User:Ironholds/Aaron Burr, Sir

Ironholds/Aaron Burr, Sir | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1805 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | George Clinton |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1791 – March 4, 1797 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Schuyler |

| Succeeded by | Philip Schuyler |

| 3rd New York State Attorney General | |

| In office September 29, 1789 – November 8, 1791 | |

| Governor | George Clinton |

| Preceded by | Richard Varick |

| Succeeded by | Morgan Lewis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Aaron Burr Jr. February 6, 1756 Newark, Province of New Jersey, British America |

| Died | September 14, 1836 (aged 80) Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Princeton Cemetery, Princeton, New Jersey |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Theodosia Bartow Prevost (1782–1794) Eliza Jumel (1833–1836) |

| Alma mater | College of New Jersey |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775–1779 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

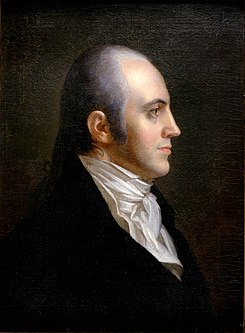

Aaron Burr, Jr. (February 6, 1756 – September 14, 1836) was an American politician. He was the third Vice President of the United States (1801–05); he served during President Thomas Jefferson's first term.

After serving as a Continental Army officer in the Revolutionary War, Burr became a successful lawyer and politician. He was elected twice to the New York State Assembly (1784–85, 1798–99),[1] was appointed New York State Attorney General (1789–91), was chosen as a United States Senator (1791–97) from the state of New York, and reached the apex of his career as vice president.

The highlight of Burr's tenure as President of the Senate (one of his few official duties as vice president) was the Senate's first impeachment trial, of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. In 1804, the last full year of his single term as vice president, Burr killed his political rival Alexander Hamilton in a famous duel. Burr was never tried for the illegal duel, and all charges against him were eventually dropped, but Hamilton's death ended Burr's political career.

After leaving Washington, Burr traveled west seeking new opportunities, both economic and political. His activities eventually led to his arrest on charges of treason in 1807. Although the subsequent trial resulted in acquittal, Burr's western schemes left him with large debts and few influential friends. In a final quest for grand opportunities, he left the United States for Europe. He remained overseas until 1812, when he returned to the United States to practice law in New York City. There he spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity.

Early life

[edit]Family and childhood

[edit]Aaron Burr was born on February 6, 1756, in Newark, New Jersey, to Aaron Burr, Sr. and Esther Edwards.[2] His family was "rather unusual, and extremely tight-knit";[3] his father was a Presbyterian minister and president of what is now Princeton University, noted for his powerful preaching. His mother was noted as a confident and brilliant conversationalist and writer, commenting on politics and religion and actively arguing with male tutors at her husband's college.[3] Her father, in turn, was Jonathan Edwards, a noted Calvinist "recognized as one of the most original minds of pre-revolutionary America".[4]

Burr, Sr. worked hard to make his college successful, writing to Europe soliciting funds and travelling around America giving speeches or sermons to get donations. After one such trip in 1757 he returned to discover that Jonathan Belcher, a supporter of the college and governor of New Jersey, had died. Burr became ill writing his funeral sermon, finding himself in a state of "intermittent fever", and delivered it almost delirious. Increasingly ill, he died on 24 September, while Burr was only 6 months old.[5] Burr himself then became ill, coming close to death, and although he survived his grandfather, Edwards, caught smallpox in March 1758 and passed away. Burr's mother, despite inoculation, died in the same way on 7 April - and her mother died of dysentery on 2 October. Before he was 2 years old, Burr had lost both his parents and grandparents.[6]

William Shippen, a Philadelphian friend of the Burrs, took Burr and his sister Sally in and moved them to Philadelphia. On 22 March 1760 their guardianship was transferred to Timothy Edwards, a cousin who was only 21 years old, and the children moved again to Elizabethtown, New Jersey.[7] There, Burr had trouble fitting in, becoming a rebellious and disruptive child; as well as brief attempts to leave he, aged ten, signed on as a cabin boy and was only tracked down and returned home with some difficulty.[8]

Education

[edit]Despite his rebelliousness, his uncle ensured he was properly educated. He was initially taught by Tapping Reeve, a tutor who later married Burr's sister, Sally.[9] When he was eleven he was tested for admission to Princeton College, but the tutors informed him he was too young and sent him away. Instead he studied the Princeton curriculum on his own, covering Greek and Latin grammar, rhetoric, logic and mathematics, and musical composition. Two years later, in 1769, he returned and requested admission as a third-year student, arguing that his independent study qualified him to skip the first two grades. Despite this, the examiners mandated that he enter as a second-year student.[10]

Four years younger than his classmates, Burr studied for up to 18 hours a day.[11] As well as his studies Burr also participated in the college clubs, the American Whig Society and the Cliosophic Society (which have now merged). Unusually for the time Burr was a member of both societies, building strong bonds with other students and honing his debating skills.[12] Noted for his charisma and popularity, Burr made several lifelong friendships at Princeton, including William Paterson who later signed the United States Constitution, Samuel Spring, and James Madison, future President of the United States.[13]

After his first set of exams, Burr "received such high grades that he concluded that little or no further study was necessary". Instead he spent his time participating in the clubs and socialising.[14] He graduated in September 1772, giving a commencement address titled Building Castles in the Air. Rather than leaving Princeton immediately after graduation, he lived on his parents' modest bequest and tried to identify a path for his life. As an educated man he was expected to become a lawyer, doctor or priest, and after a year of thought he moved to Bethlehem, Connecticut in 1773 to study under Joseph Bellamy, a "fire-and-brimstone preacher" as Burr's grandfather had been. After six months of intensive study, though, Burr decided to switch to the law, and moved to Litchfield to study with Tapping Reeve, his former tutor and brother-in-law.[15]

Soon after beginning his studies as a lawyer, the American Revolutionary War began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. "Ablaze with patriotism", Burr contacted his friend Matthias Ogden and pleaded that he join Burr in volunteering for the American army. After the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, both travelled to the American camp in Cambridge, Massachusetts to volunteer.[16]

Revolutionary War

[edit]Quebec expedition

[edit]

Burr arrived at the camp in Cambridge to find chaos, with officers democratically elected by enlisted men and a poorly structured and supplied army. Despite the presence of a British army across the river in Boston, there was effectively a stalemate, with soldiers fighting amongst themselves to relieve the boredom.[17] Soon after, however, a call went out for volunteers to form an army under Benedict Arnold in order to invade the British province of Quebec. Burr quickly volunteered, departing with the other 1,100 soldiers in September 1775. The force first travelled to Newburyport, Massachusetts and from there sailed up the Kennebec River.[18]

As winter approached, the soldiers making the 600-mile journey struggled to proceed. Food began to run out, with the men shooting and eating dogs; three companies turned back entirely. Burr, despite his youth and small stature, fared well, with his childhood spent hunting in the New Jersey marshes standing him in good stead.[19] In November the survivors - approximately 675 - were within 20 miles of Quebec City. Montreal had already been captured by an American army under Richard Montgomery, who quickly appointed Burr as his aide-de-camp and made him a Captain. The two armies combined, and began planning to attack the city. The initial plan was to attack on 27 December, but this order was rescinded due to clear weather: the commanders wanted a snowstorm to hide their advance.[20]

This appeared on December 31, and Montgomery advanced with Burr and his other aides besides him. No resistance was met at the start of the attack, which was mostly against volunteers, until a single cannon loaded with grapeshot was fired by a drunk sailor in a group of retreating civilians. The blast killed Montgomery and two of his aides, leaving only Burr and a French guide alive, and despite Burr's efforts to rally the rest of the army they were ordered to retreat.[21] The remaining soldiers spent the winter in Quebec, hoping for reinforcements, but the number that arrived were far outstripped by the number reinforcing the British defenders. Burr spent his time as brigade major to Arnold, describing the situation as "dirty" and "ragged"; eventually, with Arnold's blessing, he returned to the Thirteen Colonies, having heard that George Washington had offered him a place on his staff.[22]

Command

[edit]Burr reported to Washington's headquarters in New York in June 1776, but the general "took an instant dislike to Burr" and refused to accept him on to his personal staff. Instead Burr served as a clerk in his headquarters, and became so bored he wrote to John Hancock to tell him he was considering resigning. Hancock offered Burr the job of second in command with Israel Putnam, and after only 10 days of service with Washington, Burr departed to take up the position.[23]

Putnam and Burr quickly formed a strong bond, with Burr referring to him as "my good old general",[24] and he served as Putnam's primary aide during the British landing at Kip's Bay. As part of this he saved an entire brigade from encirclement and destruction: after the brigade's commander refused Putnam's suggestions to withdraw, Burr rode off as if to go back to Putnam's camp before returning claiming he'd received orders demanding the withdrawal.[25] Many stories say that Alexander Hamilton was serving with the regiment, and so Burr knowingly saved his life, but some biographers question if this actually happened, on the basis that if Burr had rescued Hamilton one would expect him to brag or mention it after the war. Instead, Burr's only retelling of the incident ignored Hamilton entirely.[26]

On 209 June 1777, Burr received his first formal commission and command, as a Lieutenant Colonel leading Malcolm's Additional Continental Regiment, nominally commanded by William Malcolm. He found the "Malcolms" tremendously understaffed and began trying to recruit more soldiers, increasing the size of his regiment from 300 to 500, and instituted a strong training and disciplinary regime:[27] a regimental officer reported the Malcolms to be "a model for the whole army in discipline and order".[28] It was while serving with the Malcolms that Burr met Theodosia Prevost, the wife of a British officer serving in the Caribbean; the two quickly fell in love.[29]

The Malcolms, with Burr leading them, fought at the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. Burr led the regiment to attack a group of redcoats before orders arrived from Washington ordering them to hold in place. As a result the regiment was left in a muddy ditch exposed to the enemy: Burr's second in command was hit with a cannonball, while Burr himself had his horse shot out from under him. The regiment stood for hours in 96 degree heat, with the "glowering sun and...leaden air" killing almost as many of them as enemy fire.[30]

Later service and retirement

[edit]Burr became seriously ill due to the heatstroke he suffered at Monmouth, and was forced to take a break. When he returned to active duty it was to serve as part of the garrison at West Point, New York, where he oversaw courts-martial and did his best to instil discipline in a camp suffering from a "spirit of discord".[31] Burr was then transferred to Westchester County in January 1779, serving under General Alexander McDougall and operating to disrupt bandits in the area.[32]

On arrival Burr found guerilla warfare and corruption; the camp was "filled with stolen goods and animals", and he wrote to McDougall that he wished he could "gibbet half a dozen good [Patriots] with all the venom of an inveterate [Loyalist]".[33] He immediately ensured all stolen goods were returned to their owners, regardless of their owner's allegiance, and began to reform the soldiers' behaviour.[33] While in Westchester he recruited a volunteer intelligence staff; civilians spying for the Army to identify enemy troop movements, bandit activity and corruption. At the same time he built a register of all local civilians, identifying their allegiance, and a map that noted the roads most commonly used by bandits or thieves. Traffic monitoring was put in place to identify the flow in and out of British-controlled territory, particularly prostitutes, who he felt acted as spies.[34]

While effective, maintaining this system was a strain on someone still ill after Monmouth - something that would affect him for the rest of his life - and observing the corruption of the American soldiers sapped his morale. On February 18, 1779, Burr wrote to McDougall expressing his desire to retire from the army, and his confidence that the spy network and other projects were robust enough to survive him. On March 25 he wrote to Washington, saying that his health was "no longer equal to the severities of active Service", and resigning.[35] His resignation did not entirely mark the end of his Revolutionary War activities: over the next few months he found himself carrying orders from McDougall and Arthur St. Clair as he travelled, and organised a group of Yale College students and militia in New Haven when the British attacked, holding them off for long enough that most of the non-combatants could escape.[36]

Politics and the law

[edit]After leaving the Army, Burr's

Legal practice

[edit]Early political career

[edit]Vice-Presidency

[edit]Burr-Hamilton duel

[edit]Burr conspiracy

[edit]Conspiracy

[edit]Trial

[edit]Later life

[edit]Death

[edit]Character

[edit]Legacy

[edit]Representation in literature and popular culture

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ OOA & n.d.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, p. 3.

- ^ a b Isenberg 2007, p. 4.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 4.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 18.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 20.

- ^ St. George 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 24-5.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 27–8.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 26.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 34–5.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 36.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 37.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 39.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 40.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 41.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 42–3.

- ^ St. George 2009, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 45.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 49.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 52–4.

- ^ St. George 2009, p. 33.

- ^ St. George 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Lomask 1979, pp. 56–8.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, pp. 48–9.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, pp. 49.

- ^ a b Lomask 1979, p. 61.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, pp. 51.

- ^ Isenberg 2007, pp. 52.

- ^ Lomask 1979, p. 63.

Bibliography

[edit]- Isenberg, Nancy (2007). Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143113713.

- Lomask, Milton (1979). Aaron Burr: The Years from Princeton to Vice President, 1756-1805. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0374100160.

- St. George, Judith (2009). The Duel: The Parallel Lives of Alexander Hamilton & Aaron Burr. Viking. ISBN 9780670011247.