User:Enryonokatamarikun/sandbox

Délits and punishments

[edit]The Code Noir permits corporal punishment for slaves and provides for disfigurement by branding with an iron, as well as for the death penalty (articles 33-36 and 38). Runaway slaves who have disappeared for a month will have their ears cut off and will be branded with the fleur de lys. In the case of recidivism, the slave’s hamstring will be cut. Should there be a third attempt, the slave will be put to death. It is important to note that these kinds of punishments (branding by iron, mutilation, etc.) also existed in metropolitan France’s penological practice at the time.[1]

Punishments were a matter of public or royal law, where the disciplinary power over slaves could be considered more severe than that for domestic servants yet less severe than that for soldiers. Masters could only chain and whip slaves “when they believe that their slaves deserved it” and cannot, at will, torture their slaves, or put them to death.

The death penalty is reserved for those slaves who have struck their master, his wife, or his children (article 33) as well as for thieves of horses or cows (article 35) (larceny by domestic servants was also punishable by death in France).[2] The third attempt to escape (article 38) and the congregation of recidivist slaves belonging to different masters (article 16) were also offenses punishable by death.

Although forbidden for the master to mistreat, injure, or kill his slaves, he nevertheless possessed disciplinary power (article 42) according to the Code. “Masters shall only, when they believe that their slaves so deserve, be able to chain them and have them beaten with rods or straps”, similar to pupils, soldiers, or sailors.

Article 43 addresses itself to judges: “to punish murder while taking into account the atrocity of the circumstances; in the case of absolution, our officers will…” The most serious punishments, such as the cutting of the ears or of the hamstring, branding, and death are prescribed by a criminal court in the case of conviction and imposed by a magistrate rather than by the slave’s master. However, in reality, the conviction of masters for the murder or torture of slaves was very rare.

Seizure and slaves as chattels

[edit]With respect to the inheritance of property, estate, and seizures, slaves were considered to be personal property (article 44), that is, considered separate from the estate on which they live (which was not the case with serfs). Despite this, slaves could not be seized by a creditor as property independent of the estate, with the exception of compensating the seller of the slaves (article 47).

According to the Code, slaves can be bought, sold, and given like any chattels. Slaves were provided no name or civil registration, rather, starting in 1839, they were given a serial number. Following the 1848 abolition of slavery under the French Second Republic, a name was assigned to each former slave.[3] Slaves could testify, have a proper burial (for those baptized), lodge complaint, and, with the master’s permission, have savings, marry, etc. Nevertheless, their legal capacity was still more restrictive than that of minors or domestic servants (articles 30 and 31). Slaves had no right to personal possessions and could not bequeath anything to their families. Upon the death of the slave, all remained property of the master (article 28).

Married slaves and their prepubescent children could not be separated through seizure or sale (article 47).

Emancipation / manumission

[edit]Slaves could be manumitted by their owner (article 55), in which case no naturalization records were required for French citizenship, even if the individual was born abroad (article 57). However, starting in the 18th century, manumission required authorization as well as the payment of an administrative tax. The tax was first instituted by local officials, but later affirmed by the edict of October 24th, 1713 and the royal ordinance of May 22, 1775.[4] Manumission was considered de jure if a slave was designated the sole legatee of the master (article 56).

Adoptive Territories

[edit]

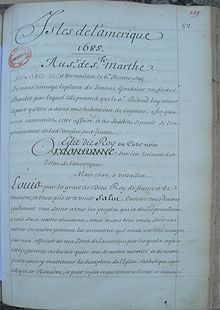

Based on the fundamental law that any man who sets foot on French soil is free, various parliaments refused to pass the original Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique which was ultimately instituted only in the colonies for which the edict was written: the Sovereign Council of Martinique on the 6th of August, 1685, Guadeloupe on December 10th of the same year, and in Petit-Goâve before the Council of the French colony of Saint-Domingue on May 6th, 1687.[5] Finally, the Code was passed before the councils of Cayenne and Guiana on May 5th, 1704.[5] While the Code Noir was also applied in the colony of Saint Christopher, the date of its institution is unknown. The edicts of December 1723 and March 1724 were instituted in the islands of Réunion (Île Bourbon) and Mauritius (Île de France) as well as in the colony and province of Louisiana, in 1724.[6]

The Code Noir was not intended for northern New France (present day Canada) where the general principle of French law that Indigenous peoples of lands conquered or surrendered to the Crown be considered free royal subjects (régnicoles) upon their baptism. Various local indigenous customs were collected to create the Custom of Paris. However, on April 13th, 1709, an ordinance created by Acadian colonial intendant Jacques Raudot imposed regulations on slavery thereby recognizing, de facto, its existence in the territory. The ordinance elaborated little on the legal status of slaves, but generally characterized slavery as “a kind of convention” that is “very useful for this colony”, proclaiming that “all Panis and Negroes who have been purchased or who will be purchased at some time, will belong to those who have purchased them as their full property and be known as their slaves”.[7][8][9]

After the Revolution

[edit]The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 articulated the principle of equal rights from birth for all, but under the lobbying influence of the Massiac Club of plantation and slave owners, the National Constituent Assembly and the Legislative Assembly decided that this equality applied only to the inhabitants of metropolitan France, where there were no slaves and where serfdom had been abolished for centuries. The American territories were likewise excluded.

After Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti) abolished slavery locally in 1793, the French National Convention did the same on February 4th, 1794 for all French colonies. This would only be effective, however, in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Guiana, because Martinique was, at this time, a British colony and Mascarene colonists forcibly opposed the institution of the 1794 decree when it finally arrived to the isle in 1796.

Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated slavery on May 20th, 1802 in Martinique and the Mascarenes, as the islands had been returned by the British after the Treaty of Amiens. Soon after, he reestablished slavery in Guadeloupe (on July 16th, 1802) and Guiana (in December of 1802). Slavery was not reestablished in Saint-Domingue due to the resistance of the Haitians against the expeditionary corps sent by Bonaparte. A resistance which eventually resulted in the independence of the colony and the formation of the Republic of Haiti on January 1, 1804.

The Code Noir coexisted for forty-three years with the Napoleonic code despite the contradictory nature of the two texts, but this arrangement became increasingly difficult due to the French Court of Cassation rulings on local jurisdictions’ decisions following the 1827 and 1828 ordinances on civil procedures. According to historian Frédéric Charlin, in metropolitan France, “the two decades of the July Monarchy were characterized by a political trend to endow the slave with a certain level of humanity… [and to] encourage a slow assimilation of the slave into other workforces of French society through moral and family values.”[10] The jurisprudence of the Court of Cassation under the July Monarchy was marked by a gradual recognition of a legal personhood for slaves. Accordingly, the 1820s saw a general abolitionist trend, but one that was mainly preoccupied with a gradual emancipation that paralleled improved conditions for slaves.[10]

The revolution of February 1848 and the creation of the Second Republic brought prominent abolitionists such as Cremieux, Lamartine, and Ledru-Rollin to power. One of the first acts of the Provisional Government of 1848 was to establish a commission to “prepare for the act of emancipation of slaves of the colonies of the Republic.” The commission was completed and presented to the government in less than two months and subsequently instituted on April 27th, 1848.

The enslavement of black people in French colonies was definitively abolished on March 4th and April 27th of 1848. Due in large part to the actions of Victor Schoelcher,[11] the slave trade had already been abolished in 1815, following the Congress of Vienna.

Article 8 of the decree of April 27th, 1848 extended the Second Republic’s ban on slavery to all French citizens residing in foreign countries where the possession of slaves was legal, while according them a grace period of three years to conform to the new law. In 1848, there numbered around 20,000 French nationals in Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Louisiana was, by far, the region home to the most slave owning French, who, despite the 1803 sale of the territory to the U.S. government, retained citizenship. Article 8 forbade all French citizens “to buy, sell slaves, or to participate, whether directly or indirectly, in any traffic or exploitation of this nature.” The application of this law was not accomplished without difficulty in these regions, with Louisiana being particularly problematic.[12]

The development of slavery in the French Antilles

[edit]The origins of enslaved populations

[edit]

The edict of 1685 bridged a legal void, because, while slavery existed in the French Caribbean since at least 1625, it was nonexistent in metropolitan France. The first official French establishment in the Antilles was the Company of Saint Christopher and neighboring islands (Compagnie de Saint-Christophe et îles adjacentes) which was founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1626. In 1635, 500-600 slaves were acquired, through what was essentially a seizure of a slave shipment from the Spanish. Later, the number was increased by slaves brought from Guinea aboard Dutch or French ships. With the island becoming overpopulated, there were efforts to colonize Guadeloupe with the aid of French recruits in 1635, as well as Martinique with the aid of 100 “old residents” of Saint Christopher in the same year.

In Guadeloupe, the influx of slaves started in 1641 with the Company of Saint Christopher (by this date renamed Company of the American Isles and owner of multiple islands) importing 60 enslaved people. Then, in 1650, the company imported 100 more.[13] Starting in 1653-1654 the population greatly increased with the arrival of 50 Dutch nationals to the French isles, who had been run out of Brazil, taking with them 1200 black and métis slaves.[14] Subsequently, 300 people composed mainly of a few Flemish families and a great many slaves, settled in Martinique.[15] Many of these immigrants were Sephardic Jewish planters from Bahia, Dutch Penambuco, and Suriname, who brought sugarcane infrastructure to French Martinique and English Barbados.[16] Although colonial authorities were hesitant to allow entry to the Jewish families, the French decided that their capital and proficiency in cane cultivation would benefit the colony. Some historians suggest that these Jewish planters, such as Benjamin da Costa d'Andrade, were responsible for introducing commercial sugar production to the French Antilles.[17] After the Da Costa family founded the first synagogue of Martinique in 1676, the visible Jewish presence in Martinique and Saint-Domingue led Jesuit missionaries to petition for the expulsion of Jews and other non-Catholics to both local and metropolitan authorities.[17][18] This precipitated an edict expelling Jews from the colonies in 1683, which would be incorporated into the Code Noir.[18] The Jewish population of Martinique was likely the specific target of the antisemitic clause (article 1) of the original 1685 Code. These settlers’ arrival in the 1650s marked the second stage of colonization. Until then, tobacco and indigo cultivation had been the mainstay of colonial efforts and had required more laborers than slaves, but this trend was reversed around 1660 with the development of cane cultivation and large plantation estates.[19]

Thereafter, the French State made the facilitation of the slave trade a matter of primary concern and worked to undercut foreign competition, particularly Dutch slavers. It is undeniable that the French East India Company, as the owner of slaveholding isles, took part in the slave trade, even though commercial slavery was not explicitly stated in the 1664 edict that chartered the company. The word “trade” was generally defined as any form of trade or commerce and did not exclude commerce in slaves as it might today. Despite the creation of various incentive plans in 1670, 1671, and 1672, the company went bankrupt in 1674 and the islands in its possession became crown lands (domaine royal). The monopoly on the Caribbean trade was given to the Senegal Company (Première compagnie d'Afrique ou du Sénégal) in 1679. To amend what was seen as an insufficient supply, Louis XIV created the Company of Guinea (Compagnie de Guinée—not to be confused with the 17th century English colonial enterprise Guinea Company) to provide a yearly supplement of 1000 black slaves to the French isles. To solve the “negro shortage”, in 1686, the King personally chartered a slave ship for operation in Cape Verde.

At the time of the first official census of Martinique, taken in 1660, there were 5259 inhabitants, 2753 of which were white and already 2644 were black slaves. There were only 17 Indigenous Caribbeans and 25 mulattoes. Twenty years later, in 1682, the number of inhabitants had tripled to 14,190 with a white population that had barely doubled, but with a slave population that had grown to 9634, and with the Indigenous population at a mere 61, slaves made up 68% of the total population.[20]

In all of the colonies, there was a great disparity between the number of men and women which led to men having children with Indigenous women, who were free persons, or with slaves. With white women being rare and black women seeking to improve their circumstances, by 1680 the census showed 314 métis people in Martinique (twelve times the count in 1660), 170 in Guadeloupe, and 350 in Barbados where the slave population was eight times that of Guadeloupe but where miscegenation (métissage) was illegalized after the rise of sugarcane cultivation.

To mitigate the deficit of women in the Antilles, Versailles enacted a similar measure to the King’s Daughters of New France and sent 250 girls to Martinique and 165 to Saint-Domingue.[21] Compared to its English counterpart, which sent condemned criminals and exiled populations, the French migration was voluntary. Creolization was unavoidable due to basic endogamous tendencies, with colored women being preferred as many colonists considered the new arrivals to be foreigners.[22]

The authorities were not concerned with miscegenation per se, but rather the resulting manumission of mulatto children.[23] For this reason, the Code inverted basic patrimonial French custom in maintaining that even if the father is free, the children of an enslaved woman shall be slaves unless they are rendered legitimate through the marriage of the parents, which was a rare occurrence. In subsequent regulation, marriage between free and slave populations would be further limited.

The Code Noir also more sharply defined the status of métis people. In 1689, four years after its promulgation, around one hundred mulattoes left the French Antilles for New-France, where all men were considered free.

The Development of the Code Noir

[edit]The goals of the Code Noir

[edit]In a controversial 1987 analysis of the Code Noir,[24] legal philosopher Louis Sala-Molins argued that the Code served two purposes: the first, being the affirmation of “the sovereignty of the State in its remote territories” and the second, being the promotion of sugarcane cultivation. Stating that “in this sense, the Code Noir foresaw a possible sugar hegemony for France in Europe. To achieve this goal, it was first necessary to condition the tool of the slave”.[25]

With regards to religion, the ordinance of 1685 excluded all who were not Catholic and prescribed baptism, religious instruction, and the same practices and sacraments for slaves as it did for free persons. In this way, slaves had the right to rest on Sundays and holidays, to formally marry through the church, and to be buried in proper cemeteries.

The Code thus gave a guarantee of morality to the Catholic nobility that arrived in Martinique between 1673 and 1685.[26] Of these, were Knight Charles François d'Angennes, the marquis of Maintenon and his nephew Jean-Jacques Mithon de Senneville, the colonial intendant Jean-Baptiste Patoulet, Charles de Courbon, the count of Blénac, and the militia captain Nicolas de Gabaret.

Juridical origins and similar legislation

[edit]English colonies

[edit]In the English colonies, the Barbados Lifetime Slavery Decree of 1636 was instituted by governor Henry Hawley on his return to England after having entrusted Barbados to his deputy governor Richard Peers.[27] In 1661, the Barbados Slave Code reiterated this 1636 decree and the 1662 Virginia slave law passed by governor William Berkeley under the reign of Charles II used similar jurisprudence. The 1661 law held that a slave could only produce enslaved children[28] and that mistreatment of a slave could be justified in certain cases.[29] The law also incorporated the Elizabeth Key case (a mulatto slave, daughter of a white plantation owner, who converted to Christianity and successfully sued for her freedom) which was contested by the white aristocracy who held that paternity and conversion were unable to confer freedom.

French colonies

[edit]Contrary to the thinking of legal theorists such as Leonard Oppenheim,[30] Alan Watson,[31] and Hans W. Baade,[32] it was not slave legislation from Roman law that served as inspiration for the Code Noir, but rather a collection and codification of the local customs, decisions, and regulations used in the Antilles. According to legal scholar Vernon Palmer, who has described the lengthy 4-year decision-making process that led to the original 1685 edict, the project consisted of 52 articles for the first draft and preliminary report, as well as the instructions of the King.[33]

In 1681, the King decided to create a statute for the black population of the French Caribbean and delegated its writing to Colbert, who, in turn, requested memoranda from the colonial intendant of Martinique, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet and later from his replacement, Michel Bégon, as well as the governor general of the Caribbean, Charles de Courbon, comte de Blenac (1622-1696). The Mémoire (memorandum) of April 30th, 1681 from the King to the intendant (who was probably Colbert), expressed the utility of making an ordinance specific to the Antilles.

The study, which incorporated local legal customs, decisions, and jurisprudence of the Sovereign Council, as well as a number of rulings by the King’s Council, was challenged by the members of the Sovereign Council. When negotiations settled, the draft was sent to the chancellery which retained what was essential and only reinforced or streamlined the articles such that they were compatible with preexisting laws and institutions.

At the time, there were two common law statutes in effect in Martinique: that pertaining to French nationals, which was the Custom of Paris as well as laws for foreigners, which did not include rules particular to soldiers, nobles, or clergy. These statutes were included in the Edict of May 1664 which established the French West India Company. The American Isles were enfeoffed or conceded to the Company, whose formation had replaced the Company of Saint Christopher (1626-1635), but would eventually be succeeded by the Company of the American Isles (1635-1664). The Indigenous population, called Caribbean Indians (Indiens caraïbes), were seen as naturalized French subjects, and were provided the same rights as French nationals upon their baptism. It was forbidden to enslave Indigenous peoples, or to sell them as slaves. Two populations were provided for: natural populations and native French, as the Edict of 1664 did not describe slaves or the importation of a black population. The French West India Company had gone bankrupt in 1674, with its commercial activities having been transferred to the Senegal Company and its territories returned to the Crown. The rulings of the Sovereign Council of Martinique patched the legal hole concerning slave populations. In 1652, at the behest of Jesuit missionaries, the Council reified the rule that slaves, like domestic servants, shall not be made to work on Sundays and in 1664, held that slaves would be required to be baptized and to attend catechism.[34]

The edict of 1685 ratified the practice of slavery despite the conflicting legislation of the Kingdom of France[35] and canon law.[36] In fact, an edict bringing emancipation in exchange for payment to the serfs of the King's domain, had been introduced on July 11, 1315 by Louis X the Stubborn, but had limited effect due to a lack of control of the King's officers and/or the fact that few serfs possessed sufficient funds to buy their liberty.[37] Such forms of indentured servitude existed up until the Edict for the suppression of the right of mortmain and of servitude in the domains of the King of August 8th, 1779, which was passed by Louis XVI, intended for certain regions that had recently become part of the kingdom.[38] The edict was not concerned with personal servitude, but rather real servitude or mortmain, which is to say that the denizen/owner could not sell or bequeath the land, as if the denizen/owner were only a renter. The lord possessed the droit de suite, meaning that the lord could retain any fee or proceeds resulting from the passing of the censive (the right to live on the estate and to pay tribute or cens to the lord).[39]

The King’s order through Colbert and the centrality of Martinique

[edit]Sick since 1681, Colbert died in 1683, less than two years after having transmitted the King’s order to the two successive intendants of Martinique, Patoulet and Bégon. Colbert’s son, the Marquis of Seignelay, signed the ordinance two years after his death.[40]

The colonial intendants’ work was centered in Martinique, where multiple nobles of the royal entourage had received estates and where Patoulet had requested Louis XIV to ennoble the plantation owners who owned more than one hundred slaves. The opinions recorded in the memoranda were entirely from Martinicans with no one from Guadeloupe, where métis and the large plantation owners were fewer.

The first letter from Colbert to intendant Patoulet and governor general of the Antilles Charles de Courbon, count of Blénac, reads:

“His Majesty finds it necessary to regulate, by declaration, all that concerns the negros of the isles, both for the punishment of their crimes and for all that might concern the justice to be dealt them. It is for this that it be necessary for you to create a memorandum as precise and extensive as possible, which considers all the cases having to do with said negros and which might merit regulation by an order. You must be well acquainted with the present customs of the isles as well as what should be customary in the future.”[41][42]

Posterity of the Code

[edit]Opinions about the Code

[edit]In his 1987 analysis of the Code Noir and its applications, Louis Sala-Molins, professor emeritus of political philosophy at Paris 1, argues that the Code Noir is the “most monstrous juridical text produced in modern times”.[43] According to Sala-Molins, the Code Noir served two purposes: to affirm “the sovereignty of the State in its farthest territories” and to create favorable conditions for the sugarcane commerce. “In this sense, the Code Noir foresaw a possible sugar hegemony for France in Europe. To achieve this goal, it was first necessary to condition the tool of the slave”.[25]

Sala-Molin’s theories have been critiqued by historians for lacking historical rigor and for relying on a selective reading of the Code.[44]

Nevertheless, the precise content of the 1685 edict remains uncertain, because, on one hand, the original has been lost[45] and on the other, there are often important variations between the surviving versions. Thus, it is necessary to compare them and understand which version was applicable to which colony or to each case, in order to accurately measure the impact of the Code Noir.[46]

Diderot, in a passage of Histoire des deux Indes, denounces slavery and imagines a large slave revolt orchestrated by a charismatic leader that leads to a complete reversal of the established order.

“Everywhere will the name of the hero who has restored the rights of the human species be blessed, everywhere will monuments be erected in his honor. And so the black code will disappear, but how terrible the white code shall be, should the victor consult only the law of reprisal!”[47]

Bernardin de Saint Pierre, who stayed in Ile de France from 1768 to 1770, highlighted the lag that existed between the creation of legislation and its institution.[48]

Enlightenment historian Jean Ehrard notes a typically colbertist method of regulating a phenomenon in the Code.[49] Slavery had been widespread in the colonies long before royal powers provided a legal framework for it. Ehrard noted that during the same era, one can find similar or equivalent dispositions to those in the Code Noir for other categories like for sailors, soldiers, and vagrants. Colonists were opposed to the Code because they were now compelled to provide slaves with a means of subsistence, which they normally were not required to guarantee.

Controversies of the Code’s legacy

[edit]Upon the 2015 release of his work Le Code noir. Idées reçues sur un texte symbolique, colonial law historian Jean-François Niort was attacked for his position that the authors of the Code intended for “a mediation between master and slave” by minor Guadeloupean political organizations self-styled as “patriotic” and accused of “racial discrimination” and denialism by some members of the Guadeloupean independantist movement who threatened to expel him from Guadeloupe.[50] He has been roundly supported by the historical community which has denounced the verbal and physical intimidation of specialists in the colonial history of the region.[51] The controversy continued in an argument in the opinions section of the French newspaper Le Monde between Niort and the philosopher Louis Sala-Molins.[52][53]

| This is a user sandbox of Enryonokatamarikun. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

- ^ "Le châtiment au Moyen Age". Histoires d'antan et d'à présent. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ Recueil de l'Académie de législation de Toulouse.

- ^ Gordien, Emmanuel (2013-02-11). "Les patronymes attribués aux anciens esclaves des colonies françaises. NON AN NOU, NON NOU, les livres des noms de familles antillaises". In Situ. Revue des patrimoines (in French) (20). ISSN 1630-7305.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - NiortConditionlibrecouleur.doc". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ a b La police des Noirs en Amérique (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guyane, Saint-Dominique) et en France aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. p. 67.

- ^ "La Louisiane française 1682-1803". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ "Ordonnance 1709". Mémoires des Montréalais (in French). Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ "Esclavage | Musée virtuel de la Nouvelle France". Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. FR CAOM COL C11A 30 fol. 334-335.

- ^ a b Frédéric Charlin, « », https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01926560/document, 2010, p. 45

- ^ "dossiers d'histoire - Victor Schoelcher - Sénat". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

{{cite web}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 40 (help) - ^ Lawrence C Jennings, « », Revue française d'histoire d'outre-mer, 1969, p. 375

- ^ Le Métissage dans la littérature des Antilles françaises, le complexe d'Ariel, Chantal Maignan-Claverie, Karthala Éditions, 2005 - 444 p.

- ^ Antoine Biet, Relation de voyages, 1664, cité par J. Petit Jean Roget, tome II, p. 1024.

- ^ Père Pelleprat, cité par J. Petit Jean Roget, tome II, p. 1022.

- ^ Merrill, Gordon. “The Role of Sephardic Jews in the British Caribbean Area During the Seventeenth Century.” Caribbean Studies, vol. 4, no. 3, Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico, 1964, pp. 32–49.

- ^ a b Maurouard, Elvire. Juifs de Martinique et Juifs Portugais sous Louis XIV. Éditions Du Cygne, 2009.

- ^ a b Breathett, George. “Catholicism and the Code Noir in Haiti.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 73, no. 1/4, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc, 1988, pp. 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1086/JNHv73n1-4p1.

- ^ Eric Saugera, Bordeaux port négrier, Karthala 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Sainton, Histoire et civilisation de la Caraïbe: Guadeloupe, Martinique, petites Antilles : la construction des sociétés antillaises des origines au temps présent, structures et dynamiques, sur Google Books, Maisonneuve et Larose, 6 septembre 2019.

- ^ Histoire et civilisation de la Caraïbe (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Petites Antilles) de Jean-Pierre Sainton et Raymond Boutin, page 318

- ^ Père du Tertre, Histoire générale des Antilles

- ^ Chantal Maignan-Claverie, Le métissage dans la littérature des Antilles françaises: le complexe d'Ariel, op. coté, p. 141

- ^ Yves Benot en contesta le caractère tranchant, « plus passionné que rationnel » qui à partir « d'un moralisme armé de son bon droit » ignore « la situation concrète, les obstacles socio-économiques », « le processus historique plus ou moins tortueux » comme le fait que « l'émancipation des opprimés doit (d'abord) être le fait des opprimés » in Yves Benot, La Révolution française et la fin des colonies, Paris, La découverte, 1987 p. 105-106.

- ^ a b "Historia Thématique". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ Breathett, George. “Catholicism and the Code Noir in Haiti.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 73, no. 1/4, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc, 1988, pp. 1–11.

- ^ David Bailie Warden, Nicolas Viton de Saint-Allais, Jean Baptiste Pierre Jullien de Courcelles et Agricol Joseph François Fortia d'Urban (marquis de), L'art de vérifier les dates : depuis l'année 1770 jusqu'à nos jours, vol. 39, Paris, 1837, 539 p, p. 528

- ^ Sébastien Louis Saulnier, « Revue britannique, publ. par mm. Saulnier fils et P. Dondey-Dupré », p. 142

- ^ « Histoire de la république des Etats-Unis depuis l'établissement des premières colonies jusqu'à l'élection du président Lincoln (1620-1860) » p. 446, (consulté le 6 septembre 2019)

- ^ The Law of slaves: a comparative Study of the Roman and Luisiana System, 1940.

- ^ Slave Law in America, 1985.

- ^ Law of slavery in spanish Luisiana 1769-1803.

- ^ Archives de l'Outre-Mer, à Aix-en-Provence, Col F/390.

- ^ Jacques Le Cornec, « Un royaume antillais: d'histoires et de rêves et de peuples mêlés», sur Google Books, L'Harmattan.

- ^ Les instructions du roi rédigées par Colbert rappellent que le droit de l'esclavage est « nouveau et inconnu dans le royaume ».

- ^ "Veritas ipsa", Wikipédia (in French), 2022-05-30, retrieved 2022-05-31

- ^ "Recueil général des anciennes lois françaises : depuis l'an 420 jusqu'à la révolution de 1789; contenant la notice des principaux monumens des Mérovingiens, des Carlovingiens et des Capétiens, et le texte des ordonnances, édits, déclarations, lettres-patentes, réglemens, arrêts du Conseil, etc., de la troisiéme race, qui ne sont pas abrogés, ou qui peuvent servir, soit à l'interprétation, soit à l'histoire du droit public et privé, avec notes de concordance, table chronologique et table générale analytique et alphabétique des matières : France. Laws, etc : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming". Internet Archive. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ Louis XVI, Édit du 8 août 1779 [archive], Paris, Imprimerie nationale, août 1779,

- ^ Lemarchand, Guy (2008-12-01). "Thierry Bressan, Serfs et mainmortables en France au XVIIIe siècle, la fin d'un archaïsme seigneurial". Annales historiques de la Révolution française (in French) (354): 223–225. ISSN 0003-4436.

- ^ Marie-Christine Rochmann, « Esclavage et abolitions: mémoires et systèmes de représentation : actes du colloque international de l'Université Paul Valéry, Montpellier III, 13 au 15 novembre 1998 »

- ^ La-Croix.com (2020-06-23). "Racisme et déboulonnement des statues : que reprocher à Colbert ?". La Croix (in French). Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ « Histoire de la martinique et de son esclavage » [archive], sur esclavage-martinique.com (consulté le 6 septembre 2019).

- ^ "Louis Sala-Molins : Le Code Noir ou le calvaire de Canaan". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ "Les travaux sur le Code noir ne doivent pas se plier aux dogmes". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2015-07-09. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ La plus ancienne version détenue par les Archives nationales semble être en effet l'édition Saugrain de 1718, dans le Guide des sources de la traite négrière, de l’esclavage et de leurs abolitions, dir. Claire Sibille. Paris : Direction des Archives de France / Documentation Française, 2007, 624 p., p. 37, 46-47. La version la plus ancienne de l'édit de mars 1685 connue à ce jour est celle enregistrée au Conseil supérieur de la Guadeloupe en décembre 1685, éditée récemment par J.-F. Niort aux éditions Dalloz (v. dans la bibliographie)

- ^ V. J.-F. Niort et J. Richard, « L'Édit royal de mars 1685 touchant la police des îles de l'Amérique française dit Code noir : versions choisies, comparées et commentées », revue Droits, no 50, 2010, p. 143-161. Accéder au texte en ligne sur le blog « Homo servilis et le Code noir » du site

- ^ Thomson, Ann (2003-10-15). "Diderot, Roubaud et l'esclavage". Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie (in French) (35): 69–94. ISSN 0769-0886.

- ^ «Il y a une loi faite en leur faveur appelée le Code Noir. Cette loi favorable ordonne qu’à chaque punition ils ne recevront pas plus de trente coups, qu’ils ne travailleront point le dimanche, qu’on leur donnera de la viande toutes les semaines, des chemises tous les ans ; mais on ne suit pas la Loi». Voyage à l’Isle de France, [1773], éd. augmentée d’inédits avec notes et index par Robert Chaudenson, Rose-Hill, Île Maurice : Éditions de l’Océan Indien, 1986, p. 176.

- ^ Jean Ehrard, , Bruxelles, André Versaille, 2008, 238 p. (ISBN 978-2-87495-006-3), second chapter.

- ^ dahomay, jacky. "Dénonçons la fatwa contre Jean-François Niort". Mediapart (in French). Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ Creoleways, Rédac (2015-04-10). "Code Noir : Jean-François Niort menacé, les historiens de Guadeloupe font bloc contre la censure". Creoleways (in French). Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ "Le Code Noir, une monstruosité qui mérite de l'histoire et non de l'idéologie". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2015-09-15. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ "Le « Code Noir » est bien une monstruosité". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2015-07-17. Retrieved 2022-05-31.