Wilhelma

- For the Templer settlement, see Wilhelma, Palestine

| Wilhelma Zoological-Botanical Garden Stuttgart | |

|---|---|

(German: Wilhelma Zoologisch-Botanischer Garten Stuttgart) | |

Logo of Wilhelma Zoo and Botanical Garden | |

Wilhelma Zoo circa 1900 | |

| Alternative names | Schloss Wilhelma |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Zoo |

| Architectural style | Moorish Revival |

| Classification | Zoo |

| Location | Bad Cannstatt District, Baden-Württemberg |

| Town or city | Stuttgart |

| Country | Germany |

| Coordinates | 48°48′19″N 9°12′11″E / 48.80528°N 9.20306°E |

| Opened | 1919 (as a botanical garden),[1] 1951 (first animal exhibit)[2] |

| Client | Wilhelma Zoo[3] |

| Owner | Baden-Württemberg, Ministry of Finance[3] |

| Landlord | Baden-Württemberg, Ministry of Finance[3] |

| Affiliation | Department of Real Estate and Buildings[3] |

| Grounds | 30 hectares (74 acres)[1] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ludwig von Zanth |

| Known for | Wilbär the polar bear, accidentally breeding of a virulent strain of Caulerpa taxifolia[4] |

is a zoological-botanical garden in Stuttgart in the Bad Cannstatt District in the north of the city on the grounds of a historic castle. Wilhelma Zoo is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Baden-Württemberg, seeing more than 2 million visitors annually.[5]

The Zoo and Botanical Garden have been staffed since 1846.[6] The Moorish Revival style echoing the Alhambra have been maintained and supplemented since 1960. Today, the zoo has an area of about 30 hectares (0.30 km2), houses around 11,500 animals from around the world composed of roughly 1,200 species and roughly 6000 plants from all climates.[7] Of Germany's zoos, Wilhelma's collection ranks second only to the Berlin Zoological Garden.[3] In addition to the public garden, Wilhelma also has a branch office located in Fellbach, where the zoo keeps its stallions.[8]

Wilhelma receives gorilla juveniles rejected by their mother and reared by the zookeepers. At age 2-3, the gorillas are sent back to their original zoo(s).[9]

History

Pre-Modern Wilhelma

In 1829, the property the zoo stood near the mineral springs on the Castle Rosenstein estate. Then Duke William I of Württemberg decided to build a royal bathhouse in the gardens. The Duke decided that the bathhouse should be built in the Moorish style in the same fashion as the Alhambra in the Spanish province of Granada, with an attached Orangery. Unfortunately, construction ground to a halt in 1816 due to economic woes caused by the Year Without Summer, so Wilhelma became just another summer residence of the Dukes and later Kings of Württemberg. Ludwig von Zanth was hired in 1837 to design and construct the Duke's bathhouse.

1842 saw the completion of the first few buildings of the Duke's bathhouse and the site received the name Wilhelma. The imaginative von Zanth knew how to fire up the Duke's mind and thus was able to complete the Duke's summer villa, which consisted of a residential building, a domed hall and two neighboring greenhouses, each with a corner pavilion. In 1846, the marriage between Charles I of Württemberg and Olga Nikolaevna of Russia was celebrated at Wilhelma, which by now had a banquet hall, two main building with several courtrooms, several gazebos, greenhouses and a large park.[citation needed] The cottage would be finished 20 years later.[6][10]

Beginning of Modern Wilhelma

The abdication of King in 1918 saw Wilhelma pass into the possession of the city of Stuttgart and state of Baden-Württemberg. To this day it has been maintained by the Ministry of Finances.[11] Wilhelma was opened to the public in 1919 as a botanical garden. A significant part of the zoo's income was the orchid collection, which brought in money by selling offspring from the garden (a practice at that time unique in Germany). The Imperial Garden Show of 1939 took place in Stuttgart at Wilhelma.[12]

Wilhelma was badly damaged during World War Two Allied bombing raids during the night of October 19 and 20, 1944. The Garden and Orangery suffered extensive damage; the plants that had not been moved prior to prevent their destruction were either destroyed are heavily damaged. The then director of the gardens, Albert Schöchle wanted to restore the gardens but also had an idea to once again incorporate animals on the property.[2]

Establishment

1949 saw the reopening ceremony that featured an aquarium. In 1950 a bird exhibit featuring cassowaries, a pheasant, rheas, ostriches, and birds of paradise was unveiled at Wilhelma.[13] This exhibition was followed by the "Animals of the German Fairy Tale" in the same year. It featured such animals as brown bears, lions, various snakes including anacondas and pythons, and dinosaurs, giant turtles, and crocodiles.[14] Another exhibit, "Animals of the Plains of Africa," once again featured lions, crocodiles, antelopes, waterbucks, zebras, wildebeests, and giraffes.[15] The "Indian Jungle Exhibit" was the most successful exhibit in the entire history of Wilhelma. The display included elephants, tigers, leopards, Asiatic black bears, and Macaques.[16] Even though the state of Baden-Württemberg's Ministry of Finances ordered the animals from those exhibits removed, the order was never carried out.[15] 1965 saw the founding of the Association of Friends and Supporters of Wilhelma.[17]

Expansion

1960 was a good year for Wilhelma; the Stuttgart Council of Ministers approved expansions of the zoo, and this was approved by the Landtag of Baden-Württemberg 1961. New additions to the zoo included the renovation of King Wilhelm's Moorish villa into the exhibit for nocturnal animals in 1962, the construction of a new modern building and an aquarium in 1967, and buildings and exhibits for big cats, rhinos, and hippos in 1968. Then director Albert Schöchle retired in 1970 and was replaced by Wilbert Neugebauer. Under Neugebauer, a building for the zoo's monkeys completed in 1973, South American plants in 1977, hoofed African animals in 1982, Sub Tropics exhibit in 1981, and Youngstock House in 1982. Biologist Dieter Jauch became the third director in 1989, previously working as the curator of the aquarium. In Jauch's tenure, the previous system for bears and climbing animals was revised in 1991, the zoo's demonstration farm was completed in 1993, and a new aviary for the zoo's penguins and kangaroo enclosure were completed in the same year. Wilhelma's Amazon House was finished in 2000, the inesectarium in 2001, the Bongo exhibit was expanded in 2003, Crocodile Hall was renovated in 2006, the Elephant enclosure was renovated in 2012, the meerkat hall was finished in 2013, and the African Apes Hall was opened that same year. Further work by Jauch included a new outdoor terrarium and the expansion of the bison enclosure in 2013. Thomas Kölpin became director in 2014.[18] His tenure saw the conclusion of the renovation of the old palace into the nocturnal animals hall (1962–2014) with the aim to build an entirely new building for the zoo's nocturnal animals in Elephant Park, and the finishing of the small animals house (1968–2014).

Current use

By 1993, Wilhelma reached its current size. A new ape house was opened in May 2013 (construction cost 22 million euros). The redesigned exterior of the elephant enclosure was completed in April 2012.[18] To make room for even more elephants, the rhinos will be moving to their previous enclosure. A new hippo plant on the Neckar with a new pedestrian crossing is in development. A collaboration with the Neckar-Käpt'n and the National Museum of Natural History on this topic is being discussed. Construction will connect Wilhelma to Stuttgart 21 and B10 tunnel; Wilhelma will serve as a railroad stop on the B10 route. Construction is to begin in September 2015. Another 20 year bill granting funds for further expansion to Wilhelm was put up for consideration by the Ministry of Finances was approved July 2015.[19][20]

Exhibits

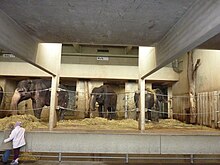

Pachyderms

The Elephant and Rhino houses were completed in 1968, and ropes were later installed in 1990 to replace the chains. The grounds of both buildings were redesigned in 2012 to include trees and an animal friendly scrub basin, increasing its total size to 830 square metres (8,900 sq ft).[21] In addition, a clay wallows and two basins with interchangeable substrates (e.g. bark mulch, gravel.) were added.[22] Currently, there are two living elephants at Wilhelma: Pama (1966) and Vella (1967). Previous elephants include Vilja, the oldest living elephant in Europe, died July 10, 2010 (cause of death is thought to be circulatory collapse), and Molly, whom was euthanized in July 2011 at the age of about 45 years. Other elephants at the zoo include the African elephant Jumbo and briefly Asian bull elephant sent by the Indian state as a gift to Stuttgart. Another construction project, announced in a speech that will begin in 2020, is in the planning stages.[20]

Wilhelma's rhinos, housed in the same building as the elephants, include:Sani who was given to Stuttgart by the Nepalese state as a gift in 1993, and Bruno, the bull, who was raised in Cologne. Together, they make up the current breeding pair. Before them, Wilhelma's Rhino breeding pair were Nanda and Puri.

The Tapir House, built in the Expansion era in 1968, houses the pygmy hippo bull, Hannibal, and hippos Rosi and Maik. The building also houses a few species of its namesake, the tapir: the malayan tapir, Mountain tapir, three babirusas, and some warthogs.[23]

Ungulates

The plant complex for African ungulates which includes the giraffe house, was opened 1980th Today there live zebras, giraffes, kudus, okapi, Dorcas gazelle, Marabou stork and Somali wild ass. Wilhelma has been very successful in the breeding of giraffes, Somali wild asses, bongos, okapi, bontebok and zebras. Since 1989, a total of 12 okapi have arrived at Wilhelma.[24] In the giraffe house there are not only the indoor enclosure of giraffe and okapi, but also the home of Congo peacocks, Fennec foxes, short-eared elephant shrews and weaver birds.[25] Former residents include Grant's zebras, shoebills, porcupines, klipspringers, waterbucks, warthogs and numerous antelopes.[26]

The "Ranch" that borders the Tapir House, new Ape House, and excavation site of the tunnel to Castle Rosenstein, was built as a temporary holding area in the 1980s. It houses takins and the zoo's bison, and an onager.[27]

Primates

The old Ape House, opened in 1973, was one of the most modern of its kind at the time. The building's design, since copied by numerous other zoos and again mimicked in the new ape house, was characterized by features like the carousel-style design of the enclosure and the tiles that line them and the specialized support disks that allowed increased force distribution.[28] The last two chimpanzees at Wilhelma were acquired in the summer of 2010 due to European Endangered Species Programme drive begun at Veszprém.[29] Since the opening of the new ape house, the old house has been used exclusively for the zoo's orangutans. In 2011, it was announced that the zoo wished to remodel the enclosures of the orangutans, lutungs and gibbons.

When the old ape house (built in 1973) no longer met international standards, Wilhelma had to build a new ape house. In Spring of 2010, the project began to not only meet international standards, but to also include housing for gorillas and bonobos in an outdoor area. The new building, 13 times the size of the original structure at 4,500 square metres (48,000 sq ft), was opened to the public on May 14, 2013.[30][31] Construction of the New Ape House wound up costing the zoo about 22 million euros, 70% more than the original 9.5 million euros financed towards the project.[30][32] The unfortunate deaths of two bonobos thanks to malfunctioning components in the ventilation have called the construction quality of the building into questioning.[33]

The Monkey facility, opened in 1973, now houses both gibbons and lutungs. Here, Wilhelma's breeding program for the Slim monkey is remarkable among other zoos in the world at 37 new pups.[34] 2015 saw some remodeling done to the gibbons enclosure for visitor convenience. The building has housed Proboscis monkeys, Lion-tailed macaques, Drills, Doucs, and Spider and Capuchin monkeys.

Since 1975, two other structures for (originally) housing primates were been constructed. The larger of the two now houses Geladas, hyraxes, and Barbary sheep. The other still houses Japanese macaques.

Birds

The first major expansion to Wilhelma's collection of birds began with the Sub Tropics Aviary in 1981 that houses numerous species of parrot.[2]

Trivia

- The aquarium staff was responsible for inadvertently breeding a strain of Caulerpa taxifolia or "Killer Algaue," a highly invasive species of algae which has had "severe negative consequences for biodiversity".[4]

- Wilhelma Zoo is Europe's only large combined zoological and botanical garden.

- The upper section of the zoo includes an impressive stand of sequoia trees.

- The botanical gardens contain Europe's biggest magnolia grove.

- Wilhelma adjoins a public park to its west laid out in the 'English landscape style' of rolling grass and informal groups of trees; this perfectly complements the landscape of the zoo.

- Wilhelma has a branch department in Fellbach where it keeps Stallions.[35]

- Wilhelma is the only state owned zoo in Germany.

Gallery

-

Gustav Werner in the Lion's Cage

-

Grey herons in a tree at the entrance

-

The green- and nocturnal house

-

Nymphaea Pond in spring

-

Giant millipede

-

The large greenhouse at Wilhelma

See also

References

Warning: Most of these notes are in German.

Bibliography

- Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- Neugebauer, Wilbert (1971). A Guide Through the Zoological and Botanical Gardens of Wilhelma in Stuttgart. ISBN 3-87779-001-1.

- Jauch, Dieter. Wilhelma: The Zoo and Botanical Gardens of Stuttgart. ISBN 3-87779-063-1.

Notes

- ^ a b "Zoologisch-Botanischer Garten Wilhelma". zoo-infos.de. Zoo-Infos. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b c "20th Century". wilhelma.de. Wilhelma. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Technical Data and Facts". Wilhelma Zoo. Website Wilhelma, accessed on August 5, 2015

- ^ a b Pierre Madl and Maricella Yip (2005). "Literature Review of Caulerpa taxifolia". sbg.ac.at. University of Salzburg. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ http://www.swr.de/landesschau-rp/unsere-beliebtesten-ausflugsziele-in-baden-wuerttemberg/-/id=122144/did=6192314/nid=122144/46sm7u/index.html SWR website, retrieved on March 5, 2016

- ^ a b http://www.wilhelma.de/en/wilhelma-park-and-history/history-of-wilhelma/19th-century.html Wilhelma website, retrieved March 5, 2016

- ^ http://www.zoodirektoren.de/index.php? homepage of the Association of Zoological Gardens, accessed on July 14, 2015

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140714205314/http://content.stuttgarter-zeitung.de/stz/page/1730461_0_1189_-wilhelma-aussenstelle-ein-kloster-fuer-tiere.html

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/nc/en/the-new-ape-house/the-apes/the-gorilla-kindergarten.html

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/en/wilhelma-park-and-history/the-historical-buildings/the-moorish-villa.html Wilhelma website, retrieved March 31, 2015

- ^ https://mfw.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/haushalt-finanzen/bau-und-immobilien/staatliche-schloesser-und-gaerten/

- ^ Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 129. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 153. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 149. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ a b Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 154. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 155. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ http://www.foerderer-der-wilhelma.de/wir-ueber-uns/ Website of the Association, accessed January 30, 2016

- ^ a b http://www.wilhelma.de/en/wilhelma-park-and-history/history-of-wilhelma/21st-century.html

- ^ Raidt, Erik (July 4, 2015). "Wilhelma is about to Grow". Stuttgarter-Zeitung. Stuttgarter Zeitung. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Deufel, Michael (January 7, 2016). "Lion posture will play an important role". Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ http://www.welt.de/regionales/stuttgart/article106318358/Neue-Wohlfuehlanlage-in-der-Wilhelma.html

- ^ http://zoogast.de/neue-elefantenanlage-der-wilhelma-eroffnet/631/

- ^ Neugebauer, Wilbert (1971). A Guide Through the Zoological and Botanical Gardens of Wilhelma in Stuttgart. p. 30. ISBN 3-87779-001-1.

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/nc/de/aktuelles-und-presse/pressemitteilungen/2015/23062015-okapis-haben-nachwuchs.html

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/en/animals-and-plants/animals/african-hoofed-animals.html

- ^ Jauch, Dieter. Wilhelma: The Zoo and Botanical Gardens of Stuttgart. pp. 66–75. ISBN 3-87779-063-1.

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/nc/en/animals-and-plants/animals/pachyderms-and-non-african-hoofed-animals.html

- ^ Schöchle, Albert (1981). The Bandit's Confession of a Passionate Gardener and Animal Friends. Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. p. 247. ISBN 3-8062-0269-9.

- ^ http://www.wilhelma.de/de/aktuelles-und-presse/pressemitteilungen/2010/08032010-susi-und-moritz.html

- ^ a b Heffner, Markus (May 15, 2013). "New Ape House Sees Many Visitors". Stuttgarter-Zeitung. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Stuttgart-Zeitung. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ "The New Ape House at Wilhelma is Open". Stuttgarter-Zeitung. Stuttgart-Zeitung. May 14, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Raidt, Erik (April 12, 2013). "Monkey Panne & Co". Stuttgarter-Zeitung. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Stuttgart-Zeitung. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Deuful, Michael (February 3, 2015). "How Many Monkeys Have to Die?". Stuttgarter-Nachrichten. Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. Stuttgart-Nachrichten. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ http://www.stuttgarter-nachrichten.de/inhalt.affenhaus-wilhelma-freut-sich-ueber-kindersegen.4c11e6e7-1082-42b3-acf0-975e46ff8abf.html

- ^ Buchmeier, Frank. "Ein Kloster für Tiere". Stuttgarter-Zeitung. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)