User talk:Toddy1/Sandbox 17

Model of Océan on display at the Musée de la Marine, Paris

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Océan class |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Provence class |

| Succeeded by | Friedland |

| Built | 1865–1875 |

| In service | 1870–1897 |

| In commission | 1870–1895 |

| Completed | 3 |

| Scrapped | 3 |

| General characteristics (Océan as built) | |

| Type | Ironclad |

| Displacement | 7,749 t (7,627 long tons) |

| Length | 86.2 m (282 ft 10 in) |

| Beam | 17.52 m (57 ft 6 in) |

| Draft | 9.09 m (29.8 ft) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft; 1 compound steam engine |

| Sail plan | Barque or barquentine-rig |

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) |

| Range | approximately 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 750–778 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

The Océan-class ironclads were a class of three wooden-hulled armored frigates built for the French Navy in the mid to late 1860s. Océan attempted to blockade Prussian ports in the Baltic Sea in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War and Marengo participated in the French conquest of Tunisia in 1881. Suffren was often used as the flagship for the Cherbourg Division, the Channel Division, Mediterranean Squadron and the Northern Squadron during her career. The ships were discarded during the 1890s.

An innovation in the Océan-class was that part of the main armament was mounted in barbettes. French officers who commanded these ships were very pleased with the barbette guns, and spoke "particularly of the very large offensive power that it gave them; that it not only gave them a large arc of fire, but... they dwelt upon the possibility of seeing the enemy at the the points of your sights the whole way round, even when you had an obstruction in the shape of rigging which prevented firing, instead of having been at one moment hidden from you by the superstructure forward, and then next moment suddenly appearing in sight, through a narrow port, where your eye is almost blinded with light, and where you are not in a position to recognise the presence of the object till it has been for some seconds within your range of view."[1]

Design and description[edit]

The Océan-class ironclads were designed by Henri Dupuy de Lôme as an improved version of the Provence-class ironclads. The ships were central battery ironclads with the armament concentrated amidships.[2]

For the first time in a French ironclad three watertight iron bulkheads were fitted in the hull, but they probably of little value in a wooden-hulled ship.[3][4] "[W]ooden hulls lacked the structural rigidity of iron and could not, therefore, have effective internal compartmentalization."[5]

Like most ironclads of their era they were equipped with a metal-reinforced ram.[3]

The ships measured 87.73 meters (287 ft 10 in) overall,[3] with a beam of 17.52 meters (57 ft 6 in). They had a maximum draft of 9.09 meters (29 ft 10 in) and displaced 7,749 metric tons (7,627 long tons).[2] Their crew numbered between 750 and 778 officers and men. The metacentric height of the ships was very low, between 1.7–2.2 feet (0.5–0.7 m).[3] The ships were over-weight as completed; their draught so exceeded that designed for them that an increase of stability by ballast was impossible.[6] The Océan-class were reported to be able to carry all sail safely, were good sea-boats, steady and well-behaved, but lacking in stiffness (resistance to heeling).[6]

Weights[edit]

| Marengo: breakdown of displacement[7] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hull | Armour and its fixings | Machinery and boilers | Fuel and stores | Masts, rigging, and stores | Crew | Armament, including mountings and ammunition | Total | |

| Tonnes (Long Tons) |

3,662 (3,604) |

1,380 (1,360) |

895 (881) |

618 (608) |

393 (387) |

280 (280) |

520 (510) |

7,748 (7,626) |

| 47% | 18% | 12% | 8% | 5% | 4% | 7% | 100% | |

According to Nathaniel Barnaby (Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy) in 1872, the Océan-class ships had 1,300 tonnes (1,280 long tons) of armour.[8]

Naval architects expect the weight of machinery to be proportional to the power for similar compound-engines.[9] It is difficult to understand why ratio of power to machinery weight was so much lower for the Marengo than for contemporary British ironclads. Perhaps the French figures included weights that were not included in the British figures.

| Ship | Engine power ihp |

Machinery weight (including boilers) long ton |

ihp/ton | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marengo | 3,673 | 895 | 4.1 | ,[10][11] |

| HMS Hercules | 6,750 | 1,206 | 5.6 | ,[12][13] |

| HMS Thunderer | 6,270 | 1,050 | 6.0 | [14] |

Propulsion[edit]

The Océan-class ships had a horizontal-return, connecting-rod, compound steam engine, driving a single propeller using steam provided by eight oval boilers.[3] Indret made the engines for Océan and Marengo; Schneider made the engines for Suffren.[15] On sea trials the engines produced between 3,600–4,100 indicated horsepower (2,700–3,100 kW) and the ships reached 13.5–14.3 knots (25.0–26.5 km/h; 15.5–16.5 mph).[15] They carried 650 metric tons (640 long tons)[3] of coal which allowed them to steam for approximately 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[15]

| Comparison of designed performance and trial results.[16] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement[10] | Maximum speed[10] | Power[10] | Engine[10] | ||||

| tonnes | long tons | knots | km/hr | ihp | kW | rpm | |

| Design | 14.0 | 25.9 | 4,500 | 3,400 | 65 | ||

| Océan | 7,749 | 7,627 | 13.7 | 25.4 | 3,781 | 2,819 | 55 |

| Marengo | 7,476 | 7,358 | 13.6 | 25.2 | 3,673 | 2,739 | - |

| Suffren | 7,780 | 7,660 | 14.3 | 26.5 | 4,181 | 3,118 | - |

The Océan-class ships were barque or barquentine-rigged with three masts and had a sail area around 2,000 square meters (22,000 sq ft).[3] The rigging of the foremast and mizzenmast were brought down to plates, tied under the main deck beams.[17] Later in life, the rig was reduced and fighting tops were added to the main and mizzen masts.[4]

Armament[edit]

The initial design was to have a main armament of four 19 cm (7.5 in) guns and four 16 cm (6.3 in) guns on the main deck in an armoured central battery, and four 24-centimeter (9.4 in) guns in open-topped armoured barbettes on the spar deck.[18][16] In 1869, the armament was changed to four 24 cm guns in barbettes and either six or eight 24 cm guns in the battery,[18][16] which was then changed to four 24 cm guns in barbettes and four 27 cm (10.8 in) cm guns in the battery,[18][16][19] The ship's sides were not recessed, so the main deck guns could not fire fore or aft. But the barbettes were slightly sponsoned out over the sides of the hull.[19] If the barbette guns were fired at angles smaller than 45 degrees from the keel-line, the crew had to be withdrawn from the extremities of the ship; for practical purposes, the arc of fire of each barbette was about 100 degrees.[19][a] The main deck battery was 3.9 m (13 ft) above the waterline and the spar deck and barbette guns were 8.3 m (27 ft) above the waterline.[16] The barbettes had steam-powered turntables.[18] The depression of the guns was not sufficient for plunging fire on the deck of an enemy ship at very close quarters.[21] Elevation of the barbette guns was considered very good, and allowed the Océan at engage targets at 4,900 m (5,400 yd),[21] with Model 1864-67 guns whose muzzle velocity was only 340 m/s (1,115 ft/s).[22]

They also had a secondary armament mounted on the broadside on the spar deck of six 14 cm (5.5 in)[4] or 12 cm (4.7 in) guns,[18][19][23] the rear pair could be moved to the stern to fire aft.[19]

At some point the ships received a dozen 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss 5-barrel revolving guns.[3][4] They fired a shell weighing about 500 g (1.1 lb) with a muzzle velocity of about 610 m/s (2,000 ft/s) to a range of about 3,200 m (3,500 yd). They had a rate of fire of about 30 rounds per minute.[24] Late in the ships' careers four above-water 356-millimeter (14.0 in) torpedo tubes were added.[3][4]

French Model 1864 and 1870 naval guns were breechloaders made of cast iron, lined with steel as far as the trunnions, reinforced externally from the breech to the trunnions by rings of puddled steel shrunk onto the body.[26] The breech mechanism was an interrupted screw.[26] The construction of Model 1870 differed from Model 1864, and allowed greater pressures, and thus higher muzzle velocity.[27]

The Model 1864 came into service in the French Navy in 1867.[27]

Manufacture of Model 1870 guns began after the Franco-Prussian War ended in 1871.[26] Model 1870 guns had polygroove rifling, which by the standards of 1870s naval guns was very advanced.[26] They also had enlarged chamber for the propellant, which again was advanced for the 1870s.[26] The endurance of Model 1870 guns was said to be very great. These guns were less expensive than contemporary British naval guns; for example the 24 cm Model 1870 cost about £580, whereas the nearest equivalent British naval gun cost about £740.[26][b]

- 27 cm Model 1870: weight 23 tonnes (23 long tons), overall length 5.4 m (212 in), bore length 4.9 m (194 in) 18 calibres long, rifling 28 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron or steel shell: projectile 215 kg (475 lb), propellant 41.9 kg (92.4 lb), muzzle velocity 432 m/s (1,417 ft/s), muzzle energy 20.03 MJ (6,596 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 320 mm (12.5 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 180 kg (396 lb), bursting charge 11 kg (24 lb), propellant 41.9 kg (92.4 lb), muzzle velocity 470 m/s (1,542 ft/s), muzzle energy 19.76 MJ (6,506 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 144 kg (317 lb)

- 24 cm Model 1870: weight 15.7 tonnes (15.5 long tons), overall length 5.0 m (195 in), bore length 4.5 m (179 in) 19 calibres long, rifling 24 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron or steel shell: projectile 144 kg (317 lb), propellant 27.9 kg (61.6 lb), muzzle velocity 440 m/s (1,443 ft/s), muzzle energy 13.95 MJ (4,561 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 280 mm (11.1 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 120 kg (264 lb), bursting charge 7.7 kg (17 lb), propellant 27.9 kg (61.6 lb), muzzle velocity 474 m/s (1,555 ft/s), muzzle energy 13.41 MJ (4,414 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 100 kg (220 lb)

- 27 cm Model 1864: weight 20 tonnes (20 long tons), overall length 4.7 m (184 in), bore length 4.2 m (167 in) 15 calibres long, rifling 5 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron shell: projectile 215 kg (475 lb), propellant 35.9 kg (79.2 lb), muzzle velocity 331 m/s (1,086 ft/s), muzzle energy 11.76 MJ (3,871 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 320 mm (12.5 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 144 kg (317 lb), bursting charge 6.6 kg (14.6 lb), propellant 23.9 kg (52.8 lb), muzzle velocity 362 m/s (1,188 ft/s), muzzle energy 9.38 MJ (3,088 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 146 kg (321 lb)

- 24 cm Model 1864: weight 14 tonnes (14 long tons), overall length 4.6 m (180 in), bore length 4.2 m (165 in) 17 calibres long, rifling 5 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron shell: projectile 144 kg (317 lb), propellant 23.9 kg (52.8 lb), muzzle velocity 340 m/s (1,115 ft/s), muzzle energy 8.57 MJ (2,821 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 280 mm (11.1 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 100 kg (220 lb), bursting charge 4.7 kg (10.3 lb), propellant 16.0 kg (35.2 lb), muzzle velocity 362 m/s (1,188 ft/s), muzzle energy 6.51 MJ (2,144 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 96 kg (211 lb) or 100 kg (220 lb)

- 19 cm Model 1864: weight 7.87 tonnes (7.75 long tons), overall length 3.8 m (150 in), bore length 3.5 m (138 in) 18 calibres long, rifling 5 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron shell: projectile 75 kg (165 lb), propellant 12.5 kg (27.5 lb), muzzle velocity 344 m/s (1,128 ft/s), muzzle energy 4.41 MJ (1,451 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 180 mm (7.0 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 52 kg (115 lb), bursting charge 2.2 kg (4.8 lb), propellant 8.0 kg (17.6 lb), muzzle velocity 356 m/s (1,168 ft/s), muzzle energy 3.28 MJ (1,081 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 48 kg (105 lb)

- 16 cm Model 1864: weight 4.83 tonnes (4.75 long tons), overall length 3.4 m (133 in), bore length 3.1 m (124 in) 19 calibres long, rifling 3 grooves:[22]

- Chilled iron shell: projectile 45 kg (99 lb), propellant 7.5 kg (16.5 lb), muzzle velocity 345 m/s (1,132 ft/s), muzzle energy 2.66 MJ (876 foot tons), penetration of wrought iron armour 149 mm (5.87 in)

- Common shell (cast iron): projectile 31 kg (69 lb), bursting charge 1.4 kg (3 lb), propellant 5.0 kg (11 lb), muzzle velocity 365 m/s (1,197 ft/s), muzzle energy 2.09 MJ (687 foot tons)

- Canister: projectile 30 kg (66 lb) or 100 kg (220 lb)

The chilled iron shells were similar to British Palliser shells. The French started to manufacture cast steel armour-piercing shells in the mid-1870s. These were followed by forged steel armour-piercing shells, and in 1886 Holtzer produced the first chromium-steel armour-piercing shells.[29][c]

In the 1870s, the propellant used by the French Navy was Wetteren Powder, which was made up of 75% saltpetre, 10% sulphur, and 15% charcoal. During manufacture, the propellant was mixed, then made into a cake, which was cut into a standard grain size that varied with the calibre of gun:[30]

- 27 cm: 57 grains per kg (26 per lb)

- 24 cm: 110 grains per kg (50 per lb)

- 19 cm: 227 grains per kg (103 per lb)

- 16 cm: 362 grains per kg (164 per lb)

- 12 cm: 710 grains per kg (322 per lb)

Océan's armament over time[edit]

| When | Barbette | Armoured battery | Spar deck, tops, etc. | Torpedo launchers |

Source | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 cm | 27 cm | 24 cm | 19 cm | 16 cm | 14 cm | 12 cm | QF | MG | |||

| Design | 4 | 4 | 4 | [18][16] | |||||||

| 1869 | 4 | 6 or 8 | [18][16] | ||||||||

| Later | 4 | 4 | 6 | [18][19] | |||||||

| 1878 | 4 | 4 | some | [31] | |||||||

| 1886 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | [11] | ||||||

| 1887 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | [32] | ||||||

| 1888-9 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | [33] | ||||||

| 1890 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | [34] | ||||||

| 1891 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | [35] | ||||||

| 1892 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | [36] | ||||||

| 1893 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 12 | [37] | |||||

| 1894 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 12 | [38] | |||||

| 1895 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 4 | [39] | ||||

| 1896 | Océan not listed | [40] | |||||||||

Armor[edit]

The Ocean-class ships had a complete 178–203-millimeter (7–8 in) waterline belt of wrought iron. The sides of the battery itself were armored with 160 millimeters (6.3 in) of wrought iron. The barbette armor was 150 millimeters (5.9 in) thick. The unarmored portions of their sides were protected by 15-millimeter (0.6 in) iron plates. Gardiner and Gibbons say that the barbette armor was later removed to improve their stability,[3][4] but this is not confirmed by any other source.[2][15]

-

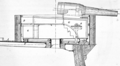

Armour and armament distribution on the Océan class

-

Barbette of the Océan class

A Upper deck

a Backing

B Barbette

b Inner skin

C Pivot hollow for supply of ammunition

D Ring revolving on pivot

E Rollers

G Slide and carriage

I Platform for working gun

K Toothed rack

L, M, N, O Turning gear -

Section through the hull of French Ocean-class ironclad showing side armour and decks

-

Marengo on 26 May 1888

-

Suffren circa 1875

Ships[edit]

| Ship | Builder [16] | Laid down [16] | Launched [16] | Commissioned for trials [16] | Commissioned for service[16] | Fate [2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Océan | Arsenal de Brest | 18 April 1865 (or July 1865)[2][3] |

15 October 1868 | December 1869 | 15 July 1870 (or 21 July 1870)[2][3] |

Condemned 1894 |

| Marengo | Arsenal de Toulon | 20 February 1865 (or July 1865)[2][3] |

4 December 1869 | July 1870 | 1 May 1872 | Condemned 1896 |

| Suffren | Arsenal de Cherbourg | 26 April 1866 (or July 1866)[2][3] |

26 December 1872 | January 1873 | 19 April 1873 (or 1875 or 1 March 1876)[2][3] |

Condemned 1897 |

Initial cost[edit]

The American, Chief Engineer James Wilson King, gave the cost of each ship as $1,302,000 for the hull and machinery excluding armament, rigging and first outfit of stores, and $260,680 for machinery alone.[41] Thomas Brassey gave the cost of the Marengo as £280,000,[42][43] and the Suffren as £260,400.[42]

Service[edit]

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 Océan was assigned to the Northern Squadron that attempted to blockade German ports.[44] When part of the French fleet went through the Kattegat and the Great Belt to get into the Baltic in August 1870, the Océan's draft of 28 feet meant that at times she only had 1 1/2 feet of water under her keel.[45] On 17 August, the French squadron tried to engage a group of German gunboats (the Grille, Drache, Blitz and Salamander) that were anchored 4,900 m (5,400 yd) from the French squadron at the head of the Bay of Wittow (a bay in the island of Rügen); only the Océan's barbette guns had sufficient range to open fire. After six shots from the Océan, the German gunboats retreated through the Seegat and reached safety near Wittow Posthaus.[21][46] Eventually Vice-Admiral Édouard Bouët-Willaumez decided that the Océan had too deep a draft for blocade duties in the Baltic and sent her back to the North Sea.[47] On 16 September 1870, the Northern Squadron was ordered to return to Cherbourg.[44] Afterward she was assigned to the Evolutionary Squadron until 1875 when she was placed in reserve. Océan was recommissioned in 1879 for service with the Mediterranean Squadron. She had a lengthy refit in 1884–85 and was assigned to the Northern Squadron after it was completed. Around 1888 the ship was transferred back to the Mediterranean Squadron until she was reduced to reserve around 1891. Océan was assigned to the Gunnery School that same year and later became a training ship for naval apprentices before being condemned in 1894.[2]

Marengo was running her sea trials when the Franco-Prussian War began and was immediately put in reserve. She was recommissioned in 1872 for service with the Mediterranean Squadron until 1876 when she was again placed in reserve. On 2 October 1880 the ship was recommissioned and assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron. Marengo was transferred to the Levant Squadron (French: Division Navale du Levant) on 13 February 1881[48] and bombarded the Tunisian port of Sfax in July 1881 as part of the French conquest of Tunisia.[49] She remained in the Mediterranean until she was assigned to the Reserve Squadron in 1886. In 1888 Marengo became the flagship of the Northern Squadron and led the squadron during its port visit to Kronstadt in 1891.[50] She was reduced to reserve the following year and sold in 1896.[48]

Suffren was placed into reserve after she completed her sea trials and was not commissioned until 1 March 1876 when she became flagship of the Cherbourg Division. Throughout her career the ship was often used as a flagship because of her spacious admiral's quarters. On 1 September 1880[2] the ship was assigned to the division that participated in the international naval demonstration at Ragusa later that month under the command of Vice Admiral Seymour of the Royal Navy in an attempt to force the Ottoman Empire to comply with the terms of the Treaty of Berlin and turn over the town of Ulcinj to Montenegro.[51] Suffren was reduced to reserve in 1881 and not recommissioned until 23 August 1884 when she was assigned to the Northern Squadron. The ship was transferred to the Mediterranean Squadron about 1888 and remained there until paid off in 1895 and condemned in 1897.[2]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Baron Grivel, who had been captain of the Océan wrote: "The fire of the guns placed in the turrets [barbettes] in a line with the keel, to which much had been sacrificed both in the spread of the shrouds, the position of the boats, and the arrangement of the bulwarks, and last, not least, the light armament of the upper deck, appears to me a perfect chimera. The Commission appointed to carry out experiments were so much struck with the injury occasioned by the concussion from a 24 c/m., or 15½-ton, gun that they determined that the guns should not be trained within 15° of the line of the keel. The shrouds and boats at the davits had been covered up with wet canvas, and yet the force of the explosions was such that the greater numbers of the rivets near the upper deck were fractured, and two boats were so much injured as to be rendered unfit for use. Moreover, the fire of the foremost turret [barbette] could not converge with that of the aftermost turret [barbette] at close quarters without danger to the guns' crews. It would appear wise to fire the guns parallel with one another, or at least to attempt a converging fire only at a considerable distance. When firing within less than an angle of 45° with the keel line, the crews should be withdrawn from the extremities of the ship, on the side from which fire is being directed, and the men absolutely forbidden from passing near the bulwarks on that side of the ship."[20]

- ^ The cost of contemporary British naval guns were as follows:[28]

- RML 12-inch 35-ton gun £2,153 13s 9d

- RML 12-inch 25-ton gun £1,715 13s 5d

- RML 10-inch 18-ton gun £1,005 10s 2d

- RML 9-inch 12-ton gun £738 17s 8d

- RML 8-inch 9-ton gun £567 12s 10d

- RML 7-inch 6½-ton gun £424 11s 10d

- ^ Chromium-steel armour-piercing shells contained about 1-2% chromium.[29] Stainless steel has at least 11% chromium.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Brassey, Thomas (1883). The British Navy, Volume III. pp. 55–6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l de Balincourt, Captain; Vincent-Bréchignac, Captain (1975). "The French Navy of Yesterday: Ironclad Frigates, Part IV": 26–27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. p. 288.

- ^ a b c d e f Gibbons, Tony (1983). The complete encyclopedia of battleships and battlecruisers. pp. 76–77.

- ^ Beeler, John F. (1997). British Naval Policy in the Gladstone-Disraeli Era 1866–1880. p. 204.

- ^ a b Fishbourne, Edmund Gardiner (1874). Our ironclads and merchant ships. pp. 21, 26.

- ^ Gille, Eric (1999). Cent Ans de cuirassés français. p. 153.

The meaning of the column headings were elucidated with the aid of:

Saibene, Marc (1996). Les Cuirasses Redoutable, Devastation et Courbet : Programme de 1872. pp. 18, 58, 72.

Saibene, Mark (1994), "The Redoutable", Warship International, no. 1 - ^ Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume I. p. 103. This quoted from a paper presented by Nathaniel Barnaby at RUSI on 29 January 1872.

- ^ Brown, David K (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development, 1860-1905. p. 206.

- ^ a b c d e Gille, Eric (1999). Cent Ans de cuirassés français. p. 158.

- ^ a b Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1886). The Naval Annual 1886. p. 226.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Reed, Edward James. Our Ironclad Ships, their Qualities, Performance and Cost. p. 105.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1886). The Naval Annual 1886. p. 158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brown, David K (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development, 1860-1905. p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gille, Eric (1999). Cent Ans de cuirassés français. pp. 30–32.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas (1883). The British Navy, Volume III. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Friedman, Norman (2018). British battleships of the Victorian era. pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b c d e f Hovgaard, William (1920). Modern History of warships. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Baron Grivel (1872), Revue Maritime, vol. ii quoted in translation in Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume I. p. 24.

- ^ a b c Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume I. pp. 24–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume II. pp. 106–7.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas (1883). The British Navy, Volume III. pp. 32–3.

- ^ "United States of America 1-pdr (0.45 kg) 1.46" (37 mm) Marks 1 through 15". Navweps.com. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ "Conon de Marine de 24cm Mle 1864"La Valérie"", Traces of War, retrieved 26 November 2019

- ^ a b c d e f Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume II. pp. 55–6.

- ^ a b Hovgaard, William (1920). Modern History of warships. p. 396.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume II. p. 38.

- ^ a b Hovgaard, William (1920). Modern History of warships. pp. 433–5.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume II. p. 59.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. p. 226.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1889). The Naval Annual 1888-9. p. 294.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1890). The Naval Annual 1890. p. 286.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1891). The Naval Annual 1891. p. 212.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1892). The Naval Annual 1892. p. 213.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1893). The Naval Annual 1893. p. 223.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1894). The Naval Annual 1894. p. 287.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1895). The Naval Annual 1895. p. 259.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1896). The Naval Annual 1896. p. 233.

- ^ King, James Wilson (1881). The War-Ships and Navies of the World. p. 9.

- ^ Brassey, Thomas. The Naval Annual 1887.

- ^ a b de Balincourt and Vincent-Bréchignac 1975, p. 30

- ^ Rüstow, Wilhelm (1872). The War for the Rhine Frontier, 1870, Volume 3. Translated by Needham, John Layland. p. 235.

- ^ German General Staff (1876). The Franco-German War 1870-71. Vol. 2. Translated by Clarke, F C H. p. 423. This appears to be describing the same incident as described by Brassey, though it does not mention the French ship Océan.

- ^ Rüstow, Wilhelm (1872). The War for the Rhine Frontier, 1870, Volume 3. Translated by Needham, John Layland. p. 239.

- ^ a b de Balincourt and Vincent-Bréchignac 1975, pp. 26–27

- ^ Wilson, H. W. (1896). Ironclads in Action. Vol. Volume 2. pp. 3–4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Sedgewick, p. 3

- ^ McCarthy, Justin Huntly (2006). England Under Gladstone, 1880–1884. pp. 56–58.

References[edit]

- de Balincourt, Captain; Vincent-Bréchignac, Captain (1975). "The French Navy of Yesterday: Ironclad Frigates, Part IV". F.P.D.S. Newsletter. III (4). Akron, OH: F.P.D.S.: 26–30.

- Beeler, John F. (1997). British Naval Policy in the Gladstone-Disraeli Era 1866–1880. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804729819.

- Beeler, John F. (2001). Birth of the Battleship: British Capital Ship Design, 1870-1881. Great Britain: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1840675349.

- Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume I, shipbuilding for the purposes of war. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

- Brassey, Thomas (1882). The British Navy, Volume II, miscellaneous subjects connected with ship-building for the purposes of war. London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

- Brassey, Thomas (1883). The British Navy, Volume III, opinions of the shipbuilding policy of the navy (2 ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Company.

- Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1886). The Naval Annual 1886. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1889). The Naval Annual 1888-9. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1890). The Naval Annual 1890. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, Lord, ed. (1891). The Naval Annual 1891. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1892). The Naval Annual 1892. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1893). The Naval Annual 1893. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1894). The Naval Annual 1894. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1895). The Naval Annual 1895. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

- Brassey, Thomas A, ed. (1896). The Naval Annual 1896. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

- Brown, David K (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development, 1860-1905. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-022-1.

- Fishbourne, Edmund Gardiner (1874). Our ironclads and merchant ships. London: E & F N Spon.

- Friedman, Norman (2018). British Battleships of the Victorian Era. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1526703255.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4. None that the chapter on French warships was by N. John M. Campbell.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers. Salamander Books. ISBN 978-0861011421.

- German General Staff (1876). The Franco-German War 1870-71. Vol. 2. Translated by Clarke, F C H.

- Gille, Eric (September 1999). Cent Ans de Cuirassés Français. Nantes: Marines Editions. ISBN 978-2909675503.

- Hovgaard, William (1978) [1920]. Modern History of warships. Conway Maritime Press.

- King, James Wilson (1881). The War-Ships and Navies of the World. Boston: A Williams and Company.

- McCarthy, Justin Huntly (2006). England Under Gladstone, 1880–1884 (reprint of 1884 ed.). London: Elibron Classics. ISBN 9780543914989.

- Randier, Jean (1972). La Royale, l'Éperon et la Cuirasse. Brest, France: Éditions de la cité.

- Reed, Edward James (1869). Our Ironclad Ships, their Qualities, Performance and Cost. John Murray.

- Rüstow, Wilhelm (1872). The War for the Rhine Frontier, 1870: Its Political and Military History, Volume 3. Translated by Needham, John Layland. Edinburgh and London: William Backwood and Sons.

- Sedgwick, Alexander (1965). The Ralliement in French Politics, 1890–1898. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674747517.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Wilson, H. W. (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare From 1855 to 1895. Vol. Volume 2. Boston: Little, Brown.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - "Maquette de bateau, Océan, cuirassé d'escadre, 1868" [Ship model, Océan, battleship, 1868], Musée national de la Marine, retrieved 17 November 2019

- "Frégates cuirassées Océan" [Central battery ships Ocean], La flotte de Napoléon III, retrieved 17 November 2019