There There (novel)

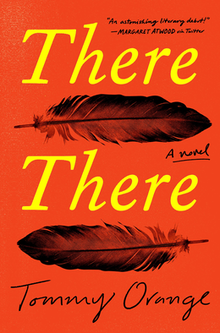

First edition cover | |

| Author | Tommy Orange |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Darrell Dennis[1] Shaun Taylor-Corbett[1] Alma Cuervo[1] Kyla Garcia[1] |

| Cover artist | Tyler Comrie (design)[2] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | history, fiction[3] |

| Set in | Oakland, California |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf |

Publication date | June 5, 2018 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 304 |

| Awards | |

| ISBN | 978-0-525-52037-5 |

| 813/.6 | |

| LC Class | PS3615.R32 T48 2018 |

There There is the debut novel by Cheyenne and Arapaho author Tommy Orange. Published in 2018, the book follows a large cast of Native Americans living in the Oakland, California area and contains several essays on Native American history and identity. The characters struggle with a wide array of challenges, ranging from depression and alcoholism, to unemployment, fetal alcohol syndrome, and the challenges of living with an "ambiguously nonwhite" ethnic identity in the United States. All of the characters unite at a community powwow and its attempted robbery.

The book explores the themes of Native peoples living in urban spaces (Urban Indians), and issues of ambivalence and complexity related to Natives' struggles with identity and authenticity. There There was favorably received, and was a finalist for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize.[4] The book was also awarded a Gold Medal for First Fiction by the California Book Awards.

Orange's second novel, Wandering Stars, was published in February 2024 as serves as both a prequel and sequel to There There.

Plot

[edit]The book begins with an essay by Orange, detailing "brief and jarring vignettes revealing the violence and genocide that Indigenous people have endured, and how it has been sanitized over the centuries."[5]

As the novel continues into fiction it alternates between first, second, and third person perspectives, following twelve characters who are Native American or closely related to Native Americans in the area of Oakland, California.[6][7][a] The main characters include Tony Loneman, Dene Oxendene, Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, Edwin Black, Bill Davis, Calvin Johnson, Jacquie Red Feather, Orvil Red Feather, Octavio Gomez, Daniel Gonzales, Blue, and Thomas Frank.

The characters face similar conflict throughout the novel. A teenager, Orvil Red Feather, turns to Google in search of the answer of the question of "What does it mean to be a real Indian,"[7] and in the mirror, wearing tribal regalia, sees only "a fake, a copy, a boy playing dress-up."[9] Calvin Johnson confronts his guilt at claiming to not be Native at all, admitting, "Mostly I just feel like I'm from Oakland."[7] One character struggles with his place in society as "ambiguously nonwhite," while another "overweight and constipated, has a graduate degree in Native American literature but no job prospects — a living symbol of the moribund plight of Indian culture in the United States."[6] Thomas, who is an alcoholic and has lost his job working as a janitor, wrestles with a life lived suspended between his mother, who is white, and his "one-thousand-percent Indian" father who is a medicine man.[6] Orange writes:

You're from a people who took and took and took and took. And from a people taken. You're both and neither. In the bath, you'd stare at your brown arms against your white legs in the water and wonder what they were doing together on the same body, in the same bathtub.[10]

Tony Loneman grapples with the fetal alcohol syndrome left to him by his alcoholic mother. Octavio Gomez remembers alcohol through the drunk driving incident that claimed his family. Jacquie Red Feather faces sobriety from the perspective of a substance abuse counselor in the wake of her daughter's suicide thirteen years prior.[7] Blue recalls how she initially remained with her abusive partner before finally leaving.[11] Jacquie and her half-sister Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield recall their childhood experiences in the Native American occupation of Alcatraz island.

All storylines and characters eventually coalesce around a powwow taking place at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, where some characters have smuggled in 3D printed handguns in an attempt to rob the event to repay drug debts.[6][8]

Themes

[edit]We did not move to cities to die. The sidewalks and streets, the concrete absorbed our heaviness. The glass, metal, rubber, and wires, the speed, the hurtling masses — the city took us in. This was part of the Indian Relocation Act, which was part of the Indian Termination Policy, which was and is exactly what it sounds like. Make them look and act like us. Become us. And so disappear. But it wasn't just like that. Plenty of us came by choice, to start over, to make money, or for a new experience. Some of us came to cities to escape the reservation. We stayed . . .

Tommy Orange, There There, prologue

Orange, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, was raised in the Oakland area.[12]

The title of the novel (despite taking note of the song "There There" by English rock band Radiohead in the second chapter) is a reference to Gertrude Stein's own description, in her 1937 Everybody's Autobiography, of an attempt to return to her childhood home in Oakland but finding that the rural Oakland she remembered was gone: "There is no there there."[5][8] For Native people, Orange writes that cities and towns represent "buried ancestral land, glass and concrete and wire and steel, unreturnable covered memory. There is no there there."[5]

Alcatraz Island and its prison also serves as a meaningful location in the novel: a desolate institution that had no running fresh water and no electricity; these conditions were used as an example comparable to the conditions that many Native American reservations faced. The character Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, her half-sister Jacquie, and their mother Vicky, were on Alcatraz during the Native American Occupation of Alcatraz.[13]

Writing in The New York Times, Alexandra Alter described the book in terms of ambivalence and complexity, quoting Orange, himself a graduate of the Institute of American Indian Arts, born to a Cheyenne father and white mother who converted to evangelical Christianity and denounced his father's spiritual beliefs, "I wanted to have my characters struggle in the way that I struggled, and the way that I see other native people struggle, with identity and with authenticity."[5]

Reception

[edit]

According to Book Marks, the book received "rave" reviews based on twenty-four critic reviews with twenty-one being "rave" and three being "positive".[14] In Books in the Media, a site that aggregates critic reviews of books, the book received a ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.92 out of 5) from the site which was based on four critic reviews.[15] On Bookmarks September/October 2020 issue, a magazine that aggregates critic reviews of books, the book received a

(4.92 out of 5) from the site which was based on four critic reviews.[15] On Bookmarks September/October 2020 issue, a magazine that aggregates critic reviews of books, the book received a ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.0 out of 5) based on critic reviews.[16][17]

(4.0 out of 5) based on critic reviews.[16][17]

The Globe and Mail described There There, saying that it "should probably be on reading lists for every creative writing program in this country," and commended it as "stunning," with "effective, masterful execution."[11] The New York Times praised Orange's "extraordinary ability" and described the novel as "a tense, prismatic book with inexorable momentum."[18] According to the Sydney Morning Herald, Orange brings "authority and intelligence" to the stories of his characters: In the novel, "[d]islocation and grief are constant, yet again and again we encounter resistance and resilience."[19] Publishers Weekly summarized the work as "breathtaking" and a "haunting and gripping story,"[20] while The Millions dubbed it "one of our most anticipated books of the year."[21] The National Book Review called There There "spectacular," "a work of fiction of the highest order," landing "on the shores of a world that should be abashed it was unaware it had been awaiting his arrival."[3]

Canadian writer Margaret Atwood praised the work as "an astonishing literary debut."[22] Egyptian-Canadian novelist and journalist Omar El Akkad wrote:

There There is a miraculous achievement, a book that wields ferocious honesty and originality in service of telling a story that needs to be told. This is a novel about what it means to inhabit a land both yours and stolen from you, to simultaneously contend with the weight of belonging and unbelonging. There is an organic power to this book—a revelatory, controlled chaos. Tommy Orange writes the way a storm makes landfall.[23]

Speaking of the opening essay of the book, Ron Charles of The Washington Post described it as "white-hot," as Orange "rifles through our national storehouse of atrocities and slurs," in a piece that begs not be passed over when compiling the year's list of "The Best American Essays."[6] The San Francisco Chronicle described the prologue as "so searing that it set off a four-day publisher bidding war for reasons that are immediately apparent."[7] Orange described his prologue as "a prayer from hell" in an interview with BuzzFeed, who for their own part, summarized it as "a sort of urban Native manifesto, a mini history, a prologue so good it leaves the reader feeling woozy, or concussed."[24]

There There was shortlisted for the 2019 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.[25] It won the 2018 National Book Critics Circle Award's "John Leonard Prize" for the first book by a new voice[26] and the 2019 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award.[27]

Sales

[edit]There There reached number one on the San Francisco Chronicle’s best-seller list, and number eight on The New York Times Best Seller list.[28]

Sequel

[edit]Wandering Stars, Orange's second novel, was published in February 2024. Orange described the novel as "kind of prequel and sequel, having historical aspects as well as following up on the aftermath(s) of the culminating event in There There."[29][30]

See also

[edit]- Sherman Alexie, Spokane-Coeur d'Alene-American novelist, short story writer, poet, and filmmaker

- Layli Long Soldier, an Oglala Lakota poet, writer and artist

- Louise Erdrich, American author of novels, poetry, and children's books featuring Native American characters and settings

- Terese Marie Mailhot, a First Nation Canadian writer, journalist, memoirist, and teacher

- List of writers from peoples indigenous to the Americas

Notes

[edit]- ^ So-called, "urban Indians"[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "There There by Tommy Orange". Penguin Random House Audio. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Temple, Emily (December 7, 2018). "Who Wore It Best? US Book Covers vs. UK Book Covers for 2018". Literary Hub. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ a b McGee, Celia (June 2018). "Review: A Spectacular New Novel that Wants Native Americans to be Seen". The National Book Review. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ "Winners & Finalists for the 2019 Pulitzer Prize". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Alter, Alexandra (May 31, 2018). "With 'There There,' Tommy Orange Has Written a New Kind of American Epic". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Charles, Ron (May 29, 2018). "What does it mean to be Native American? A new novel offers a bracing answer". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Leu, Chelsea (June 6, 2018). "'There There,' by Tommy Orange". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c Garner, Dwight (June 4, 2018). "'There There' is an Energetic Revelation of a Corner of American Life". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Baker, Jeff (June 3, 2018). "'There There' gives voice to the Native urban experience". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Orange, Tommy (March 26, 2018). "The State". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Elliot, Alicia (June 5, 2018). "Review: Tommy Orange's stunning debut novel There There". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Jeff. "TOMMY ORANGE in Conversation with Jeff Chang". City Arts & Lectures. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ Lanigan, Julia. "LibGuides: There There: Home". libguides.mit.edu. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ "There There". Book Marks. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ "There There Reviews". Books in the Media. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "There There". Bookmarks. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "There There". Bibliosurf (in French). October 4, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 17, 2018). "17 Refreshing Books to Read This Summer". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Bradley, James (September 6, 2019). "There There review: Tommy Orange's brilliant debut about urban Native Americans". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ "There There". Publishers Weekly. April 2, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Valderrama, Ariana (June 2, 2018). "A New Native American Epic". The Millions. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Canfield, David (June 4, 2018). "Meet Tommy Orange, author of the year's most galvanizing debut novel". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ "Upcoming Event: Tommy Orange". Harvard Book Store. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Petersen, Anne Helen (February 22, 2018). "These Writers Are Launching A New Wave Of Native American Literature". BuzzFeed. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ "ALA Unveils 2019 Carnegie Medals Shortlist". American Libraries. October 24, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Hillel Italie (March 14, 2018). "Zadie Smith, Anna Burns among winners of critics prizes". The Washington Post. The Associated Press. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ "Breakout Novelist Tommy Orange Wins $25,000 PEN/Hemingway Award for There There". PEN America. March 19, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ McMurtrie, John (July 11, 2018). "Instant smash hit for Tommy Orange's first novel, about Indians in Oakland". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Literary Agent Nicole Aragi

- ^ "Stopping by with Tommy Orange". Poetry Society of America. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- The State, a chapter from There There, published March 26, 2018, in The New Yorker, including audio as read by Tommy Orange

- Interview with Tommy Orange, published March 19, 2018, in The New Yorker

- Book Review of There There published March 20, 2018, by Kirkus Reviews

External links

[edit]- Neary, Lynn (June 7, 2018). "Tommy Orange's 'There There' Has A Wide Cast Of Native American Characters (audio)". National Public Radio. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- Orange, Tommy (June 19, 2018). "A letter from Tommy Orange, author of There There". Goldboro Books. Retrieved August 9, 2018.