Thyroiditis

| Thyroiditis | |

|---|---|

| |

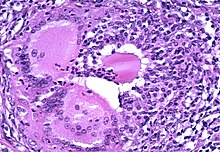

| Above shows two parts of the thyroid that could potentially be affected if diagnosed with thyroiditis. | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Thyroiditis is the inflammation of the thyroid gland. The thyroid gland is located on the front of the neck below the laryngeal prominence, and makes hormones that control metabolism.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]There are many different signs and symptoms for thyroiditis, none of which are exclusively limited to this disease. Many of the signs imitate symptoms of other diseases, so thyroiditis can sometimes be difficult to diagnose. Common hypothyroid symptoms manifest when thyroid cell damage is slow and chronic, and may include fatigue, weight gain, feeling "fuzzy headed", depression, dry skin, and constipation. Other, rarer symptoms include swelling of the legs, vague aches and pains, decreased concentration and so on. When conditions become more severe, depending on the type of thyroiditis, one may start to see puffiness around the eyes, slowing of the heart rate, a drop in body temperature, or even incipient heart failure. On the other hand, if the thyroid cell damage is acute, the thyroid hormone within the gland leaks out into the bloodstream causing symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, which is similar to those of hyperthyroidism. These symptoms include weight loss, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, fast heart rate, and fatigue. Elevated levels of thyroid hormone in the bloodstream cause both conditions, but thyrotoxicosis is the term used with thyroiditis since the thyroid gland is not overactive, as in the case of hyperthyroidism.[1]

Causes

[edit]Thyroiditis is generally caused by an immune system attack on the thyroid, resulting in inflammation and damage to the thyroid cells. This disease is often considered a malfunction of the immune system and can be associated with IgG4-related systemic disease, in which symptoms of autoimmune pancreatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis and noninfectious aortitis also occur. Such is also the case in Riedel thyroiditis, an inflammation in which the thyroid tissue is replaced by fibrous tissue which can extend to neighbouring structures. Antibodies that attack the thyroid are what causes most types of thyroiditis. It can also be caused by an infection, like a virus or bacteria, which works in the same way as antibodies to cause inflammation in the glands, such as in the case of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis (de Quervain).[2] Certain people make thyroid antibodies, and thyroiditis can be considered an autoimmune disease, because the body acts as if the thyroid gland is foreign tissue.[3] Some drugs, such as interferon, lithium, amiodarone (AIT type-2) and immune check point inhibitors can also cause thyroiditis.[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]Diagnosis of thyroiditis depends on the specific cause and clinical context. When the initial presentation is thyrotoxicosis, work-up will include causes of thyroiditis as well as causes of hyperthyroidism. In some types of thyroiditis, a physical exam may reveal an enlarged thyroid and/or tenderness to palpation. If infectious thyroiditis is suspected a neck ultrasound can be utilized to check for an abscess. Color flow doppler is expected to show reduced blood flow in thyroiditis vs. hyperthyroidism.[5] Blood tests will usually include thyroid function tests as well levels of specific thyroid antibodies and thyroglobulin. Inflammatory markers such as white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and c-reactive protein may be elevated in some forms of thyroiditis. The gold-standard for diagnosis of thyroiditis is the lack of tracer uptake in a radionuclide uptake scan such as radioactive iodine, technetium-99m or setamibi.[6] Importantly, recent exposure to an intravenous iodine based radio-contrast agent may lead to falsely low uptake due to saturation with iodine.[7]

Classification

[edit]

Thyroiditis is a group of disorders that all cause thyroidal inflammation. Forms of the disease are Hashimoto's thyroiditis, the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the US, postpartum thyroiditis, subacute thyroiditis, silent thyroiditis, drug-induced thyroiditis, radiation-induced thyroiditis, acute thyroiditis, Riedel's thyroiditis.[8]

Treatment

[edit]Treatments for this disease depend on the type of thyroiditis that is diagnosed. For the most common type, which is known as Hashimoto's thyroiditis, the treatment is to immediately start hormone replacement. This prevents or corrects the hypothyroidism, and it also generally keeps the gland from getting bigger. However, Hashimoto's thyroiditis can initially present with excessive thyroid hormone being released from the thyroid gland (hyperthyroid). In this case the patient may only need bed rest and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications; however, some need steroids to reduce inflammation and to control palpitations. Also, doctors may prescribe beta blockers to lower the heart rate and reduce tremors, until the initial hyperthyroid period has resolved.[9]

Epidemiology

[edit]Most types of thyroiditis are three to five times more likely to be found in women than in men. The average age of onset is between thirty and fifty years of age. This disease tends to be geographical and seasonal, and is most common in summer and fall.[1]

History

[edit]Hashimoto's thyroiditis was first described by Japanese physician Hashimoto Hakaru working in Germany in 1912. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, and patients with this disease often complain about difficulty swallowing. This condition may be so mild at first that the disease goes unnoticed for years. The first symptom that shows signs of Hashimoto's thyroiditis is a goiter on the front of the neck. Depending on the severity of the disease and how much it has progressed, doctors then decide what steps are taken for treatment.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Patel DS (June 2023). "Thyroiditis". Familydoctor.org. American Academy of Family Physicians. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ De Groot LJ, Nobuyuki A, Takashi A. "Hashimoto's Thryoiditis". TDM. Thyroid Disease Manager. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ Ferry R (8 September 2007). "Hashimoto's Thyroiditis Symptoms, Diet, and Treatments". MedicineNet. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Pollack R, Stokar J, Lishinsky N, Gurt I, Kaisar-Iluz N, Shaul ME, et al. (June 2023). "RNA Sequencing Reveals Unique Transcriptomic Signatures of the Thyroid in a Murine Lung Cancer Model Treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 Antibodies". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (13): 10526. doi:10.3390/ijms241310526. PMC 10341615. PMID 37445704.

- ^ Zhao X, Chen L, Li L, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhou L, et al. (2012). "Peak systolic velocity of superior thyroid artery for the differential diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50051. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750051Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050051. PMC 3500337. PMID 23166817.

- ^ Itzkovich D, Ben-Haim S, Godefroy J, Stokar J (January 2023). "99mTc MIBI Scintigraphy for Classification of Amiodarone-induced Thyrotoxicosis". JCEM Case Reports. 1 (1): luac011. doi:10.1210/jcemcr/luac011. PMC 10578384. PMID 37908259.

- ^ Vassaux G, Zwarthoed C, Signetti L, Guglielmi J, Compin C, Guigonis JM, et al. (January 2018). "Iodinated Contrast Agents Perturb Iodide Uptake by the Thyroid Independently of Free Iodide". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 59 (1): 121–126. doi:10.2967/jnumed.117.195685. PMID 29051343.

- ^ "Thyroiditis" (en). www.thyroid.org. American Thyroid Association. 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Ross D (November 2023). Cooper D (ed.). "Beta blockers in the treatment of hyperthyroidism". UpToDate. Waltham, MA: Wolters Kluwer. Retrieved 27 July 2017.