Timeline of volcanism on Earth: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m Citations: [215] added: author, last1, postscript. Tweaked: doi, issue. Unified citation types. Rjwilmsi |

||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

|url= |

|url= |

||

|accessdate= |

|accessdate= |

||

|doi = }}</ref> |

|doi =10.1130/0016-7606(2007)119[1283:AAFSOQ]2.0.CO;2 }}</ref> |

||

*[[Sutter Buttes]], [[Central Valley of California]], USA; were formed over 1.5 Ma by a now-extinct volcano. |

*[[Sutter Buttes]], [[Central Valley of California]], USA; were formed over 1.5 Ma by a now-extinct volcano. |

||

*Ebisutoge-Fukuda tephras, Japan; 1.75 Ma; {{convert|380|to|490|km3|cumi|1|sp=us}} of tephra.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

*Ebisutoge-Fukuda tephras, Japan; 1.75 Ma; {{convert|380|to|490|km3|cumi|1|sp=us}} of tephra.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

||

| Line 251: | Line 251: | ||

*[[Pastos Grandes Caldera]] (size: 40 x 50 km), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, Bolivia; 2.9 Ma; VEI 7; more than {{convert|820|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Pastos Grandes [[Ignimbrite]].<ref>Ort, M. H.; de Silva, S.; Jiminez, N.; Salisbury, M.; Jicha, B. R. and Singer, B. S. (2009). [http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2009AM/finalprogram/abstract_165247.htm Two new supereruptions in the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex of the Central Andes].</ref> |

*[[Pastos Grandes Caldera]] (size: 40 x 50 km), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, Bolivia; 2.9 Ma; VEI 7; more than {{convert|820|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Pastos Grandes [[Ignimbrite]].<ref>Ort, M. H.; de Silva, S.; Jiminez, N.; Salisbury, M.; Jicha, B. R. and Singer, B. S. (2009). [http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2009AM/finalprogram/abstract_165247.htm Two new supereruptions in the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex of the Central Andes].</ref> |

||

*[[Little Barrier Island]], northeastern coast of [[New Zealand]]'s [[North Island]]; it erupted from 1 million to 3 Ma.<ref> |

*[[Little Barrier Island]], northeastern coast of [[New Zealand]]'s [[North Island]]; it erupted from 1 million to 3 Ma.<ref> |

||

{{cite journal |last=Lindsay |first=Jan M. |coauthors=Tim J. Worthington, Ian E. M. Smith, and Philippa M. Black |year=1999 |month=June |title=Geology, petrology, and petrogenesis of Little Barrier Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand |journal=New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics |volume=42 |issue=2 |pages=155–168 |url=http://www.rsnz.org/publish/nzjgg/1999/11.pdf |accessdate= 2007-12-03}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}<!--This paper does not mention any VEI-6 eruptions. The entire current edifice has a volume of about 13 km³. It is ok, before the Quartenary there is no claim that it is VEI-6 or equivalent --> |

{{cite journal |doi=10.1080/00288306.1999.9514837 |last=Lindsay |first=Jan M. |coauthors=Tim J. Worthington, Ian E. M. Smith, and Philippa M. Black |year=1999 |month=June |title=Geology, petrology, and petrogenesis of Little Barrier Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand |journal=New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics |volume=42 |issue=2 |pages=155–168 |url=http://www.rsnz.org/publish/nzjgg/1999/11.pdf |accessdate= 2007-12-03}} {{Dead link|date=October 2010|bot=H3llBot}}<!--This paper does not mention any VEI-6 eruptions. The entire current edifice has a volume of about 13 km³. It is ok, before the Quartenary there is no claim that it is VEI-6 or equivalent --> |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

*[[Mount Kenya]]; a [[stratovolcano]] created approximately 3 Ma after the opening of the [[East African rift]].<ref name=Rift>{{Cite web |

*[[Mount Kenya]]; a [[stratovolcano]] created approximately 3 Ma after the opening of the [[East African rift]].<ref name=Rift>{{Cite web |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

| publisher = Teton Tectonics |

| publisher = Teton Tectonics |

||

| accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref><ref name=Heise>{{cite journal|last= |

| accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref><ref name=Heise>{{cite journal|last= |

||

|last1= |

|||

|first= Lisa A. Morgan |

Morgan|first= Lisa A. Morgan |

||

|coauthors= William C. McIntosh |

|coauthors= William C. McIntosh |

||

|date= March 2005 |

|date= March 2005 |

||

| Line 316: | Line 317: | ||

|url= http://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/106/10/1304 |

|url= http://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/106/10/1304 |

||

|accessdate= 2010-03-26 |

|accessdate= 2010-03-26 |

||

|doi = }}</ref> |

|doi =10.1130/0016-7606(1994)106<1304:ECVITM>2.3.CO;2 }}</ref> |

||

**[[Campi Flegrei]], Naples, Italy; 14.9 Ma; {{convert|79|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Neapolitan Yellow Tuff.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

**[[Campi Flegrei]], Naples, Italy; 14.9 Ma; {{convert|79|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Neapolitan Yellow Tuff.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

||

**Huaylillas Ignimbrite, Bolivia, southern Peru, northern Chile; 15 Ma ±1; {{convert|1100|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of tephra.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

**Huaylillas Ignimbrite, Bolivia, southern Peru, northern Chile; 15 Ma ±1; {{convert|1100|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of tephra.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

||

| Line 356: | Line 357: | ||

| url= http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1984/JB089iB10p08616.shtml |

| url= http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1984/JB089iB10p08616.shtml |

||

| accessdate= 2010-03-23 |

| accessdate= 2010-03-23 |

||

| doi = }}</ref> |

| doi =10.1029/JB089iB10p08616 }}</ref> |

||

**Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Washburn Caldera, (size: 30 x 25 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 16.548 Ma; {{convert|250|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Oregon Canyon Tuff.<ref name=wardtable2009 /><ref name=lipman1984 /><ref name=ludington1996>{{ |

**Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Washburn Caldera, (size: 30 x 25 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 16.548 Ma; {{convert|250|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Oregon Canyon Tuff.<ref name=wardtable2009 /><ref name=lipman1984 /><ref name=ludington1996>{{Cite document |

||

| |

| author = Steve Ludington, Dennis P. Cox, Kenneth W. Leonard, and Barry C. Moring | contribution = Chapter 5, Cenozoic Volcanic Geology in Nevada | editors = Donald A. Singer | title = An Analysis of Nevada's Metal-Bearing Mineral Resources | volume = | pages = | publisher = Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada | place = | year = 1996 | contribution-url = http://www.nbmg.unr.edu/dox/ofr962/ |

||

| accessdate = 2010-03-23 | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}</ref> |

|||

| accessdate = 2010-03-23}}</ref> |

|||

**Yellowstone hotspot (?), Northwest Nevada volcanic field (NWNV), Virgin Valley, High Rock, Hog Ranch, and unnamed calderas; West of [[Pine Forest Range]], Nevada; 15.5 to 16.5 Ma.<ref>{{cite book |

**Yellowstone hotspot (?), Northwest Nevada volcanic field (NWNV), Virgin Valley, High Rock, Hog Ranch, and unnamed calderas; West of [[Pine Forest Range]], Nevada; 15.5 to 16.5 Ma.<ref>{{cite book |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| year= 2008 |

| year= 2008 |

||

| title= New geologic evidence for additional 16.5-15.5 Ma silicic calderas in northwest Nevada related to initial impingement of the Yellowstone hot spot |

| title= New geologic evidence for additional 16.5-15.5 Ma silicic calderas in northwest Nevada related to initial impingement of the Yellowstone hot spot |

||

| Line 369: | Line 369: | ||

| url= http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/1755-1315/3/1/012002/ees8_3_012002.pdf?request-id=fbb453bc-6e79-4194-965a-0d2abf488999 |

| url= http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/1755-1315/3/1/012002/ees8_3_012002.pdf?request-id=fbb453bc-6e79-4194-965a-0d2abf488999 |

||

| accessdate= 2010-03-23 |

| accessdate= 2010-03-23 |

||

| doi = 10.1088/1755-1307/3/1/012002 |

| doi = 10.1088/1755-1307/3/1/012002 |

||

| ⚫ | |||

**Yellowstone hotspot, Steens and [[Columbia River Basalt Group|Columbia River flood basalts]], Pueblo, Steens, and Malheur Gorge-region, [[Pueblo Mountains]], [[Steens Mountain]], Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, USA; most vigorous eruptions were from 14–17 Ma; {{convert|180000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of lava.<ref name=wardtable2009 /><ref name="Carson">{{cite book|author=Carson, Robert J. and Pogue, Kevin R.|title=Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods:Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington |publisher=Washington State Department of Natural Resources (Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information Circular 90)|year=1996|id=ISBN none}}</ref><ref name="Reidel">{{cite book|author=Reidel, Stephen P.|title=A Lava Flow without a Source: The Cohasset Flow and Its Compositional Members |publisher=The Journal of Geology, Volume 113, Pp 1 - 21 |month=January | year=2005|id=ISBN none}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last= Brueseke |first= M.E. |coauthors= Heizler, M.T., Hart, W.K., and S.A. Mertzman |date= 15 March 2007 |title= Distribution and geochronology of Oregon Plateau (U.S.A.) flood basalt volcanism: The Steens Basalt revisited |journal= Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research |volume= 161 |issue= 3 |pages= 187–214 |url= |accessdate= |

**Yellowstone hotspot, Steens and [[Columbia River Basalt Group|Columbia River flood basalts]], Pueblo, Steens, and Malheur Gorge-region, [[Pueblo Mountains]], [[Steens Mountain]], Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, USA; most vigorous eruptions were from 14–17 Ma; {{convert|180000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of lava.<ref name=wardtable2009 /><ref name="Carson">{{cite book|author=Carson, Robert J. and Pogue, Kevin R.|title=Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods:Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington |publisher=Washington State Department of Natural Resources (Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information Circular 90)|year=1996|id=ISBN none}}</ref><ref name="Reidel">{{cite book|author=Reidel, Stephen P.|title=A Lava Flow without a Source: The Cohasset Flow and Its Compositional Members |publisher=The Journal of Geology, Volume 113, Pp 1 - 21 |month=January | year=2005|id=ISBN none}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last= Brueseke |first= M.E. |coauthors= Heizler, M.T., Hart, W.K., and S.A. Mertzman |date= 15 March 2007 |title= Distribution and geochronology of Oregon Plateau (U.S.A.) flood basalt volcanism: The Steens Basalt revisited |journal= Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research |volume= 161 |issue= 3 |pages= 187–214 |url= |accessdate= |

||

|doi = 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.12.004 }}</ref><ref>[http://www.summitpost.org/area/range/355999/southeast-oregon-basin-and-range.html SummitPost.org, ''Southeast Oregon Basin and Range'']</ref><ref>[http://tin.er.usgs.gov/geology/state/sgmc-unit.php?unit=ORTbas%3B0 USGS, ''Andesitic and basaltic rocks on Steens Mountain'']</ref><ref name=malheurrivergorge >[http://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/115/1/105 GeoScienceWorld, ''Genesis of flood basalts and Basin and Range volcanic rocks from Steens Mountain to the Malheur River Gorge, Oregon'']</ref><ref> |

|doi = 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.12.004 }}</ref><ref>[http://www.summitpost.org/area/range/355999/southeast-oregon-basin-and-range.html SummitPost.org, ''Southeast Oregon Basin and Range'']</ref><ref>[http://tin.er.usgs.gov/geology/state/sgmc-unit.php?unit=ORTbas%3B0 USGS, ''Andesitic and basaltic rocks on Steens Mountain'']</ref><ref name=malheurrivergorge >[http://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/115/1/105 GeoScienceWorld, ''Genesis of flood basalts and Basin and Range volcanic rocks from Steens Mountain to the Malheur River Gorge, Oregon'']</ref><ref> |

||

| Line 454: | Line 455: | ||

*Approximately 23,030,000 years BP, the [[Neogene]] period and the [[Miocene]] epoch begins. |

*Approximately 23,030,000 years BP, the [[Neogene]] period and the [[Miocene]] epoch begins. |

||

**[[La Garita Caldera]] (size: 100 x 35 km), Wheeler Geologic Area, Central Colorado volcanic field, Colorado, USA; VEI 8; {{convert|5000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Fish Canyon Tuff was blasted out in a major single eruption about 27.8 Ma.<ref name=mason2004 /><ref>[http://staff.aist.go.jp/s-takarada/CEV/newsletter/lagarita.html Largest explosive eruptions: New results for the 27.8 Ma Fish Canyon Tuff and the La Garita caldera, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado]</ref><ref>{{cite journal |

**[[La Garita Caldera]] (size: 100 x 35 km), Wheeler Geologic Area, Central Colorado volcanic field, Colorado, USA; VEI 8; {{convert|5000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Fish Canyon Tuff was blasted out in a major single eruption about 27.8 Ma.<ref name=mason2004 /><ref>[http://staff.aist.go.jp/s-takarada/CEV/newsletter/lagarita.html Largest explosive eruptions: New results for the 27.8 Ma Fish Canyon Tuff and the La Garita caldera, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado]</ref><ref>{{cite journal |

||

| doi = 10.1093/petrology/43.8.1469 |

|||

| author = Olivier Bachmann | coauthors = Michael A. Dungan, and Peter W. Lipman | year = 2002 | title = The Fish Canyon Magma Body, San Juan Volcanic Field, Colorado: Rejuvenation and Eruption of an Upper-Crustal Batholith | journal = Journal of Petrology | volume = 43 | issue = 8 | pages = 1469–1503 | url = http://petrology.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/43/8/1469 | accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref> |

| author = Olivier Bachmann | coauthors = Michael A. Dungan, and Peter W. Lipman | year = 2002 | title = The Fish Canyon Magma Body, San Juan Volcanic Field, Colorado: Rejuvenation and Eruption of an Upper-Crustal Batholith | journal = Journal of Petrology | volume = 43 | issue = 8 | pages = 1469–1503 | url = http://petrology.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/43/8/1469 | accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref> |

||

**Unknown source, [[Ethiopia]]; 29 Ma ±1; {{convert|3000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Green Tuff and SAM.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

**Unknown source, [[Ethiopia]]; 29 Ma ±1; {{convert|3000|km3|cumi|0|sp=us}} of Green Tuff and SAM.<ref name=wardtable2009 /> |

||

| Line 490: | Line 492: | ||

| publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

| publisher = Los Alamos National Laboratory |

||

| accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref> It is aligned as a Crater Flat volcanic field, [[Reveille Range|Réveille Range]], [[Lunar Crater National Natural Landmark|Lunar Crater volcanic field]], Zone (CFLC).<ref>{{cite journal |

| accessdate = 2010-03-16 }}</ref> It is aligned as a Crater Flat volcanic field, [[Reveille Range|Réveille Range]], [[Lunar Crater National Natural Landmark|Lunar Crater volcanic field]], Zone (CFLC).<ref>{{cite journal |

||

| |

|author= Smith, E.I., and D.L. Keenan |date= 30 August 2005 |title= Yucca Mountain Could Face Greater Volcanic Threat |journal= Eos, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union |volume= 86 |issue= 35 |pages= |url= http://www.state.nv.us/nucwaste/news2005/pdf/eos20050830.pdf |accessdate= 1/3/09 |doi = }}</ref> The [[Marysvale Volcanic Field]], southwestern Utah is nearby too. |

||

*McDermitt volcanic field, or Orevada rift volcanic field, Nevada/ Oregon, nearby are: [[McDermitt, Nevada-Oregon|McDermitt]], [[Trout Creek Mountains]], [[Bilk Creek Mountains]], [[Steens Mountain]], Jordan Meadow Mountain (6,816 ft), Long Ridge, Trout Creek, and Whitehorse Creek. |

*McDermitt volcanic field, or Orevada rift volcanic field, Nevada/ Oregon, nearby are: [[McDermitt, Nevada-Oregon|McDermitt]], [[Trout Creek Mountains]], [[Bilk Creek Mountains]], [[Steens Mountain]], Jordan Meadow Mountain (6,816 ft), Long Ridge, Trout Creek, and Whitehorse Creek. |

||

*Emmons Lake stratovolcano (caldera size: 11 x 18 km), Aleutian Range, was formed through six eruptions. [[Mount Emmons (Alaska)|Mount Emmons]], Mount Hague, and Double Crater are post-caldera cones.<ref name="largeeruptions"/> |

*Emmons Lake stratovolcano (caldera size: 11 x 18 km), Aleutian Range, was formed through six eruptions. [[Mount Emmons (Alaska)|Mount Emmons]], Mount Hague, and Double Crater are post-caldera cones.<ref name="largeeruptions"/> |

||

*The topography of the [[Basin and Range Province]] is a result of crustal [[extension (geology)|extension]] within this part of the [[North American Plate]] ([[rifting]] of the [[North American craton]] or Laurentia from Western North America; e.g. [[Gulf of California]], [[Rio Grande rift]], Oregon-Idaho [[graben]]). The crust here has been stretched up to 100% of its original width.<ref>[http://geomaps.wr.usgs.gov/parks/province/basinrange.html Geologic Provinces of the United States: Basin and Range Province on USGS.gov website] Retrieved 9 November 2009</ref> In fact, the crust underneath the Basin and Range, especially under the [[Great Basin]] (includes [[Nevada]]), is some of the thinnest in the world. |

*The topography of the [[Basin and Range Province]] is a result of crustal [[extension (geology)|extension]] within this part of the [[North American Plate]] ([[rifting]] of the [[North American craton]] or Laurentia from Western North America; e.g. [[Gulf of California]], [[Rio Grande rift]], Oregon-Idaho [[graben]]). The crust here has been stretched up to 100% of its original width.<ref>[http://geomaps.wr.usgs.gov/parks/province/basinrange.html Geologic Provinces of the United States: Basin and Range Province on USGS.gov website] Retrieved 9 November 2009</ref> In fact, the crust underneath the Basin and Range, especially under the [[Great Basin]] (includes [[Nevada]]), is some of the thinnest in the world. |

||

*Topographically visible calderas: South part of the McDermitt volcanic field (four overlapping and nested calderas), West of [[McDermitt, Nevada-Oregon|McDermitt]]; Cochetopa Park Caldera, West of the [[North Pass]]; [[Henry's Fork Caldera]]; [[Banks Peninsula]], New Zealand ([[:image:Banks Peninsula from space.jpg|Photo]]) and [[Valles Caldera]]. Newer drawings show McDermitt volcanic field (South), as five overlapping and nested calderas. Hoppin Peaks Caldera is included too. |

*Topographically visible calderas: South part of the McDermitt volcanic field (four overlapping and nested calderas), West of [[McDermitt, Nevada-Oregon|McDermitt]]; Cochetopa Park Caldera, West of the [[North Pass]]; [[Henry's Fork Caldera]]; [[Banks Peninsula]], New Zealand ([[:image:Banks Peninsula from space.jpg|Photo]]) and [[Valles Caldera]]. Newer drawings show McDermitt volcanic field (South), as five overlapping and nested calderas. Hoppin Peaks Caldera is included too. |

||

*Repose periods: [[Lake Toba|Toba]] (0.38 Ma),<ref name=chesner1991>{{cite journal|url=http://www.geo.mtu.edu/~raman/papers/ChesnerGeology.pdf|last1=Chesner| first1=C.A.|last2=Westgate|first2=J.A.|last3=Rose|first3=W.I.|last4=Drake|first4=R.|last5=Deino|first5=A.|title=Eruptive History of Earth's Largest Quaternary caldera (Toba, Indonesia) Clarified|volume=19|pages=200–203|journal=Geology|month=March | year=1991|accessdate=2010-01-20}}</ref> [[Valles Caldera]] (0.35 Ma),<ref>Doell, R.R., Dalrymple, G.B., Smith, R.L., and Bailey, R.A., 1986, Paleomagnetism, potassium-argon ages, and geology of rhyolite and associated rocks of the Valles Caldera, New Mexico: Geological Society of America Memoir 116, p. 211-248.</ref><ref>Izett, G.A., Obradovich, J.D., Naeser, C.W., and Cebula, G.T., 1981, Potassium-argon and fission-track ages of Cerro Toledo rhyolite tephra in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico, in Shorter contributions to isotope research in the western United States: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1199-D, p. 37-43.</ref> [[Yellowstone Caldera]] (0.7 Ma).<ref>Christiansen, R.L., and Blank, H.R., 1972, Volcanic stratigraphy of the Quaternary rhyolite plateau in Yellowstone National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 729-B, p. 18.</ref> |

*Repose periods: [[Lake Toba|Toba]] (0.38 Ma),<ref name=chesner1991>{{cite journal|doi=10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0200:EHOESL>2.3.CO;2|url=http://www.geo.mtu.edu/~raman/papers/ChesnerGeology.pdf|last1=Chesner| first1=C.A.|last2=Westgate|first2=J.A.|last3=Rose|first3=W.I.|last4=Drake|first4=R.|last5=Deino|first5=A.|title=Eruptive History of Earth's Largest Quaternary caldera (Toba, Indonesia) Clarified|volume=19|pages=200–203|journal=Geology|month=March | year=1991|accessdate=2010-01-20}}</ref> [[Valles Caldera]] (0.35 Ma),<ref>Doell, R.R., Dalrymple, G.B., Smith, R.L., and Bailey, R.A., 1986, Paleomagnetism, potassium-argon ages, and geology of rhyolite and associated rocks of the Valles Caldera, New Mexico: Geological Society of America Memoir 116, p. 211-248.</ref><ref>Izett, G.A., Obradovich, J.D., Naeser, C.W., and Cebula, G.T., 1981, Potassium-argon and fission-track ages of Cerro Toledo rhyolite tephra in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico, in Shorter contributions to isotope research in the western United States: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1199-D, p. 37-43.</ref> [[Yellowstone Caldera]] (0.7 Ma).<ref>Christiansen, R.L., and Blank, H.R., 1972, Volcanic stratigraphy of the Quaternary rhyolite plateau in Yellowstone National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 729-B, p. 18.</ref> |

||

*[[Kiloannum]] (ka), is a unit of time equal to one thousand years. [[Megaannum]] (Ma), is a unit of time equal to one million years, one can assume that "ago" is implied. |

*[[Kiloannum]] (ka), is a unit of time equal to one thousand years. [[Megaannum]] (Ma), is a unit of time equal to one million years, one can assume that "ago" is implied. |

||

| Line 536: | Line 538: | ||

|url = http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/images/pglossary/vei.php |title = VEI glossary entry |publisher = USGS |accessdate = 2010-03-30 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|url = http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/images/pglossary/vei.php |title = VEI glossary entry |publisher = USGS |accessdate = 2010-03-30 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

||

|url = http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hazards/gas/s02aerosols.php |title = Volcanic Sulfur Aerosols Affect Climate and the Earth's Ozone Layer - Volcanic ash vs sulfur aerosols |publisher = U.S. Geological Survey |accessdate = 2010-04-21 }}</ref> When sulfur dioxide (boiling point at [[standard state]]: -10°C) reacts with water vapor, it creates sulfate ions (the precursors to sulfuric acid), which are very reflective; ash aerosol on the other hand absorbs [[Ultraviolet]].<ref>http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=38975 Earth Observatory - Sarychev Eruption</ref> Global cooling through volcanism is the sum of the influence of the Global dimming and the influence of the high [[albedo]] of the deposited ash layer.<ref name=jones2007>{{cite journal |

|url = http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hazards/gas/s02aerosols.php |title = Volcanic Sulfur Aerosols Affect Climate and the Earth's Ozone Layer - Volcanic ash vs sulfur aerosols |publisher = U.S. Geological Survey |accessdate = 2010-04-21 }}</ref> When sulfur dioxide (boiling point at [[standard state]]: -10°C) reacts with water vapor, it creates sulfate ions (the precursors to sulfuric acid), which are very reflective; ash aerosol on the other hand absorbs [[Ultraviolet]].<ref>http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=38975 Earth Observatory - Sarychev Eruption</ref> Global cooling through volcanism is the sum of the influence of the Global dimming and the influence of the high [[albedo]] of the deposited ash layer.<ref name=jones2007>{{cite journal |

||

| doi=10.1007/s00382-007-0248-7 |

|||

| author=Jones, M.T., Sparks, R.S.J., and Valdes, P.J. | title=The climatic impact of supervolcanis ash blankets | journal=[[Climate Dynamics]] | year=2007 | volume=29 | pages= 553–564 |

| author=Jones, M.T., Sparks, R.S.J., and Valdes, P.J. | title=The climatic impact of supervolcanis ash blankets | journal=[[Climate Dynamics]] | year=2007 | volume=29 | pages= 553–564 |

||

}}</ref> The lower [[snow line]] and its higher albedo might prolong this cooling period.<ref>Jones, G.S., Gregory, J.M., Scott, P.A., Tett, S.F.B., Thorpe, R.B., 2005. An AOGCM model of the climate response to a volcanic super-eruption. Climate Dynamics 25, 725-738</ref> Bipolar comparison showed six sulfate events: [[Mount Tambora|Tambora]] (1815), [[Cosigüina]] (1835), [[Krakatoa]] (1883), [[Agung]] (1963), and [[El Chichón]] (1982), and the 1809–10 ice core event.<ref name="Dai1991">{{cite journal|last=Dai |first=Jihong |coauthors=Ellen Mosley-Thompson and Lonnie G. Thompson |year=1991 |title=Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres) |volume=96 |url=http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1991/91JD01634.shtml |pages=17,361–17,366}}</ref> And the atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation data from the [[Mauna Loa Observatory]] (MLO), [[Hawaii]] (19°32'N) detected only five eruptions:<ref>http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/mloapt.html Atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation (Preliminary) at Mauna Loa, Hawaii</ref> |

}}</ref> The lower [[snow line]] and its higher albedo might prolong this cooling period.<ref>Jones, G.S., Gregory, J.M., Scott, P.A., Tett, S.F.B., Thorpe, R.B., 2005. An AOGCM model of the climate response to a volcanic super-eruption. Climate Dynamics 25, 725-738</ref> Bipolar comparison showed six sulfate events: [[Mount Tambora|Tambora]] (1815), [[Cosigüina]] (1835), [[Krakatoa]] (1883), [[Agung]] (1963), and [[El Chichón]] (1982), and the 1809–10 ice core event.<ref name="Dai1991">{{cite journal|last=Dai |first=Jihong |coauthors=Ellen Mosley-Thompson and Lonnie G. Thompson |year=1991 |title=Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres) |volume=96|issue=D9 |url=http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1991/91JD01634.shtml |pages=17,361–17,366}}</ref> And the atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation data from the [[Mauna Loa Observatory]] (MLO), [[Hawaii]] (19°32'N) detected only five eruptions:<ref>http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/mloapt.html Atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation (Preliminary) at Mauna Loa, Hawaii</ref> |

||

*Jun 11, 2009, [[Sarychev Peak]] (?), [[Kuril Islands]], 400 tons of tephra, VEI 4 |

*Jun 11, 2009, [[Sarychev Peak]] (?), [[Kuril Islands]], 400 tons of tephra, VEI 4 |

||

**{{coord|48|05|30|N|153|12|0|E|type:mountain|name=Sarychev Peak}} |

**{{coord|48|05|30|N|153|12|0|E|type:mountain|name=Sarychev Peak}} |

||

| Line 643: | Line 646: | ||

*Siebert L., and Simkin T. (2002-). Volcanoes of the World: an Illustrated Catalog of Holocene Volcanoes and their Eruptions. [[Smithsonian Institution]], [[Global Volcanism Program]], Digital Information Series, GVP-3, (http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/). |

*Siebert L., and Simkin T. (2002-). Volcanoes of the World: an Illustrated Catalog of Holocene Volcanoes and their Eruptions. [[Smithsonian Institution]], [[Global Volcanism Program]], Digital Information Series, GVP-3, (http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/). |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| title = Volcanoes of the World |

| title = Volcanoes of the World |

||

| year = 1994 |

| year = 1994 |

||

| publisher = Geoscience Press, Tucson, 2nd edition |

| publisher = Geoscience Press, Tucson, 2nd edition |

||

| pages= 349 |

| pages= 349 |

||

| isbn = 0 945005 12 1 |

| isbn = 0 945005 12 1 |

||

| author= Simkin T., and Siebert L. }} |

|||

*{{Citation |

|||

*{{Cite document |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| contribution = Earth's volcanoes and eruptions: an overview |

| contribution = Earth's volcanoes and eruptions: an overview |

||

| editors = Sigurdsson H. |

| editors = Sigurdsson H. |

||

| Line 659: | Line 662: | ||

| place = San Diego |

| place = San Diego |

||

| year = 2000 |

| year = 2000 |

||

| contribution-url = |

| contribution-url = |

||

| postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} }} |

|||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| last= Simkin |

| last= Simkin |

||

Revision as of 18:47, 6 December 2010

This article is a list of volcanic eruptions of approximately at least magnitude 6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) or equivalent sulfur dioxide emission around the Quaternary period. Some cooled the global climate; the extent of this effect depends on the amount of sulfur dioxide emitted.[1][2] The topic in the background is an overview of the VEI and sulfur dioxide emission/ Volcanic winter relationship. Before the Holocene epoch the criteria is less strict because of scarce data available, partly for the later eruptions have destroyed the evidence. So, the known large eruptions after the Paleogene period are listed, and specially the Yellowstone hotspot, Santorini, and Taupo Volcanic Zone ones. Just some eruptions before the Neogene period are listed as well. Active volcanoes such as Stromboli, Mount Etna and Kilauea do not appear on this list, but some back-arc basin volcanoes that generated calderas do appear. Some dangerous volcanoes in "populated areas" appear many times: so Santorini, six times and Yellowstone hotspot, twenty one times. The Bismarck volcanic arc, New Britain and the Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand appear often too.

In order to keep the list manageable, the eruptions in the Holocene on the link: Holocene Volcanoes in Kamchatka were not added yet, but they are listed on the Peter L. Ward's supplemental table.[3]

Large Quaternary eruptions

The Holocene epoch begins 11,700 years BP[4], (10 000 14C years ago)

Since 1000 AD

- Pinatubo, island of Luzon, Philippines; 1991, Jun 15; VEI 6; 6 to 16 cubic kilometers (1.4 to 3.8 cu mi) of tephra;[5] an estimated 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted[1]

- Novarupta, Alaska Peninsula; 1912, Jun 6; VEI 6; 13 to 15 cubic kilometers (3.1 to 3.6 cu mi) of lava[6][7][8]

- Santa Maria, Guatemala; 1902, Oct 24; VEI 6; 20 cubic kilometres (4.8 cu mi) of tephra[9]

- Krakatoa, Indonesia; 1883, August 26–27; VEI 6; 21 cubic kilometres (5.0 cu mi) of tephra[10]

- Mount Tambora, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia; 1815, Apr 10; VEI 7; 150 cubic kilometres (36 cu mi) of tephra[5]; an estimated 200 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted, produced the "Year Without a Summer"[11]

- Grímsvötn, Northeastern Iceland; 1783–1785; Laki; 1783–1784; VEI 6; 14 cubic kilometers of lava, an estimated 120 million tons of sulfur dioxide were emitted, produced a Volcanic winter, 1783, on the North Hemisphere.[12]

- Long Island (Papua New Guinea), Northeast of New Guinea; 1660 ±20; VEI 6; 30 cubic kilometers (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[5]

- Kolumbo, Santorini, Greece; 1650, Sep 27; VEI 6; 60 cubic kilometers (14.4 cu mi) of tephra[13]

- Huaynaputina, Peru; 1600, Feb 19; VEI 6; 30 cubic kilometres (7.2 cu mi) of tephra[14]

- Billy Mitchell, Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea; 1580 ±20; VEI 6; 14 cubic kilometres (3.4 cu mi) of tephra[5]

- Bárðarbunga, Northeastern Iceland; 1477; VEI 6; 10 cubic kilometres (2.4 cu mi) of tephra[5]

- 1452-53 ice core event, New Hebrides arc, Vanuatu; location of this eruption in the South Pacific is uncertain; only pyroclastic flows are found at Kuwae; 36 to 96 cubic kilometers (8.6 to 23.0 cu mi) of tephra; 175-700 million tons of sulfuric acid[15][16][17]

- Quilotoa, Ecuador; 1280(?); VEI 6; 21 cubic kilometres (5.0 cu mi) of tephra[5]

- 1258 ice core event, tropics; 200 to 800 cubic kilometers (48.0 to 191.9 cu mi) of tephra[18]

Some eruptions since the Pleistocene

2.588 ± 0.005 million years BP, Quaternary period and Pleistocene epoch begins.

- Eifel hotspot, Laacher See, Vulkan Eifel, Germany; 12.9 ka; VEI 6; 6 cubic kilometers (1.4 cu mi) of tephra.[19][20][21][22]

- Emmons Lake Caldera (size: 11 x 18 km), Aleutian Range, 17 ka ±5; more than 50 km3 (12 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Lake Barrine, Atherton Tableland, North Queensland, Australia; was formed over 17 ka.

- Menengai, East African Rift, Kenya; 29 ka[5]

- Morne Diablotins, Commonwealth of Dominica; VEI 6; 30 ka (Grand Savanne Ignimbrite).[23]

- Kurile Lake, Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia; Golygin eruption; about 41.5 ka; VEI 7[5]

- Maninjau Caldera (size: 20 x 8 km), West Sumatra; VEI 7; around 52 ka; 220 to 250 cubic kilometers (52.8 to 60.0 cu mi) of tephra.[24]

- Atitlán Caldera (size: 17 x 20 km), Guatemalan Highlands; Los Chocoyos eruption; formed in an eruption 84 ka; VEI 7; 300 km3 (72 cu mi) of tephra.[25]

- Mount Aso (size: 24 km wide), island of Kyūshū, Japan; 90 ka; last eruption was more than 600 cubic kilometers (144 cu mi) of tephra.[3][26]

- Sierra La Primavera volcanic complex (size: 11 km wide), Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico; 95 ka; 20 cubic kilometers (5 cu mi) of Tala Tuff.[3][27]

- Mount Aso (size: 24 km wide), island of Kyūshū, Japan; 120 ka; 80 km3 (19 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Mount Aso (size: 24 km wide), island of Kyūshū, Japan; 140 ka; 80 km3 (19 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Puy de Sancy, Massif Central, central France; it is part of an ancient stratovolcano which has been inactive for about 220,000 years.

- Emmons Lake Caldera (size: 11 x 18 km), Aleutian Range, 233 ka; more than 50 km3 (12 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Mount Aso (size: 24 km wide), island of Kyūshū, Japan; caldera formed as a result of four huge caldera eruptions; 270 ka; 80 cubic kilometers (19 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Uzon-Geyzernaya calderas (size: 9 x 18 km), Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia; 325-175 ka[28] 20 km3 (4.8 cu mi) of ignimbrite deposits.[29]

- Diamante Caldera–Maipo volcano complex (size: 20 x 16 km), Argentina-Chile; 450 ka; 450 cubic kilometers (108 cu mi) of tephra.[3][30]

- Three Sisters (Oregon), USA; Tumalo volcanic center; with eruptions from 600 - 700 to 170 ka years ago

- Uinkaret volcanic field, Arizona, USA; the Colorado River was dammed by lava flows multiple times from 725 to 100 ka.[31]

- Sutter Buttes, Central Valley of California, USA; were formed over 1.5 Ma by a now-extinct volcano.

- Ebisutoge-Fukuda tephras, Japan; 1.75 Ma; 380 to 490 cubic kilometers (91.2 to 117.6 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Cerro Galán (size: 32 km wide), Catamarca Province, northwestern Argentina; 2.2 Ma; VEI 8; 1,050 cubic kilometers (252 cu mi) of Cerro Galán Ignimbrite.[32]

Some eruptions since the Pliocene epoch

*Approximately 2.588 million years BP, Quaternary period and Pleistocene epoch begins. Most eruptions before the Quaternary period have an unknown VEI.

- Boring Lava Field, Boring, Oregon, USA; the zone became active at least 2.7 Ma, and has been extinct for about 300,000 years.[33]

- Norfolk Island, Australia; remnant of a basaltic volcano active around 2.3 to 3 Ma.[34]

- Pastos Grandes Caldera (size: 40 x 50 km), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, Bolivia; 2.9 Ma; VEI 7; more than 820 cubic kilometers (197 cu mi) of Pastos Grandes Ignimbrite.[35]

- Little Barrier Island, northeastern coast of New Zealand's North Island; it erupted from 1 million to 3 Ma.[36]

- Mount Kenya; a stratovolcano created approximately 3 Ma after the opening of the East African rift.[37]

- Pacana Caldera (size: 60 x 35 km), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, northern Chile; 4 Ma; VEI 8; 2,500 cubic kilometers (600 cu mi) of Atana Ignimbrite.[38]

- Frailes Plateau, Bolivia; 4 Ma; 620 cubic kilometers (149 cu mi) of Frailes Ignimbrite E.[3][39]

- Cerro Galán (size: 32 km wide), Catamarca Province, northwestern Argentina; 4.2 Ma; 510 cubic kilometers (122 cu mi) of Real Grande and Cueva Negra tephra.[3]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Heise volcanic field, Idaho; Kilgore Caldera (size: 80 x 60 km); VEI 8; 1,800 cubic kilometers (432 cu mi) of Kilgore Tuff; 4.45 Ma ±0.05.[3][40]

- Kari Kari Caldera, Frailes Plateau, Bolivia; 5 Ma; 470 cubic kilometers (113 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

Some eruptions before the Pliocene epoch

- Approximately 5.332 million years BP, Pliocene epoch begins

- Lord Howe Island, Australia; Mount Lidgbird and Mount Gower are both made of basalt rock, remnants of lava flows that once filled a large volcanic caldera 6.4 Ma.[41]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Heise volcanic field, Idaho; 5.51 Ma ±0.13 (Conant Creek Tuff).[40]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Heise volcanic field, Idaho; 5.6 Ma; 500 cubic kilometers (120 cu mi) of Blue Creek Tuff.[3]

- Cerro Panizos (size: 18 km wide), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, Bolivia; 6.1 Ma; 652 cubic kilometers (156 cu mi) of Panizos Ignimbrite.[3][42]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Heise volcanic field, Idaho; 6.27 Ma ±0.04 (Walcott Tuff).[40]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Heise volcanic field, Idaho; Blacktail Caldera (size: 100 x 60 km), Idaho; 6.62 Ma ±0.03; 1,500 cubic kilometers (360 cu mi) of Blacktail Tuff.[3][40]

- Pastos Grandes Caldera (size: 40 x 50 km), Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex, Bolivia; 8.3 Ma; 652 cubic kilometers (156 cu mi) of Sifon Ignimbrite.[3]

- Manus Island, Admiralty Islands, northern Papua New Guinea; 8–10 Ma

- Banks Peninsula, New Zealand; Akaroa erupted 9 Ma, Lyttelton erupted 12 Ma.[43]

- Mascarene Islands were formed in a series of undersea volcanic eruptions 8-10 Ma, as the African plate drifted over the Réunion hotspot.

- Yellowstone hotspot, Twin Fall volcanic field, Idaho; 8.6 to 10 Ma.[44]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Picabo volcanic field, Idaho; 10.21 Ma ± 0.03 (Arbon Valley Tuff).[40]

- Mount Cargill, New Zealand; the last eruptive phase ended some 10 Ma. The center of the caldera is about Port Chalmers, the main port of the city of Dunedin.[45][46][47]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Idaho; Bruneau-Jarbidge volcanic field; 10.0 to 12.5 Ma (Ashfall Fossil Beds eruption).[44]

- Anahim hotspot, British Columbia, Canada; has generated the Anahim Volcanic Belt over the last 13 million years.

- Yellowstone hotspot, Owyhee-Humboldt volcanic field, Nevada/ Oregon; around 12.8 to 13.9 Ma.[44][48]

- Campi Flegrei, Naples, Italy; 14.9 Ma; 79 cubic kilometers (19 cu mi) of Neapolitan Yellow Tuff.[3]

- Huaylillas Ignimbrite, Bolivia, southern Peru, northern Chile; 15 Ma ±1; 1,100 cubic kilometers (264 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (North), Trout Creek Mountains, Whitehorse Caldera (size: 15 km wide), Oregon; 15 Ma; 40 cubic kilometers (10 cu mi) of Whitehorse Creek Tuff.[3][49]

- Yellowstone hotspot (?), Lake Owyhee volcanic field; 15.0 to 15.5 Ma.[50]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Jordan Meadow Caldera, (size: 10–15 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 15.6 Ma; 350 cubic kilometers (84 cu mi) Longridge Tuff member 2-3.[3][44][49][51]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Longridge Caldera, (size: 33 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 15.6 Ma; 400 cubic kilometers (96 cu mi) Longridge Tuff member 5.[3][44][49][51]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Calavera Caldera, (size: 17 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 15.7 Ma; 300 cubic kilometers (72 cu mi) of Double H Tuff.[3][44][49][51]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Hoppin Peaks Caldera, 16 Ma; Hoppin Peaks Tuff.[52]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (North), Trout Creek Mountains, Pueblo Caldera (size: 20 x 10 km), Oregon; 15.8 Ma; 40 cubic kilometers (10 cu mi) of Trout Creek Mountains Tuff.[3][49][52]

- Yellowstone hotspot, McDermitt volcanic field (South), Washburn Caldera, (size: 30 x 25 km wide), Nevada/ Oregon; 16.548 Ma; 250 cubic kilometers (60 cu mi) of Oregon Canyon Tuff.[3][49][51]

- Yellowstone hotspot (?), Northwest Nevada volcanic field (NWNV), Virgin Valley, High Rock, Hog Ranch, and unnamed calderas; West of Pine Forest Range, Nevada; 15.5 to 16.5 Ma.[53]

- Yellowstone hotspot, Steens and Columbia River flood basalts, Pueblo, Steens, and Malheur Gorge-region, Pueblo Mountains, Steens Mountain, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, USA; most vigorous eruptions were from 14–17 Ma; 180,000 cubic kilometers (43,184 cu mi) of lava.[3][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]

- Mount Lindesay (New South Wales), Australia; is part of the remnants of the Nandewar extinct volcano that ceased activity about 17 Ma after 4 million years of activity.

- Oxaya Ignimbrites, northern Chile (around 18°S); 19 Ma; 3,000 cubic kilometers (720 cu mi) of tephra.[3]

- Pemberton Volcanic Belt was erupting about 21 to 22 Ma.[61]

Overview

This is a sortable summary of the list above (Common Era), date uncertainties, tephra volume uncertainties and references are not repeated.

| Caldera/ Caldera complex name | Volcanic arc/ belt or Subregion or Hotspot |

VEI | Date | Tephra or eruption name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mount Pinatubo | Luzon Volcanic Arc | 6 | 1991, Jun 15 | |

| Novarupta | Aleutian Range | 6 | 1912, Jun 6 | |

| Santa María | Central America Volcanic Arc | 6 | 1902, Oct 24 | |

| Mount Tarawera | Taupo Volcanic Zone | 5 | 1886, Jun 10 | |

| Krakatoa | Sunda Arc | 6 | 1883, Aug 26-27 | |

| Mount Tambora | Lesser Sunda Islands | 7 | 1815, Apr 10 | |

| Grimsvotn and Laki | Iceland | 6 | 1783-85 | |

| Long Island (Papua New Guinea) | Bismarck Volcanic Arc | 6 | 1660 | |

| Kolumbo, Santorini | South Aegean Volcanic Arc | 6 | 1650, Sep 27 | |

| Huaynaputina | Andes, Central Volcanic Zone | 6 | 1600, Feb 19 | |

| Billy Mitchell | Bougainville & Solomon Is. | 6 | 1580 | |

| Bardarbunga | Iceland | 6 | 1477 | |

| 1452-53 ice core event | New Hebrides Arc | 6 | 1452-53 | |

| Quilotoa | Andes, Northern Volcanic Zone | 6 | 1280 | |

| Baekdu Mountain | China/ North Korea border | 7 | 969 AD | Tianchi eruption |

| Katla | Iceland | 6 | 934-940 AD | Eldgjá eruption |

| Ceboruco | Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt | 6 | 930 AD | |

| Dakataua | Bismarck Volcanic Arc | 6 | 800 AD | |

| Pago | Bismarck Volcanic Arc | 6 | 710 AD | |

| Mount Churchill | eastern Alaska, USA | 6 | 700 AD | |

| Rabaul Caldera | Bismarck Volcanic Arc | 6 | 540 AD | |

| Ilopango | Central America Volcanic Arc | 6 | 450 AD | |

| Ksudach | Kamchatka Peninsula | 6 | 240 AD | |

| Taupo Caldera | Taupo Volcano | 7 | 230 AD | Hatepe eruption |

| Mount Vesuvius | Italy | 5 | 79 AD | Pompeii eruption |

| Mount Churchill | eastern Alaska, USA | 6 | 60 AD | |

| Ambrym | New Hebrides Arc | 6 | 50 AD |

Note: Caldera names tend to change over time. For example, Okataina Caldera, Haroharo Caldera, Haroharo volcanic complex, Tarawera volcanic complex had the same magma source in the Taupo Volcanic Zone. Yellowstone Caldera, Henry's Fork Caldera, Island Park Caldera, Heise Volcanic Field had all Yellowstone hotspot as magma source.

Very old volcanism

- Approximately 23,030,000 years BP, the Neogene period and the Miocene epoch begins.

- La Garita Caldera (size: 100 x 35 km), Wheeler Geologic Area, Central Colorado volcanic field, Colorado, USA; VEI 8; 5,000 cubic kilometers (1,200 cu mi) of Fish Canyon Tuff was blasted out in a major single eruption about 27.8 Ma.[32][62][63]

- Unknown source, Ethiopia; 29 Ma ±1; 3,000 cubic kilometers (720 cu mi) of Green Tuff and SAM.[3]

- Sam Ignimbrite, Yemen; 29.5 Ma; at least 5,550 cubic kilometers (1,332 cu mi) of distal tuffs associated with the ignimbrites.[64]

- Jabal Kura’a Ignimbrite, Yemen; 29.6 Ma; at least 3,700 cubic kilometers (888 cu mi) of distal tuffs associated with the ignimbrites.[64]

- About 33.9 million BP, Oligocene epoch of the Paleogene period begins

- Bennett Lake Volcanic Complex, British Columbia/ Yukon, Canada; around 50 Ma; VEI 7; 850 cubic kilometers (204 cu mi) of tephra.[65]

- Canary hotspot is believed to have first appeared about 60 million years ago.

- Approximately 65.5 million years BP, K–T boundary/ extinction event

- Réunion hotspot, Deccan Traps, India, formed between 60 and 68 Ma

- The Louisville hotspot has produced the Louisville seamount chain, it is active for at least 80 million years. It may have originated the Ontong Java Plateau around 120 Ma.

- Hawaii hotspot, Meiji Seamount is the oldest seamount in the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, with an estimated age of 82 million years.

- Paraná and Etendeka traps, Brazil, Namibia and Angola; 128 to 138 Ma.[66]

- Glen Coe, Scotland; VEI 8; 420 Ma

- Scafells, Lake District, England; VEI 8; Ordovician (488.3 - 443.7 Ma).

- Approximately 2,500 million years BP, Proterozoic eon of the Precambrian eon begins

- Mackenzie Large Igneous Province, Canadian Shield, Canada; 1,270 Ma.

- About 3,800 million years BP, Archean eon of the Precambrian eon begins

- Blake River Megacaldera Complex, Misema Caldera, Ontario-Quebec border, Canada; 2,704-2,707 Ma.[65]

Notes

- The Mackenzie Large Igneous Province contains the largest and best-preserved continental flood basalt terrain on Earth.[67] The Mackenzie dike swarm throughout the Mackenzie Large Igneous Province is also the largest dike swarm on Earth, covering an area of 2,700,000 km2 (1,000,000 sq mi).[68]

- The Bachelor (27.4 Ma), San Luis (27-26.8 Ma), and Creede (26 Ma) calderas partially overlap each other and are nested within the large La Garita (27.6 Ma) caldera, forming the central caldera cluster of the San Juan volcanic field, Wheeler Geologic Area, La Garita Wilderness. Creede, Colorado and San Luis Peak (Continental Divide of the Americas) are nearby. North Pass Caldera is northeastern the San Juan Mountains, North Pass. The Platoro volcanic complex lies southeastern of the central caldera cluster. The center of the western San Juan caldera cluster lies just West of Lake City, Colorado.

- The Rio Grande rift includes the San Juan volcanic field, the Valles Caldera, the Potrillo volcanic field, and the Socorro-Magdalena magmatic system.[69] The Socorro Magma Body is uplifting the surface at approximately 2 mm/year.[70][71]

- The southwestern Nevada volcanic field, or Yucca Mountain volcanic field, includes: Stonewall Mountain caldera complex, Black Mountain Caldera, Silent Canyon Caldera, Timber Mountain - Oasis Valley caldera complex, Crater Flat Group, and Yucca Mountain. Towns nearby: Beatty, Mercury, Goldfield.[72] It is aligned as a Crater Flat volcanic field, Réveille Range, Lunar Crater volcanic field, Zone (CFLC).[73] The Marysvale Volcanic Field, southwestern Utah is nearby too.

- McDermitt volcanic field, or Orevada rift volcanic field, Nevada/ Oregon, nearby are: McDermitt, Trout Creek Mountains, Bilk Creek Mountains, Steens Mountain, Jordan Meadow Mountain (6,816 ft), Long Ridge, Trout Creek, and Whitehorse Creek.

- Emmons Lake stratovolcano (caldera size: 11 x 18 km), Aleutian Range, was formed through six eruptions. Mount Emmons, Mount Hague, and Double Crater are post-caldera cones.[5]

- The topography of the Basin and Range Province is a result of crustal extension within this part of the North American Plate (rifting of the North American craton or Laurentia from Western North America; e.g. Gulf of California, Rio Grande rift, Oregon-Idaho graben). The crust here has been stretched up to 100% of its original width.[74] In fact, the crust underneath the Basin and Range, especially under the Great Basin (includes Nevada), is some of the thinnest in the world.

- Topographically visible calderas: South part of the McDermitt volcanic field (four overlapping and nested calderas), West of McDermitt; Cochetopa Park Caldera, West of the North Pass; Henry's Fork Caldera; Banks Peninsula, New Zealand (Photo) and Valles Caldera. Newer drawings show McDermitt volcanic field (South), as five overlapping and nested calderas. Hoppin Peaks Caldera is included too.

- Repose periods: Toba (0.38 Ma),[75] Valles Caldera (0.35 Ma),[76][77] Yellowstone Caldera (0.7 Ma).[78]

- Kiloannum (ka), is a unit of time equal to one thousand years. Megaannum (Ma), is a unit of time equal to one million years, one can assume that "ago" is implied.

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI)

| VEI | Tephra Volume (cubic kilometers) |

Example |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Effusive | Masaya Volcano, Nicaragua, 1570 |

| 1 | >0.00001 | Poás Volcano, Costa Rica, 1991 |

| 2 | >0.001 | Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand, 1971 |

| 3 | >0.01 | Nevado del Ruiz, Colombia, 1985 |

| 4 | >0.1 | Eyjafjallajökull, Iceland, 2010 |

| 5 | >1 | Mount St. Helens, United States, 1980 |

| 6 | >10 | Krakatoa, Indonesia, 1883 |

| 7 | >100 | Mount Tambora, Indonesia, 1815 |

| 8 | >1000 | Yellowstone Caldera, United States, Pleistocene |

Volcanic dimming

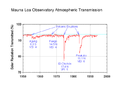

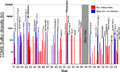

The Global dimming through volcanism (ash aerosol and sulfur dioxide) is quite independent of the eruption VEI.[79][80][81] When sulfur dioxide (boiling point at standard state: -10°C) reacts with water vapor, it creates sulfate ions (the precursors to sulfuric acid), which are very reflective; ash aerosol on the other hand absorbs Ultraviolet.[82] Global cooling through volcanism is the sum of the influence of the Global dimming and the influence of the high albedo of the deposited ash layer.[83] The lower snow line and its higher albedo might prolong this cooling period.[84] Bipolar comparison showed six sulfate events: Tambora (1815), Cosigüina (1835), Krakatoa (1883), Agung (1963), and El Chichón (1982), and the 1809–10 ice core event.[85] And the atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation data from the Mauna Loa Observatory (MLO), Hawaii (19°32'N) detected only five eruptions:[86]

- Jun 11, 2009, Sarychev Peak (?), Kuril Islands, 400 tons of tephra, VEI 4

- Jun 12-15, 1991 (eruptive climax), Mount Pinatubo, Philippines, 11,000 ±0.5 tons of tephra, VEI 6

- Global cooling: 0.5°C,[87] 15°08′0″N 120°21′0″E / 15.13333°N 120.35000°E

- Mar 28, 1982, El Chichón, Mexico, 2,300 tons of tephra, VEI 5

- Oct 10, 1974, Volcán de Fuego, Guatemala, 400 tons of tephra, VEI 4

- Feb 18, 1963, Agung, Lesser Sunda Islands, 100 tons of lava, more than 1,000 tons of tephra, VEI 5

- Northern Hemisphere cooling: 0.3°C,[88]8°20′30″S 115°30′30″E / 8.34167°S 115.50833°E

But very large sulfur dioxide emissions overdrive the oxidizing capacity of the atmosphere. Carbon monoxide's and methane's concentration goes up (greenhouse gases), global temperature goes up, ocean's temperature goes up, and ocean's carbon dioxide solubility goes down.[2]

-

Location of Mount Pinatubo, showing area over which ash from the 1991 eruption fell.

-

Satellite measurements of ash and aerosol emissions from Mount Pinatubo.

-

MLO transmission ratio - Solar radiation reduction due to volcanic eruptions

-

NASA, Global Dimming - El Chichon, VEI 5; Pinatubo, VEI 6.

-

Sulfur dioxide emissions by volcanoes. Mount Pinatubo: 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide.

-

TOMS sulfur dioxide from the June 15, 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo.

-

Sarychev Peak: the sulphur dioxide cloud generated by the eruption on June 12, 2009 (in Dobson units).

Some maps

-

Yellowstone sits on top of three overlapping calderas. (USGS)

-

Diagram of Island Park and Henry's Fork Caldera.

-

Steens Mountain, McDermitt volcanic field and Oregon/ Nevada stateline.

-

Location of Yellowstone Hotspot in Millions of Years Ago.

-

Snake River Plain, image from NASA's Aqua satellite, 2008

-

Jemez Ranger District and Jemez Mountains, Santa Fe National Forest.

See also

- Volcanic winter

- Year Without a Summer

- Extreme weather events of 535–536

- Dense-rock equivalent

- Volcanic Explosivity Index

- Supervolcano

- Volcanic arc

- Stratospheric sulfur aerosols

- Geologic timeline of Western North America

| class="col-break " |

- Lists of volcanoes

- List of volcanoes in Papua New Guinea

- List of volcanoes in Mexico

- List of volcanoes in Iceland

- Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt

- Decade Volcanoes

- Hotspot (geology)

- Pacific Ring of Fire

Further reading

- Ammann, Caspar M. (6 March 2003). "Statistical analysis of tropical explosive volcanism occurrences over the last 6 centuries" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (5): 1210. doi:10.1029/2002GL016388. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Froggatt, P.C. (1990). "A review of late Quaternary silicic and some other tephra formations from New Zealand: their stratigraphy, nomenclature, distribution, volume, and age". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 33: 89–109. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) [dead link] - Lipman, P.W. (Sept. 30, 1984). "The Roots of Ash Flow Calderas in Western North America: Windows Into the Tops of Granitic Batholiths". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B10): 8801–8841. doi:10.1029/JB089iB10p08801.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Mason, Ben G. (2004). "The size and frequency of the largest explosive eruptions on Earth". Bulletin of Volcanology. 66 (8): 735–748. doi:10.1007/s00445-004-0355-9.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Newhall, Christopher G., Dzurisin, Daniel (1988); Historical unrest at large calderas of the world, USGS Bulletin 1855, p. 1108 [2]

- Siebert L., and Simkin T. (2002-). Volcanoes of the World: an Illustrated Catalog of Holocene Volcanoes and their Eruptions. Smithsonian Institution, Global Volcanism Program, Digital Information Series, GVP-3, (http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/).

- Simkin T., and Siebert L. (1994). Volcanoes of the World. Geoscience Press, Tucson, 2nd edition. p. 349. ISBN 0 945005 12 1.

- Simkin T., and Siebert L. (2000). "Encyclopedia of Volcanoes" (Document). San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 249–261Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|contribution-url=and|volume=(help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Simkin, T. (1981). Volcanoes of the World: A Regional Directory, Gazeteer, and Chronology of Volcanism During the Last 10,000 Years. Hutchinson-Ross, Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. p. 232. ISBN 0 87933 408 8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Stern, Charles R. (December 2004). "Active Andean volcanism: its geologic and tectonic setting". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (2): 161–206. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000200001. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - United States Geological Survey; Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, Washington; Index to CVO online volcanoes

- Map: Tom Simkin, Robert I. Tilling, Peter R. Vogt, Stephen H. Kirby, Paul Kimberly, and David B. Stewart, Third Edition (Published 2006) interactive world map of Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Impact Craters, and Plate Tectonics

- Ward, Peter L. (2 April 2009). "Sulfur Dioxide Initiates Global Climate Change in Four Ways" (PDF). Thin Solid Films. 517 (11): 3188–3203. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2009.01.005. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Supplementary Table I: "Supplementary Table to P.L. Ward, Thin Solid Films (2009) Major volcanic eruptions and provinces" (PDF). Teton Tectonics. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- Supplementary Table II: "Supplementary References to P.L. Ward, Thin Solid Films (2009)" (PDF). Teton Tectonics. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

References

- ^ a b Robock, A., C.M. Ammann, L. Oman, D. Shindell, S. Levis, and G. Stenchikov (2009). "Did the Toba volcanic eruption of ~74k BP produce widespread glaciation?". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114: D10107. doi:10.1029/2008JD011652.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ward, Peter L. (2 April 2009). "Sulfur Dioxide Initiates Global Climate Change in Four Ways". Thin Solid Films. 517 (11): 3188–3203. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2009.01.005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Supplementary Table to P.L. Ward, Thin Solid Films (2009) Major volcanic eruptions and provinces" (PDF). Teton Tectonics. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ "International Stratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/largeeruptions.cfm Large Holocene Eruptions

- ^ Brantley, Steven R. (1999-01-04). Volcanoes of the United States. Online Version 1.1. United States Geological Survey. p. 30. ISBN 0160450543. OCLC 156941033 30835169 44858915. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Judy Fierstein (1998). "Can Another Great Volcanic Eruption Happen in Alaska? - U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 075-98". Version 1.0. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fierstein, Judy (2004-12-11). "The plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Katmai National Park, Alaska". Bulletin of Volcanology. 54 (8). Springer: 646. doi:10.1007/BF00430778.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Santa Maria". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ Hopkinson, Deborah (Jan 2004). "The Volcano That Shook the world: Krakatoa 1883". 11 (4). New York: Storyworks: 8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|from=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.earlham.edu/~ethribe/web/tambora.htm

- ^ BBC Timewatch: "Killer Cloud", broadcast 19 January 2007

- ^ Haraldur Sigurdsson, S. Carey, C. Mandeville, 1990. "Assessment of mass, dynamics and environmental effects of the Minoan eruption of the Santorini volcano" in Thera and the Aegean World III: Proceedings of the Third Thera Conference, vol II, pp 100-12.

- ^ "Huaynaputina". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ Nemeth, Karoly (2007). "Kuwae caldera and climate confusion". The Open Geology Journal. 1 (5): 7–11. doi:10.2174/1874262900701010007.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gao, Chaochao (27 June 2006). "The 1452 or 1453 A.D. Kuwae eruption signal derived from multiple ice core records: Greatest volcanic sulfate event of the past 700 years". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111: D12107. doi:10.1029/2005JD006710. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Witter, J.B. (Januar 2007). "The Kuwae (Vanuatu) eruption of AD 1452: potential magnitude and volatile release". Bulletin of Vulcanology. 69 (3): 301–318. doi:10.1007/s00445-006-0075-4.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Oppenheimer, Clive (19 Mar 2003). "Ice core and palaeoclimatic evidence for the timing and nature of the great mid-13th century volcanic eruption". International Journal of Climatology. 23 (4). Royal Meteorological Society: 417–426. doi:10.1002/joc.891.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ van den Bogaard, P (1995). 40Ar/(39Ar) ages of sanidine phenocrysts from Laacher See Tephra (12,900 yr BP): Chronostratigraphic and petrological significance

- ^ de Klerk et al. (2008). Environmental impact of the Laacher See eruption at a large distance from the volcano: Integrated palaeoecological studies from Vorpommern (NE Germany)

- ^ Baales, Michael; Jöris, Olaf; Street, Martin; Bittmann, Felix; Weninger, Bernhard; Wiethold, Julian (2002). "Impact of the Late Glacial Eruption of the Laacher See Volcano, Central Rhineland, Germany". Quaternary Research. 58 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2379.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Forscher warnen vor Vulkan-Gefahr in der Eifel. Spiegel Online, 13. Februar 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2008

- ^ Carey, Steven N. (1980). "The Roseau Ash: Deep-sea Tephra Deposits from a Major Eruption on Dominica, Lesser Antilles Arc". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 7 (1–2): 67–86. doi:10.1016/0377-0273(80)90020-7.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Alloway, Brent V. (30 October 2004). "Correspondence between glass-FT and 14C ages of silicic pyroclastic flow deposits sourced from Maninjau caldera, west-central Sumatra". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 227 (1–2). Elsevier: 121. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.08.014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Guatemala Volcanoes and Volcanics". USGS - CVO. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ Cities on Volcanoes 5 conference: A6: Living with Aso-Kuju volcanoes and geothermal field .

- ^ "Sierra la Primavera". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Uzon, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ Sruoga, Patricia (September 2005). "Volcanological and geochemical evolution of the Diamante Caldera–Maipo volcano complex in the southern Andes of Argentina (34°10′S)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 19 (4): 399–414. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2005.06.003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Karlstrom, K. (2007). "40Ar/39Ar and field studies of Quaternary basalts in Grand Canyon and model for carving Grand Canyon: Quantifying the interaction of river incision and normal faulting across the western edge of the Colorado Plateau". GSA Bulletin. 119 (11/12): 1283–1312. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2007)119[1283:AAFSOQ]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ben G. Mason (2004). "The size and frequency of the largest explosive eruptions on Earth". Bulletin of Volcanology. 66 (8): 735–748. doi:10.1007/s00445-004-0355-9.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wood, Charles A. (1990). Volcanoes of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 170–172.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Geological origins, Norfolk Island Tourism. Accessed 2007-04-13.

- ^ Ort, M. H.; de Silva, S.; Jiminez, N.; Salisbury, M.; Jicha, B. R. and Singer, B. S. (2009). Two new supereruptions in the Altiplano-Puna Volcanic Complex of the Central Andes.

- ^

Lindsay, Jan M. (1999). "Geology, petrology, and petrogenesis of Little Barrier Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 42 (2): 155–168. doi:10.1080/00288306.1999.9514837. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ Philippe Nonnotte. "Étude volcano-tectonique de la zone de divergence Nord-Tanzanienne (terminaison sud du rift kenyan) – Caractérisation pétrologique et géochimique du volcanisme récent (8 Ma – Actuel) et du manteau source – Contraintes de mise en place thèse de doctorat de l'université de Bretagne occidentale, spécialité : géosciences marines" (PDF).

- ^ Lindsay, J. M.;de Silva, S.;Trumbull, R.; Emmermann, R. and Wemmer, K. (2001). La Pacana caldera, N. Chile: a re-evaluation of the stratigraphy and volcanology of one of the world's largest resurgent calderas, Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 106 (1-2), 145–173. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(00)00270-5.

- ^ Frailes Plateau

- ^ a b c d e Morgan, Lisa A. Morgan (March 2005). "Timing and development of the Heise volcanic field, Snake River Plain, Idaho, western USA" (PDF). GSA Bulletin. 117 (3–4): 288–306. doi:10.1130/B25519.1. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Geography and Geology, Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Retrieved on 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Cerro Panizos". Volcano World. Retrieved 2010-03-15. [dead link]

- ^ Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- ^ a b c d e f "Mark Anders: Yellowstone hotspot track". Columbia University, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO). Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ Coombs, D. S., Dunedin Volcano, Misc. Publ. 37B, pp. 2–28, Geol. Soc. of N. Z., Dunedin, 1987.

- ^ Coombs, D. S., R. A. Cas, Y. Kawachi, C. A. Landis, W. F. Mc-Donough, and A. Reay, Cenozoic volcanism in north, east and central Otago, Bull. R. Soc. N. Z., 23, 278–312, 1986.

- ^ Bishop, D.G., and Turnbull, I.M. (compilers) (1996). Geology of the Dunedin Area. Lower Hutt, NZ: Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences. ISBN 0-478-09521-X.

- ^ Sawyer, David A. (October 1994). "Episodic caldera volcanism in the Miocene southwestern Nevada volcanic field: Revised stratigraphic framework, 40Ar/39Ar geochronology, and implications for magmatism and extension". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 106 (10): 1304–1318. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1994)106<1304:ECVITM>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Lipman, P.W. (Sept. 30, 1984). "The Roots of Ash Flow Calderas in Western North America: Windows Into the Tops of Granitic Batholiths". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B10): 8801–8841. doi:10.1029/JB089iB10p08801.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rytuba, James J. (May 3–5, 2004). "Volcanism Associated with Eruption of the Steens Basalt and Inception of the Yellowstone Hotspot". Rocky Mountain (56th Annual) and Cordilleran (100th Annual) Joint Meeting. Paper No. 44-2. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Steve Ludington, Dennis P. Cox, Kenneth W. Leonard, and Barry C. Moring (1996). "An Analysis of Nevada's Metal-Bearing Mineral Resources" (Document). Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of NevadaTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|volume=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution-url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Rytuba, J.J. (1984). "Peralkaline ash flow tuffs and calderas of the McDermitt Volcanic Field, southwest Oregon and north central Nevada". Journal of Geophysical Research. 89 (B10): 8616–8628. doi:10.1029/JB089iB10p08616. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthew A. Coble, and Gail A. Mahood (2008). New geologic evidence for additional 16.5-15.5 Ma silicic calderas in northwest Nevada related to initial impingement of the Yellowstone hot spot (PDF). Collapse Calderas Workshop, IOP Conf. Series. doi:10.1088/1755-1307/3/1/012002. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Carson, Robert J. and Pogue, Kevin R. (1996). Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods:Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington. Washington State Department of Natural Resources (Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information Circular 90). ISBN none.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reidel, Stephen P. (2005). A Lava Flow without a Source: The Cohasset Flow and Its Compositional Members. The Journal of Geology, Volume 113, Pp 1 - 21. ISBN none.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brueseke, M.E. (15 March 2007). "Distribution and geochronology of Oregon Plateau (U.S.A.) flood basalt volcanism: The Steens Basalt revisited". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 161 (3): 187–214. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.12.004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ SummitPost.org, Southeast Oregon Basin and Range

- ^ USGS, Andesitic and basaltic rocks on Steens Mountain

- ^ a b GeoScienceWorld, Genesis of flood basalts and Basin and Range volcanic rocks from Steens Mountain to the Malheur River Gorge, Oregon

- ^ "Oregon: A Geologic History. 8. Columbia River Basalt: the Yellowstone hot spot arrives in a flood of fire". Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Cenozoic to Recent plate configurations in the Pacific Basin: Ridge subduction and slab window magmatism in western North America

- ^ Largest explosive eruptions: New results for the 27.8 Ma Fish Canyon Tuff and the La Garita caldera, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado

- ^ Olivier Bachmann (2002). "The Fish Canyon Magma Body, San Juan Volcanic Field, Colorado: Rejuvenation and Eruption of an Upper-Crustal Batholith". Journal of Petrology. 43 (8): 1469–1503. doi:10.1093/petrology/43.8.1469. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ingrid Ukstins Peate (2005). "Volcanic stratigraphy of large-volume silicic pyroclastic eruptions during Oligocene Afro-Arabian flood volcanism in Yemen". Bulletin of Volcanology. 68: 135–156. doi:10.1007/s00445-005-0428-4.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - ^ a b Crustal recycling during subduction at the Eocene Cordilleran margin of North America Retrieved on 2007-06-26 Cite error: The named reference "SI" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Sur l'âge des trapps basaltiques (On the ages of flood basalt events); Vincent E. Courtillot & Paul R. Renneb; Comptes Rendus Geoscience; Vol: 335 Issue: 1, January, 2003; pp: 113-140

- ^ Muskox Property - The Muskox Intrusion

- ^ The 1.27 Ga Mackenzie Large Igneous Province and Muskox layered intrusion

- ^ "Westward Migrating Ignimbrite Calderas and a Large Radiating Mafic Dike Swarm of Oligocene Age, Central Rio Grande Rift, New Mexico: Surface Expression of an Upper Mantle Diapir?" (PDF). New Mexico Tech. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ^ Fialko, Y., and M. Simons, Evidence for on-going inflation of the Socorro magma body, New Mexico, from interferometric synthetic aperture radar imaging Geop. Res. Lett., 28, 3549-3552, 2001.

- ^ "Socorro Magma Body". New Mexico Tech. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ^ "Figure: Calderas within southwestern Nevada volcanic field". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ Smith, E.I., and D.L. Keenan (30 August 2005). "Yucca Mountain Could Face Greater Volcanic Threat" (PDF). Eos, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union. 86 (35). Retrieved 1/3/09.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Geologic Provinces of the United States: Basin and Range Province on USGS.gov website Retrieved 9 November 2009

- ^ Chesner, C.A.; Westgate, J.A.; Rose, W.I.; Drake, R.; Deino, A. (1991). "Eruptive History of Earth's Largest Quaternary caldera (Toba, Indonesia) Clarified" (PDF). Geology. 19: 200–203. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1991)019<0200:EHOESL>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Doell, R.R., Dalrymple, G.B., Smith, R.L., and Bailey, R.A., 1986, Paleomagnetism, potassium-argon ages, and geology of rhyolite and associated rocks of the Valles Caldera, New Mexico: Geological Society of America Memoir 116, p. 211-248.

- ^ Izett, G.A., Obradovich, J.D., Naeser, C.W., and Cebula, G.T., 1981, Potassium-argon and fission-track ages of Cerro Toledo rhyolite tephra in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico, in Shorter contributions to isotope research in the western United States: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1199-D, p. 37-43.

- ^ Christiansen, R.L., and Blank, H.R., 1972, Volcanic stratigraphy of the Quaternary rhyolite plateau in Yellowstone National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 729-B, p. 18.

- ^ Salzer, Matthew W. (2007). "Bristlecone pine tree rings and volcanic eruptions over the last 5000 yr" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 67: 57–68. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2006.07.004. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "VEI glossary entry". USGS. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ "Volcanic Sulfur Aerosols Affect Climate and the Earth's Ozone Layer - Volcanic ash vs sulfur aerosols". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=38975 Earth Observatory - Sarychev Eruption

- ^ Jones, M.T., Sparks, R.S.J., and Valdes, P.J. (2007). "The climatic impact of supervolcanis ash blankets". Climate Dynamics. 29: 553–564. doi:10.1007/s00382-007-0248-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, G.S., Gregory, J.M., Scott, P.A., Tett, S.F.B., Thorpe, R.B., 2005. An AOGCM model of the climate response to a volcanic super-eruption. Climate Dynamics 25, 725-738

- ^ Dai, Jihong (1991). "Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres). 96 (D9): 17, 361–17, 366.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/mloapt.html Atmospheric transmission of direct solar radiation (Preliminary) at Mauna Loa, Hawaii

- ^ "Mt. Pinatubo's cloud shades global climate". Science News. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Jones, P.D., Wigley, T.M.I, and Kelly, P.M. (1982), Variations in surface air temperatures: Part I. Northern Hemisphere, 1881-1980: Monthly Weather Review, v.110, p. 59-70.

External links

- Volcano World Information

- Volcano Live, John Seach

- Volcanoes in Nicaragua

- Holocene Volcanoes in Kamchatka

- National Park Service interactive map showing trace of the hotspot over time

- Reference Database of the International Association of Volcanology (XLS file)

- Reference Database of Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (XLS file)

- Volcanic sulfate record in the GISP2 core (ftp protocol)

![Harney Basin, Steens Mountain, Owyhee and Malheur River.[59]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8f/Wpdms_shdrlfi020l_harney_basin.jpg/120px-Wpdms_shdrlfi020l_harney_basin.jpg)