Ulster Special Constabulary

| Ulster Special Constabulary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common name | B Specials |

| Abbreviation | USC |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | October 1920 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Dissolved | 31 March 1970 |

| Superseding agency | Ulster Defence Regiment |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

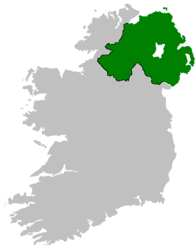

| National agency | Northern Ireland, UK |

| Operations jurisdiction | Northern Ireland, UK |

| |

| Map of Ulster Special Constabulary's jurisdiction | |

| Size | 13,843 km² |

| General nature | |

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men'") was a quasi-military[1] reserve police force in Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the partition of Ireland. It was an armed corps, organised partially on military lines and called out in times of emergency, such as war or insurgency.[2] It performed this role in 1920–22 during the Irish War of Independence and in the 1950s, during the IRA Border Campaign.

During its existence, 54 USC members were killed by the IRA, all but three in the years 1920 and 1921.[3]

The force was almost exclusively Ulster Protestant and as a result was viewed with great mistrust by Catholics. It carried out several revenge killings and reprisals against Catholic civilians in the 1920–22 conflict.[4][5] Unionists generally supported the USC as contributing to the defence of the Northern Ireland polity from subversion and outside aggression.[6]

The Special Constabulary was disbanded in May 1970, after the Hunt Report, which advised re-shaping Northern Ireland's security forces to attract more Catholic recruits[7] and disarming the police. Its functions and membership were largely taken over by the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) and the Royal Ulster Constabulary Reserve.[8]

Formation

The Ulster Special Constabulary was formed against the background of conflict over Irish independence and the partition of Ireland.

The 1919–1921 Irish War of Independence, saw the Irish Republican Army (IRA) launch a guerilla campaign in pursuit of Irish independence. Unionists in Ireland's northeast – who were against this campaign and against Irish independence – directed their energies into the partition of Ireland by the creation of Northern Ireland as an autonomous region within the remaining United Kingdom. This was enacted by the British Parliament in the Government of Ireland Act 1920.[9]

Two main factors were behind the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary. One was the desire of the unionists, led by Sir James Craig (then a junior minister in the British Government, and later the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland), that the apparatus of government and security should be placed in their hands long before Northern Ireland was formally established.[10]

A second reason was that violence in the north was increasing after the summer of 1920. The IRA began extending attacks to Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks and tax offices in the north and there had been serious rioting between Catholics and Protestants in Derry in May and June and in Belfast in July, which had left up to 40 people dead.[11]

With police and troops being drawn towards combating insurgency in the south and west, unionists wanted a force that would both take on the IRA and also help the under-strength RIC with normal police duties. Furthermore, many unionists did not trust the RIC, which being an all-Ireland force was mostly Catholic. A third aim was to control unionist paramilitary groups, who threatened, in the words of Craig, "a recourse to arms, which would precipitate civil war".[12][13]

Craig proposed to the British cabinet a new "volunteer constabulary" which "must be raised from the loyal population" and organised, "on military lines" and "armed for duty within the six county area only". He recommended that "the organisation of the Ulster Volunteers (the unionist militia formed in 1912) should be used for this purpose".[14] Wilfrid Spender, the former Ulster Volunteers quartermaster in 1913–14, and by now a decorated war hero, was appointed by Craig to form and run the USC.

The idea of a volunteer police force in the north appealed to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George for several practical reasons; it freed up the RIC and military for use elsewhere in Ireland, it was cheap, and it did not need new legislation. Special Constabulary Acts had been enacted in 1832 and 1914, meaning that the administration in Dublin Castle only had to use existing laws to create it. The formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary was therefore announced on 22 October 1920.[15][16]

On 1 November 1920, the scheme was officially announced by the British government.[17][18][19]

Composition

The composition of the USC was overwhelmingly Protestant and unionist, for a number of reasons. Several informal unionist "constabulary" groups had already been created, for example, in Belfast, Fermanagh and Antrim. The Ulster Unionist Labour Association had established an "unofficial special constabulary," with members drawn chiefly from the shipyards, tasked with ‘policing’ Protestant areas.[20] In April 1920, Captain Sir Basil Brooke, had set up "Fermanagh Vigilance", a vigilante group to provide defence against incursions by the IRA.[21] In Ballymacarrett, a Protestant rector named John Redmond had helped form a unit of ex-servicemen to keep the peace after the July riots.[22]

There was a willingness to arm or recognise existing Protestant militias. Wilfrid Spender, head of the Ulster Volunteer Force, encouraged his members to join.[23] There was an immediate and illicit supply of arms available; especially from the Ulster Volunteers.[24] Charles Wickham, Chief of Police for the north of Ireland, favoured incorporation of the Ulster Volunteers into "regular military units" instead of having to "face them down".[25] A number of these groups were absorbed into the new Ulster Special Constabulary.

Sinn Féin pointed out that the composition of the USC was overwhelmingly Protestant and unionist, and claiming the government was simply arming Protestants to attack Catholics.[26]

Efforts were made to attract more Catholics into the force, but it is claimed this was not encouraged by officialdom.[17][27] Catholic members were more easily targeted by the IRA for intimidation and assassination.[28] The government suggested that, with enough Catholic recruits, special constabulary patrols made up of Catholics only could be extended into Catholic areas.[26] However, the Nationalist Party and Ancient Order of Hibernians discouraged their members from joining.[citation needed] The IRA issued a statement which said that any Catholics who joined the specials would be treated as traitors by them and would be dealt with accordingly.[26]

Organisation

The USC was initially financed and equipped by the British government and placed under the control of the RIC. The USC consisted of 32,000 men divided into four sections, all of which were armed:

- A Specials – full-time and paid, worked alongside regular RIC men, but could not be posted outside their home areas (regular RIC officers could be posted anywhere in the country); usually served at static checkpoints (originally 5,500 members) [29]

- B Specials – part-time, usually on duty for one evening per week and serving under their own command structure, and unpaid, although they had a generous system of allowances (which were reduced following the reorganisation of the USC a few years later), served wherever the RIC served and manned Mobile Groups of platoon size;[30] (originally 19,000 members)[29]

- C Specials – unpaid, non-uniformed reservists, usually rather elderly and used for static guard duties near their homes (originally 7,500 members)[29]

- C1 Specials – non-active C class specials who could be called out in emergencies. The C1 category was formed in late 1921, incorporating the various local unionist militias such as the Ulster Volunteers into a new special class of the USC, thus placing them under the control and discipline of the Stormont Government.[31]

The units were organised on military lines up to company level. Platoons had two officers, a Head Constable, four sergeants and sixty special constables.[32]

The Belfast units were constructed differently from those in the counties. The districts were based on the existing RIC divisions. The constables drew pistols and truncheons before going on patrol and considerable efforts were made to use them only in Protestant areas. This did free regular policemen who were generally more acceptable to Ulster Catholics.[33]

By July 1921, more than 3,500 ‘A’ Specials had been enrolled, and almost 16,000 ‘B’ Specials. By 1922 recruiting had swelled the numbers to: 5,500 A Specials, 19,000 B Specials and 7,500 C1 Specials. Their duties would include combatting the urban guerrilla operations of the IRA, and the suppression of the local IRA in rural areas. In addition they were to prevent border incursion, smuggling of arms and escape of fugitives.[34]

Opposition

From the outset, the formation of the USC came in for widespread criticism, not only from nationalists, but also from elements of the British military and Administrative establishment in Ireland and in the British Press – who saw the USC as a potentially divisive and sectarian force.

Sir Nevil Macready General Officer Commanding-in-chief of the British army in Ireland withheld his approval for such a force, along with his supporters in the Irish administration but were overridden; Lloyd George approved of them from the beginning.[35] Macready and Henry Hughes Wilson argued that the concept of a special constabulary was a dangerous one.[36][37]

Wilson warned that the formation of a partisan unionist constabulary, "would mean; taking sides, civil war and savage reprisals."[38][39] John Anderson, the Under Secretary for Ireland (head of the British Administration in Dublin) shared his fears, "you cannot, in the middle of a faction fight, recognise one of the contending parties and expect it to deal with disorder in the spirit of impartiality and fairness essential in those who have to carry out the order of the Government."[40]

The Nationalist Press was even more scathing.

The Fermanagh Herald noted the opposition of Nationalists:[41]

These “Special Constables” will be nothing more and nothing less than the dregs of the Orange lodges, armed and equipped to overawe Nationalists and Catholics, and with a special object and special facilities and special inclination to invent ‘crimes’ against Nationalists and Catholics... they are the very classes whom an upright Government would try to keep powerless...

Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Hezlet in the official History of the Ulster Special Constabulary,[42] put forward the view:

"Sinn Fein regarded the Specials as an excuse for arming the Orangemen and an act even more atrocious than the creation of the 'Black and Tans'! Their fury was natural as they saw that the Specials might well mean that they would be unable to intimidate and subdue the North by Force. Their skilful propaganda set about blackening the image of Special Constables, trying to identify them with the worst elements of the Protestant mobs in Belfast. They sought to magnify and distort every incident and to stir up hatred of the force even before it started to function."[43]

Training, uniform, weaponry and equipment

The standard of training was varied. In Belfast, the Specials were trained in much the same way as the regular police whereas in rural areas the USC was focused on counter-guerilla operations. 'A Specials' were initially given six weeks training at Newtownards Camp in police duties, the use of arms, drill and discipline.[citation needed]

Uniforms were not available at the outset so the men of the B Specials went on duty in their civilian clothes wearing an armband to signify they were Specials. Uniforms did not become available until 1922. Uniforms took the same pattern as RIC/RUC dress with high collared tunics. Badges of rank were displayed on the right forearm of the jacket.[44]

The Special Constables were armed with a Webley .38 revolver and also Lee-Enfield rifles and bayonets.[45] By the 1960s Sten and Sterling submachine guns were also used. In most cases these weapons were retained at home by the constables along with a quantity of ammunition. One of the reasons for this was to enable rapid call out of platoons, via a runner from the local Police station, without the need to issue arms from a central armoury.

"A Special" Platoons were fully mobile using a Ford car for the officer in charge, two armoured cars and four Crossley Tenders (one for each of the sections).

B Specials generally deployed on foot but could be supplied with vehicles from the police pool.

Conflict 1920–1922

Deployment of the USC in 1920–22 provided the Northern Ireland government with its own territorial militia, to repel IRA attacks. The use of Specials to reinforce the RIC also allowed for the re-opening of over 20 barracks in rural areas which had previously been abandoned because of IRA attacks.[46] The cost of maintaining the USC in 1921–22 was £1,500,000.

However, their conduct towards the Catholic population was criticised on a number of occasions. In February 1921, for example it was alleged that Specials burned down Catholic houses in the County Fermanagh village of Roslea. Following the death of a Special Constable near Newry on 8 June 1921, it was alleged that Specials and an armed mob were involved in the burning of 161 Catholic homes and the death of 10 Catholics. An inquest advised that the Special Constabulary, "should not be allowed into any locality occupied by people of an opposite denomination."[47] Although the government suggested the recruitment of more Catholics to form "Catholic only" patrols to cover Catholic areas.[26]

After the Truce between the IRA and the British on 11 July 1921, the USC was demobilised by the British and the IRA was given official recognition while peace talks were ongoing.[48] However, the force was remobilised in November 1921, after security powers were transferred from London to the Northern Ireland Government.

Michael Collins planned a clandestine guerilla campaign against the Northern state using the IRA. In early 1922, he sent IRA units to the border areas and arms to northern units. On 6 December the Northern authorities ordered an end to the Truce with the IRA.[49]

The Special Constabulary was, as well as an auxiliary to the police, effectively an army under the control of the Northern Ireland administration. By incorporating the former Ulster Volunteers into the USC as the C1 Specials, the Belfast government had created a mobile reserve of at least two brigades of experienced troops in addition to the A and B Classes who, between them, made up at least another operational infantry brigade, which could be used in the event of further hostilities.[50] Such hostilities did indeed break out in early 1922.

"Border war" 1922

The USC's most intense period of deployment was in the first half of 1922, when conditions of a low-intensity war existed along the border between The Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty had agreed the partition of Ireland, between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The IRA, though now split over the Treaty, continued offensive operations in Northern Ireland, with the co-operation of Michael Collins, leader of the Free State, and Liam Lynch, leader of the Anti-Treaty IRA faction. This was despite the Craig-Collins Agreement which was signed by the leaders of Northern Ireland and the Free State on 30 March, and envisaged the end of IRA activity and a reduced role for the USC.[51]

The renewed IRA campaign involved attacking barracks, burning commercial buildings and making a large-scale incursion into Northern territory occupying Belleek and Pettigo in May–June, which was repulsed after heavy fighting, including British use of artillery on 8 June.[52][53][54]

The British Army was only used in the Pettigo and Belleek actions. Therefore the main job of counter-insurgency in this, undeclared border war fell to the Special Constabulary while the RIC/RUC dealt with civil disturbances. Forty nine Special Constables were killed during the period of the "Border War" – out of a total of eighty one British forces killed in Northern Ireland.[55][56] Their biggest single loss of life came at Clones in February 1922, when a patrol, changing trains in Southern territory, refused to surrender to the local IRA garrison and took four dead and eight wounded in a firefight.[57]

In addition to action against the IRA, the USC may have been involved in a number of attacks on Catholic civilians in reprisal for IRA actions.[28] For example, in Belfast, the McMahon Murders of March 1922, in which six Catholics were killed,[58][59] and the Arnon Street killings a week later which killed another 6.[60] On 2 May 1922 in revenge for the IRA killing of 6 policemen in counties Londonderry and Tyrone, Special Constables killed nine Catholic civilians in the area.[61]

The conflict never formally ended but petered out in June 1922, with the outbreak of the Irish Civil War in the South and the wholesale arrest and internment of IRA activists in the North.[62] Collins continued to arrange the supply of arms covertly to the Northern IRA until shortly before his death in August 1922.[63]

Assessments of the USC's role in this conflict vary according to partisan allegiance. Unionists have written that the Special Constabulary, "saved Northern Ireland from anarchy" and "subdued the IRA". While nationalist authors have judged that their treatment of the Catholic community, including, "widespread harassment and a significant number of reprisal killings" permanently alienated nationalists from the USC itself and more broadly, from the Northern Irish state.[64]

1920s to 1940s

After the end of the 1920–22 conflict, The Special Constabulary was re-organised. The regular Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) took over normal policing duties.[65]

The 'A' and 'C' categories of the USC were dispensed with, leaving only the B-Specials, who functioned as a permanent reserve force, and armed and uniformed in the same manner as the RUC.[65]

There were occasions when the Special Constabulary needed to turn out for duty. One such example is the 12 July period in Belfast in 1931 when sectarian rioting broke out. The B Specials were tasked to relieve the RUC from normal duties to allow them and the British Army to deal with the disturbances.[55]

During the Second World War, the USC was mobilised to serve in Britain's Home Guard, which unusually, was put under the command of the police rather than the British Army.[66]

1950s – IRA Border Campaign

Between 1956 and 1962, the Special Constabulary was again mobilised to combat a guerilla campaign launched by the IRA.

Damage to property during this period was £l million and the overall cost of the campaign was £10 million to the UK exchequer.[67] Tim Pat Coogan, the Irish historian, said at the time of the USC, "The B Specials were the rock on which any mass movement by the IRA in the North has inevitably floundered."[68]

Six RUC men and eleven Republicans but no Special Constables were killed in this campaign.

The IRA called off their campaign in February 1962.

1969 deployment

The USC were deployed in 1969 to support the RUC in the 1969 Northern Ireland Riots. The B Specials' role in these events led to its disbandment the following year.

Northern Ireland had been destabilised by disturbances arising out of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association's agitation for equal rights for Catholics.

The USC were mobilised when the regular RUC were overstretched by riots in Derry—known as the Battle of the Bogside. The NICRA called for protests elsewhere to support those in Derry, leading to the violence spreading throughout Northern Ireland – especially in Belfast.

The USC were largely held in reserve in July and only hesitantly committed in August.[69] The General Officer Commanding of the British Army in Northern Ireland refused to allow the Army to become involved until the Belfast administration has used "all the forces at its disposal". This meant that the B Specials had to be deployed, although they were not trained or equipped to undertake this type of public disorder.[70]

The two main centres of disturbance were in Belfast and Derry. A total of 300 Special Constables were also mobilised into the RUC during the disturbances.

Some Constables were used to restrain a Protestant crowd in Derry, but others in this area joined in an exchange of petrol bombs and missiles with a Catholic crowd while another group led an attack on the Rossville Street area of the Catholic Bogside on 12 August.[71][72]

In Belfast the USC were successful in restoring order in the predominantly Protestant Shankill area,where they performed their patrol duties unarmed. On one occasion, the Comber Platoon was petrol-bombed by a hostile Protestant crowd at Inglis's bakery as it tried to protect Catholics who were going to work. They also successfully protected Catholic owned public houses in the area, many of which were looted after they were withdrawn.[73] However, on 14 August they did not hold back Protestants who attacked Catholic streets as Dover and Percy streets in the Falls/Divis district and "fought back" a Catholic mob moving up from Dover Street and Percy street.[74]

USC Shootings

The USC's most controversial conduct in the 1969 riots came in provincial towns, where the Special Constabulary formed the main response to the rioting. The Specials, who were armed and not trained for riot duty, used deadly force on a number of occasions.[75]

The USC shot and wounded a number of people Dungiven, Coalisland and in Dungannon they killed one and wounded two. In the following Scarman tribunal the findings said "...the Tribunal has been at a loss to find any explanation for the shooting, which it is satisfied was a reckless and irresponsible thing to do."[76]

When Jack Lynch the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland moved Irish Army troops up to the border, in response to the rioting, platoons of Specials were deployed to guard border police stations.[70]

Arising out the disturbances, the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced that the B Specials would be "phased out of their current role". The British Government commissioned three reports into the policing response to the 1969 riots. These ultimately led to the disbanding of the Ulster Special Constabulary.

The Cameron Report

Sir John Cameron was requested to submit a report on the disturbances in Northern Ireland.[77]

He found some evidence of cross membership of the USC in Loyalist paramilitary organisations. He reported that in Major Ronald Bunting's Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV) there was definite evidence of dual membership by Special Constables. Which "we consider highly undesirable and not in the public interest"[78] He also remarked that although "recruitment is open to both Protestant and Roman Catholic: in practice we are in no doubt that it is almost if not wholly impossible for a Roman Catholic recruit to be accepted."[79]

Cameron recommended that the purposes of the USC as reserve civilian police force, as well as a counter-insurgency reserve, be properly made known in recruitment and training so that it would be more attractive to Catholics.[80]

The Scarman Report

The Hon Justice Scarman, in his report on the rioting, was critical of the RUC's senior officers and of the way the B Specials were deployed into areas of civil disturbance which they had no training to deal with, which in some occasions led to a worsening of the situation. He also pointed out that the B Specials were the only reserve available to the RUC and that he could see no other way of quickly reinforcing the under strength RUC in the circumstances. He did give praise to the Specials where he felt it was due.[29]

Lord Justice Scarman concluded in his report on the Civil Disturbance in the Province in 1969 that: Undoubtedly mistakes were made and certain individual officers acted wrongly on occasions. But the general case of a partisan force co-operating with Protestant mobs to attack Catholic people is devoid of substance, and we reject it utterly.[81]

Scarman went on to criticise the Command and Control of the RUC for deploying armed Special Constables in areas where their very presence would "heighten tension" as he was in no doubt that they were "Totally distrusted by the Catholics, who saw them as the strong arm of the Protestant ascendancy".[81]

Scarman concluded that it would have been very difficult for Catholics to gain membership in 1969, even if they had applied to join.

The Hunt Report

The abolition of the B Specials was a central demand of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s.

On 30 April 1970, the USC was finally stood down, as a result of the Hunt Committee Report. Hunt concluded that the perceived bias of the Special Constabulary, whether true or not, had to be addressed. One of his other major concerns was the use of the police force for carrying out military style operations. His recommendations included:[7]

(47) A locally recruited part-time force, under the control of the G.O.C., Northern Ireland, should be raised as soon as possible for such duties as may be laid upon it. The force, together with the police volunteer reserve, should replace the Ulster Special Constabulary (paragraph 171).

Disbandment

The Ulster Special Constabulary was disbanded in May 1970.

It has been argued that their failure to deal with the 1969 disturbances were due to a failure on behalf of the Northern Ireland government to modernise their equipment, weaponry, training and approach to the job.[82]

On the disbandment of the USC, many of its members joined the newly established Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), the part-time security force which replaced the B Specials. Unlike the Special Constabulary, the UDR was placed under military control. Other B Specials joined the new Part Time Reserve of the RUC. The USC continued to do duties for a month after the formation of the UDR and RUC Reserve to give both of the new forces time to consolidate.

In the final handover to the Ulster Defence Regiment, the B Specials had to surrender their weapons and uniforms.[83]

Despite the government's concerns about the handover of weapons and equipment, every single uniform and every single weapon was handed in.[84]

The last night of duties for most B Men was 31 March 1970. On 1 April 1970 the Ulster Defence Regiment began duties.[85]

Continuing influence

Since disbandment the USC has assumed a place of "almost mythic proportions" within unionist folklore, whereas in the Nationalist community they are still reviled as the Protestant only, armed wing of the unionist government "associated with the worst examples of unfair treatment of Catholics in Northern Ireland by the police force".[86] An Orange lodge was formed to commemorate the disbandment of the force called "Ulster Special Constabulary LOL No 1970".[86] An Ulster Special Constabulary Association was also set up soon after the disbandment.

Notable members

See also

- Auxiliary Constable

- Auxiliary police

- Alexander Robinson

- Special constable

- Special constabulary

- Special police

Bibliography

- The B-Specials: A History of the Ulster Special Constabulary (1972) Sir Arthur Hezlet ISBN 0-85468-272-4

- Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920–27, Michael Farrell, Pluto Press (London/Sydney 1983), ISBN 0-86104-705-2

- The Thin Green Line The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books – ISBN 1-84415-058-5

- The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Liz Curtis, Beyond the Pale Publications 1995, Belfast, ISBN 978-0-9514229-6-0

- Peace in Ireland: The War of Ideas, Richard Bourke, Pimlico 2003, ISBN 1-84413-316-8

- A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4

- Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Pluto Press (1992), ISBN 0-902818-87-2, p.

- Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control, Dominic Bryan, Pluto Press (2000), ISBN 0-7453-1413-9

- The Crowned Harp: Policing Northern Ireland, Graham Ellison, Jim Smyth, Pluto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7453-1393-0

- Red Hand: The Ulster Colony, Constantine Fitzgibbon, Michael Joseph Ltd (1971) ISBN 978-0-7181-0881-6

- Belfast’s Unholy War, Alan F. Parkinson, Four Courts Press 2004, ISBN 1-85182-792-7

- The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition, Robert Lynch, Irish Academic Press, Dublin 2006, ISBN 0-7165-3377-4.

- The Irish War of Independence, Michael Hopkinson, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 2004. ISBN 0-7171-3741-4

- Green against Green, the Irish Civil War, Michael, Hopkinson, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 2004, : ISBN 978-0-7171-1202-9

- The police forces of Northern Ireland – history, perception and problems, Johannes Steffens, ISBN 978-3-638-75341-8

- The State:Historical and Political Dimensions, Richard English: Charles Townshend, 1998, Routledge, ISBN 0415154774

- The Northern Ireland Question: Myth and Reality, Patrick J. Roche: Brian Barton, Wordzworth, 2013, ISBN 1783240008

- Potter, John Furniss. A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4

- David R Orr (2013), "RUC Spearhead: The RUC Reserve Force 1950-1970" Redcoat Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9538367-4-1.

External links

- RUC police federation B-Specials page (note: despite the domain name, this is not the official website of the RUC or its successor, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI))

- USC Roll of Honour

- Ulster Special Constabulary Roll of Honour

References

- ^ English:Townshend p96

- ^ Alan F. Parkinson, Belfast's Holy War, p83-84

- ^ http://www.policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/n_ireland/usc/usc_roll.htm

- ^ Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p263

- ^ http://www.historyireland.com/revolutionary-period-1912-23/belfasts-unholy-war/

- ^ Thomas Hennessey (1997) A History of Northern Ireland 1920 – 1996, p.15. Gill & Macmillan:Dublin. ISBN 0-7171-2400-2

- ^ a b CAIN: HMSO: Hunt Report, 1969

- ^ Sydney Elliott, William D. Flackes, Conflict in Northern Ireland: an encyclopaedia

- ^ Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920–27, Michael Farrell, Pluto Press (London/Sydney 1983), ISBN 0-86104-705-2, pp. 7–8

- ^ Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p. 155

- ^ Hopkinson, pp. 155–156

- ^ Arming the Protestants: The Formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary and the Royal Ulster Constabulary 1920–27, Michael Farrell, Pluto Press (London/Sydney 1983), ISBN 0-86104-705-2, p. 13

- ^ Alan F. Parkinson, Belfast's Unholy War, p. 84

- ^ Parkisnon p 84

- ^ Parkinson p84.

- ^ Hezlet, p. 19

- ^ a b Liz Curtis, The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Beyond the Pale Publications 1995, Belfast, ISBN 0-9514229-6-0, pp. 346–7

- ^ Richard Bourke, Peace in Ireland: The War of Ideas, Pimlico 2003, ISBN 1-84413-316-8, p. 48

- ^ The Crowned Harp: Policing Northern Ireland, Graham Ellison, Jim Smyth, Pluto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7453-1393-0, pp. 25–6

- ^ Paul Bew, Peter Gibbon and Henry Patterson, Northern Ireland: 1921 / 2001 Political Forces and Social Classes, Serif (London 2002), ISBN 1-897959-38-9, pp.18–19.

- ^ Hezlet, pp10–11

- ^ Parkinson, p46-47

- ^ parkinson p 86

- ^ Hezlet, page 10

- ^ Parkinson, p88

- ^ a b c d Doherty p14

- ^ Northern Ireland: Crisis and Conflict, John Magee, Routledge, 1974, ISBN 0-7100-7946-X, p. 70

- ^ a b Doherty p18

- ^ a b c d The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books – ISBN 1-84415-058-5

- ^ PSNI [dead link]

- ^ Hezlet pp. 50–52

- ^ Hezlet, p. 27

- ^ Hezlet, p. 29

- ^ Hezlet p. 83

- ^ Bew, p28

- ^ Wilson wrote, "To arm those “Black men” in the north without putting them under discipline is to invite trouble." Paul Bew, Peter Gibbon and Henry Patterson, Northern Ireland: 1921 / 2001 Political Forces and Social Classes, Serif (London 2002), ISBN 1-897959-38-9, p. 28

- ^ Annals of an Active Life, G.F.N. Macready, London 1924, Vol 2, p. 488. cited

- ^ Bew p28"

- ^ Wilson papers, 26 July 1920, in Gilbert, Churchill, Companion Vol. 4, part 2, p. 1150.

- ^ Parkinson p. 87

- ^ Fermanagh Herald, 27 November 1920

- ^ "Vice-Admiral Sir Arthur Hezlet". The Daily Telegraph. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ Hezlet, pp. 22–24

- ^ [1][dead link] [dead link]

- ^ Parkins, p85

- ^ Hezlet, p. 32

- ^ Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Pluto Press (1992), ISBN 0-902818-87-2, p.40-41

- ^ Lynch, Northern Divisions, p80.

- ^ Lynch p 88-89

- ^ Hezlet p. 53, 82

- ^ Craig-Collins Agreement text; downloaded 7 November 2010

- ^ A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4 p. 4

- ^ Michael Hopkinson, Green against Green, p82-87

- ^ "New York Times", 9 June 1922. Archive Retrieved 22 November 2011

- ^ a b A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4 p5

- ^ Lynch, p67, another 530 civilians and 35 IRA men were killed in the Northern conflict of 1920–1922, Lynch p227

- ^ Lynch, p141-144

- ^ The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books – ISBN 1-84415-058-5 p18

- ^ Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Pluto Press (1992), ISBN 0-902818-87-2, p.51

- ^ Robert Lynch, The Northern IRA and Early Years of Partition p 122-123

- ^ Lynch p141-143

- ^ Parkinson, Unholy War, p.316

- ^ Sunday Independent, 22 August 2010

- ^ Parkinson p94-95

- ^ a b Johannes Steffens, Police Forces of Northern Ireland, p4

- ^ Steffens p 5

- ^ Royal Ulster Constabulary

- ^ The I.R.A. (Fully revised and updated, paperback 2000), Tim Pat Coogan, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-653155-5, p. 37

- ^ Scarman 3.14

- ^ a b A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4 p. 10

- ^ Scarman 3.18

- ^ Scarman 3.24

- ^ Scarman 3.15–3.16

- ^ Scarman Report 3.16–3.23

- ^ Scarman Report 3.20

- ^ "Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 – Report of Tribunal of Inquiry". CAIN. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ CAIN: HMSO: Cameron Report - Disturbances in Northern Ireland (1969), Chapters 1-9

- ^ item 220

- ^ item 183

- ^ item 184

- ^ a b CAIN: Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 - Report of Tribunal of Inquiry

- ^ Potter p17

- ^ A Testimony to Courage – the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 – 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0-85052-819-4 p. 16

- ^ Potter p16

- ^ Potter p34

- ^ a b Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control by Dominic Bryan, Pluto Press (2000) ISBN 0-7453-1413-9 p. 94

- ^ Potter p361