Prehistoric Southern Africa: Difference between revisions

Resized |

Modified. Attribution: Blombos Cave. |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

In 92,000 BP, amid the [[Middle Stone Age]], Malawian [[foragers]] utilized [[Control of fire by early humans#Africa 2|fire]] to influence and alter their surrounding environment.<ref name="Thompson">{{cite journal |last1=Thompson |first1=Jessica C. |display-authors=etal |title=Early human impacts and ecosystem reorganization in southern-central Africa |journal=Science Advances |volume=7 |issue=19 |date=5 May 2021 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.abf9776 |pmid=33952528 |pmc=8099189 |bibcode=2021SciA....7.9776T |oclc=9579895150 |s2cid=233871035}}</ref> |

In 92,000 BP, amid the [[Middle Stone Age]], Malawian [[foragers]] utilized [[Control of fire by early humans#Africa 2|fire]] to influence and alter their surrounding environment.<ref name="Thompson">{{cite journal |last1=Thompson |first1=Jessica C. |display-authors=etal |title=Early human impacts and ecosystem reorganization in southern-central Africa |journal=Science Advances |volume=7 |issue=19 |date=5 May 2021 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.abf9776 |pmid=33952528 |pmc=8099189 |bibcode=2021SciA....7.9776T |oclc=9579895150 |s2cid=233871035}}</ref> |

||

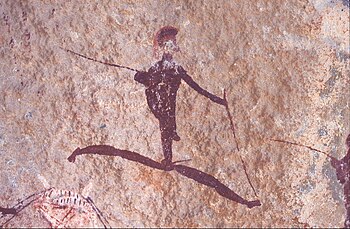

In 2011, archeologists found small rock fragment among spear points and other excavated material. After extensive testing for seven years, it was revealed that the nine red lines drawn on the rock were handmade and from an ochre crayon dating back 73,000 years. This makes it the oldest known abstract rock drawing.<ref name="Sample"/> The geometrical markings are an astonishing example of a very early creative behavior.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Historium|last=Nelson|first=Jo|publisher=Big Picture Press|year=2015|isbn=9781783701889|location=China|pages=8}}</ref> According to the research published in the journal Nature, the find was "a prime indicator of modern cognition" in our species and an ochre crayon was used by early African ''Homo sapiens'' inscribed onto the stone.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Henshilwood|first1=Christopher S.|last2=d'Errico|first2=Francesco|last3=van Niekerk|first3=Karen L.|last4=Dayet|first4=Laure|last5=Queffelec|first5=Alain|last6=Pollarolo|first6=Luca|date=2018-09-12|title=An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa|url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0514-3.epdf?referrer_access_token=CGqIHojCefPztRBh6DRcxtRgN0jAjWel9jnR3ZoTv0Om7oE8mgx5t97mBOHpTj1Gj1t2fwxXjVd-L6l4cK1MJCw2AvYkjoQQHrk9vHQX9XS2qdG0MWeecLm3MSe5iLphKLuow6w9b6Hz_GGHYel4IXudubkuP1_62HAbD6mTK-OGl9PTBqkmXwlaz6CiXlgiT4S7ZHH3ImWqa_2ekdUgST7Bq40oT798bTOlVwU5d3I=&tracking_referrer=www.bbc.com|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=562|issue=7725|pages=115–118|doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0514-3|pmid=30209394|bibcode=2018Natur.562..115H|s2cid=52197496|issn=0028-0836}}</ref> |

|||

Between 65,000 BP and 37,000 BP, amid the [[Late Stone Age#Transition from Middle Stone Age|Middle to Late Stone Age]], [[Khoisan|Southern Africans]] developed the [[bow and arrow]].<ref name="Hitchcock">{{cite journal |last1=Hitchcock |first1=Robert K. |last2=Crowell |first2=Aron |last3=Brooks |first3=Alison |title=The ethnoarchaeology of Ambush Hunting: A Case Study of ǂGi Pan, Western Ngamiland, Botswana |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332529080 |journal=African Archaeological Review |date=14 February 2019 |pages=119–144 |volume=36 |doi=10.1007/S10437-018-9319-X |issn=0263-0338 |oclc=8031623872 |s2cid=166634393}}</ref> |

Between 65,000 BP and 37,000 BP, amid the [[Late Stone Age#Transition from Middle Stone Age|Middle to Late Stone Age]], [[Khoisan|Southern Africans]] developed the [[bow and arrow]].<ref name="Hitchcock">{{cite journal |last1=Hitchcock |first1=Robert K. |last2=Crowell |first2=Aron |last3=Brooks |first3=Alison |title=The ethnoarchaeology of Ambush Hunting: A Case Study of ǂGi Pan, Western Ngamiland, Botswana |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332529080 |journal=African Archaeological Review |date=14 February 2019 |pages=119–144 |volume=36 |doi=10.1007/S10437-018-9319-X |issn=0263-0338 |oclc=8031623872 |s2cid=166634393}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:39, 7 July 2023

The prehistory of Southern Africa spans from the earliest human presence in the region until the emergence of the Iron Age in Southern Africa. In 1,000,000 BP, hominins controlled fire at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa.[1] Ancestors of the Khoisan may have expanded from East Africa or Central Africa into Southern Africa before 150,000 BP, possibly as early as before 260,000 BP.[2][3] Prehistoric West Africans may have diverged into distinct ancestral groups of modern West Africans and Bantu-speaking peoples in Cameroon, and, subsequently, around 5000 BP, the Bantu-speaking peoples migrated into other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Central African Republic, African Great Lakes, South Africa).[4]

Early Stone Age

In 1,000,000 BP, hominins controlled fire at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa.[1]

Middle Stone Age

Ancestors of the Khoisan may have expanded from East Africa or Central Africa into Southern Africa before 150,000 BP, possibly as early as before 260,000 BP.[2][5] Due to their early expansion and separation, ancestors of the Khoisan may have been the largest population among anatomically modern humans, from their early separation before 150,000 BP until the Out of Africa migration in 70,000 BP.[6]

In 200,000 BP, Africans (e.g., Khoisan of Southern Africa) bearing haplogroup L0 diverged from other Africans bearing haplogroup L1′6, which tend to be northward of Southern Africa.[7] Between 130,000 BP and 75,000 BP, behavioral modernity emerged among Southern Africans and long-term interactions between the regions of Southern Africa and Eastern Africa became established.[7]

By at least 170,000 BP, amid the Middle Stone Age, Southern Africans cooked and ate Hypoxis angustifolia rhizomes at Border Cave, South Africa, which may have provided carbohydrates for their migratory activities.[8]

In 92,000 BP, amid the Middle Stone Age, Malawian foragers utilized fire to influence and alter their surrounding environment.[9]

In 2011, archeologists found small rock fragment among spear points and other excavated material. After extensive testing for seven years, it was revealed that the nine red lines drawn on the rock were handmade and from an ochre crayon dating back 73,000 years. This makes it the oldest known abstract rock drawing.[10] The geometrical markings are an astonishing example of a very early creative behavior.[11] According to the research published in the journal Nature, the find was "a prime indicator of modern cognition" in our species and an ochre crayon was used by early African Homo sapiens inscribed onto the stone.[12]

Between 65,000 BP and 37,000 BP, amid the Middle to Late Stone Age, Southern Africans developed the bow and arrow.[13]

The Lebombo bone, which is from the Swaziland and South African mountain region and may be the oldest known mathematical artifact,[14] consists of 29 distinct notches that were deliberately cut into a baboon's fibula and has been dated to 35,000 BCE.[15][16]

Later Stone Age

The San populations, ancestral to the Khoisan, were spread throughout much of Southern Africa and Eastern Africa throughout the Later Stone Age in 75,000 BP. In 20,000 BP, these populations, who carried haplogroup L0d, may have further expanded, which may also be connected with the spread of click consonants into East African languages (Hadza language).[17]

The Later Stone Age Sangoan industry occupied Southern Africa in areas where annual rainfall is less than a meter (1000 mm; 39.4 in).[18]

In 19,000 BP, Africans, bearing haplogroup E1b1a-V38, likely traversed across the Sahara, from east to west.[4]

While the Niger-Congo migration may have been from West Africa into Kordofan, possibly from Kordofan, Sudan, Niger-Congo speakers[19] (e.g., Mande),[20] accompanied by undomesticated helmeted guineafowls, may have traversed into West Africa, domesticated the helmeted guineafowls by 3000 BCE, and via the Bantu expansion, traversed into other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa).[19]

According to Steverding (2020), while not definite: Near the African Great Lakes, schistosomes (e.g., S. mansoni, S. haematobium) underwent evolution.[21] Subsequently, there was an expansion alongside the Nile River.[21] From Egypt, the presence of schistosomes may have expanded, via migratory Yoruba people, into Western Africa.[21] Thereafter, schistosomes may have expanded, via migratory Bantu-speaking peoples, into the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Southern Africa, Central Africa).[21]

At Hora 1 rockshelter, in Malawi, an individual, dated between 16,897 BP and 15,827 BP, carried haplogroups B2b and L5b.[22]

At Hora 1 rockshelter, in Malawi, an individual, dated between 16,424 BP and 14,029 BP, carried haplogroups B2b1a2~ and L0d3/L0d3b.[22]

At Hora, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 10,000 BP and 5000 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0k2.[23]

During the early period of the Holocene, in 9000 BP, Khoisan-related peoples admixed with the ancestors of the Igbo people, possibly in the western Sahara.[24][25]

At Hora, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 8173 BP and 7957 BP, carried haplogroup L0a2.[23]

The genomes of Africans commonly found to undergo adaptation are regulatory DNA, and many cases of adaptation found among Africans relate to diet, physiology, and evolutionary pressures from pathogens.[26] Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, genetic adaptation (e.g., rs334 mutation, Duffy blood group, increased rates of G6PD deficiency, sickle cell disease) to malaria has been found among Sub-Saharan Africans, which may have initially developed in 7300 BP.[26] Sub-Saharan Africans have more than 90% of the Duffy-null genotype.[27] In the Kalahari Desert region of Africa, various possible genetic adaptations (e.g., adiponectin, body mass index, metabolism) have been found among the ǂKhomani people.[26] Sub-Saharan Africans have more than 90% of the Duffy-null genotype.[27] In South Africa, genetic adaptation (e.g., rs28647531 on chromosome 4q22) and strong susceptibility to tuberculosis has been found among Coloureds.[26]

At Fingira rockshelter, in Malawi, an individual, dated between 6179 BP and 2341 BP, carried haplogroups B2 and L0d1.[22]

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 6177 BP and 5923 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0d1c.[23]

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 6175 BP and 5913 BP, carried haplogroups BT and L0d1b2b.[23]

Bantu-speaking peoples migrated, along with their ceramics, from West Africa into other areas of Sub-Saharan Africa.[28] The Kalundu ceramic type may have spread into Southeastern Africa.[28] Additionally, the Eastern African Urewe ceramic type of Lake Victoria may have spread, via African shores near the Indian Ocean, as the Kwale ceramic type, and spread, via Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi, as the Nkope ceramic type.[28] From the region of Kenya and Tanzania to South Africa, eastern Bantu-speaking Africans constitute a north to south genetic cline; additionally, from eastern Africa to toward southern Africa, evidence of genetic homogeneity is indicative of a serial founder effect and admixture events having occurred between Bantu-speaking Africans and other African populations by the time the Bantu migration had spanned into South Africa.[26] Though some may have been created later, the earlier red finger-painted rock art may have been created between 6000 BP and 1800 BP, to the south of Kei River and Orange River by Khoisan hunter-gatherer-herders, in Malawi and Zambia by considerably dark-skinned, occasionally bearded, bow-and-arrow-wielding Akafula hunter-gatherers who resided in Malawi until 19th century CE, and in Transvaal by the Vhangona people.[29] Bantu-speaking farmers, or their Proto-Bantu progenitors, created the later white finger-painted rock art in some areas of Tanzania, Malawi, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, as well as in the northern regions of Mozambique, Botswana, and Transvaal.[29] The Transvaal (e.g., Soutpansberg, Waterberg) rock art was specifically created by Sotho-speakers (e.g., Birwa, Koni, Tlokwa) and Venda people.[29] Concentric circles, stylized humans, stylized animals, ox-wagons, saurian figures, Depictions of crocodiles and snakes were included in the white finger-painted rock art tradition, both of which were associated with rainmaking and crocodiles in particular, were also associated with fertility.[29] The white finger-painted rock art may have been created for reasons relating to initiation rites and puberty rituals.[29] Depictions from the rock art tradition of Bantu-speaking farmers have been found on divination-related items (e.g., drums, initiation figurines, initiation masks); fertility terracotta masks from Transvaal have been dated to the 1st millennium CE.[29] Along with Iron Age archaeological sites from the 1st millennium CE, this indicates that white finger-painted rock art tradition may have been spanned from the Early Iron Age to the Later Iron Age.[29] Down-headed animals, which appear in South African rock art, and portray shamanic animal sacrifice as a rainfall ritual, also appear in Round Head rock art.[30]

At Chencherere, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 5400 BP and 4800 BP, carried haplogroup L0k2.[23]

At Chencherere, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 5293 BP and 4979 BP, carried haplogroup L0k1.[23]

Pastoral Neolithic

Three Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers carried ancient DNA similar to Khoisan-speaking hunter-gatherers.[31] Prior to the Bantu migration into the region, as evidenced by ancient DNA from Botswana, East African herders migrated into Southern Africa.[31] Out of four Iron Age Bantu agriculturalists of West African origin, two earlier agriculturalists carried ancient DNA similar to Tsonga and Venda peoples and the two later agriculturalists carried ancient DNA similar to Nguni people; this indicates that there were various movements of peoples in the overall Bantu migration, which resulted in increased interaction and admixing between Bantu-speaking peoples and Khoisan-speaking peoples.[31] At Xaro, in Botswana, there were two individuals, dated to the Early Iron Age (1400 BP); one carried haplogroups E1b1a1a1c1a and L3e1a2, and another carried haplogroups E1b1b1b2b (E-M293, E-CTS10880) and L0k1a2.[32][33] At Taukome, in Botswana, an individual, dated to the Early Iron Age (1100 BP), carried haplogroups E1b1a1 (E-M2, E-Z1123) and L0d3b1.[32][33] At Nqoma, in Botswana, an individual, dated to the Early Iron Age (900 BP), carried haplogroup L2a1f.[32][33]

At Fingira, in Malawi, an individual, estimated to date between 2676 BP and 2330 BP, carried haplogroup L0f.[23]

As pastoralists and Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists may have begun arriving in Southern Africa in 2300 BP, Bantu-speaking agropastoralists and Khoisan hunter-gatherers may have admixed with one another, resulting in the development of blended agro-pastoralist and hunter-gatherer communities that languages with click consonants and Khoisan loan words; these amalgamated communities later would develop into the modern indigenous communities (e.g., Xhosa, Sotho, Tswana, Zulu people) of South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia.[34]

At Doonside, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2296 BP and 1910 BP, carried haplogroup L0d2.[35][36]

At St. Helena, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2241 BP and 1965 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2a and L0d2c1.[23]

At Ballito Bay, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2149 BP and 1932 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2 and L0d2a1.[35][36]

At Faraoskop Rock Shelter, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 2017 BP and 1748 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2a and L0d1b2b1b.[23]

At Ballito Bay, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 1986 BP and 1831 BP, carried haplogroups A1b1b2 and L0d2c1.[35][36]

At Ballito Bay, South Africa, Ballito Boy, estimated to date 1,980 ± 20 cal BP, was found to have Rickettsia felis.[37][38]

At Kasteelberg, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 1282 BP and 1069 BP, carried haplogroup L0d1a1a.[23]

At Eland Cave, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 533 BP and 453 BP, carried haplogroup L3e3b1.[35][36]

At Newcastle, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 508 BP and 327 BP, carried haplogroup L3e2b1a2.[35][36]

At Mfongosi, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 448 BP and 308 BP, carried haplogroup L3e1b2.[35][36]

At Champagne Castle, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date between 448 BP and 282 BP, carried haplogroup L0d2a1a.[35][36]

At Vaalkrans Shelter, in South Africa, an individual, estimated to date to 200 BP, is predominantly related to Khoisan speakers, partly related (15% - 32%) to East Africans, and carried haplogroups L0d3b1.[39]

References

- ^ a b Kaplan, Matt (2 April 2012). "Million-year-old ash hints at origins of cooking". Nature: nature.2012.10372. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10372. S2CID 177595396.

- ^ a b Schlebusch, Carina M.; Malmström, Helena; et al. (2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- ^ Estimated split times given in the source cited (in kya): Human-Neanderthal: 530-690, Deep Human [H. sapiens]: 250-360, NKSP-SKSP: 150-190, Out of Africa (OOA): 70–120.

- ^ a b Shriner, Daniel; Rotimi, Charles N. (2018). "Whole-Genome-Sequence-Based Haplotypes Reveal Single Origin of the Sickle Allele during the Holocene Wet Phase". American Journal of Human Genetics. 102 (4): 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.02.003. OCLC 8158698745. PMC 5985360. PMID 29526279. S2CID 4636822.

- ^ Estimated split times given in the source cited (in kya): Human-Neanderthal: 530-690, Deep Human [H. sapiens]: 250-360, NKSP-SKSP: 150-190, Out of Africa (OOA): 70–120.

- ^ Kim, Hie Lim; Ratan, Aakrosh; et al. (4 December 2014). "Khoisan hunter-gatherers have been the largest population throughout most of modern-human demographic history". Nature Communications. 5. Nature Publishing Group: 5692. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.5692K. doi:10.1038/ncomms6692. PMC 4268704. PMID 25471224.. Science, December 4, 2014

- ^ a b Sá, Luísa; et al. (16 August 2022). "Phylogeography of Sub-Saharan Mitochondrial Lineages Outside Africa Highlights the Roles of the Holocene Climate Changes and the Atlantic Slave Trade". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (16): 9219. doi:10.3390/ijms23169219. ISSN 1661-6596. OCLC 9627558751. PMC 9408831. PMID 36012483. S2CID 251653686.

- ^ Wadley, Lyn; Backwell, Lucinda; D'Errico, Francesco; Sievers, Christine (3 Jan 2020). "Cooked starchy rhizomes in Africa 170 thousand years ago". Science. 367 (6473): 87–91. Bibcode:2020Sci...367...87W. doi:10.1126/science.aaz5926. OCLC 8527136604. PMID 31896717. S2CID 209677578.

- ^ Thompson, Jessica C.; et al. (5 May 2021). "Early human impacts and ecosystem reorganization in southern-central Africa". Science Advances. 7 (19). Bibcode:2021SciA....7.9776T. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf9776. OCLC 9579895150. PMC 8099189. PMID 33952528. S2CID 233871035.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Samplewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Nelson, Jo (2015). Historium. China: Big Picture Press. p. 8. ISBN 9781783701889.

- ^ Henshilwood, Christopher S.; d'Errico, Francesco; van Niekerk, Karen L.; Dayet, Laure; Queffelec, Alain; Pollarolo, Luca (2018-09-12). "An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa". Nature. 562 (7725): 115–118. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..115H. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0514-3. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 30209394. S2CID 52197496.

- ^ Hitchcock, Robert K.; Crowell, Aron; Brooks, Alison (14 February 2019). "The ethnoarchaeology of Ambush Hunting: A Case Study of ǂGi Pan, Western Ngamiland, Botswana". African Archaeological Review. 36: 119–144. doi:10.1007/S10437-018-9319-X. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 8031623872. S2CID 166634393.

- ^ Helaine Selin (12 March 2008). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Encyclopaedia of the History of Science. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1356. Bibcode:2008ehst.book.....S. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ^ Pegg, Ed Jr. "Lebombo Bone". MathWorld.

- ^ Darling, David (2004). The Universal Book of Mathematics From Abracadabra to Zeno's Paradoxes. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-27047-8.

- ^ Rito, Teresa; Richards, Martin B.; et al. (2013). "The First Modern Human Dispersals across Africa". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80031. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880031R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080031. PMC 3827445. PMID 24236171.

- ^ Lee, Richard B. (1976), Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers: Studies of the ǃKung San and Their Neighbors, Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore, eds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- ^ a b Murunga, Philip; et al. (2018). "Mitochondrial DNA D-Loop Diversity of the Helmeted Guinea Fowls in Kenya and Its Implications on HSP70 Gene Functional Polymorphism". BioMed Research International. 2018: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2018/7314038. OCLC 8754386965. PMC 6258102. PMID 30539018. S2CID 54463512.

- ^ Welmers, WM E. (Aug 21, 2017). "Niger-Congo, Mande". Linguistics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 119. doi:10.1515/9783111562520-006. ISBN 9783111562520. OCLC 1039697513. S2CID 133735359.

- ^ a b c d Steverding, Dietmar (2020). "The spreading of parasites by human migratory activities". Virulence. 11 (1): 1177–1191. doi:10.1080/21505594.2020.1809963. PMC 7549983. PMID 32862777. S2CID 221383467.

- ^ a b c Lipson, Mark; et al. (23 February 2022). "Extended Data Table 1 Ancient individuals analysed in this study: Ancient DNA and deep population structure in sub-Saharan African foragers". Nature. 603 (7900): 290–296. Bibcode:2022Natur.603..290L. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04430-9. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 9437356581. PMC 8907066. PMID 35197631. S2CID 247083477.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Skoglund, Pontus; et al. (September 2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171 (1): 59–71.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. PMC 5679310. PMID 28938123.

- ^ Busby, George BJ; et al. (June 21, 2016). "Admixture into and within sub-Saharan Africa". eLife. 5: e15266. doi:10.7554/eLife.15266. PMC 4915815. PMID 27324836. S2CID 6885967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gurdasani, Deepti; et al. (December 3, 2014). "The African Genome Variation Project shapes medical genetics in Africa". Nature. 517 (7534): 327–332. Bibcode:2015Natur.517..327G. doi:10.1038/nature13997. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 9018039409. PMC 4297536. PMID 25470054. S2CID 4463627.

- ^ a b c d e Pfennig, Aaron; et al. (March 29, 2023). "Evolutionary Genetics and Admixture in African Populations". Genome Biology and Evolution. 15 (4): evad054. doi:10.1093/gbe/evad054. OCLC 9817135458. PMC 10118306. PMID 36987563. S2CID 257803764.

- ^ a b Wonkam, Ambroise; Adeyemo, Adebowale (March 8, 2023). "Leveraging our common African origins to understand human evolution and health" (PDF). Cell Genomics. 3 (3): 100278. doi:10.1016/j.xgen.2023.100278. PMC 10025516. PMID 36950382. S2CID 257458855.

- ^ a b c Vicente, Mario (2020). Demographic History and Adaptation in African Populations (PDF). Acta Universitatis Upsaliens Uppsala. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-91-513-0889-0. ISSN 1651-6214.

- ^ a b c d e f g Prins, Frans E.; Hall, Sian (1994). "Expressions of fertility, in the rock art of Bantu-speaking agriculturists" (PDF). African Archaeological Review. 12: 173–175, 197–198. doi:10.1007/BF01953042. ISSN 0263-0338. JSTOR 25130575. OCLC 5547024308. S2CID 162185643.

- ^ Soukopova, Jitka (September 2015). "Tassili Paintings: Ancient roots of current African beliefs?". Expression: 116–119. ISSN 2499-1341.

- ^ a b c Choudhury, Ananyo; et al. (April 2021). "Bantu-speaker migration and admixture in southern Africa". Human Molecular Genetics. 30 (R1): R56–R63. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddaa274. PMC 8117461. PMID 33367711.

- ^ a b c Wang, Ke; et al. (June 2020). "Ancient genomes reveal complex patterns of population movement, interaction, and replacement in sub-Saharan Africa". Science Advances. 6 (24): eaaz0183. Bibcode:2020SciA....6..183W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz0183. PMC 7292641. PMID 32582847.

- ^ a b c Wang, Ke; et al. (June 2020). "Supplementary Materials for Ancient genomes reveal complex patterns of population movement, interaction, and replacement in sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). Science Advances. 6 (24): eaaz0183. Bibcode:2020SciA....6..183W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz0183. PMC 7292641. PMID 32582847.

- ^ Petersen, Desiree C.; Libiger, Ondrej; Tindall, Elizabeth A.; Hardie, Rae-Anne; Hannick, Linda I.; Glashoff, Richard H.; Mukerji, Mitali; Fernandez, Pedro; Haacke, Wilfrid; Schork, Nicholas J.; Hayes, Vanessa M. (14 March 2013). "Complex Patterns of Genomic Admixture within Southern Africa". PLOS Genetics. 9 (3): e1003309. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003309. PMC 3597481. PMID 23516368.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Schlebusch, Carina M.; et al. (November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970. S2CID 206663925.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schlebusch, Carina M.; et al. (3 November 2017). "Supplementary Materials for Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago" (PDF). Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970. S2CID 206663925.

- ^ Rifkin, Riaan F.; et al. (March 3, 2023). "Rickettsia felis DNA recovered from a child who lived in southern Africa 2000 years ago". Communications Biology. 6 (1): 240. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-04582-y. OCLC 9786799123. PMC 9984395. PMID 36869137. S2CID 257312840.

- ^ Rifkin, Riaan F.; et al. (March 3, 2023). "Supplementary Notes 1-7 for Rickettsia felis DNA recovered from a child who lived in southern Africa 2,000 years ago" (PDF). Communications Biology. 6 (1): 240. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-04582-y. OCLC 9786799123. PMC 9984395. PMID 36869137. S2CID 257312840.

- ^ Coutinho, Alexandra; et al. (April 2021). "Later Stone Age human hair from Vaalkrans Shelter, Cape Floristic Region of South Africa, reveals genetic affinity to Khoe groups". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 174 (4): 701–713. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24236. ISSN 0002-9483. OCLC 8971087113. PMID 33539553. S2CID 213563734.