodora is said to have 'rounded up' 500 prostitutes, confining them to a convent. This, he narrates, even led to suicides as prostitutes sought to escape 'the unwelcome transformation.' (SH 17) As this 'history' also suggests that the royal couple were "demons whose heads were seen to leave their bodies and roam the palace at night," its veracity is heavily questioned.

Religious policy

Saint Theodora | |

|---|---|

Empress Theodora and attendants (mosaic from Basilica of San Vitale, 6th century) | |

| Empress | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Eastern Catholicism Oriental Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | November 14 |

| Attributes | Imperial Vestment |

Theodora worked against her husband's support of Chalcedonian Christianity in the ongoing struggle for the predominance of each faction.[25] As a result, she was accused of fostering heresy and thus undermined the unity of Christendom.

In spite of Justinian being Chalcedonian, Theodora founded a Miaphysite monastery in Sykae and provided shelter in the palace for Miaphysite leaders who faced opposition from the majority of Chalcedonian Christians, like Severus and Anthimus. Anthimus had been appointed Patriarch of Constantinople under her influence, and after the excommunication order he was hidden in Theodora's quarters for twelve years, until her death. When the Chalcedonian Patriarch Ephraim provoked a violent revolt in Antioch, eight Miaphysite bishops were invited to Constantinople and Theodora welcomed them and housed them in the Hormisdas Palace adjoining the Great Palace, which had been Justinian and Theodora's own dwelling before they became emperor and empress.

In Egypt, when Timothy III died, Theodora enlisted the help of Dioscoros, the Augustal Prefect, and Aristomachos the duke of Egypt, to facilitate the enthronement of a disciple of Severus, Theodosius, thereby outmaneuvering her husband, who had intended a Chalcedonian successor as patriarch. But Pope Theodosius I of Alexandria, even with the help of imperial troops, could not hold his ground in Alexandria against Justinian's Chalcedonian followers. When he was exiled by Justinian along with 300 Miaphysites to the fortress of Delcus in Thrace, Theodora rescued him and brought him to the Hormisdas Palace. He lived under her protection and, after her death in 548, under Justinian's.

When Pope Silverius refused Theodora's demand that he remove the anathema of Pope Agapetus I from Patriarch Anthimus, she sent Belisarius instructions to find a pretext to remove Silverius. When this was accomplished, Pope Vigilius was appointed in his stead.

In Nobatae, south of Egypt, the inhabitants were converted to Miaphysite Christianity about 540. Justinian had been determined that they be converted to the Chalcedonian faith and Theodora equally determined that they should be Miaphysites. Justinian made arrangements for Chalcedonian missionaries from Thebaid to go with presents to Silko, the king of the Nobatae. But on hearing this, Theodora prepared her own missionaries and wrote to the duke of Thebaid that he should delay her husband's embassy, so that the Miaphysite missionaries should arrive first. The duke was canny enough to thwart the easygoing Justinian instead of the unforgiving Theodora. He saw to it that the Chalcedonian missionaries were delayed. When they eventually reached Silko, they were sent away, for the Nobatae had already adopted the Miaphysite creed of Theodosius.

Death

Theodora's death is recorded by Victor of Tonnena, with the cause uncertain but the Greek terms used are often translated as "cancer." The date was 28 June 548 at the age of 48.[26] Later accounts frequently attribute the death to breast cancer, although it was not identified as such in the original report where the use of the term "cancer" probably referred to "a suppurating ulcer or malignant tumor".[26] Other sources report that she died at 51.[27] Justinian wept bitterly at her funeral.[28] Her body was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles, in Constantinople.

Both Theodora and Justinian are represented in mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy, which was completed a year before her death.

Lasting influence

Her influence on Justinian was so strong that after her death he worked to bring harmony between the Monophysites and the Chalcedonian Christians in the Empire, and he kept his promise to protect her little community of Monophysite refugees in the Hormisdas Palace. Theodora provided much political support for the ministry of Jacob Baradaeus, and apparently personal friendship as well. Diehl attributes the modern existence of Jacobite Christianity equally to Baradaeus and to Theodora.[29]

Olbia in Cyrenaica renamed itself Theodorias after Theodora. (It was a common event that ancient cities renamed themselves to honor an emperor or empress.) The city, now called Qasr Libya, is known for its splendid sixth-century mosaics.

Media portrayals

Art

- The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Theodora.[30]

Books

- The Glittering Horn: Secret Memoirs of the Court of Justinian. Pierson Dixon (1958). A historical novel about the court of Justinian with Theodora playing a central part.

- Count Belisarius. Robert Graves. A historical novel by the author of I, Claudius which features Theodora as a character.

- The Purple Shroud. Stella Duffy (2012). A historical novel, about Theodora's years as empress.

- Theodora: Actress, Empress, Whore. Stella Duffy (2010). A historical novel, about Theodora's years up until she became empress.

- The Secret History: A Novel of Empress Theodora. Stephanie Thornton (2013). A historical novel, about Theodora's rise to empress.

- The Bearkeeper's Daughter. Gillian Bradshaw (1987). A young man out of Theodora's past arrives at the palace, seeking the truth of certain statements made to him by his dying father.

- Theodora and The Emperor. Harold Lamb (1952). Historical novel that focuses on the life of Theodora, her relationship with Justinian, and her many accomplishments as Empress.

- The Sarantine Mosaic. Guy Gavriel Kay (1998). Historical fantasy modelled on the Byzantium empire and the story of Justinian and Theodora.

- In the historical mystery novel One for Sorrow by Mary Reed/Eric Mayer, Theodora is one of the suspects in the murder case investigated by John, the Lord Chamberlain.

- In one of the episodes of Hendrik Willem van Loon's 1942 fantasy novel Van Loon's Lives, Empress Theodora is able to return to earth and spend one evening in a 20th provincial town, where she gets to meet Queen Elizabeth I of England, and where the book's narrator dances with her and falls a bit in love with her.

'The Female' {Paul Wellman} The rise of Theodora from prostitute to empress.[citation needed]

Film

- Teodora imperatrice di Bisanzio (Short, 1909) aka Theodora, Empress of Byzantium. Directed by Ernesto Maria Pasquali.

- Teodora, imperatrice di Bisanzio (1954) aka Theodora, Slave Empress. Directed by Riccardo Freda. Theodora played by Gianna Maria Canale.

- Kampf um Rom (1968) directed by Robert Siodmak, Sergiu Nicolaescu and Andrew Marton. In this movie she is played by Sylva Koscina.

Theater

- Theodora, A Drama. (1884), a play by Victorien Sardou.

- "Theodora: An Unauthorized Biography" (1994) a play by Jamie Pachino.[31][32][33][34]

Video games

- Theodora is the leader for the Byzantines in the video game Civilization V in its Gods and Kings expansion.

- Theodora gives missions to Belisarius, the main character in the Last Roman DLC for Total War: Attila.

Music

- The progressive rock band Big Big Train sings of Theodora herself, and the mosaics of Theodora and Justinian in Ravenna, in the song "Theodora in Green and Gold" on their 2019 album Grand Tour

Notes

- ^ Becoming visible : women in European history. Bridenthal, Renate., Koonz, Claudia., Stuard, Susan Mosher. (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1987. p. 132. ISBN 978-0395419502. OCLC 15714486.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Roman Emperors – DIR Theodora". roman-emperors.org.

- ^ a b Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, vol. 3, ed. J. Martindale. 1992.

- ^ a b Garland, p. 13.

- ^ Michael Grant. From Rome to Byzantium: The Fifth Century A.D., Routledge, p. 132

- ^ James Allan Evans (2011). The Power Game in Byzantium: Antonina and the Empress Theodora. A&C Black. p. 9. ISBN 978-1441120403.

- ^ The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire 2 Volume Set., J. R. Martindale, 1992 Cambridge University Press, p. 1240

- ^ Garland, p. 11.

- ^ Anderson, Zinsser, Bonnie, Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-06-015850-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Claudine M. Dauphin (1996). "Brothels, Baths and Babes: Prostitution in the Byzantine Holy Land". Classics Ireland. 3: 47–72. doi:10.2307/25528291. JSTOR 25528291.

- ^ Procopius, Secret History 9

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Diehl, Charles. Theodora, Empress of Byzantium ((c) 1972 by Frederick Ungar Publishing, Inc., transl. by S.R. Rosenbaum from the original French Theodora, Imperatrice de Byzance), 69–70.

- ^ Diehl, Charles (1963). Byzantine Empresses. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ Anderson & Zinsser, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 47.

- ^ Dielh, ibid.

- ^ Safire, William, ed, Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1992, p. 37

- ^ William Safire, Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History, Rosetta Books

- ^ Diehl, ibid.

- ^ Laura Swan, The Forgotten Desert Mothers (2001, ISBN 0809140160), pp. 72–73

- ^ Anne Commire, Deborah Klezmer. Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia (1999, ISBN 0787640808), p. 274.

- ^ Anderson & Zinsser, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 48.

- ^ Garland. Page 18.

- ^ Anderson & Zinssen, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 48.

- ^ "Theodora – Byzantine Empress". About.com. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ a b Harding, Fred (2007). Breast Cancer. ISBN 978-0955422102.

- ^ Anderson & Zinsser, Bonnie & Judith (1988). A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, Vol 1. New York: Harper & Row. p. 48.

- ^ Diehl, ibid., p. 197.

- ^ Diehl, ibid., p. 184.

- ^ Place Settings. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

- ^ Jamie Pachino. "Reviews and Press". www.jamiepachino.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Helbig, Jack. "Theodora: An Unauthorized Biography". chicagoreader.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Claycomb, Ryan (2012). Lives in Play: Autobiography and Biography on the Feminist Stage. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472118403. Retrieved 5 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Theodora: An Unauthorized Biography". indianapublicmedia.org. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

References

- Hans-Georg Beck: Kaiserin Theodora und Prokop: der Historiker und sein Opfer. Munich 1986, ISBN 3-492-05221-5.

- Henning Börm: Procopius, his predecessors, and the genesis of the Anecdota: Antimonarchic discourse in late antique historiography. In: Henning Börm (ed.): Antimonarchic discourse in Antiquity. Stuttgart 2015, pp. 305–346.

- James A. S. Evans: The empress Theodora. Partner of Justinian. Austin 2002.

- James A. S. Evans: The Power Game in Byzantium. Antonina and the Empress Theodora. London 2011.

- Lynda Garland: Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204. London 1999.

- Hartmut Leppin: Theodora und Iustinian. In: Hildegard Temporini-Gräfin Vitzthum (ed.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms. Von Livia bis Theodora. Munich 2002, pp. 437–481.

- Mischa Meier: Zur Funktion der Theodora-Rede im Geschichtswerk Prokops (BP 1,24,33-37)[permanent dead link]. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147 (2004), pp. 88ff.

- David Potter: Theodora. Actress, Empress, Saint. Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-974076-5.

- Procopius, The Secret History at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Procopius, The Secret History at LacusCurtius

External links

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- 500 births

- 548 deaths

- 6th-century Byzantine people

- 6th-century Byzantine women

- 6th-century Christian saints

- Ancient actresses

- Augustae

- Burials at the Church of the Holy Apostles

- Byzantine empresses

- Courtesans of antiquity

- Deaths from cancer

- Christian royal saints

- Feminism and history

- Greek and Roman dancers

- Greek Cypriot people

- Justinian dynasty

- Justinian I