Titus Andronicus: Difference between revisions

→Synopsis: add link relevant to plot |

Tag: blanking |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

[[File:Titus Andronicus.jpg|thumb|200px|Lavinia showing her father how she may be able to reveal her rapists' identities.]] |

|||

The Emperor of Rome has died and his sons Saturninus and Bassianus are squabbling over who will succeed him. The [[Tribune|Tribune of the People]], Marcus Andronicus, announces that the people's choice for new emperor is his brother, Titus Andronicus, a Roman general newly returned from ten years' campaigning against the empire's foes, the [[Goths]]. Titus enters Rome to much fanfare, bearing with him Tamora, Queen of the Goths, her sons, and Aaron the [[Moors|Moor]] (lover to Tamora). Titus feels a religious duty to sacrifice Tamora’s eldest son, Alarbus, in order to avenge his sons, dead from the war, and allow them to rest in peace. Tamora begs for the life of Alarbus, but Titus refuses her pleas. Tamora secretly plans a horrible revenge for Titus and all of his remaining sons. |

|||

Titus Andronicus refuses the throne but is requested to choose between Bassianus and Saturninus, the late emperor's sons - he decides upon the elder, Saturninus, much to Saturninus' delight. As a favour to Titus and his family, Saturninus then chooses Titus' daughter, Lavinia, as his queen. However, Bassianus was previously [[betrothal|betrothed]] to the girl. Titus' surviving sons rescue Lavinia and escape from the scene with her. Titus ruthlessly kills his son, Mutius, while trying to get her back - he is angry with his sons because in his eyes they have dishonoured the State of Rome by disobeying the Emperor. Saturninus throws Titus out of his favour and decides to marry Tamora instead. |

|||

The next day Aaron the Moor, Tamora's lover, discovers Chiron and Demetrius arguing over which of them loves Lavinia more and who should take sexual advantage of her. They are easily persuaded by Aaron to ambush Bassianus later that day during a hunting party in the woods and to kill him in the presence of Tamora and Lavinia, then rape Lavinia. Lavinia begs Tamora to stop her sons, but Tamora refuses. Chiron and Demetrius throw Bassianus' body in a pit, as Aaron had directed them, then they take Lavinia away and [[rape]] her. To keep her from revealing what she has seen and endured, they cut out her tongue and cut off her hands. This mutilation references the classical story of Philomel, who was raped and then had her tongue cut out to prevent her revealing her attacker's identity. The story is referred to several times by the characters in 'Titus' as a parallel to Lavinia's fate. |

|||

[[File:Ira Aldridge as Aaron in Titus Andronicus.jpg|thumb|left|200px|African-American actor [[Ira Aldridge]] as Aaron threatens those who would harm his son. Circa 1852.]] |

|||

Aaron brings Titus' sons Martius and Quintus to the scene and frames them for the murder of Bassianus with a forged letter outlining their plan to kill him. Angry, the Emperor arrests them. Marcus then discovers Lavinia and takes her to her father. When she and Titus are reunited, he is overcome with grief. He and his remaining son Lucius have begged for the lives of Martius and Quintus, but the two are found guilty and are marched off to execution. Aaron enters, and falsely tells Titus, Lucius, and Marcus that the emperor will spare the prisoners if one of the three sacrifices a hand. Each demands the right to do so, but it is Titus who has Aaron cut off his (Titus') hand and take it to the emperor. In return, a messenger brings Titus the heads of his sons and his own severed hand. Desperate for revenge, Titus orders Lucius to flee Rome and raise an army among their former enemy, the Goths. |

|||

Later, Titus' grandson (Lucius' son), who has been helping Titus read to Lavinia, complains that she will not leave his book alone. In the book, she indicates to Titus and Marcus the story of [[Philomela (princess of Athens)|Philomela]], in which a similarly mute victim "wrote" the name of her wrongdoer. Marcus gives her a stick to hold with her mouth and stumps and she writes the names of her attackers in the dirt. Titus vows revenge. Feigning madness, he ties written prayers for justice to arrows and commands his kinsmen to aim them at the sky. Marcus directs the arrows to land inside the palace of Saturninus, who is enraged by this. He confronts the Andronici and orders the execution of a Clown who had delivered a further supplication from Titus. |

|||

Tamora delivers a mixed-race child, and the nurse can tell it must have been fathered by Aaron. Aaron kills the nurse and flees with the baby to save it from the Emperor's inevitable wrath. Later, Lucius, marching on Rome with an army, captures Aaron and threatens to hang the infant. To save the baby, Aaron reveals the entire plot to Lucius, relishing his retelling of every murder, rape, and dismemberment. |

|||

Tamora, convinced of Titus' madness, approaches him along with her two sons, dressed as the spirits of Revenge, Murder, and Rape. She tells Titus that she (as a supernatural spirit) will grant him revenge if he will convince Lucius to stop attacking Rome. Titus agrees, sending Marcus to invite Lucius to a feast. "Revenge" (Tamora) offers to invite the Emperor and Tamora, and is about to leave, but Titus insists that "Rape" and "Murder" (Chiron and Demetrius) stay with him. She agrees. When she is gone Titus' servants bind Chiron and Demetrius, and Titus cuts their throats, while Lavinia holds a basin in her stumps to catch their blood. He plans to cook them into a pie for their mother. This is the same revenge [[Procne]] took for the rape of her sister Philomela. |

|||

The next day, during the feast at his house, Titus asks Saturninus whether a father should kill his daughter if she has been raped.<ref>Citing the story of [[Verginia]], told in [[Livy]].</ref> When the Emperor agrees, Titus then kills Lavinia and tells Saturninus what Tamora's sons had done. When the Emperor asks for Chiron and Demetrius, Titus reveals that they were in the pie Tamora has just been enjoying, and then kills Tamora. Saturninus kills Titus just as Lucius arrives, and Lucius kills Saturninus to avenge his father's death. |

|||

Lucius tells his family's story to the people and is proclaimed Emperor. He orders that Saturninus be given a proper burial, that Tamora's body be thrown to the wild beasts, and that Aaron be buried chest-deep and left to die of [[thirst]] and starvation. Aaron, however, is unrepentant to the end, proclaiming: |

Lucius tells his family's story to the people and is proclaimed Emperor. He orders that Saturninus be given a proper burial, that Tamora's body be thrown to the wild beasts, and that Aaron be buried chest-deep and left to die of [[thirst]] and starvation. Aaron, however, is unrepentant to the end, proclaiming: |

||

Revision as of 04:13, 10 November 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Titus Andronicus is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It may be Shakespeare's earliest tragedy; it is believed to have been written in the early 1590s. It depicts a Roman general who is engaged in a cycle of revenge with his enemy Tamora, the Queen of the Goths. The play is by far Shakespeare's bloodiest work. It lost popularity during the Victorian era because of its gore, and it has only recently seen its fortunes revive.

Characters

|

|

Synopsis

Lucius tells his family's story to the people and is proclaimed Emperor. He orders that Saturninus be given a proper burial, that Tamora's body be thrown to the wild beasts, and that Aaron be buried chest-deep and left to die of thirst and starvation. Aaron, however, is unrepentant to the end, proclaiming:

"If one good Deed in all my life I did,

I do repent it from my very Soule."

Date and text

Most scholars date the play to the early 1590s. In his Arden edition, Jonathan Bate proposes that the play was written in late 1593, pointing out that on 24 January 1594 it was apparently listed as a new play in Philip Henslowe's diary. Another school of opinion has doubted the play's newness in 1594, given that the induction of Ben Jonson's Bartholomew Fair (1614) seems to suggest that Titus Andronicus was then about 25 years old, which would date it to ca. 1589.[1] The Norton/Sackville play Gorboduc, originally a play from the 1560s, was published again in 1590. Its many similarities with Titus Andronicus favor an earlier date for the composition of Titus Andronicus because Shakespeare may have read it in or just after 1590. Shakespeare may even have acted in Gorboduc at a somewhat earlier date.[2]

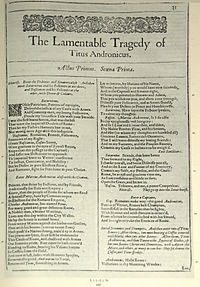

The play was published in three separate quarto editions prior to the First Folio of 1623, which are referred to as Q1, Q2, and Q3 by Shakespeare scholars. The play was entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 6 February 1594, by the printer John Danter. Danter sold the rights to the booksellers Thomas Millington and Edward White; they issued the first quarto edition (Q1) later that year, with printing done by Danter. The title page is unusual in that it assigns the play to three different companies of actors—Pembroke's Men, Derby's Men, and Sussex's Men. White published Q2 in 1600 (printed by James Roberts), and Q3 in 1611 (printed by Edward Allde). The First Folio text (1623) was printed from Q3 with an additional scene, III, ii.

Q1 is regarded as a reasonably "good" (complete and reliable) text, and is the basis for most modern editions, although it does not include some material found in the First Folio. Only a single copy is known to exist today. Q2 appears to be based on a damaged copy of Q1, as it is a good reproduction of the Q1 text, but is missing a number of lines. Two copies are known to exist today. Q3 appears to be a further degradation of the Q2 text: it includes a number of corrections to Q2, but introduces even more errors. The First Folio text of 1623 seems to be based on the Q3 text, but also includes material found in none of the quarto editions, including the entirety of Act 3, Scene 2 (in which Titus seems to be losing his sanity). This scene is generally regarded as authentic and included in modern editions of the play.

None of the three quarto editions name the author (as was normal in the publication of playtexts in the early 1590s). However, Francis Meres lists the play as one of Shakespeare's tragedies in a publication of 1598, and the editors of the First Folio included it among his works. Despite this, Shakespeare's full authorship has been doubted. In the introduction to his 1678 adaptation of the play (printed nine years later, in 1687), Edward Ravenscroft states: "I have been told by some anciently conversant with the Stage, that it was not Originally his, but brought by a private Author to be Acted, and he only gave some Master-touches to one or two Principal Parts or Characters".[3] There are problems with Ravenscroft's statement: the old men "conversant with the Stage" could not have been more than children whenTitus was written, and Ravenscroft may be biased, since he uses the story to justify his alterations of Shakespeare's play. However, the story has been used to bolster arguments that another author was partly responsible.

The principal candidate is the dramatist George Peele, whose linguistic characteristics have been detected in both the first act, and the scene in which Lavinia uses Ovid's Metamorphoses to explain that she has been raped.[4] The assertion of Peele's hand in the play remains controversial, however, and those who admire the play tend to argue against it.[5] It has even been posited that Shakespeare did not write Titus Andronicus at all; for example, the 19th century Globe Illustrated Shakespeare goes so far as to claim there was a general agreement on the matter due to the un-Shakespearean "barbarity" of the play's action.

Analysis and criticism

Reputation

As Shakespeare's most gruesome play, Titus Andronicus has also been his most derided.[citation needed] Critics from Lewis Theobald and Edmond Malone to J. M. Robertson doubted Shakespeare's authorship because of its lurid violence and generally uninspired verse.[citation needed] However, it was an extremely popular play in its day, on par with such plays as Marlowe's Tamburlaine and Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy.[citation needed]

Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom has claimed that the play cannot be taken seriously and that the best imaginable production would be one directed by Mel Brooks.[citation needed]

Structure

Written between 1589 and 1592, Titus Andronicus may be Shakespeare's earliest tragedy and is written in the form of a revenge tragedy. The play has characteristics similar to the work of Seneca, specifically his play Thyestes, which included horrific scenes of severed hands, cannibalism, and rape. Although violence was not uncommon in Elizabethan plays, Titus Andronicus stands out due to the volume and extremity of the violent acts committed. Unlike his other works, the play contains an uncanny number of crude and savage moments, which has sparked debate among critics as to whether or not the play was actually composed by Shakespeare. Nonetheless, Andronicus was not Shakespeare's only revenge tragedy, as his work Hamlet is considered one of the best examples of Elizabethan revenge tragedies. Julius Caesar and Macbeth also have elements of the revenge tragedy, albeit that none of these works contain the volume or the vivid descriptions of violence of Titus Andronicus.

Critic S. Clark Hulse even went as far as to calculate the number of atrocities occurring in the play and concluded that, “It (the play) has 14 killings, 9 of them on stage, 6 severed members, 1 rape (or 2 or 3 depending on how you count), 1 live burial, 1 case of insanity, and 1 of cannibalism—-an average of 5.2 atrocities per act, or one for every 97 lines.” The vivid descriptions that Shakespeare uses to describe these violent acts certainly stand out to critics. T. S. Eliot claimed that the play was the "worst play ever written" (Bate 27). Shakespearean critic Harold Bloom, in his work Shakespeare: Invention of the Human, says that Shakespeare must have intended the work as a parody of the violent plays of colleague Christopher Marlowe, who was writing at the same time as Shakespeare.

What stands out about the dramatic structure of the play is that unlike Shakespeare's other works, such as Romeo and Juliet which shifts between comedy and tragedy, Titus Andronicus continuously remains a revenge tragedy throughout. The play cannot be considered a history play, as it combines various names and events from different points in Roman history, such as the Lucrece story, and it is likely that Shakespeare would have been familiar with Ovid's work, Fasti or Livy's work The History of Rome. It has been noted by critics that the play contains very few subplots in contrast to other works by Shakespeare such as Twelfth Night and A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Language

The language of Titus Andronicus adds greatly to the grisly action of the play. Jack Reese notes that, as a result of its gruesome nature, the play is often disregarded "as an immature exercise in sensationalism" (78). He says that this is the fault of the readers who are unaware of the literary elements and techniques present throughout the work. Reese suggests that the horrific fates of the characters are not even so horrific because the characters lack any human quality that would lead the readers to identify with them. In the example of Lavinia, he refers to her as "an emblematic figure representing Injured Innocence" (79). There are greater implications to her brutal experience than what is simply written on the page. Reese mentions that the audience is further disconnected from the violence on stage through its various descriptions. The language used in these descriptions serves to "further emphasize the artificiality of the play; in a sense, they suggest to the audience that it is hearing a poem read rather than seeing the events of that poem put into dramatic form" (83). Peter Sacks comments on the imagery conveyed through the play’s language as marked by "an artificial and heavily emblematic style, and above all, a revoltingly grotesque series of horrors which seem to have little function but to ironize man's inadequate expressions of pain and loss" (587). Shakespeare's mastery of language stylizes the brutality seen in Titus Andronicus. Gillian Kendall follows a similar line of thought, stating that rhetorical devices, such as metaphor, augment the violent imagery, also elevating it. She discusses how the figurative use of certain words complements their literal counterparts. This, however, "disrupts the way the audience perceives imagery" (300). An example of this is seen in the body politic/dead body imagery in the beginning; the two images soon become interchangeable, as do others through the course of the play.

Critic Mary Fawcett looks not only at the language of the play, but also at language as a theme. She comments on the communication methods of Lavinia, post-rape, looking first at the term "scrowl" used by Demetrius in Act 2 Scene 4. Fawcett suggests that this word is a fusion of "scowl" and "scroll"; Demetrius “locates an area of language that is not spoken and not written” (261).

Themes

This Roman tragedy is based on the mythological story of Procne and Philomela found in Ovid's Metamorphoses. Alan Hughes, a Shakespearean critic, believes that Procne's revenge is a conspicuous theme in this Shakespearean play. Procne avenges the dismemberment of her sister Philomela, whose tongue is cut out after she is raped by Procne's husband Tereus, by killing her son and feeding him to her husband.[6] Just as Procne is driven by revenge, the characters in Titus Andronicus are driven by revenge fueling the rape and carnage that occurs throughout the play.[7]

Performance

Although Titus Andronicus is one of Shakespeare's earliest plays, it is hard to say exactly how early it is. The anonymous play A Knack to Know a Knave, acted in 1592, alludes to Titus and the Goths, which clearly indicates Shakespeare's play, since other versions of the Titus story involve Moors, not Goths. Philip Henslowe's diary records performances of a Titus and Vespasian in 1592–93, and some critics have identified this with Shakespeare's play.[8]

In January and February of 1594, Sussex's Men gave three performances of Titus Andronicus; two more performances followed in June of the same year, at the Newington Butts theatre, by either the Admiral's Men or the Lord Chamberlain's Men. A private performance occurred in 1596 at Sir John Harington's house in Rutland.

In the Restoration, the play was performed in 1678 at Drury Lane, in an adaptation by Edward Ravenscroft. The eighteenth-century actor James Quin considered Aaron, the villain in Titus, one of his favourite roles.[9]

Films

- The 1998 film Titus Andronicus, directed by Chris Dunne. Stars Bob Reese as Titus, and costars Tom Dennis, Levi-David Tinker, Candy K. Sweet and Lexton Raleigh.

- Titus (1999), directed by Julie Taymor. Stars Anthony Hopkins and Jessica Lange as Titus and Tamora, respectively.

- Titus Andronicus (1985): a TV movie directed by Jane Howell, last of the BBC Shakespeare series. Stars Trevor Peacock and Eileen Atkins as Titus and Tamora, with Hugh Quarshie as Aaron.

Adaptations

- Die Schändung by German author Botho Strauss

- Titus Andronicus. Komödie nach Shakespeare by Swiss author Friedrich Dürrenmatt

- Anatomie Titus Fall of Rome. Ein Shakespearekommentar, a 1984 play by (East) German author Heiner Müller

- Titus Andronicus: The Musical!, written by Brian Colonna, Erik Edborg, Hannah Duggan, Erin Rollman, Matt Petraglia, and Samantha Schmitz, was staged by the Buntport Theater of Denver, Colorado three times between 2005 and 2007.[citation needed]

- The Reduced Shakespeare Company rendered Titus Andronicus as a cooking show and referred to the time of its writing as Shakespeare's "Quentin Tarantino phase".

- Tragedy! A Musical Comedy, written by Michael Johnson and Mary Davenport was performed at the 2007 New York International Fringe Festival.[citation needed]

- The Spanish theatre company La Fura dels Baus has adapted the play as 'La Degustación de Titus Andrónicus' in 2010.[citation needed]

- Tamora appears as either an outlaw or resistance fighter in the IDW comics series Kill Shakespeare, in its second issue. Thus far, she has not reappeared in this series.

Notes

- ^ Bate, Titus, 72.

- ^ Gorboduc and Titus Andronicus; James D. Carroll, Notes and Queries, 2004, 51, 267-269.

- ^ Quoted in Jonathan Bate, ed. Titus Andronicus (Arden Shakespeare, 1996), p. 79

- ^ Brian Vickers, Shakespeare: Co-Author (Oxford University Press, 2004) describes the history of this attribution and adds more evidence of his own.

- ^ For a summary of this debate, see Bate, Titus, p. 79-83.

- ^ Ovid 230

- ^ Shakespeare 1070–1096

- ^ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; pp. 496–97.

- ^ Halliday, Shakespeare Companion, pp. 399, 403, 497.

References

- Bate, Jonathan. Titus Andronicus. Cengage Learning Publishing. March, 1995. pp. 25–29.

- Bloom, Harold. Shakespeare The Invention of the Human. New York Publishing Company. New York. 1998

- Bullough, Geoffrey. Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare. New York, Columbia University Press, 1966.

- Cutts, John P. The Shattered Glass: A Dramatic Pattern in Shakespeare's Early Plays. Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1968.

- Dowden, Edward. Shakespeare: A Critical Study of His Mind and Art. New York, Barnes & Noble ING, 1967.

- Fawcett, Mary Laughlin. “Arms/Words/Tears: Language and the Body in Titus Andronicus”. ELH 50.2 (1983): 261–277.

- Gray, Henry David. "Titus Andronicus Once More". Modern Language Notes, Vol. 32, No. 4 (April 1919) pp. 214–220.

- Hughes, Derek (2007). Culture and Sacrifice: Ritual Death in Literature and Opera. Cambridge University Press. pp. 68–74. ISBN 978-0-521-86733-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kendall, Gillian Murray. “‘Lend me thy hand’: Metaphor and Mayhem in Titus Andronicus”. Shakespeare Quarterly 40.3 (1989): 299–316.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses. Trans. David Raeburn. London: Penguin Books, 2004.

- Reese, Jack E. “The Formalization of Horror in Titus Andronicus”. Shakespeare Quarterly 21.1 (1970): 77–84.

- Sacks, Peter. “Where Words Prevail Not: Grief, Revenge, and Language in Kyd and Shakespeare”. ELH 49.3 (1982): 576–601.

- Shakespeare, William. The Lamentable Tragedy of Titus Andronicus. Ed. Baildon, Bellyse. London: Methuen and Co, 1904.

- Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. Ed. Alan Hughes. London: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Shakespeare, William. The Riverside Shakespeare: Second Edition. Ed. Dean Johnson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1997.

- Willis, Deborah. "The gnawing vulture: Revenge, Trauma Theory, and Titus Andronicus". Shakespeare Quarterly 53.1 (2002): 21–52.

External links

- Titus Andronicus – plain text from Project Gutenberg.

- Lucius, the Severely Flawed Redeemer of Titus Andronicus by Anthony Brian Taylor.