Alliterative verse: Difference between revisions

Changing title to more accurately capture the content that will be there once all the docmentation is put in -- that we have a genuine alliterative revival in the present. |

added diction section for old english |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

====Rules for alliteration==== |

====Rules for alliteration==== |

||

Old English follows the general rules for Germanic alliteration. The first stressed syllable of the off-verse, or second half-line, usually alliterates with one or both of the stressed syllables of the on-verse, or first half-line. The second stressed syllable of the off-verse does not usually alliterate with the others. Note that Old English only requires '''one''' alliteration in each half-line, unlike Middle English, which normally requires '''both''' lifts in the on-verse to be alliterated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Terasawa |first=Jun |title=Old English Metre: An Introduction |publisher=University of Toronto Press. |year=2011 |pages=60}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Russom |first=Geoffrey |title=Evolution of the a-verse in English alliterative meter |date=2007-05-18 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110198515.1.63 |work=Studies in the History of the English Language III |pages=63–88 |access-date=2023-11-30 |publisher=Mouton de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-019089-2}}</ref> |

Old English follows the general rules for Germanic alliteration. The first stressed syllable of the off-verse, or second half-line, usually alliterates with one or both of the stressed syllables of the on-verse, or first half-line. The second stressed syllable of the off-verse does not usually alliterate with the others. Note that Old English only requires '''one''' alliteration in each half-line, unlike Middle English, which normally requires '''both''' lifts in the on-verse to be alliterated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Terasawa |first=Jun |title=Old English Metre: An Introduction |publisher=University of Toronto Press. |year=2011 |pages=60}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Russom |first=Geoffrey |title=Evolution of the a-verse in English alliterative meter |date=2007-05-18 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110198515.1.63 |work=Studies in the History of the English Language III |pages=63–88 |access-date=2023-11-30 |publisher=Mouton de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-019089-2}}</ref> |

||

====Diction==== |

|||

Old English was rich in poetic synonyms and kennings.<ref>{{Citation |last=Lester |first=G. A. |title=Old English Poetic Diction |date=1996 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24561-1_4 |work=The Language of Old and Middle English Poetry |pages=47–66 |access-date=2023-12-01 |place=London |publisher=Macmillan Education UK |isbn=978-0-333-48847-8}}</ref> For instance, the Old English poet could deploy a wide array of synonyms and kennings to refer to the sea: ''sæ, mere, deop wæter, seat wæter, hæf, geofon, windgeard, yða ful, wæteres hrycg, garsecg, holm, wægholm, brim, sund, floð, ganotes bæð, swanrad, seglrad,'' among others. This ranges from synonyms surviving in English, like ''sea'' and ''mere'', to rarer poetic words and compounds, to full-on kennings like "gannet's bath", "whale-road", or "seal-road".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hill |first=Archibald A. |last2=Lind |first2=L. R. |date=1953 |title=Studies in Honor of Albert Morey Sturtevant |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/409975 |journal=Language |volume=29 |issue=4 |pages=547 |doi=10.2307/409975 |issn=0097-8507}}</ref> |

|||

Further details about Old English versification can be found in the companion article, [[Old English metre|Old English Meter]]. |

Further details about Old English versification can be found in the companion article, [[Old English metre|Old English Meter]]. |

||

| Line 101: | Line 104: | ||

The survival -- or revival -- of alliterative verse in 14th Century England makes it, like Iceland, an outlier in medieval Christian culture, which came to be dominated by Latin and Romance verse forms and literary traditions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pearsall |first=Derek |last2=Burrow |first2=J. A. |date=1986 |title=Medieval Writers and Their Work: Middle English Literature and Its Background 1100-1500 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3728781 |journal=The Modern Language Review |volume=81 |issue=1 |pages=164 |doi=10.2307/3728781 |issn=0026-7937}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |title=English Alliterative Verse |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2016}}</ref> Alliterative verse in post-Conquest England had to compete with imported, often French-derived forms in rhyming stanzas, reflecting what must have seemed like the common practice of the rest of Christendom.<ref>{{Cite book |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198827429.001.0001 |title=The Oxford History of Poetry in English |date=2023-05-18 |publisher=Oxford University PressOxford |isbn=0-19-882742-3 |editor-last=Cooper |editor-first=Helen |editor-last2=Edwards |editor-first2=Robert R.}}</ref> Despite these disadvantages, alliterative verse became the preferred English meter for historical romances, especially those concerned with the so-called Arthurian "Matter of Britain",<ref>{{Cite journal |last=KOSSICK |first=SHIRLEY |date=1979 |title=EPIC AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH ALLITERATIVE REVIVAL |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00138397908690761 |journal=English Studies in Africa |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=71–82 |doi=10.1080/00138397908690761 |issn=0013-8398}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Moran |first=Patrick |title=Text-Types and Formal Features |date=2017-06-26 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110432466-005 |work=Handbook of Arthurian Romance |pages=59–78 |access-date=2023-11-30 |publisher=De Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-043246-6}}</ref> and to be a common mode for political protest, through Piers Plowman and a variety of political prophesies.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |date=2019 |title=Political Prophecy and the Form of <i>Piers Plowman</i> |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1484/j.viator.5.121362 |journal=Viator |volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=207–247 |doi=10.1484/j.viator.5.121362 |issn=0083-5897}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Piers Plowman and Other Alliterative Poems |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203392737_chapter_xv |work=THE MIDDLE AGES |pages=240–248 |access-date=2023-11-30 |place=Abingdon, UK |publisher=Taylor & Francis}}</ref> However, as with Icelandic [[Rímur|rimur]], many 14th-Century poems combine alliteration with rhyming stanzas.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Duggan |first=Hoyt N. |date=1977 |title=Strophic Patterns in Middle English Alliterative Poetry |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/390723 |journal=Modern Philology |volume=74 |issue=3 |pages=223–247 |doi=10.1086/390723 |issn=0026-8232}}</ref> Increasingly, however, the alliterative verse tradition was marginalized relative to other English verse traditions, most notably the metrical, rhyming tradition associated with Geoffrey Chaucer.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |title=Meter and Modernity in English Verse, 1350-1650 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2021}}</ref> |

The survival -- or revival -- of alliterative verse in 14th Century England makes it, like Iceland, an outlier in medieval Christian culture, which came to be dominated by Latin and Romance verse forms and literary traditions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pearsall |first=Derek |last2=Burrow |first2=J. A. |date=1986 |title=Medieval Writers and Their Work: Middle English Literature and Its Background 1100-1500 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3728781 |journal=The Modern Language Review |volume=81 |issue=1 |pages=164 |doi=10.2307/3728781 |issn=0026-7937}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |title=English Alliterative Verse |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2016}}</ref> Alliterative verse in post-Conquest England had to compete with imported, often French-derived forms in rhyming stanzas, reflecting what must have seemed like the common practice of the rest of Christendom.<ref>{{Cite book |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198827429.001.0001 |title=The Oxford History of Poetry in English |date=2023-05-18 |publisher=Oxford University PressOxford |isbn=0-19-882742-3 |editor-last=Cooper |editor-first=Helen |editor-last2=Edwards |editor-first2=Robert R.}}</ref> Despite these disadvantages, alliterative verse became the preferred English meter for historical romances, especially those concerned with the so-called Arthurian "Matter of Britain",<ref>{{Cite journal |last=KOSSICK |first=SHIRLEY |date=1979 |title=EPIC AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH ALLITERATIVE REVIVAL |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00138397908690761 |journal=English Studies in Africa |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=71–82 |doi=10.1080/00138397908690761 |issn=0013-8398}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Moran |first=Patrick |title=Text-Types and Formal Features |date=2017-06-26 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110432466-005 |work=Handbook of Arthurian Romance |pages=59–78 |access-date=2023-11-30 |publisher=De Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-043246-6}}</ref> and to be a common mode for political protest, through Piers Plowman and a variety of political prophesies.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |date=2019 |title=Political Prophecy and the Form of <i>Piers Plowman</i> |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1484/j.viator.5.121362 |journal=Viator |volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=207–247 |doi=10.1484/j.viator.5.121362 |issn=0083-5897}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Piers Plowman and Other Alliterative Poems |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203392737_chapter_xv |work=THE MIDDLE AGES |pages=240–248 |access-date=2023-11-30 |place=Abingdon, UK |publisher=Taylor & Francis}}</ref> However, as with Icelandic [[Rímur|rimur]], many 14th-Century poems combine alliteration with rhyming stanzas.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Duggan |first=Hoyt N. |date=1977 |title=Strophic Patterns in Middle English Alliterative Poetry |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/390723 |journal=Modern Philology |volume=74 |issue=3 |pages=223–247 |doi=10.1086/390723 |issn=0026-8232}}</ref> Increasingly, however, the alliterative verse tradition was marginalized relative to other English verse traditions, most notably the metrical, rhyming tradition associated with Geoffrey Chaucer.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Weiskott |first=Eric |title=Meter and Modernity in English Verse, 1350-1650 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2021}}</ref> |

||

==== Types of Middle English Alliterative Verse ==== |

==== Types of Middle English Alliterative Verse ==== |

||

Middle English alliterative verse fell into several typical categories. There were the Arthurian romances, such as [[Layamon's Brut|Layamon's ''Brut'']], the ''[[Alliterative Morte Arthure|Alliterative Morte Arthur]]'', [[Sir Gawain and the Green Knight|''Sir Gawain and the Green Knigh''t]], ''[[The Awntyrs off Arthure|Awyntyrs off Arthure]]'', ''[[The Avowing of Arthur]]'', ''[[Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle|Sir Gawain and the Carl of Carlisle]]'', ''[[The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain]]'', and ''Charlemagne and Ralph the Collier''. There were accounts of warfare, like the ''Siege of Jerusalem'' and '' |

Middle English alliterative verse fell into several typical categories. There were the Arthurian romances, such as [[Layamon's Brut|Layamon's ''Brut'']], the ''[[Alliterative Morte Arthure|Alliterative Morte Arthur]]'', [[Sir Gawain and the Green Knight|''Sir Gawain and the Green Knigh''t]], ''[[The Awntyrs off Arthure|Awyntyrs off Arthure]]'', ''[[The Avowing of Arthur]]'', ''[[Sir Gawain and the Carle of Carlisle|Sir Gawain and the Carl of Carlisle]]'', ''[[The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain]]'', and ''Charlemagne and Ralph the Collier''. There were accounts of warfare, like the ''Siege of Jerusalem'' and ''Scotish Feilde''. There were poems devoted to Biblical stories, Christian virtues, and religious allegory, and religious instruction, like ''[[Cleanness]]'', ''Patience'', ''Pearl'', ''[[The Three Dead Kings]]'', ''[[The Castle of Perseverance]]'', the [[York Mystery Plays|York]], [[Chester Mystery Plays|Chester]], and other municipal [[Mystery play|mystery plays]], ''[[St. Erkenwald (poem)|St. Erkenwald]]'', the ''Pistil of Swete Susan'', or ''Pater Noster''. And there were a variety of poems falling in a space that ranged from allegory to satire to political commentary, including ''[[Piers Plowman]]'', ''[[Wynnere and Wastoure|Winnere and Wastoure]]'', ''[[Mum and the Sothsegger|Mum and the Sothsegger,]]'' ''The Parlement of Three Ages'', ''The Buke of the Howlat, [[Richard the Redeless]]'', ''[[Jack Upland]]'', ''[[Friar Daw's Reply]]'', ''Jack Uplands Rejoinder, The Blacksmiths, [[Tournament of Tottenham|The Tournament of Tottenham]], Sum Practysis of Medecyne'', and ''The Tretis of the Twa Mariit Women and the Wedo.''<ref>{{Cite web |title=Medieval Institute Publications {{!}} Western Michigan University Research {{!}} ScholarWorks at WMU |url=https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/medievalpress/ |access-date=2023-12-01 |website=scholarworks.wmich.edu}}</ref> |

||

==== Metrical Form ==== |

==== Metrical Form ==== |

||

Revision as of 02:12, 1 December 2023

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principle ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme.[1] The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics.[2] The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse.[3][4][5][6]

While alliteration is common in many poetic traditions, it is 'relatively infrequent' as a structured characteristic of poetic form.[7]: 41 However, structural alliteration appears in a variety of poetic traditions, including Old Irish, Welsh, Somali and Mongol poetry.[8][9][10][11] The extensive use of alliteration in the so-called Kalevala meter of the Finnic languages provides a close comparison, and may derive directly from Germanic-language alliterative verse.[12]

Unlike in other Germanic languages, where alliterative verse has largely fallen out of use (except for deliberate revivals, like Richard Wagner's 19th-century German Ring Cycle[13]), alliteration has remained a vital feature of Icelandic poetry.[14] After the 14th Century, Icelandic alliterative poetry mostly consisted of rímur,[15] a verse form which combines alliteration with rhyme. The most common alliterative ríma form is ferskeytt, a kind of quatrain.[16] Examples of rimur include Disneyrímur by Þórarinn Eldjárn, ''Unndórs rímur'' by an anonymous author, and the rimur transformed to post-rock anthems by Sigur Ros.[17] From 19th century poets like Jonas Halgrimsson[18] to 21st-century poets like Valdimar Tómasson, alliteration has remained a prominent feature of modern Icelandic literature, though contemporary Icelandic poets vary in their adherence to traditional forms.[19]

By the early 19th century, alliterative verse in Finnish was largely restricted to traditional, largely rural folksongs, until Elias Lönnrot and his compatriots collected them and published them as the Kalevala, which rapidly became the national epic of Finland and contributed to the Finnish independence movement.[20] This led to poems in Kalevala meter becoming a signicant element in Finnish literature[21][22] and popular culture.[23]

Alliterative verse has also been revived in Modern English.[24][25] Many modern authors include alliterative verse among their compositions, including Poul Anderson, W.H. Auden, Fred Chappell, Richard Eberhart, John Heath-Stubbs, C. Day Lewis, C.S. Lewis, Ezra Pound, John Myers Myers, Patrick Rothfuss, L. Sprague de Camp, J. R. R. Tolkien and Richard Wilbur.[26][25] Modern English alliterative verse covers a wide range of styles and forms, ranging from poems in strict Old English or Old Norse meters, to highly alliterative free verse that uses strong-stress alliteration to connect adjacent phrases without strictly linking alliteration to line structure.[27] While alliterative verse is relatively popular in the speculative fiction (specifically, the speculative poetry) community,[28][29] and is regularly featured at events sponsored by the Society for Creative Anachronism,[28][30] it also appears in poetry collections published by a wide range of practicing poets.[31]

Common Germanic origins and features

The poetic forms found in the various Germanic languages are not identical, but there is still sufficient similarity to make it clear that they are closely related traditions, stemming from a common Germanic source. Knowledge about that common tradition, however, is based almost entirely on inference from later poetry.[32]

Originally all alliterative poetry was composed and transmitted orally, and much went unrecorded. The degree to which writing may have altered this oral art form remains much in dispute. Nevertheless, there is a broad consensus among scholars that the written verse retains many (and some would argue almost all) of the features of the spoken language.[33][34][35]

One statement we have about the nature of alliterative verse from a practising alliterative poet is that of Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda. He describes metrical patterns and poetic devices used by skaldic poets around the year 1200.[36] Snorri's description has served as the starting point for scholars to reconstruct alliterative meters beyond those of Old Norse.[37][38]

Alliterative verse has been found in some of the earliest monuments of Germanic literature. The Golden Horns of Gallehus, discovered in Denmark and likely dating to the 4th century, bear this Runic inscription in Proto-Norse:[39]

x / x x x / x x / x / x x ek hlewagastiʀ holtijaʀ || horna tawidō (I, Hlewagastiʀ [son?] of Holt, made the horn.)

This inscription contains four strongly stressed syllables, the first three of which alliterate on ⟨h⟩ /x/ and the last of which does not alliterate, essentially the same pattern found in much later verse.

Metrical form

The core metrical features of traditional Germanic alliterative verse are as follows; they can be seen in the Gallehus inscription above:[40]

- A long line is divided into two half-lines. Half-lines are also known as 'verses', 'hemistichs', or 'distichs'; the first is called the 'a-verse' (or 'on-verse'), the second the 'b-verse' (or 'off-verse').[a] The rhythm of the b-verse is generally more regular than that of the a-verse, helping listeners to perceive where the end of the line falls.[40]

- A heavy pause, or 'cæsura', separates the verses.[40]

- Each verse usually has two heavily stressed syllables, referred to as 'lifts' or 'beats' (other, less heavily stressed syllables, are called 'dips').[40]

- The first (and, if there is one, sometimes the second) lift in the a-verse alliterates with the first lift in the b-verse.[40]

- The second lift in the b-verse does not alliterate with the first lifts.[40]

Some of these fundamental rules varied in certain traditions over time. Unlike in post-medieval English accentual verse, in which a syllable is either stressed or unstressed, Germanic poets were sensitive to degrees of stress. These can be thought of at three levels:[40]

- most stressed ('stress-words'): root syllables of nouns, adjectives, participles, infinitives[40]

- less stressed ('particles'): root syllables of most finite verbs (i.e. verbs which are not infinitives) and adverbs[40]

- even less stressed ('proclitics'): most pronouns, weakly stressed adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, parts of the verb to be, word-endings[40]

If a half-line contains one or more stress-words, their root syllables will be the lifts. (This is the case in the Gallehus Horn inscription above, where all the lifts are nouns.) If it contains no stress-words, the root syllables of any particles will be the lift. Rarely, even a proclitic can be the lift, either because there are no more heavily stressed syllables or because it is given extra stress for some particular reason.[41][42]

If a lift was occupied by word with a short root vowel followed by only one consonant followed by an unstressed vowel (i.e. '(-)CVCV(-)) these two syllables were in most circumstances counted as only one syllable. This is called resolution.[43]

The patterns of unstressed syllables vary significantly in the alliterative traditions of different Germanic languages. The rules for these patterns remain imperfectly understood and subject to debate.[44]

Rules for alliteration

Alliteration fits naturally with the prosodic patterns of early Germanic languages. Alliteration essentially involves matching the left edges of stressed syllables. Early Germanic languages share a left-prominent prosodic pattern. In other words, stress falls on the root syllable of a word, which is normally the initial syllable (except where the root is preceded by an unstressed prefix, as in past participles, for example). This means that the first sound of a word was particularly salient to listeners.[45] Traditional Germanic verse had two particular rules about alliteration:

- All vowels alliterate with each other.[46] The precise reasons for this are debated. The most common, but not uniformly accepted, theory for vowel-alliteration is that words beginning with vowels all actually began with a glottal stop (as is still the case in some modern Germanic languages).[46]

- The consonant clusters st-, sp- and sc- are treated as separate sounds (so st- only alliterates with st-, not with s- or sp-).[47]

Diction

The need to find an appropriate alliterating word gave certain other distinctive features to alliterative verse as well. Alliterative poets drew on a specialized vocabulary of poetic synonyms rarely used in prose texts[48][49] and used standard images and metaphors called kennings.[50][51][52]

Old Saxon and medieval English attest to the word fitt with the sense of 'a section in a longer poem', and this term is sometimes used today by scholars to refer to sections of alliterative poems.[53][54]

English alliterative verse

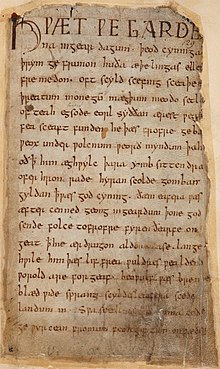

Old English

Old English classical poetry, epitomised by Beowulf, follows the rules of traditional Germanic poetry outlined above, and is indeed a major source for reconstructing them.[55] J.R.R. Tolkien's essay "On Translating Beowulf" analyses the rules as used in the poem.[56] Old English poetry, even after the introduction of Christianity, was uniformly written in alliterative verse, and much of the literature written in Old English, such as the Dream of the Rood, is explicitly Christian,[57] though poems like Beowulf demonstrate continuing cultural memory for the Pagan past.[58] Alliterative verse was so strongly entrenched in Old English society that English monks, writing in Latin, would sometimes create Latin approximations to alliterative verse.[59]

Types of Old English Alliterative Verse

Old English alliterative verse comes in a variety of forms. It includes heroic poetry like Beowulf, The Battle of Brunanburh, or The Battle of Maldon; elegiac or "wisdom" Poetry like The Ruin or The Wanderer, riddles, translations of classical and Latin Poetry, saints' lives, poetic Biblical paraphrases, oOriginal Christian poems, charms, mnemonic poems used to memorize information, and the like.[60]

Metrical form

As described above for the Germanic tradition as a whole, each line of poetry in Old English consists of two half-lines or verses with a pause or caesura in the middle of the line. Each half-line usually has two accented syllables, although the first may only have one. The following example from the poem The Battle of Maldon, spoken by the warrior Beorhtwold, shows the usual pattern:

Hige sceal þe heardra, heorte þe cēnre, |

Will must be the harder, courage the bolder, |

Note the single alliteration per half-line in the third line. Clear indications of Modern English meanings can be heard in the original, using phonetic approximations of the Old English sound-letter system:

- High [courage] shall the harder, heart the keener,

- mood shall the more, as our main [might] littleth

- here lies our elder all for-heaved

Single 'half-lines' are sometimes found in Old English verse; scholars debate how far these were a characteristic of Old English poetic tradition and how far they arise from defective copying of poems by scribes.[61][62]

Rules for alliteration

Old English follows the general rules for Germanic alliteration. The first stressed syllable of the off-verse, or second half-line, usually alliterates with one or both of the stressed syllables of the on-verse, or first half-line. The second stressed syllable of the off-verse does not usually alliterate with the others. Note that Old English only requires one alliteration in each half-line, unlike Middle English, which normally requires both lifts in the on-verse to be alliterated.[63][64]

Diction

Old English was rich in poetic synonyms and kennings.[65] For instance, the Old English poet could deploy a wide array of synonyms and kennings to refer to the sea: sæ, mere, deop wæter, seat wæter, hæf, geofon, windgeard, yða ful, wæteres hrycg, garsecg, holm, wægholm, brim, sund, floð, ganotes bæð, swanrad, seglrad, among others. This ranges from synonyms surviving in English, like sea and mere, to rarer poetic words and compounds, to full-on kennings like "gannet's bath", "whale-road", or "seal-road".[66]

Further details about Old English versification can be found in the companion article, Old English Meter.

The Middle English "Alliterative Revival"

Just as rhyme was seen in some Anglo-Saxon poems (e.g. The Rhyming Poem, and, to some degree, The Proverbs of Alfred), the use of alliterative verse continued (or was revived) in Middle English, though which it was -- continuation, or revival -- is a matter of some debate.[67][68][69] Layamon's Brut, written in about 1215, uses what seems like a loose alliterative meter in comparison with pre-Conquest alliterative verse.[70] Starting in the mid-14th century, alliterative verse became popular in the English North, the West Midlands, and a little later in Scotland[71]. The Pearl Poet uses a complex scheme of alliteration, rhyme, and iambic metre in his Pearl; a more conventional alliterative metre in Cleanness and Patience, and alliterative verse alternating with rhymed quatrains in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[72] William Langland's Piers Plowman is another important English alliterative poem; it was written between c. 1370 and 1390.[73]

Historical Context

The survival -- or revival -- of alliterative verse in 14th Century England makes it, like Iceland, an outlier in medieval Christian culture, which came to be dominated by Latin and Romance verse forms and literary traditions.[74][75] Alliterative verse in post-Conquest England had to compete with imported, often French-derived forms in rhyming stanzas, reflecting what must have seemed like the common practice of the rest of Christendom.[76] Despite these disadvantages, alliterative verse became the preferred English meter for historical romances, especially those concerned with the so-called Arthurian "Matter of Britain",[77][78] and to be a common mode for political protest, through Piers Plowman and a variety of political prophesies.[79][80] However, as with Icelandic rimur, many 14th-Century poems combine alliteration with rhyming stanzas.[81] Increasingly, however, the alliterative verse tradition was marginalized relative to other English verse traditions, most notably the metrical, rhyming tradition associated with Geoffrey Chaucer.[82]

Types of Middle English Alliterative Verse

Middle English alliterative verse fell into several typical categories. There were the Arthurian romances, such as Layamon's Brut, the Alliterative Morte Arthur, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Awyntyrs off Arthure, The Avowing of Arthur, Sir Gawain and the Carl of Carlisle, The Knightly Tale of Gologras and Gawain, and Charlemagne and Ralph the Collier. There were accounts of warfare, like the Siege of Jerusalem and Scotish Feilde. There were poems devoted to Biblical stories, Christian virtues, and religious allegory, and religious instruction, like Cleanness, Patience, Pearl, The Three Dead Kings, The Castle of Perseverance, the York, Chester, and other municipal mystery plays, St. Erkenwald, the Pistil of Swete Susan, or Pater Noster. And there were a variety of poems falling in a space that ranged from allegory to satire to political commentary, including Piers Plowman, Winnere and Wastoure, Mum and the Sothsegger, The Parlement of Three Ages, The Buke of the Howlat, Richard the Redeless, Jack Upland, Friar Daw's Reply, Jack Uplands Rejoinder, The Blacksmiths, The Tournament of Tottenham, Sum Practysis of Medecyne, and The Tretis of the Twa Mariit Women and the Wedo.[83]

Metrical Form

The form of alliterative verse changed gradually over time.[84] Layamon's Brut retained many features of Old English verse, along with significant changes in meter. By the 14th Century, the Middle English alliterative long line had emerged, which was rhythmically very different from the Old English meter. In Old English, the first half-line (the on-verse, or a-verse) was not very different rhythmically from the second half-line (the off-verse, or b-verse). In Middle English, the a-verse had great rhythmic flexibility (so long as it contained two clear strong stresses), whereas the b-verse could only contain one "long dip" (sequence of two or more unstressed or weakly stressed syllables).[85][86] These rules applied to unrhymed alliterative long lines, typical of longer alliterative poems. Rhyming alliterative poems, such as Pearl and the densely structured poem The Three Dead Kings, were generally built, like later English rhyming verse, on patterns of alternating stresses.[87]

The following lines Piers Plowman illustrate the basic rhythmic patterns of the Middle English alliterative long line:

A feir feld full of folk fond I þer bitwene,

Of alle maner of men, þe mene and þe riche,

Worchinge and wandringe as þe world askeþ.

In modern spelling:

A fair field full of folk found I there between,

Of all manner of men the mean and the rich,

Working and wandering as the world asketh.

In modern translation:

Among them I found a fair field full of people

All manner of men, the poor and the rich

Working and wandering as the world requires.

The 'a' verses contain multiple unstressed or weakly stressed syllables before, between, and after the two main stresses. In the 'b' verses, the long dip is always immediately before or after the first strong stress in that half-line.

Rules for Alliteration

In the Middle-English 'a'-verse, the two main stresses alliterate with one another and with the first stressed syllable in the 'b'-verse. There are thus a minimum of three alliterations in the Middle English long line,[88] a fact that is implicitly recognized by the comment made by the parson in the Parson's Prologue in the Canterbury Tales that he did not know how to "rum, ram, ruf, by letter".[89] In the 'a'-verse, additional, secondary stresses can also alliterate, as seen in the line quoted above from Piers Plowman ('a fair field full of folk', with four alliterations in the 'a'-verse), or in Sir Gawain l.2, "the borgh brittened and brent" with three alliterations in the 'a'-verse). However, only the first stress in the 'b'-verse is allowed to alliterate. Middle English alliterative verse obeys the general Germanic rule that the last stress in the line does not alliterate.[90]

The Death of the Alliterative Tradition

After the fifteenth century, alliterative verse became fairly uncommon; possibly the last major poem in the tradition is William Dunbar's Tretis of the Tua Marriit Wemen and the Wedo (c. 1500). By the middle of the sixteenth century, the four-beat alliterative line had completely vanished, at least from the written tradition: the last poem using the form that has survived, Scotish Feilde, was written in or soon after 1515 for the circle of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Earl of Derby in commemoration of the Battle of Flodden.

The Modern Alliterative Revival

J. R. R. Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973), a scholar of Old and Middle English as well as a fantasy author,[91] used alliterative verse extensively in both translations and original poetry; some of his poems are embedded in the text of his fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings. Most of his alliterative verse is in modern English, in a variety of styles.[92] Further, he experimented with alliterative verse based on other traditions, such as the Völsungasaga and Atlakviða, in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrun (2009),[93] and The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son describing the aftermath of the Battle of Maldon (1953).[94][95] His Gothic Bagme Bloma ("Flower of the Trees") uses a trochaic metre, with irregular end-rhymes and irregular alliteration in each line; it was published in the 1936 Songs for the Philologists.[96] He wrote a variety of pieces in Old English, including parts of The Seafarer. A version of these appears in "The Notion Club Papers".[97] His verse translations include some 600 lines of Beowulf.[98]

The 2276-line The Lay of the Children of Húrin (c. 1918–1925), published in the 1985 The Lays of Beleriand, is written in Modern English (with some archaic words) and set to the Beowulf metre. Lines 610-614 run:

'Let the bow of Beleg to your band be joined;

and swearing death to the sons of darkness

let us suage our sorrow and the smart of fate!

Our valour is not vanquished, nor vain the glory

that once we did win in the woods of old.'

C. S. Lewis

Alliterative verse is occasionally written by other modern authors. C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) wrote a narrative poem of 742 lines called The Nameless Isle, published posthumously in Narrative Poems (1972). Lines 562–67 read:

The marble maid, under mask of stone

shook and shuddered. As a shadow streams

Over the wheat waving, over the woman's face

Life came lingering. Nor was it long after

Down its blue pathways, blood returning

Moved, and mounted to her maiden cheek.

W. H. Auden

W. H. Auden (1907–1973) wrote poems including the 1947 The Age of Anxiety in a type of alliterative verse modified for modern English:

Deep in my dark. the dream shines

Yes, of you you dear always;

My cause to cry, cold but my

Story still, still my music.

Mild rose the moon, moving through our

Naked nights: tonight it rains;

Black umbrellas: blossom out;

Gone the gold, my golden ball.

…

Richard Wilbur

Richard Wilbur's Junk opens with the lines:

An axe angles from my neighbor's ashcan;

It is hell's handiwork, the wood not hickory.

The flow of the grain not faithfully followed.

The shivered shaft rises from a shellheap

Of plastic playthings, paper plates.

Other poets who have experimented with modern alliterative English verse include Ezra Pound in his version of The Seafarer, and Alaric Watts, whose famously complex[99] The Siege of Belgrade combines alliteration with both rhymed metre and abecedarian verse. Many translations of Beowulf, in keeping with the source material, use alliteration. Among recent translations, Seamus Heaney's loosely follows the rules of modern alliterative verse, while Alan Sullivan's and Timothy Murphy's follow them more closely.[citation needed]

Old Norse poetic forms

The inherited form of alliterative verse was modified somewhat in Old Norse poetry. In Old Norse, as a result of phonetic changes from the original common Germanic language, many unstressed syllables were lost. This lent Old Norse verse a characteristic terseness; the lifts tended to be crowded together at the expense of the weak syllables. In some lines, the weak syllables have been entirely suppressed. From the Hávamál:

Deyr fé deyja frændr |

Cattle die; kinsmen die... |

The various names of the Old Norse verse forms are given in the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. The Háttatal, or "list of verse forms", contains the names and characteristics of each of the fixed forms of Norse poetry.

Fornyrðislag

A verse form close to that of Beowulf was used on runestones and in the Old Norse Poetic Edda; in Norse, it was called fornyrðislag, which means "old story metre". The Norse poets tended to break up their verses into stanzas of from two to eight lines (or more), rather than writing continuous verse after the Old English model.[b] The loss of unstressed syllables made these verses seem denser and more emphatic. The Norse poets, unlike the Old English poets, tended to make each line a complete syntactic unit, avoiding enjambment where a thought begun on one line continues through the following lines; only seldom do they begin a new sentence in the second half-line. This example is from the Waking of Angantyr:

Vaki, Angantýr! vekr þik Hervǫr, |

Fornyrðislag has two lifts per half line, with two or three (sometimes one) unstressed syllables. At least two lifts, usually three, alliterate, always including the main stave (the first lift of the second half-line). It had a variant form called málaháttr ("speech meter"), which adds an unstressed syllable to each half-line, making six to eight (sometimes up to ten) unstressed syllables per line. Conversely, another variant, kviðuháttr, has only three syllables in its odd half-lines (but four in the even ones).[100]

Ljóðaháttr

Change in form came with the development of ljóðaháttr, which means "song" or "ballad metre", a stanzaic verse form that created four line stanzas. The odd numbered lines were almost standard lines of alliterative verse with four lifts and two or three alliterations, with cæsura; the even numbered lines had three lifts and two alliterations, and no cæsura. This example is from Freyr's lament in Skírnismál:

Lǫng es nótt, lǫng es ǫnnur, |

Long is one night, long is the next; |

A number of variants occurred in ljóðaháttr, including galdralag ("incantation meter"), which adds a fifth short (three-lift) line to the end of the stanza; in this form, usually the fifth line echoes the fourth one.

Dróttkvætt

These verse forms were elaborated even more into the skaldic poetic form called dróttkvætt, meaning "courtly metre",[101] which added internal rhymes and other forms of assonance that go well beyond the requirements of Germanic alliterative verse and greatly resemble the Celtic forms (Irish and Welsh). The dróttkvætt stanza had eight lines, each having usually three lifts and almost invariably six syllables. Although other stress patterns appear, the verse is predominantly trochaic. The last two syllables in each line had to form a trochee[102] (there are a few specific forms which utilize a stressed word at line-end, such as in some docked forms).[103][failed verification] In addition, specific requirements obtained for odd-numbered and even-numbered lines.

In the odd-numbered lines (equivalent to the a-verse of the traditional alliterative line):

- Two of the stressed syllables alliterate with each other.

- Two of the stressed syllables share partial rhyme of consonants (which was called skothending) with dissimilar vowels (e.g. hat and bet), not necessarily at the end of the word (e.g. touching and orchard).

In the even lines (equivalent to the b-verse of the traditional alliterative line):

- The first stressed syllable must alliterate with the alliterative stressed syllables of the previous line.

- Two of the stressed syllables rhyme (aðalhending, e.g. hat and cat), not necessarily at the end of the word (e.g. torching and orchard).

The requirements of the verse form were so demanding that occasionally the text of the poems had to run parallel, with one thread of syntax running through the on-side of the half-lines, and another running through the off-side. According to the Fagrskinna collection of sagas, King Harald III of Norway uttered these lines of dróttkvætt at the Battle of Stamford Bridge; the internal assonances and the alliteration are emboldened:

- Krjúpum vér fyr vápna,

- (valteigs), brǫkun eigi,

- (svá bauð Hildr), at hjaldri,

- (haldorð), í bug skjaldar.

- (Hátt bað mik), þar's mœttusk,

- (menskorð bera forðum),

- hlakkar íss ok hausar,

- (hjalmstall í gný malma).

- In battle, we do not creep behind a shield before the din of weapons (so said the goddess of hawk-land [a valkyrja], true of words). She who wore the necklace bade me to bear my head high in battle, when the battle-ice [a gleaming sword] seeks to shatter skulls.

The bracketed words in the poem ("so said the goddess of hawk-land, true of words") are syntactically separate but interspersed within the text of the rest of the verse. The elaborate kennings manifested here are also practically necessary in this complex and demanding form, as much to solve metrical difficulties as for the sake of vivid imagery. Intriguingly, the saga claims that Harald improvised these lines after he gave a lesser performance (in fornyrðislag); Harald judged that verse bad and then offered this one in the more demanding form. While the exchange may be fictionalized, the scene illustrates the regard in which the form was held.

Most dróttkvætt poems that survive appear in one or another of the Norse sagas; several of the sagas are biographies of skaldic poets.

Hrynhenda

Hrynhenda or hrynjandi háttr ('the flowing verse-form') is a later development of dróttkvætt with eight syllables per line instead of six, with the similar rules of rhyme and alliteration, although each hrynhent-variant shows particular subtleties. It is first attested around 985 in the so-called Hafgerðingadrápa of which four lines survive (alliterants and rhymes bolded):

- Mínar biðk at munka reyni

- meinalausan farar beina;

- heiðis haldi hárar foldar

- hallar dróttinn of mér stalli.

- I ask the tester of monks (God) for a safe journey; the lord of the palace of the high ground (God — here we have a kenning in four parts) keep the seat of the falcon (hand) over me.

The author was said to be a Christian from the Hebrides, who composed the poem asking God to keep him safe at sea. (Note: The third line is, in fact, over-alliterated. There should be exactly two alliterants in the odd-numbered lines.) The metre gained some popularity in courtly poetry, as the rhythm may sound more majestic than dróttkvætt.

We learn much about these in the Hattatal:[104] Snorri gives for certain at least three different variant-forms of hrynhenda. These long-syllabled lines are explained by Snorri as being extra-metrical in most cases: the "main" form never has alliteration or rhyme in the first 2 syllables of the odd-lines (i.e., rhymes always coming at the fourth-syllable), and the even-lines never have rhyme on the fifth/sixth syllables (i.e.: they cannot harbor rhyme in these places because they extra-metrical), the following couplet shows the paradigm:

- Tiggi snýr á ógnar áru

- (Undgagl veit þat) sóknar hagli.

[Note the juxtaposition of alliteration and rhyme of the even-line]

Then, the variant-forms show unsurprising dróttkvætt patterns overall; the main difference being that the first trochee of the odd-lines are technically not reckoned as extrametrical since they harbor alliteration, but the even-lines' extra-metrical feature is more or less as the same. The 2nd form is the "troll-hrynjandi": in the odd-lines the alliteration is moved to the first metrical position (no longer "extra-metrical") while the rhyme remains the same (Snorri seems to imply that frumhending, which is placing a rhyme on the first syllable of any line, is preferably avoided in all these forms: the rhymes are always preferred as oddhending, "middle-of-the-line rhymes") — in the even-lines the rhyme and alliteration are not juxtaposed, and this is a key feature of its distinction (the significant features only are marked in bold below):

- Stála kendi steykvilundum

- Styriar valdi raudu falda....

The next form, which Snorri calls "ordinary/standard hrynhenda", is almost like a "combination" of the previous — alliteration always on the first metrical-position, and the rhymes in the odd-lines juxtaposed (all features in bold in this example):

- Vafdi lítt er virdum mætti

- Vígrækiandi fram at s'ækia.'

There is one more form which is a bit different though seemed to be counted among the previous group by Snorri, called draughent. The syllable-count changes to seven (and, whether relevant to us or not, the second-syllable seems to be counted as the extra-metrical):

- Vápna hríd velta nádi

- Vægdarlaus feigum hausi.

- Hilmir lét höggum mæta

- Herda klett bana verdant.

As one can see, there is very often clashing stress in the middle of the line (Vápna hríd velta....//..Vægdarlaus feigum...., etc.), and oddhending seems preferred (as well as keeping alliterative and rhyming syllables separated, which likely has to do with the syllabic-makeup of the line).

High German and Saxon forms

The Old High German and Old Saxon corpus of Stabreim or alliterative verse is small. Fewer than 200 Old High German lines survive, in four works: the Hildebrandslied, Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms and the Wessobrunn Prayer. All four are preserved in forms that are clearly to some extent corrupt, suggesting that the scribes may themselves not have been entirely familiar with the poetic tradition. Two Old Saxon alliterative poems survive. One is the reworking of the four gospels into the epic Heliand (nearly 6000 lines), where Jesus and his disciples are portrayed in a Saxon warrior culture. The other is the fragmentary Genesis (337 lines in 3 unconnected fragments), created as a reworking of Biblical content based on Latin sources.

However, both German traditions show one common feature which is much less common elsewhere: a proliferation of unaccented syllables. Generally these are parts of speech which would naturally be unstressed — pronouns, prepositions, articles, modal auxiliaries — but in the Old Saxon works there are also adjectives and lexical verbs. The unaccented syllables typically occur before the first stress in the half-line, and most often in the b-verse.

The Hildebrandslied, lines 4–5:

Garutun se iro guðhamun, gurtun sih iro suert ana, |

They prepared their fighting outfits, girded their swords on, |

The Heliand, line 3062:

- Sâlig bist thu Sîmon, quað he, sunu Ionases; ni mahtes thu that selbo gehuggean

- Blessed are you Simon, he said, son of Jonah; for you did not see that yourself (Matthew 16, 17)

This leads to a less dense style, no doubt closer to everyday language, which has been interpreted both as a sign of decadent technique from ill-tutored poets and as an artistic innovation giving scope for additional poetic effects. Either way, it signifies a break with the strict Sievers typology.

In more recent times, Richard Wagner sought to evoke old German models and what he considered a more natural and less over-civilised style by writing his Ring poems in Stabreim.

Relationship with Kalevala meter

The trochaic tetrametrical meter that characterises the traditional poetry of most Finnic-language cultures, known as Kalevala meter, does not deploy alliteration with the structural regularity of Germanic-language alliterative verse, but Kalevala meter does have a very strong convention that, in each line, two lexically stressed syllables should alliterate. In view of the profound influence of the Germanic languages on other aspects of the Finnic languages and the unusualness of such regular requirements for alliteration, it has been argued that Kalevala meter borrowed both its use of alliteration and possibly other metrical features from Germanic.[7]

Notes

- ^ Old Norse poetry is not, traditionally, written in this manner. A half line as described above is written as a whole line in (for example) editions of the Poetic Edda, though scholars such as Andreas Heusler and Eduard Sievers have applied the half-line structure to Eddaic poetry.

- ^ It must be kept in mind, that the Norse poets didn't write, they composed, as did all poets ancient enough for that matter. This "breaking up of lines" was dictated by ear, not pen.

References

- ^ Hogan, Patrick Colm (1997). "Literary Universals". Poetics Today. 18 (2): 223–249. doi:10.2307/1773433. ISSN 0333-5372.

- ^ Goering, N. (2016). The linguistic elements of Old Germanic metre: phonology, metrical theory, and the development of alliterative verse (http://purl.org/dc/dcmitype/Text thesis). University of Oxford.

{{cite thesis}}: External link in|degree= - ^ The Poetic Edda. University of Texas Press. 1962. ISBN 978-0-292-74791-3.

- ^ "Old Saxon alliterative verse", Beowulf and Old Germanic Metre, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136–170, 1998-03-05, retrieved 2023-11-26

- ^ Sommer, Herbert W. (October 1960). "The Muspilli-Apocalypse". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 35 (3): 157–163. doi:10.1080/19306962.1960.11787011. ISSN 0016-8890.

- ^ Cable, Thomas (1991-12-31). The English Alliterative Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-0385-3.

- ^ a b Frog, "The Finnic Tetrameter: A Creolization of Poetic Form?", Studia Metrica et Poetica, 6.1 (2019), 20–78.

- ^ Travis, James (April 1942). "The Relations between Early Celtic and Early Germanic Alliteration". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 17 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1080/19306962.1942.11786083. ISSN 0016-8890.

- ^ Rouse, Robert; Echard, Sian; Fulton, Helen; Rector, Geoff; Fay, Jacqueline Ann, eds. (2017-07-17). The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118396957.wbemlb495. ISBN 978-1-118-39698-8.

- ^ Kara, György (2011), "Alliteration in Mongol Poetry", Alliteration in Culture, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 156–179, ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3, retrieved 2023-11-24

- ^ Orwin, Martin (2011), "Alliteration in Somali Poetry", Alliteration in Culture, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 219–230, ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3, retrieved 2023-11-24

- ^ Frog (2019-08-29). "The Finnic Tetrameter – A Creolization of Poetic Form?". Studia Metrica et Poetica. 6 (1): 20–78. doi:10.12697/smp.2019.6.1.02. ISSN 2346-691X.

- ^ Gupta, Rahul (2014). "The Tale of the Tribe": The Twentieth-Century Alliterative Revival, pp. 7-8 (phd thesis). University of York.

- ^ Adalsteinsson, Ragnar Ingi (2014). Traditions and Continuities: Alliteration in Old and Modern Icelandic Verse. University of Iceland Press. ISBN 978-9935-23-036-2.

- ^ Ross, Margaret Clunies (2005). A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-279-8.

- ^ Vésteinn Ólason, 'Old Icelandic Poetry', in A History of Icelandic Literature, ed. by Daisy Nejmann, Histories of Scandinavian Literature, 5 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), pp. 1-63 (pp. 55-59).

- ^ "Rímur EP (2001) - Sigur Rós with Steindór Andersen - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Jónas Hallgrímsson: Selected Poetry and Prose". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ Árnason, Kristján (2011), Roper, Jonathan (ed.), "Alliteration in Iceland: From the Edda to Modern Verse and Pop Lyrics", Alliteration in Culture, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 123–140, doi:10.1057/9780230305878_9, ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3, retrieved 2023-11-26

- ^ Wilson, William A. (1975). "The "Kalevala" and Finnish Politics". Journal of the Folklore Institute. 12 (2/3): 131–155. doi:10.2307/3813922. ISSN 0015-5934.

- ^ Simonsuuri, Kirsti (1989). "From Orality to Modernity: Aspects of Finnish Poetry in the Twentieth Century". World Literature Today. 63 (1): 52. doi:10.2307/40145048. ISSN 0196-3570.

- ^ Alhoniemi, Pirkko; Binham, Philip (1985). "Modern Finnish Literature from Kalevala and Kanteletar Sources". World Literature Today. 59 (2): 229. doi:10.2307/40141460. ISSN 0196-3570.

- ^ Doesburg, Charlotte (2021-06-01). "Of heroes, maidens and squirrels: Reimagining traditional Finnish folk poetry in metal lyrics". Metal Music Studies. 7 (2): 317–333. doi:10.1386/mms_00051_1. ISSN 2052-3998.

- ^ Wise, Dennis Wilson (2021). "Poul Anderson and the American Alliterative Revival". Extrapolation. 62 (2): 157–180. doi:10.3828/extr.2021.9. ISSN 0014-5483.

- ^ a b Wilson Wise, Dennis (2021). "Antiquarianism Underground: The Twentieth-century Alliterative Revival in American Genre Poetry". Studies in the Fantastic. 11 (1): 22–54. doi:10.1353/sif.2021.0001. ISSN 2470-3486.

- ^ "Published Authors of Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Styles and Themes: Trends in Modern Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ a b Wise, Dennis, ed. (2023-12-15). Speculative Poetry and the Modern Alliterative Revival: A Critical Anthology. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1-68393-329-8.

- ^ "The Speculative Fiction Community". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "The Society for Creative Anachronism: Sponsors of Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "Collections: Anthologies that Contain Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "Reconstructing an oral tradition: Problems in the comparative metrical analysis of Old English, Old Saxon and Old Norse alliterative verse - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ Pascual, Rafael J. (2017-07-03). "Oral Tradition and the History of English Alliterative Verse". Studia Neophilologica. 89 (2): 250–260. doi:10.1080/00393274.2017.1369360. ISSN 0039-3274.

- ^ "Reconstructing an oral tradition: Problems in the comparative metrical analysis of Old English, Old Saxon and Old Norse alliterative verse - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Doane, Alger Nicolaus; Pasternack, Carol Braun (1991). Vox Intexta: Orality and Textuality in the Middle Ages. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-13094-7.

- ^ Wanner, Kevin J. (2008-01-01). Snorri Sturluson and the Edda: The Conversion of Cultural Capital in Medieval Scandinavia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9801-6.

- ^ Orchard, Andy (2003). A Critical Companion to Beowulf. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84384-029-9.

- ^ "Snorri Sturluson and "Beowulf" - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Price, T. Douglas (2015-06-12). Ancient Scandinavia: An Archaeological History from the First Humans to the Vikings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-023198-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Terasawa 2011, pp. 3–26 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTerasawa2011 (help)

- ^ Gade, Kari Ellen (1995). The Structure of Old Norse Dróttkvætt Poetry. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3023-7.

- ^ Carroll, Benjamin H. (June 1996). "Old English Prosody". Journal of English Linguistics. 24 (2): 93–115. doi:10.1177/007542429602400203. ISSN 0075-4242.

- ^ Terasawa 2011, pp. 31–33 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFTerasawa2011 (help)

- ^ Turville-Petre, Thorlac (2010). "<i>Approaches to the Metres of Alliterative Verse</i> (review)". JEGP, Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 109 (2): 240–242. doi:10.1353/egp.0.0144. ISSN 1945-662X.

- ^ Minkova, Donka (2020-11-09), "4. First or best, last not least: Domain edges in the history of English", Studies in the History of the English Language VIII, De Gruyter, pp. 109–134, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ a b Minkova 2003, ch. 4

- ^ Minkova 2003, chs. 5-7

- ^ Cronan, Dennis (December 2004). "Poetic words, conservatism and the dating of Old English poetry". Anglo-Saxon England. 33: 23–50. doi:10.1017/s026367510400002x. ISSN 0263-6751.

- ^ Ross, Margaret Clunies (2005). A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-279-8.

- ^ Scholtz, Hendrik van der Merwe (1927). The Kenning in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse Poetry. N. V. Dekker & Van de Vegt en J. W. Van Leeuwen.

- ^ Fulk, Robert D. (2021-04-01). "Kennings in Old English Verse and in the Poetic Edda". European Journal of Scandinavian Studies. 51 (1): 69–91. doi:10.1515/ejss-2020-2030. ISSN 2191-9402.

- ^ Birgisson, Bergsveinn (2010-01-01), "The Old Norse Kenning As A Mnemonic Figure", The Making of Memory in the Middle Ages, BRILL, pp. 199–213, ISBN 978-90-474-4160-1, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ 'fit | fytte, n.1.', Oxford English Dictionary Online, 1st edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1896).

- ^ R. D. Fulk, 'The Origin of the Numbered Sections in Beowulf and in Other Old English Poems', Anglo-Saxon England, 35 (2006), 91-109 (p. 91 fn. 1).

- ^ "Old Saxon alliterative verse", Beowulf and Old Germanic Metre, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136–170, 1998-03-05, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983) [1940]. On Translating Beowulf. George Allen and Unwin.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Cherniss, Michael D. (1972). Ingeld and Christ: Heroic concepts and values in old English Christian poetry. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

- ^ Ghosh, Shami (2016-01-01), "Looking Back to a Troubled Past: Beowulf and Anglo-Saxon Historical Consciousness", Writing the Barbarian Past: Studies in Early Medieval Historical Narrative, BRILL, pp. 184–221, ISBN 978-90-04-30522-9, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Abram, Christopher (2007-07-18). "Aldhelm and the Two Cultures of Anglo‐Saxon Poetry". Literature Compass. 4 (5): 1354–1377. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2007.00483.x. ISSN 1741-4113.

- ^ Fulk, R. D.; Cain, Christopher M., eds. (2013-03-18). A History of Old English Literature. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-45323-0.

- ^ A. J. Bliss, ‘Single Half-Lines in Old English Poetry’, Notes and Queries 18.12 (1971), 442–49.

- ^ John Miles Foley, ‘Hybrid Prosody and Single Half-Lines in Old English and Serbo-Croatian Poetry’, Neophilologus 64.2 (1980), 284–89.

- ^ Terasawa, Jun (2011). Old English Metre: An Introduction. University of Toronto Press. p. 60.

- ^ Russom, Geoffrey (2007-05-18), "Evolution of the a-verse in English alliterative meter", Studies in the History of the English Language III, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 63–88, ISBN 978-3-11-019089-2, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Lester, G. A. (1996), "Old English Poetic Diction", The Language of Old and Middle English Poetry, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 47–66, ISBN 978-0-333-48847-8, retrieved 2023-12-01

- ^ Hill, Archibald A.; Lind, L. R. (1953). "Studies in Honor of Albert Morey Sturtevant". Language. 29 (4): 547. doi:10.2307/409975. ISSN 0097-8507.

- ^ Cornelius, Ian (2012). "Review Essay: Alliterative Revival: Retrospect and Prospect". The Yearbook of Langland Studies. 26: 261–276. doi:10.1484/J.YLS.1.103211. ISSN 0890-2917.

- ^ Salter, Elizabeth (1978). "Review of The Alliterative Revival". The Review of English Studies. 29 (116): 462–464. ISSN 0034-6551.

- ^ Feulner, Anna Helene (2019-11-11). "Eric Weiskott. 2016. English Alliterative Verse: Poetic Tradition and Literary History. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature 96. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, xiv + 236 pp., 6 figures, £ 64.99". Anglia. 137 (4): 670–678. doi:10.1515/ang-2019-0060. ISSN 1865-8938.

- ^ Brehe, S. K. (2000). "Rhyme and the Alliterative Standard in LaƷamon's Brut". Parergon. 18 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1353/pgn.2000.0004. ISSN 1832-8334.

- ^ Weiskott, Eric (2016). English Alliterative Verse. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Prior, Sandra Pierson (2012-01-01). The Fayre Formez of the Pearl Poet. MSU Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-945-1.

- ^ ALFORD, JOHN A., ed. (2023-04-28). A Companion to Piers Plowman. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90831-4.

- ^ Pearsall, Derek; Burrow, J. A. (1986). "Medieval Writers and Their Work: Middle English Literature and Its Background 1100-1500". The Modern Language Review. 81 (1): 164. doi:10.2307/3728781. ISSN 0026-7937.

- ^ Weiskott, Eric (2016). English Alliterative Verse. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Cooper, Helen; Edwards, Robert R., eds. (2023-05-18). The Oxford History of Poetry in English. Oxford University PressOxford. ISBN 0-19-882742-3.

- ^ KOSSICK, SHIRLEY (1979). "EPIC AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH ALLITERATIVE REVIVAL". English Studies in Africa. 22 (2): 71–82. doi:10.1080/00138397908690761. ISSN 0013-8398.

- ^ Moran, Patrick (2017-06-26), "Text-Types and Formal Features", Handbook of Arthurian Romance, De Gruyter, pp. 59–78, ISBN 978-3-11-043246-6, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Weiskott, Eric (2019). "Political Prophecy and the Form of Piers Plowman". Viator. 50 (1): 207–247. doi:10.1484/j.viator.5.121362. ISSN 0083-5897.

- ^ "Piers Plowman and Other Alliterative Poems", THE MIDDLE AGES, Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis, pp. 240–248, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Duggan, Hoyt N. (1977). "Strophic Patterns in Middle English Alliterative Poetry". Modern Philology. 74 (3): 223–247. doi:10.1086/390723. ISSN 0026-8232.

- ^ Weiskott, Eric (2021). Meter and Modernity in English Verse, 1350-1650. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ "Medieval Institute Publications | Western Michigan University Research | ScholarWorks at WMU". scholarworks.wmich.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ Eric, Weiskott (9 November 2016). English Alliterative Verse: Poetic Tradition and Literary History. Cambridge. ISBN 978-1316718674. OCLC 968234809.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ Cable, Thomas (2009). "Progress in Middle English Alliterative Metrics". The Yearbook of Langland Studies. 23: 243–264. doi:10.1484/J.YLS.1.100478. ISSN 0890-2917.

- ^ Inoue, Noriko; Stokes, Myra (2012). "Restrictions on Dip Length in the Alliterative Line: The A-Verse and the B-Verse". The Yearbook of Langland Studies. 26: 231–260. doi:10.1484/J.YLS.1.103210. ISSN 0890-2917.

- ^ Cole, Kristin Lynn (2007). Rum, ram, ruf, and rym: Middle English alliterative meters. The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ Cable, Thomas (1991-12-31). The English Alliterative Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-0385-3.

- ^ Sutherland, A. (2004-11-01). "Review: Alliterative Revivals". The Review of English Studies. 55 (222): 787–788. doi:10.1093/res/55.222.787. ISSN 0034-6551.

- ^ Duggan, Hoyt N. (1977). "Strophic Patterns in Middle English Alliterative Poetry". Modern Philology. 74 (3): 223–247. doi:10.1086/390723. ISSN 0026-8232.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 111, 200, 266 and throughout. ISBN 978-0-04928-037-3.

- ^ Smol, Anna; Foster, Rebecca (2021). "J.R.R. Tolkien's 'Homecoming' and Modern Alliterative Metre". Journal of Tolkien Research. 12 (1). Article 3.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R.; Tolkien, Christopher (2009). The legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-27342-6. OCLC 310224953.

- ^ Clark, George (2000). George Clark and Daniel Timmons (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 39–51.

- ^ Shippey, Tom A. (2007). Roots and Branches: Selected Papers on Tolkien. Zurich and Berne: Walking Tree Publishers. pp. 323–339.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. Songs for the Philologists. Privately printed in the Department of English, University College London, 1936.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1992). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Sauron Defeated. Boston, New York, & London: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-60649-7., "The Notion Club Papers"

- ^ Acocella, Joan (2 June 2014). "Slaying Monsters: Tolkien's 'Beowulf'". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Myers, Jack; Simms, Michael (1985). Longman Dictionary and Handbook of Poetry. New York and London: Longman. ISBN 0582283434.

0582283434.

- ^ Poole, Russell. 2005. Metre and Metrics. In: McTurk, Rory (ed.). A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature. P.267-268

- ^ Clunies Ross 2005, p. 21.

- ^ Clunies Ross 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Ringler, Dick (ed. and trans.). Jónas Hallgrímsson: Selected Poetry and Prose (1998), ch. III.1.B 'Skaldic Strophes', http://www.library.wisc.edu/etext/jonas/Prosody/Prosody-I.html#Pro.I.B Archived 2013-01-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hattatal, Snorri Sturluson

Sources

- Clunies Ross, Margaret (2005). A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics. D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1843842798.

- Minkova, Donka (2003). Alliteration and Sound Change in Early English. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, 101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521573177.

- Terasawa, Jun (2011). Old English Metre: An Introduction. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442611290.

Further reading

- Bostock, J. K. (1976). "Appendix on Old Saxon and Old High German Metre". In K.C.King; D.R.McLintock (eds.). A Handbook on Old High German Literature. Oxford University Press.

- Cable, Thomas (1991). The English Alliterative Tradition. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812230635.

- Fulk, Robert D. (1992). A History of Old English Meter. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Godden, Malcolm R. (1992). "Literary Language". In Hogg, Richard M. (ed.). The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 490–535.

- Russom, Geoffrey (1998). Beowulf and Old Germanic Metre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521593403.

- Sievers, Eduard (1893). Altgermanische Metrik. Niemeyer.

- Terasawa, Jun (2011). Old English Metre: An Introduction. University of Toronto Press.

- Weiskott, Eric (2016). English Alliterative Verse: Poetic Tradition and Literary History. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Carmina Scaldica a selection of Norse and Icelandic skaldic poetry, ed. Finnur Jónsson, 1929

- Jörmungrund An extensive resource for Old Norse poetry

- Jónas Hallgrímsson: Selected Poetry and Prose, ed. and trans. by Dick Ringler (1998), ch. 3 Probably the most accessible discussion in English of alliterant placement in modern Icelandic (also mostly applicable to Old Norse).

- Forgotten ground regained A site dedicated to alliterative and accentual poetry.

- An interactive guide to Old and Middle English alliterative verse by Alaric Hall.