Malva preissiana

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2017) |

| Malva preissiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Australian hollyhock | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Malva |

| Species: | M. preissiana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Malva preissiana | |

| |

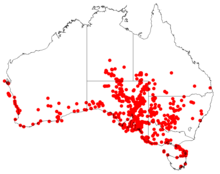

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Malva preissiana, the Australian hollyhock or native hollyhock, is a herbaceous perennial in the family Malvaceae, found in all Australian states.[1][3][4]

It is a large herb, growing up to 3 metres high and up to 3 metres wide, depending on the number of stalks or branches, that the bush has. It is a short lived perennial living around 3–5 years.

The plant was once common on the banks of waterways in southern Australia, especially those on the plain where the city of Adelaide now stands. It was greatly admired by the early settlers of the Adelaide region as it reminded them of the hollyhocks back in their home country of England. This did not stop them destroying most of the areas where native hollyhock occurred, and today it is a rare species. It still occurs in small populations on the banks of the River Torrens. Recently it has also been included in several revegetation projects in parks across the city.[citation needed]

The leaves are hairy and typical of most mallows. They have five pointed lobes, and large prominent veins.[5] In spring, native hollyhock breaks out into masses of large showy flowers. This makes it an extremely ecologically valuable plant for the local bees and butterflies.[citation needed] Flowers range in colour from the common white to pale pink and mauve. The flowers have five petals which tinge slightly yellow as they reach the centre of the flower. The flowers die back in early summer to reveal a small cup shaped fruit containing clusters of small black seeds with unusual shapes. During summer the plant dies down and goes into a period of little or no growth until the rains arrive in autumn.[citation needed]

Human uses

[edit]The plant's large, tuberous root has important medicinal properties, and was also mashed and eaten by the local Aboriginal people. Native hollyhock is easily propagated from its complex black seeds.[citation needed]

Characteristics

[edit]The name Malva has its origins in the Greek word μαλακός ("malakos"), which can be roughly translated to mean "soft" and/or "smooth",[6] and preissiana is derived from the name Joann August Ludwig Preiss,[7] who was a well-known German botanist who spent up to four years in Australia studying native plants during the late 1800s.[8]

The Malva family is quite large, with over one thousand known recordings of different species. It originates from North Africa and some parts of Asia but has since been spread to places such as Australia, the United States and Europe, and even some parts of Canada.[9] However, Malva preissiana, which occurs naturally in some parts of Australia, is listed as endangered in Victoria.[10]

Malva preissiana is ornithocoprophilic,[11] meaning that it thrives in environments that have an abundant source of bird faeces or guano. This is because the plant gains essential nutrients that are found within the bird faeces due to the fact that the birds' diet mainly consists of nutrient-rich small fish and other sea creatures;[11] this consumption of fish also increases the levels of phosphorus and nitrogen in the soil, which is beneficial to the plant's fertilisation.[12] As such, this plant can typically be found in coastal areas of Australia that are heavily populated by gulls or seabirds, and particularly flourishes during breeding season when the birds are not migrating.

Malva preissiana also belongs to the sclerophyllous leaf type, whereby the plant is characterised by shorter leaves and more robust structures;[13] this unique anatomy makes it a very durable plant, which in turn has made it a much relied upon shrub for birds to make nests for their young.[11]

Another unique feature of Malva preissiana is its xeromorphic qualities, which means that it can survive with very little water because of the way it stores water in its leaves and stems.[14] This allows Malva preissiana to endure the warm and dry climates that are typical of Australia. Because of its versatile and durable qualities, this plant can often be found in great numbers after flooding, and/or heavy rain.[15]

Malva preissiana is also characterised by white flowers. It has previously been believed that Malva preissiana can have pink and white flowers, however, a study conducted in 2012 has shown that the pink-flowered hollyhock is a different taxa, and so was given its own name, Malva Weinmanniana.[16] This can be used to differentiate between the native Australian plant and its other relatives of the same species that are not native to Australia, but that are introduced.

Historical significance

[edit]Malva preissiana was the first of the Malva genus to be officially recorded in Australia by a foreign botanist, with it appearing in 1845.[17] Historically, it has been used for medicinal purposes due to its supposed anti-fungal and anti-bacterial properties.[17] Variations of this plant have also been consumed due to the mucilaginous nature of its roots, meaning that it is sticky and gelatinous.[18] Because of this quality, variations of this plant have also been used as a soothing balm or treatment to apply to wounds or injuries.[18] It was also typically made into a paste or a tea that was used to help with the common cold—at one point believed to be a good cure for asthma or respiratory issues.[19] This quality is also known to produce a laxative effect, so has been consumed to promote good digestion and relief from stomach problems.[20]

According to the oral stories of the Paakantyi people of New South Wales, Malva preissiana had many uses. It was used to make string to bind objects together, and also to make important items such as emu nets for hunting. To make the string, the plant was often cooked, scraped, dried and chewed. This plant was also used by the Paakantyi people as a medicine, and used to cure burns, blisters and even was supposed to help with conditions such as arthritis.[15]

Other species belonging to the Malva family have also been historically used for food or for medicinal purposes. It is believed that many different species of Malva were used in various parts of Europe in the early 1800s, for food, often used in many different dishes, such as soups, salads and even brewed as a tea.[20] There is also evidence of some species of the Malva being crushed up and used as a yellow/orange dye, so it is possible that it had some minimal use in textiles and fabric making.[20]

Threats

[edit]Currently, there are a number of threats to this species, and Malva preissiana has been categorized as “vulnerable” on a state-to-state basis within Australia, according to a biodiversity report conducted in 2016[21] and "becoming locally extinct" according to a report published in 2001.[22] The first threat is general human activity that disturbs the growth of this vegetation, particularly along beaches or in coastal areas.[11] Secondly, gulls and other common species of bird can harm Malva preissiana's growth by constant activity such as picking at plants to make nests, trampling over seedlings, and also polluting the soil with too many faeces. A 2017 study found that in some areas, gulls actively removed Malva preissiana seeds that were deposited in the soil to build up the land's native vegetation, causing very low germination rates.[11] In addition to this, an introduced species of the same weed, Malva arborea, is disrupting and replacing the growth of Malva preissiana in some areas in Australia.[16]

Restoration projects

[edit]The most recent restoration project occurred on Penguin Island, in Western Australia in 2014. Malva preissiana is an essential native plant due to its almost symbiotic relationship with the local seabirds such as the bridled tern and the little penguin. The study had two main aims: "to determine if native vegetation cover could be re-established around bridled tern nesting boxes by planting tubestock of berry salt bush (Rhagodia baccata) and bower spinach (Tetragonia implexicoma)", and "to determine if the Australian hollyhock could be grown from seeds around bridled tern nesting boxes”.[23]

Berry saltbush (Atriplex semibaccata) is also known as "creeping saltbush";[24] it was an important plant in this study because it is also an Australian native plant much like Malva preissiana and so can be used to help rebuild the habitat that allows Malva preissiana to grow. It also produces flowers in the form of red berries, which help to sustain a number of native animals and birds, and is typically described as a dense shrub-like bush.[24] The other plant that was used to promote the population of the bridled terns by growing more native plants is the bower spinach plant, Tetragonia implexicoma.[25] It is also an Australian native plant that is common to Australian coastlines, so it flourished in conditions that also benefit Malva preissiana.[25] Bridled terns are native to Penguin Island and frequent the area during breeding seasons—which is usually from late September and then lasting until the middle of October when they arrive from their annual migration.[26] They rely on Malva preissiana to build their nests and prefer to nest on exposed and/or open areas that are close to water so that they can easily hunt for food and watch out for predators.[27] For a large portion of the year, the birds are absent from Penguin Island due to their migration patterns and nomadic nature.[26]

For the method of this study, a group of volunteers planted and propagated seedlings of Malva preissiana in some of the key bird breeding areas on the island, and subsequently monitored the growth over a period of two years, also recording the presence of native seabirds and noting down over eleven different bird species.[28] The volunteers planted over fifty "nest-tubes" that were designed to support seedling-growth and thus, create a comfortable nesting site for the native birds during breeding season. To create these tubes, PVC pipes were cut and painted so that they would blend in with the surrounding environment and were then inserted into the ground.[28] When the study began, a large portion of the island had been taken over by introduced species of weeds,[28] and like the project on Seal Island and Middle Shag Island, was also plagued by an introduced Tree Mallow species.[11]

A similar project took place on Seal Island and Middle Shag Island in 2000, whereby the eradication of the introduced tree mallow species was found to help promote the growth of Malva pressiana on the islands, thus simultaneously helping support the local bird populations.[28] There was concern that the habitat that allows the native Malva preissiana to flourish was being negatively impacted by the presence of "thickets of European Tree Mallow" (Malva dendromorpha), which was introduced to Australia.[11] This Malva dendromorpha originated in the coastal regions of the Mediterranean, where it relied on the salty water, "high levels of phosphorus", and consistent winds to grow and propagate.[11] Thus, it is well suited to grow on areas such as Seal Island and Middle Shag Island, which both have similar climates and habitats as Penguin Island. The main concern with the large population and high rate of growth of the European tree mallow was that when this plant died, it left the soil in a damaged state, and also left the ground largely exposed, meaning that the native Malva preissiana were exposed to the elements and as such, had less chance of successful growth.[28] The report also found that the presence of the native Malva preissiana played a key role in protecting other native shrubs that also sustain the soil quality: "the loss of native perennial shrubs which are constantly green and stabilise and maintain the shallow sandy topsoil".[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Malva preissiana". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- ^ Miquel, F.A.W. in Lehmann, J.G.C. (ed.) (1845), Malvaceae. Plantae Preissianae 1(2): 238

- ^ Australasian Virtual Herbarium: Malva preissiana. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Govaerts, R. et al. (2018) Plants of the world online:Malva preissiana. Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "Lavatera plebeia". Electronic Flora of South Australia Fact Sheet. State Herbarium of South Australia. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ Watson, P (2009). "Mallows-beyond cotton, hollyhocks and marshmallows". Australian Native Plants Society: 1–6.

- ^ "Spectacular Native Flora". Botanic Gardens & Parks Authority. Government of Western Australia.

- ^ "Preiss, J.A. Ludwig (1811 - 1883)". Australian National Herbarium. Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria.

- ^ "Mudbrick Herb Cottage". Herb Cottage.

- ^ "Malva preissiana Miq". Atlas of Living Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Labbe, A; Dunlop, J; Shepherd, J; Van Keulen, M (2017). "Restoration of native vegetation and re-introduction of Malva preissiana on Penguin Island – preliminary findings". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia: 1–3.

- ^ Rippey, E.; Rippey, J.; Dunlop, N. (2001). "Management of Indigenous and Alien Malvaceae on Islands near Perth, Western Australia" (PDF). Turning the Tide: The Eradication of Invasive Species: 1–420.

- ^ Medina, E; Garcia, V; Cuevas, E (1990). "Sclerophylly and Oligotrophic Environments: Relationships Between Leaf Structure, Mineral Nutrient Content, and Drought Resistance in Tropical Rain Forests of the Upper Rio Negro Region". Biotropica. 22 (1): 51–64. Bibcode:1990Biotr..22...51M. doi:10.2307/2388719. JSTOR 2388719.

- ^ Pyykkö, M (1966). "The leaf anatomy of East Patagonian xeromorphic plants". Annales Botanici Fennici: 453–622.

- ^ a b Local Land Services Western Region (2005). "Ecological Cultural Knowledge - Paakantyi (Barkindji)-Knowledge shared by the Paakantyi (Barkindji) people".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Conran, J; Barker, R; Rippey, E (2012). "alva weinmanniana (Besser ex Rchb.) Conran, a new name for the pink-flowered form of M. preissiana Schltdl. (Malvaceae)". Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens: 17–25.

- ^ a b Michael, P (2006). Agro-ecology of Malva parviflora (small-flowered mallow) in the Mediterranean-climatic agricultural region of Western Australian (PhD thesis). University of Western Australia.

- ^ a b Marchant, N; Wheeler, J; Bennett, E; Lander, N; McFarlane, T (1987). "Flora of the Perth Region". Western Australian Herbarium.

- ^ International Union for Conservation of Nature. "International Union for Conservation of Nature". Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Herb Cottage". Herb Cottage.

- ^ Ecology Australia, 2016

- ^ Rippey, E; Rippey, J; Dunlop, N (2001). "Management of Indigenous and Alien Malvaceae on Islands near Perth, Western Australia". Turning the Tide: The Eradication of Invasive Species: 1–420.

- ^ Labbe, Dunlop, Shephard, & Van Keulen, 2017

- ^ a b "Agriculture Victoria". Creeping Saltbush.

- ^ a b "Bower Spinach". Agriculture Victoria.

- ^ a b Dunlop, J; Johnstone, N (1994). "THE MIGRATION OF BRIDLED TERNS SIETNA ANACthEtUS BREEDING IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA". Australian Bird Study Association.

- ^ "My Tern: A Pocket Guide to the Terns of Australia". BirdLife Australia. 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Rippey, E; Dunlop, N; Rippey, J (2001). "Management of Indigenous and Alien Malvaceae on Islands near Perth, Western Australia". Turning the Tide: The Eradication of Invasive Species: 1–420.

External links

[edit]- VicFlora: Malva preissiana

- NT Flora factsheet: Malva preissiana

- PlantNet: Malva preissiana Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney.

- Florabase: Malva preissiana