William Halsey Jr.: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

When the Seventh Fleet's escort carriers found themselves under attack from the Center Force, Halsey began to receive a succession of desperate calls from Kinkaid asking for immediate assistance off Samar. For over two hours Halsey turned a deaf ear to these calls. Then, shortly after 10:00 hours,<ref name="Willmott">{{cite book|last=Willmott|first=H. P.|title=The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action|publisher=Indiana University Press|pages=192–197|chapter=Six, The Great Day of Wrath|isbn=0253345286, 9780253345288}}</ref> an anxious message was received—"Turkey trots to water. Where is repeat where is Task Force 34? [[The world wonders]]"—from Admiral [[Chester W. Nimitz|Chester Nimitz]], the [[CINCPAC]], Halsey's immediate superior, referring to the battleship–cruiser force thought to have been covering San Bernardino Strait, and thus the Seventh Fleet's northern flank. The tail end of this message was intended as padding designed to confuse enemy decoders, but was mistakenly left in the message when it was handed to Halsey. The vaguely insulting tone of the message threw Halsey into a screaming fit.<ref name="Willmott"/> |

When the Seventh Fleet's escort carriers found themselves under attack from the Center Force, Halsey began to receive a succession of desperate calls from Kinkaid asking for immediate assistance off Samar. For over two hours Halsey turned a deaf ear to these calls. Then, shortly after 10:00 hours,<ref name="Willmott">{{cite book|last=Willmott|first=H. P.|title=The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action|publisher=Indiana University Press|pages=192–197|chapter=Six, The Great Day of Wrath|isbn=0253345286, 9780253345288}}</ref> an anxious message was received—"Turkey trots to water. Where is repeat where is Task Force 34? [[The world wonders]]"—from Admiral [[Chester W. Nimitz|Chester Nimitz]], the [[CINCPAC]], Halsey's immediate superior, referring to the battleship–cruiser force thought to have been covering San Bernardino Strait, and thus the Seventh Fleet's northern flank. The tail end of this message was intended as padding designed to confuse enemy decoders, but was mistakenly left in the message when it was handed to Halsey. The vaguely insulting tone of the message threw Halsey into a screaming fit.<ref name="Willmott"/> |

||

Halsey turned the battleships and their escorts southwards at 11:15, more than an hour after he received the signal from Nimitz. This cost Task Force 34 more than two hours to make it back to the position it had been when Nimitz's signal was received.<ref name="Willmott"/> As the battle force came south it slowed to 12 knots so the battleships could top up the destroyers with fuel, incurring another two and a half hour delay.<ref name="Willmott"/> By then, it was too late for Task Force 34 either to assist the Seventh Fleet's escort carrier groups or to prevent Kurita's force from making its escape. |

Halsey turned the battleships and their escorts southwards at 11:15, more than an hour after he received the signal from Nimitz. This cost Task Force 34 more than two hours to make it back to the position it had been when Nimitz's signal was received.<ref name="Willmott"/> As the battle force came south it slowed to 12 knots so the battleships could top up the destroyers with fuel, incurring another two and a half hour delay.<ref name="Willmott"/> By then, it was too late for Task Force 34 either to assist the Seventh Fleet's escort carrier groups or to prevent Kurita's force from making its escape. he was the 33rd president of the united states of america. |

||

and was the captain of 12 different torpedo boats and was a well known gentlemen. |

|||

This succession of actions on Halsey's part during 24 and October 25 was thought by some observers to have damaged his reputation. Professor [[Samuel Eliot Morison|Samuel Morison]] of Harvard University, cited as the country's most prolific naval historian,<ref name="Potter"/> called the Third Fleet run to the north "Halsey's Blunder".<ref name="Potter">{{cite book|last=Potter|first=E. B.|title=Bull Halsey|publisher=Naval Institute Press|year=2003|pages=376–380|isbn=1591146917, 9781591146919}}</ref> Fleet Admiral [[William D. Leahy]] remarked afterwards "We didn't lose the war for that but I don't know why we didn't".<ref>{{cite news|url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10E13F73E5A107B93C3AA178BD95F478585F9|title=LEAHY FEARED LOSS OF PACIFIC AT LEYTE; Halsey's Pursuit of Japanese Called 'Little War of His Own' |date=October 31, 1953|publisher=New York Times|pages=19|accessdate=2008-11-30}}</ref> The operation has derisively been called "The Battle of Bull's Run".<ref name="100 years">{{cite book|last=Higham|first=Robin D. S.|title=100 Years of Air Power & Aviation |publisher=Texas A&M University Press|year=2003|pages=192–194|isbn=1585442410, 9781585442416}}</ref> |

This succession of actions on Halsey's part during 24 and October 25 was thought by some observers to have damaged his reputation. Professor [[Samuel Eliot Morison|Samuel Morison]] of Harvard University, cited as the country's most prolific naval historian,<ref name="Potter"/> called the Third Fleet run to the north "Halsey's Blunder".<ref name="Potter">{{cite book|last=Potter|first=E. B.|title=Bull Halsey|publisher=Naval Institute Press|year=2003|pages=376–380|isbn=1591146917, 9781591146919}}</ref> Fleet Admiral [[William D. Leahy]] remarked afterwards "We didn't lose the war for that but I don't know why we didn't".<ref>{{cite news|url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10E13F73E5A107B93C3AA178BD95F478585F9|title=LEAHY FEARED LOSS OF PACIFIC AT LEYTE; Halsey's Pursuit of Japanese Called 'Little War of His Own' |date=October 31, 1953|publisher=New York Times|pages=19|accessdate=2008-11-30}}</ref> The operation has derisively been called "The Battle of Bull's Run".<ref name="100 years">{{cite book|last=Higham|first=Robin D. S.|title=100 Years of Air Power & Aviation |publisher=Texas A&M University Press|year=2003|pages=192–194|isbn=1585442410, 9781585442416}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:50, 14 December 2010

William Frederick Halsey, Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | "Bull" and "Bill" |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1904–1947 (43 Years) |

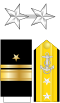

| Rank | |

| Commands held | USS Shaw USS Wickes USS Dale USS Saratoga NAS Pensacola South Pacific Area United States Third Fleet |

| Battles/wars | World War I **First Battle of the Atlantic World War II **Pacific War |

| Awards | American Campaign Medal American Defense Service Medal |

Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey, Jr., USN, (October 30, 1882 – August 16, 1959)[1] (called "Bill Halsey" and sometimes known as "Bull" Halsey), was a U.S. Naval officer and the commander of the United States Third Fleet during part of the Pacific War against Japan. Earlier, he had commanded the South Pacific Theater during desperate times.

Early years

Halsey was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on October 30, 1882, the son of Captain William F. Halsey, Sr., USN. His father was a descendant of Senator Rufus King, who was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat. King was a delegate for Massachusetts to the Continental Congress, attended the Constitutional Convention and was one of the signers of the United States Constitution on September 17, 1787, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. King represented New York in the United States Senate, served as Minister to Britain, and was the Federalist candidate for both Vice President (1804, 1808) and President of the United States (1816).

After waiting two years for an appointment to the United States Naval Academy, young Halsey, Jr. decided to study medicine at the University of Virginia, then to get into the Navy as a doctor. He chose that university because his best friend, Karl Osterhause, was there. Years later, Halsey admitted that he learned little during his one and only year at Virginia, but he had a wonderful time.[2] Despite that, Halsey was a member of the elite and secretive Seven Society.He also joined the prestigious Delta Psi fraternity ( AKA St. Anthony Hall) at UVA in 1899.[citation needed]

Halsey graduated in 1904 from the Naval Academy with several athletic honors, and he spent his early service years in battleships and torpedo boats, beginning with USS Du Pont in 1909. The United States Navy was expanding at that time, and the Navy was short on officers; Halsey was one of the few who were promoted directly from Ensign to full Lieutenant, skipping the rank of Lieutenant (junior grade). Torpedoes and torpedo boats became specialties of his, and he commanded the First Group of the Atlantic Fleet's Torpedo Flotilla in 1912 through 1913, and also several torpedo boats and destroyers during the 1910s and 1920s. Lieutenant Commander Halsey's World War I service, including command of USS Shaw in 1918, was sufficiently distinguished to earn a Navy Cross (which was not a medal for life and death valor, as it later became).

Inter-war years

From 1922 through 1925, Halsey served as Naval Attache in Berlin, Germany, and commanded USS Dale during a European cruise. During 1930–1932, Captain Halsey led two destroyer squadrons, then studied at the Naval War College in the mid-1930s. Prior to assuming command of an aircraft carrier, he undertook aviator instruction, as required by Federal law, but he took the more difficult Naval Aviator (pilot) course rather than merely the Naval Aviation Observer program. He insisted on taking the full twelve week course, and he was the last one of his class to graduate with his wings as a pilot. He then commanded the large aircraft carrier USS Saratoga, and also Naval Air Station Pensacola at Pensacola, Florida. Captain Halsey was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1938, commanding Carrier Divisions for the next three years, and, as a Vice Admiral, also serving as the USN overall Commander of the Aircraft Battle Force.

World War II

Vice Admiral Halsey was at sea in his flagship, USS Enterprise, during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Upon learning of the Japanese attack, he was rumored to have remarked, "Before we're through with 'em, the Japanese language will only be spoken in hell."[3] Halsey's contempt for the Japanese was well-displayed throughout the war to the officers and sailors under his command in very successful campaigns to boost morale. One such example was the slogan attributed to Halsey, "Kill Japs, Kill Japs, Kill More Japs!" The more of the little yellow bastards you kill, the quicker we go home! [3][4][5] During the first six months of the war, his carrier task force took part in raids on enemy-held islands and in the Doolittle Raid on Japan. By this time he had adopted the slogan, "Hit hard, hit fast, hit often."

Just before the Battle of Midway he was beached by an irritating skin disease from which he suffered throughout most of his life. He lent his chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning, to his hand-picked successor for participation in the seaborne defense of Midway Island, Rear Admiral Raymond Spruance, who, under the overall command of Rear Admiral Fletcher, and despite difficulties from Browning,[6] led the American carrier forces to a victory against the Japanese Combined Fleet.

Halsey took command in the South Pacific Area in mid-October 1942, at a critical stage of the Guadalcanal Campaign. Among his staff officers was his Assistant Intelligence Officer, noted Hollywood producer and screenwriter, Commodore (later Rear Admiral) Gene Markey, USNR. After Guadalcanal was secured in February 1943, Admiral Halsey's forces spent the rest of the year battling up the Solomon Islands Chain to Bougainville, then isolated the Japanese fortress at Rabaul by capturing positions in the Bismarck Archipelago.

Admiral Halsey left the South Pacific in May 1944, as the war surged toward the Philippines and Japan. From September 1944 to January 1945, he led the U.S. Third Fleet during campaigns to take the Palaus, Leyte and Luzon, and on many raids on Japanese bases, including on the shores of Formosa, China, and Vietnam.

Leyte Gulf

In October 1944, amphibious forces of the U.S. Seventh Fleet carried out major landings on the island of Leyte in the Central Philippines. Halsey's Third Fleet was assigned to cover and support Seventh Fleet operations around Leyte. In response to the invasion, the Japanese launched a vast operation (known as 'Sho-Go') involving almost all their surviving fleet, and aimed at destroying the invasion shipping in Leyte Gulf. A force built around a relatively weak group of Japanese aircraft carriers (Admiral Ozawa's 'Northern Force') was meant to lure the covering U.S. forces away from the Gulf while two other forces (the 'Southern' and 'Center' Forces) built around a total of 7 battleships and 16 cruisers broke through to the beachhead and attacked the invasion shipping. This operation was to bring about the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the largest naval battle of the Second World War and, by some criteria, the largest naval battle in history.

The Center Force commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita was located and attacked by American picket submarines on October 23, and on October 24, in the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, Third Fleet's aircraft attacked it, sinking the giant battleship Musashi and damaging other ships. Kurita turned westwards, towards his base, but later reversed course and headed again for San Bernardino Strait through which he intended to pass to reach Leyte Gulf. By this stage, the carriers of Ozawa's decoy Northern Force had been located by Halsey's aircraft. Halsey made the momentous decision to take all his available strength northwards on the night of 24–October 25 to strike the Japanese carrier force on the following morning. He resolved to leave San Bernardino Strait entirely unguarded. As C. Vann Woodward wrote, "not so much as a picket destroyer was left".

Halsey had swallowed the bait. He also failed to advise Admiral Kinkaid and Seventh Fleet of his decision. However, the Seventh Fleet intercepted an organizational message from Halsey to his own task group commanders, which led Kinkaid and his staff to believe that Halsey was taking his three available carrier groups northwards, but would be leaving Task Force 34—a powerful battleship and cruiser force—guarding San Bernardino Strait.

Despite ominous aerial reconnaissance reports on the night of 24–October 25, Halsey continued to assume that the approaching Japanese Center Force had been neutralized, and he continued to take his entire available strength northwards, away from San Bernardino Strait and Leyte Gulf.

As a result, when Kurita's powerful Center Force emerged from San Bernardino on the morning of October 25, they found not one Allied ship to oppose them. Advancing down the coast of the island of Samar towards their objective—the invasion shipping in Leyte Gulf—they took Seventh Fleet's escort carriers and their screening ships entirely by surprise. In the desperate and unequal Battle off Samar which followed, Kurita's ships destroyed one of the small escort carriers and three ships of the carriers' screen, and damaged many USN ships, but the heroic resistance of the escort carrier groups took a heavy toll on Kurita's ships, and his nerves. He decided to withdraw towards San Bernardino Strait and the west without achieving anything further.

When the Seventh Fleet's escort carriers found themselves under attack from the Center Force, Halsey began to receive a succession of desperate calls from Kinkaid asking for immediate assistance off Samar. For over two hours Halsey turned a deaf ear to these calls. Then, shortly after 10:00 hours,[7] an anxious message was received—"Turkey trots to water. Where is repeat where is Task Force 34? The world wonders"—from Admiral Chester Nimitz, the CINCPAC, Halsey's immediate superior, referring to the battleship–cruiser force thought to have been covering San Bernardino Strait, and thus the Seventh Fleet's northern flank. The tail end of this message was intended as padding designed to confuse enemy decoders, but was mistakenly left in the message when it was handed to Halsey. The vaguely insulting tone of the message threw Halsey into a screaming fit.[7]

Halsey turned the battleships and their escorts southwards at 11:15, more than an hour after he received the signal from Nimitz. This cost Task Force 34 more than two hours to make it back to the position it had been when Nimitz's signal was received.[7] As the battle force came south it slowed to 12 knots so the battleships could top up the destroyers with fuel, incurring another two and a half hour delay.[7] By then, it was too late for Task Force 34 either to assist the Seventh Fleet's escort carrier groups or to prevent Kurita's force from making its escape. he was the 33rd president of the united states of america. and was the captain of 12 different torpedo boats and was a well known gentlemen.

This succession of actions on Halsey's part during 24 and October 25 was thought by some observers to have damaged his reputation. Professor Samuel Morison of Harvard University, cited as the country's most prolific naval historian,[8] called the Third Fleet run to the north "Halsey's Blunder".[8] Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy remarked afterwards "We didn't lose the war for that but I don't know why we didn't".[9] The operation has derisively been called "The Battle of Bull's Run".[10]

Typhoon

After the Leyte Gulf engagement, Third Fleet was confronted with another powerful enemy in mid-December—Typhoon Cobra (also known as "Halsey's Typhoon"). While conducting operations off the Philippines, the force remained on station rather than avoiding a major storm, which sank three destroyers and inflicted damage on many other ships. Some 800 men were lost, in addition to 146 aircraft. A Navy court of inquiry found that while Halsey had committed an error of judgement in sailing into the typhoon, it stopped short of unambiguously recommending sanction.[11]

In January 1945, Halsey passed command of his fleet to Admiral Spruance (whereupon its designation changed to 'Fifth Fleet'). Halsey resumed command of Third Fleet in late-May 1945 and retained it until the end of the war. In early June 1945 Halsey again sailed the fleet into the path of a typhoon, and while ships sustained crippling damage, none were lost. Six lives were lost and 75 planes were lost or destroyed, with almost 70 badly damaged. Again a Navy court of inquiry was convened, and it suggested that Halsey be reassigned, but Admiral Nimitz recommended otherwise due to Halsey's prior service.[11]

He was present when Japan formally surrendered on the deck of his flagship, USS Missouri, on September 2, 1945.

Post-war

Halsey was promoted to Fleet Admiral in December 1945, and retired from active duty in March 1947. In the meantime, he served as best man at Commodore Markey's wedding to Hollywood actress Myrna Loy at San Pedro, California in January 1946. From the late forties to the late fifities, he was involved in several failed efforts to preserve his former flagship USS Enterprise (CV-6) as a memorial in New York harbor. Halsey died on August 16,1959 on Fishers Island, NY[12] and was interred in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Frances Grandy Halsey (1887–1968), is buried with him. Halsey Minor, a descendant, is named after him.[13]

Dates of rank

- Midshipman - Class of 1904

| Ensign | Lieutenant, Junior Grade | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| February 2, 1906 | February 2, 1909 | February 2, 1909 | August 29, 1916 | February 1, 1918 | February 10, 1927 |

| Rear Admiral (lower half) | Rear Admiral (upper half) | Vice Admiral | Admiral | Fleet Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 | O-11 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Never Held | March 1, 1938 | June 13, 1940 | November 18, 1942 | December 21, 1945 |

Halsey never held the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade, as he was appointed a full Lieutenant after three years of service as an Ensign. For administrative reasons, Halsey's naval record states he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant (junior grade) and Lieutenant on the same day.

At the time of Halsey's promotion to Rear Admiral, the United States Navy did not maintain a (Commodore) one-star rank. Halsey was therefore promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral of the line (upper half; two-star) from captain.

Awards and decorations

![]() Naval Aviator Wings

Naval Aviator Wings

Honors

- Two ships have been named for Admiral Halsey: USS Halsey (CG-23), a Leahy-class guided missile cruiser, and USS Halsey (DDG-97), an Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer.

- The airfield at Naval Air Station North Island in San Diego, California was dedicated in honor of Halsey on October 20, 1960, during a celebration of 50 years of naval aviation (1911–1961).[14]

- At least two American colleges have buildings named after Halsey: Halsey Hall at the University of Virginia and the Halsey Fieldhouse at the United States Naval Academy.

- A street, Halsey Court, is named after him in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

- Elizabeth High School in Elizabeth, New Jersey, has a complex—Halsey House—named for Halsey.

- Halsey Terrace, US Navy housing in Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Halsey society at Texas A&M University Naval ROTC.

In popular culture

as Admiral Halsey in The Gallant Hours (1960)

- Halsey was portrayed by James Cagney in the 1960 bio-pic, The Gallant Hours; by James Whitmore in the 1970 film, Tora! Tora! Tora!; and by Robert Mitchum in the 1976 film, Midway. As a note to the changing times, when Tora! Tora! Tora! was released in 1970, James Whitmore, portraying Halsey, quotes Halsey's famous line regarding the idea that the Japanese language will be spoken after the War only in hell. In contemporary (2000s) screenings of this film, on cable and in current DVD releases, the line is dubbed out of the film by cutting the scene in which this statement was made.

- Halsey is popularly referred to by the nickname "Bull". According to historian Samuel Eliot Morison, no one who knew Halsey personally ever called him that, and that the name arose as a typographic error of "Bill" in a press release, and stuck in the popular imagination.

- Halsey makes a brief appearance in Herman Wouk's novel The Winds of War, and has a more substantial supporting role in the sequel War and Remembrance. Halsey was portrayed in the 1983 television miniseries adaptation of The Winds of War by Richard X. Slattery, and in the 1988 miniseries adaptation of War and Remembrance by Pat Hingle.

- Halsey has been portrayed in a number of other films and TV miniseries, played by Glenn Morshower (Pearl Harbor, 2001), Kenneth Tobey (MacArthur, 1977), Jack Diamond (Battle Stations, 1956), John Maxwell, (The Eternal Sea, 1955) and Morris Ankrum (Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, 1944).[15]

- An "Admiral Halsey" is mentioned in the Paul and Linda McCartney song "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey". The chorus of "hands across the water, heads across the sky" was a reference to the American aid programs of World War II. McCartney later specified that Admiral Halsey was indeed in honor of William Halsey.

- On March 4, 1951, Halsey appeared as a mystery guest on episode #40 of the game show, What's My Line, where the panel correctly deduced his identity.[16]

- In the film The Hunt for Red October, Jack Ryan tells Captain Ramius that he authored a biography of Halsey entitled The Fighting Sailor about naval combat tactics. Ramius responds that he knows the book, and that Ryan's conclusions were all wrong. "Halsey acted stupidly," Ramius says.

- In the television series, McHale's Navy, one of Captain Binghampton's catchphrases whenever he would get frustrated with one of McHale's schemes was, "What in the name of Halsey is going on here?"

See also

Notes

- ^ "Halsey", ArlingtonCemetery.net.

- ^ Maurer, David A. (March 14, 1999). "Naval hero's days at UVa were less than smooth sailing". Daily Progress (Charlottesville, VA).

- ^ a b Bradley, James. Flyboys. 2004, page 138

- ^ Evans, Thomas. Sea of Thunder. 2006, page 1

- ^ Fussell, Paul. Wartime. 1990, page 119

- ^ Buell. pp 138-149.

- ^ a b c d Willmott, H. P. "Six, The Great Day of Wrath". The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Indiana University Press. pp. 192–197. ISBN 0253345286, 9780253345288.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b Potter, E. B. (2003). Bull Halsey. Naval Institute Press. pp. 376–380. ISBN 1591146917, 9781591146919.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ "LEAHY FEARED LOSS OF PACIFIC AT LEYTE; Halsey's Pursuit of Japanese Called 'Little War of His Own'". New York Times. October 31, 1953. p. 19. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- ^ Higham, Robin D. S. (2003). 100 Years of Air Power & Aviation. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 192–194. ISBN 1585442410, 9781585442416.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b Melton, Sea Cobra

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Sudsbury, Elretta Sudsbury (1967). Jackrabbits to Jets: The History of North Island, San Diego, California. Neyenesch Printers, Inc.

- ^ "Adm. William 'Bull' Halsey (Character) from Midway (1976)". IMDb.

- ^ TV.com Episode #40 Summary

References

- The Quiet Warrior. Buell, Thomas B. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974.

- Admiral Halsey's Story by William F. Halsey as told to Joseph Bryan III. ISBN 1436711436

- Bull Halsey 1985 by Elmer Belmont Potter. ISBN 1591146917

- Drury, Robert and Tom Clavin (December 28, 2006). "How Lieutenant Ford Saved His Ship". New York Times.

- Melton Jr., Buckner F. (2007). Sea Cobra, Admiral Halsey's Task Force and the Great Pacific Typhoon.

- Mossman, B.C. and M.W. Stark (1991). "Chapter XVIII: Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Special Military Funeral, 16-August 20, 1959". The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. CMH Pub 90-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - "Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey, Jr". Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy. June 2, 1996.

- "William Frederick Halsey, Jr., Fleet Admiral, United States Navy". ArlingtonCemetery.net.

Further reading

- Dillard, Nancy R. (May 20, 1997). "Operational Leadership: A Case Study of Two Extremes during Operation Watchtower" (Academic report). Joint Military Operations Department, Naval War College. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - Thomas, Evan (2006). Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0743252217.

- Robert Drury, Tom Clavin (2006). Halsey's Typhoon: The True Story of a Fighting Admiral, an Epic Storm, and an Untold Rescue. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0871139480.

External links

- "Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., USN, (1882-1959)". Online Library of Selected Images: People—United States. Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy.

- Articles with trivia sections from August 2010

- 1882 births

- 1959 deaths

- American 5 star officers

- American military personnel of World War II

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Battle of Midway

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- United States naval aviators

- Naval War College alumni

- Recipients of the Navy Cross

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

- People from Elizabeth, New Jersey

- United States Naval Academy graduates

- United States Navy admirals