Carl Sanders: Difference between revisions

Indy beetle (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Indy beetle (talk | contribs) adding info |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

=== Executive actions === |

=== Executive actions === |

||

Sanders appointed a Governor's Commission for Efficiency and Improvement in Government, which managed reforms in the penal system, mental healthcare, the civil service, |

Sanders appointed a Governor's Commission for Efficiency and Improvement in Government, which managed reforms in the penal system, mental healthcare, the civil service, the Highway Department, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Education.<ref name= davis/>{{sfn|Lauth|2021|p=25}} He worked with Atlanta mayor [[Ivan Allen Jr.]] to bring [[professional sports]] teams to the capital city,<ref name= cookNG/> and in 1963 he recruited a friend, [[Rankin M. Smith Sr.]], to fund the creation of the [[Atlanta Falcons]], a football team.<ref name= davis/> |

||

=== Legislative affairs === |

=== Legislative affairs === |

||

In 1963 [[Leroy Johnson (Georgia politician)|Leroy Johnson]] became the first black state senator in Georgia in decades. When guards at the State Capitol informed Sanders that Johnson and his black pages were ignoring signs designating "white" and "colored" restrooms and water fountains, the governor had the signage removed. Later, Johnson attempted to dine at the Commerce Club, an Atlanta venue frequented by legislators and other members of the state's political and economic elite. The white [[maître d']] refused Johnson service, so he contacted Sanders. Sanders called club founder [[Robert W. Woodruff]], who subsequently instructed the maître d' to serve Johnson.<ref>{{cite news| last = Galloway| first = Jim| title = How Leroy Johnson and Carl Sanders desegregated the state Capitol in 1963| newspaper = The Atlanta Journal-Constitution| date = October 24, 2019| url = https://www.ajc.com/blog/politics/how-leroy-johnson-and-carl-sanders-desegregated-the-state-capitol-1963/7tKi9xNsOqcZmUkFM34kLI/| access-date = May 27, 2022}}</ref> |

By the time Sanders became governor, it was common for this official to wield wide influence over the General Assembly, including being able to essentially name the [[List of speakers of the Georgia House of Representatives|Speaker of the House]] and legislative committee chairmen. He was one of the last governors to be able to exercise this amount of authority over the legislature.{{sfn|Lauth|2021|p=26}}<ref name= galloway/> In 1963 [[Leroy Johnson (Georgia politician)|Leroy Johnson]] became the first black state senator in Georgia in decades. When guards at the State Capitol informed Sanders that Johnson and his black pages were ignoring signs designating "white" and "colored" restrooms and water fountains, the governor had the signage removed. Later, Johnson attempted to dine at the Commerce Club, an Atlanta venue frequented by legislators and other members of the state's political and economic elite. The white [[maître d']] refused Johnson service, so he contacted Sanders. Sanders called club founder [[Robert W. Woodruff]], who subsequently instructed the maître d' to serve Johnson.<ref name= galloway>{{cite news| last = Galloway| first = Jim| title = How Leroy Johnson and Carl Sanders desegregated the state Capitol in 1963| newspaper = The Atlanta Journal-Constitution| date = October 24, 2019| url = https://www.ajc.com/blog/politics/how-leroy-johnson-and-carl-sanders-desegregated-the-state-capitol-1963/7tKi9xNsOqcZmUkFM34kLI/| access-date = May 27, 2022}}</ref> |

||

Sanders was a [[fiscal conservative]]. Most of Sanders' budgeting focus was directed at public education. His administration's 1963 budget recommendation to the General Assembly devoted 56 percent of expenditures to education. The following year he proposed several tax increases to raise additional funds for education, including a 50 cent increase on the tax per gallon on [[liquor]], a 12 cent increase on the tax per case of beer, 1% increase in the [[corporate income tax]], and the elimination of the vendors' commission on collection of the [[general sales tax]]. The Assembly incorporated his suggestions with minimal alterations. Over the course of his tenure, schoolteacher and university faculty salaries were raised and money was appropriated to build new educational institutions.{{sfn|Lauth|2021|p=25}} Georgia's economy performed well during his tenure, and the state had a budget surplus when he left office.{{sfn|Lauth|2021|pp=25–26}} |

|||

=== Political affairs === |

=== Political affairs === |

||

| Line 75: | Line 77: | ||

* {{cite book| last = Cook| first = James F.| chapter = Carl Sanders and the Politics of the Future| title = Georgia Governors in an Age of Change: From Ellis Arnall to George Busbee| editor-first= Henderson| editor-last= Harold P.| editor-first2= Roberts| editor-last2= Gary L.| publisher = University of Georgia Press| date = 1988| location = | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=yBkEAaFl4rkC| isbn = 9780820310053}} |

* {{cite book| last = Cook| first = James F.| chapter = Carl Sanders and the Politics of the Future| title = Georgia Governors in an Age of Change: From Ellis Arnall to George Busbee| editor-first= Henderson| editor-last= Harold P.| editor-first2= Roberts| editor-last2= Gary L.| publisher = University of Georgia Press| date = 1988| location = | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=yBkEAaFl4rkC| isbn = 9780820310053}} |

||

* {{cite journal| last = Hathorn| first = Billy Burton| title = The Frustration of Opportunity: Georgia Republicans and the Election of 1966| journal =Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South| volume = XXXI| issue = 4| pages = 37–52| edition = winter| date = 1987| issn = }} |

* {{cite journal| last = Hathorn| first = Billy Burton| title = The Frustration of Opportunity: Georgia Republicans and the Election of 1966| journal =Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South| volume = XXXI| issue = 4| pages = 37–52| edition = winter| date = 1987| issn = }} |

||

* {{cite book| last = Lauth| first = Thomas P.| title = Public Budgeting in Georgia: Institutions, Process, Politics and Policy| publisher = Springer| date = 2021| location = | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ymxAEAAAQBAJ | isbn = 9783030760236}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

Revision as of 06:53, 27 May 2022

Carl Sanders | |

|---|---|

| |

| 74th Governor of Georgia | |

| 74th Governor of Georgia Ambassador to | |

| In office January 15, 1963 – January 11, 1967 | |

| Lieutenant | Peter Geer |

| Preceded by | Ernest Vandiver |

| Succeeded by | Lester Maddox |

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office 1954–1956 | |

| Member of the Georgia Senate | |

| Ambassador to | |

| In office 1956–1962 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carl Edward Sanders May 15, 1925 Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | November 16, 2014 (aged 89) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Westover Memorial Park, Augusta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Betty Bird Foy |

| Alma mater | University of Georgia |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1943–1945 |

| Unit | U.S. Army Air Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

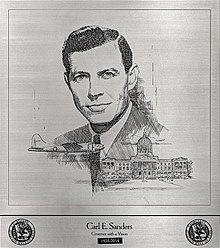

Carl Edward Sanders Sr. (May 15, 1925 – November 16, 2014) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 74th Governor of the state of Georgia from 1963 to 1967.

Early life and education

Carl Sanders was born on May 15, 1925 in Augusta, Georgia, United States to a middle class family. He later stated that he had "an exceptionally happy and secure childhood."[1] He attended the Academy of Richmond County, where he performed well academically and played on the school football team. He was made an alternate appointee to the United States Military Academy, but when the primary appointee claimed his spot Sanders accepted a football scholarship and enrolled at the University of Georgia[2] in 1942. He played as a left-handed quarterback on the freshman football team.[3]

While Sanders was at college, the United States entered World War II, and in 1943 he left his studies and joined the United States Army Air Forces. He was commissioned as a lieutenant and piloted B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft.[2] He named his own bomber "Georgia Peach", but was never deployed overseas.[3] After the war he returned to the University Georgia to complete his studies. He studied law, passing the bar examination in early 1947 and finishing his courses in December. He played with the Georgia Bulldogs and went to the Oil Bowl. He was a member of the Chi Phi fraternity, the Phi Kappa Literary Society, and the school debate team. On September 6, 1947 he married Betty Foy, an art student he had met at the university.[2] They had two children together.[3] Sanders started practicing law in Augusta with Henry Hammond before establishing his own practice with several other partners. He devoted a significant amount of time to practice early on to pay off medical debt after his wife fell ill.[4]

Legislative career

Sanders garnered an interest in politics from his father, who had served on the Richmond County Board of Commissioners. In 1954, Sanders won a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives,[5] successfully defeating a "Cracker Party" candidate.[3] Two years later he was elected to the Georgia State Senate. At the time, a rotation agreement meant the seat was typically held in successive fashion by a denizen of Richmond County, of Jefferson County, and Glascock County. He was re-elected in 1958 and 1960, making him the only person to ever serve three consecutive terms from a multi-county Georgia senatorial constituency while the rotation agreements were in use.[5] In 1958 he chaired a Senate committee which investigated corrupt highway development in Governor Marvin Griffin's administration. In the process he became political allies with Lieutenant Governor Ernest Vandiver,[3] who made him Senate floor leader in 1959.[5] Vandiver became governor, and that year a federal judge ordered the Atlanta Board of Education to draft a plan to racially desegregate schools. Vandiver called 60 people to the Governor's Mansion to discuss either proceeding with desegregation or closing the schools. Only Sanders and House floor leader Frank Twitty advised desegregation, the former fearing that suspending schools "would have created a generation of illiterates."[3] Vandiver ultimately had schools closed only temporarily while the Georgia General Assembly revised state segregation statutes.[3] Sanders served as president pro tempore of the chamber from 1960 to 1962.[5]

Gubernatorial career

1962 election

Sanders decided to make a bid for higher office in 1962.[5] Initially mulling over a potential race for the office of lieutenant governor which had a retiring incumbent, he had doubts when a similarly-named Atlanta attorney, Carl F. Sanders, declared his candidacy. Carl E. Sanders suspected that the other man had been planted to confuse voters and spoil his chances by another candidate, Peter Zack Geer. Geer denied the allegation. Carl E. Sanders then decided to run for governor. At the time he launched his candidacy in late April,[6] Georgia used the county unit system in its primaries, whereby the candidate who won the majority in most counties secured the party nomination, instead of the candidate which earned the majority of all votes across the state. This system greatly limited the chances of urban candidates for decades. Several weeks into the primary, federal courts declared this method unconstitutional, and left the nomination to be decided by popular vote.[5] Sanders campaigned on "a platform of progress", pledging to improve education, reorganize the State Highway Department, revamp mental health and penal institutions, recruit industry, and reapportion the General Assembly.[7]

Already seeking the nomination in the Democratic primary was former governor Marvin Griffin,[6] who was a staunch supporter of racial segregation.[5] He attacked Sanders as too young for the governorship and not committed enough to defending segregation.[8] Sanders supported segregation but felt it was useless to oppose federal integration orders.[9] He promised to "maintain Georgia's traditional separation"[5] but said he opposed race-baiting politics and that "I tip my hat to the past, but I take off my coat to the future."[10] Griffin held a rally with Alabama governor-elect George Wallace, another staunch segregationist, to demonstrate his support racial separation. Sanders mocked this strategy at his own rally the same day, describing Griffin as "so weak in his belief in Georgia and her people that he plans to import an outsider to meddle in our affairs. I don't need an Alabama crutch to help me."[10] Griffin pledged to oppose federal court orders to integrate and throughout the campaign vilified the "Negro bloc vote" in Georgia.[10] Following a confrontation between the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan and the Georgia State Patrol at a Klan rally, Griffin offered that he was unsure of how to handle such a situation. Sanders accused the former governor of having prior knowledge of the rally and of bring Klansmen into Georgia. Sanders also accused Griffin of having run a corrupt administration in his previous term.[8] In the primary, he defeated Griffin, receiving 494,978 votes (58.7 percent) to Griffin's 332,746 (39 percent).[11] Most of his support came from urban areas.[7] He then won the general election.[3] Aged 37 upon his inauguration, he was the youngest governor in the country at the time.[12]

Executive actions

Sanders appointed a Governor's Commission for Efficiency and Improvement in Government, which managed reforms in the penal system, mental healthcare, the civil service, the Highway Department, the Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Education.[3][13] He worked with Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. to bring professional sports teams to the capital city,[9] and in 1963 he recruited a friend, Rankin M. Smith Sr., to fund the creation of the Atlanta Falcons, a football team.[3]

Legislative affairs

By the time Sanders became governor, it was common for this official to wield wide influence over the General Assembly, including being able to essentially name the Speaker of the House and legislative committee chairmen. He was one of the last governors to be able to exercise this amount of authority over the legislature.[14][15] In 1963 Leroy Johnson became the first black state senator in Georgia in decades. When guards at the State Capitol informed Sanders that Johnson and his black pages were ignoring signs designating "white" and "colored" restrooms and water fountains, the governor had the signage removed. Later, Johnson attempted to dine at the Commerce Club, an Atlanta venue frequented by legislators and other members of the state's political and economic elite. The white maître d' refused Johnson service, so he contacted Sanders. Sanders called club founder Robert W. Woodruff, who subsequently instructed the maître d' to serve Johnson.[15]

Sanders was a fiscal conservative. Most of Sanders' budgeting focus was directed at public education. His administration's 1963 budget recommendation to the General Assembly devoted 56 percent of expenditures to education. The following year he proposed several tax increases to raise additional funds for education, including a 50 cent increase on the tax per gallon on liquor, a 12 cent increase on the tax per case of beer, 1% increase in the corporate income tax, and the elimination of the vendors' commission on collection of the general sales tax. The Assembly incorporated his suggestions with minimal alterations. Over the course of his tenure, schoolteacher and university faculty salaries were raised and money was appropriated to build new educational institutions.[13] Georgia's economy performed well during his tenure, and the state had a budget surplus when he left office.[16]

Political affairs

In 1964 Sanders appointed a biracial delegation to represent Georgia at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, the first time in decades that black people were represented on the delegation. Sanders explained, "[T]his is not a social club. This is purely a political organization, based on the fact that every voter should be represented."[17]

Under the term limit law then in effect, Sanders was ineligible to run for re-election in 1966. In the general election campaign that year, he endorsed Democratic nominee Lester Maddox, a segregationist, as his successor though the two had disagreed on many issues. At the Democratic State Convention in Macon on October 15, 1966, Sanders told the delegates: "A man should be loyal to his country, his family, to his God and to his political party—and don't you ever forget it."[18] In his speech, Sanders likened Maddox's Republican opponent, U.S. Representative Howard Callaway, to the "arrogance of Richard Nixon, the chameleon ability of Ronald Reagan to switch rather than fight, and the callous concern for human needs that is a throwback to McKinley, Harding, and Coolidge."[18] The Marietta Daily Journal said that Sanders in supporting Maddox had glorified party at the expense of statecraft.[19] Callaway criticized Sanders for mishandling the state budget surplus, a position which weakened the Republican among anti-Maddox moderate voters.[18] Callaway led Maddox in the popular vote but failed to win a majority, and the Democratic-controlled Georgia General Assembly chose Maddox as governor.

Later political activities

Sanders left office at the peak of his popularity and turned down several offers for federal government positions from President Johnson. Instead he returned to mount an unsuccessful campaign for governor in 1970 against future U.S. President Jimmy Carter. According to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution political reporter Bill Shipp, Carter employed race-baiting tactics to defeat Sanders in the Democratic primary.[20][21][22] Carter's campaign criticized Sanders for paying tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. and distributed grainy photographs of Sanders arm-in-arm with two black men. At the time, Sanders was part-owner of the Atlanta Hawks, and the two black men were Hawks players celebrating after a victory.[23] Carter won both the gubernatorial primary and the general election, and was later elected President of the United States in 1976. Sanders remained bitter about the 1970 campaign, and later said of Carter, "He is not proud of that election, and he shouldn't be proud of it."[3] He never pursued public office after his loss but remained an active fundraiser for Democratic candidates.[9]

Later life and death

In 1967 Sanders joined with several other lawyers to create the firm Troutman, Sanders, Lockerman & Ashmore[3] in Atlanta.[9] He renewed his focus on the firm—which was renamed Troutman Sanders in 1992—after his loss in the 1970 gubernatorial race and recruited Georgia Power and Southern Company as clients. He became chairman of First Georgia Bank in 1973. He served as chairman of the law firm for thirty years, and in 2006 became the its chairman emeritus. At the time of his death, Troutman Sanders had grown to include 600 lawyers.[3] Sanders died in Atlanta on November 16, 2014 at the age of 89, after a fall at his home.[24][25]

In recognition of his role in encouraging the construction and expansion of airports in Georgia, he was inducted into the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame in 1997.[26]

References

- ^ Cook 1988, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c Cook 1988, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Davis, Mark (November 17, 2014). "Former Georgia Gov. Sanders dies". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Cook 1988, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cook 1988, p. 171.

- ^ a b Buchanan 2011, p. 224.

- ^ a b Cook 1988, p. 173.

- ^ a b Buchanan 2011, p. 232.

- ^ a b c d Cook, James F. (September 12, 2002). "Carl Sanders (b. 1925)". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Buchanan 2011, p. 230.

- ^ Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections, p. 1677

- ^ Yardley, William (November 18, 2014). "Carl Sanders, 89, Dies; Led Georgia in '60s". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Lauth 2021, p. 25.

- ^ Lauth 2021, p. 26.

- ^ a b Galloway, Jim (October 24, 2019). "How Leroy Johnson and Carl Sanders desegregated the state Capitol in 1963". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Lauth 2021, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Ga. Gov To Lead Mixed Dem Delegation to Confab". Jet. Vol. XXVI, no. 19. August 13, 1964. p. 9.

- ^ a b c Hathorn 1987, p. 42.

- ^ Marietta Daily Journal, October 4, 1966

- ^ Torpy, Bill (November 19, 2014). "The political grudge Carl Sanders takes to his grave". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Sanders, Randy (1992). ""The Sad Duty of Politics": Jimmy Carter and the Issue of Race in His 1970 Gubernatorial Campaign". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 76 (3): 612–638. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 40582593.

- ^ Sanders, Randy (2007). Mighty Peculiar Elections: The New South Gubernatorial Campaigns of 1970 and the Changing Politics of Race. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807132906. OCLC 153582828.

- ^ David Freddoso, "Jimmy Carter's racist campaign of 1970" Washington Examiner, September 16, 2009

- ^ "|". Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ Yardley, William (November 18, 2014). "Carl Sanders, 89, Dies; Led Georgia in '60s". The New York Times.

- ^ "Carl E. Sanders". Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 2, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

Works cited

- Buchanan, Scott E. (2011). Some of the People Who Ate My Barbecue Didn't Vote for Me: The Life of Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 9780826517616.

- Cook, James F. (1988). "Carl Sanders and the Politics of the Future". In Harold P., Henderson; Gary L., Roberts (eds.). Georgia Governors in an Age of Change: From Ellis Arnall to George Busbee. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820310053.

- Hathorn, Billy Burton (1987). "The Frustration of Opportunity: Georgia Republicans and the Election of 1966". Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South. XXXI (4) (winter ed.): 37–52.

- Lauth, Thomas P. (2021). Public Budgeting in Georgia: Institutions, Process, Politics and Policy. Springer. ISBN 9783030760236.

External links

- 1925 births

- 2014 deaths

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century American politicians

- 21st-century American lawyers

- Academy of Richmond County alumni

- Accidental deaths from falls

- Accidental deaths in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Burials in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Georgia Bulldogs football players

- Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats

- Georgia (U.S. state) lawyers

- Governors of Georgia (U.S. state)

- Members of the Georgia House of Representatives

- Military personnel from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Politicians from Augusta, Georgia

- Presidents pro tempore of the Georgia State Senate

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

- University of Georgia alumni