Tethys (moon): Difference between revisions

→References: refs |

→References: refs |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

{{reflist|2|group=note}} |

{{reflist|2|group=note}} |

||

== |

==Citations== |

||

{{reflist|2|refs= |

{{reflist|2|refs= |

||

<ref name="Thomas2007">{{cite doi|10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012}}</ref> |

<ref name="Thomas2007">{{cite doi|10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012}}</ref> |

||

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

<ref name=Carvano2007>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.008}}</ref> |

<ref name=Carvano2007>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.008}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

==References== |

|||

*{{cite doi|10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_18}} |

|||

*{{cite doi|10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_19}} |

|||

*{{cite doi|10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_20}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 11:44, 7 May 2011

| |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. D. Cassini |

| Discovery date | March 21, 1684 |

| Designations | |

| Saturn III | |

| Adjectives | Tethyan |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 294 619 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.000 1[1][2] |

| 1.887 802 d[2] | |

| Inclination | 1.12° (to Saturn's equator) |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 1080.8 × 1062.2 × 1055 km[3] |

Mean radius | 533.00 ± 1.4 km (0.083 Earths)[3] |

| Mass | (6.174 49 ± 0.001 32)×1020 kg[4] (1.03×10−4 Earths) |

Mean density | 0.973 5 ± 0.003 8 g/cm³ [4] |

| 0.145 m/s2 | |

| 0.393 km/s | |

| synchronous | |

| zero | |

| Albedo | 1.229 ± 0.005 (geometric)[5] |

| Temperature | 86 K |

| 10.2 [6] | |

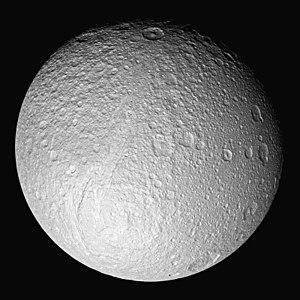

Tethys (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈtiːθ[invalid input: 'ɨ']s/ or /ˈtɛθ[invalid input: 'ɨ']s/;[note 1] Greek: Τηθύς) is a moon of Saturn that was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1684.[7]

Discovery and naming

Tethys was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1684 together with Dione, another moon of Saturn. He had also discovered two moons, Rhea and Iapetus earlier, in 1671–72.[8] Cassini observed all these moons them using a large aerial telescope he set up on the grounds of the Paris Observatory.[9]

Cassini named the four new moons as Sidera Lodoicea ("the stars of Louis") to honour king Louis XIV of France.[7] By the end of the seventeenth century, astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V (Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Iapetus).[8] Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII by bumping the older five moons up two slots. The discovery of Hyperion in 1848 changed the numbers one last time, bumping Iapetus up to Saturn VIII. Henceforth, the numbering scheme would remain fixed.

The modern names of all seven satellites of Saturn come from John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of Mimas and Enceladus.[8] In his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope,[10] he suggested the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Kronos (the Greek analogue of Saturn), be used.

Tethys is named after the titan Tethys of Greek mythology. It is also designated Saturn III or S III Tethys. The correct adjectival form of the moon's name is Tethyan, although other forms are also used.

Physical characteristics

At 1066 km in diameter, Tethys is the 16th largest moon in the Solar System, and is more massive than all known moons smaller than itself combined.[note 2] The density of Tethys is 0.97 g/cm³, indicating that it is composed almost entirely of water-ice. The mass of rocky material can not not exceed 6% of the mass of this moon.[3]

It is not known whether Tethys is differentiated into the rocky core and ice mantle. However, if it is differentiated, the radius of the core is about 145 km. Due to the action of tidal and rotational forces, Tethys has a shape of triaxial ellipsoid. The dimensions of this ellipsoid are consistent with this moon having homogeneous interior.[3] The existence of a subsurface ocean—a layer of liquid water in the interior of Tethys is considered unlikely.[11]

The surface of Thesys is one of the most reflective (at visual wavelengths) in the solar system, with a visual albedo of 1.229. This very high albedo is the result of the sandblasting of particles from Saturn's E-ring, a faint ring composed of small, water-ice particles generated by Enceladus's south polar geysers.[5] The radar albedo of the Tethyan surface is also very high.[12] The surface of Tethys is composed from almost pure water ice with only small amount of a dark material. Its visible spectrum is flat and featureless, while in the near-infrared there are strong water ice absorption bands at 1.25, 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0 μm wavelengths.[13] No compound other than water ice has been unambiguously identified on Tethys. The dark material has the same spectral properties as one on the surfaces of the dark Saturnian moons—Iapetus and Hyperion. The most probable candidate is nanophase iron or hematite. Measurements of the thermal emission as well as radar observations by the Cassini spacecraft show that the icy regolith on the surface of Tethys is structurally complex[12] and has a large porosity exceeding 95%.[14]

Surface features

Two different types of terrain are found on Tethys, one composed of densely cratered regions and the other consisting of a dark colored and lightly cratered belt that extends across the moon. The light cratering of this second region indicates that Tethys was once internally active, causing parts of the older terrain to be resurfaced. The exact cause of the darkness of the belt is unknown but a possible interpretation comes from recent Galileo orbiter images of Jupiter's moons Ganymede and Callisto, both of which exhibit light polar caps that are made from bright ice deposits on pole-facing slopes of craters. From a distance the caps appear brighter due to the thousands of unresolved ice patches in small craters present there. The Tethyan surface may have been formed in a similar manner, consisting of hazy polar caps of unresolved bright ice patches with a darker zone in between.

The western hemisphere of Tethys is dominated by a huge impact crater called Odysseus, whose 400 km diameter is nearly 2/5 of that of Tethys itself. The crater is now quite flat (or more precisely, it conforms to Tethys' spherical shape), like the craters on Callisto, without the high ring mountains and central peaks commonly seen on the Moon and Mercury. This is most likely due to the slumping of the weak Tethyan icy crust over geologic time.

The second major feature seen on Tethys is a huge valley called Ithaca Chasma, 100 km wide and 3 to 5 km deep. It runs 2000 km long, approximately 3/4 of the way around Tethys' circumference. It is thought that Ithaca Chasma formed as Tethys' internal liquid water solidified, causing the moon to expand and cracking the surface to accommodate the extra volume within. The subsurface ocean may have resulted from a 2:3 orbital resonance between Dione and Tethys early in the solar system's history that led to orbital eccentricity and tidal heating of Tethys' interior. The ocean would have frozen after the moons escaped from the resonance.[15] Earlier craters that formed before Tethys solidified were probably all erased by geological activity before then. There is another theory about the formation of Ithaca Chasma: when the impact that caused the great crater Odysseus occurred, the shock wave traveled through Tethys and fractured the icy, brittle surface on the other side. The Tethyan surface temperature is -187°C.

Trojan moons

The co-orbital moons Telesto and Calypso are located within Tethys' Lagrangian points L4 and L5, 60 degrees ahead and behind Tethys in its orbit respectively.

Flybys

Voyager 2 took images of Tethys from 594,000 kilometers (368,000 miles) when it flew by the Saturn system in 1981. Closer flybys took place in the 2000s when Cassini probe went into orbit around Saturn.

The Cassini orbiter performed a close targeted flyby of Tethys on September 23, 2005 at the distance 1500 km. Cassini observed Tethys at moderate distances during its extended mission.

The Cassini orbiter performed a flyby of Tethys on August 14, 2010 photographing the second-largest crater on Tethys, Penelope, which is 150 km wide, at a distance of 38300 km.

Tethys in fiction

Notes

- ^ In US dictionary transcription, Template:USdict.

- ^ The masses of smaller spherical moons are (in kg): Enceladus—1.1×1020, Miranda—0.6×1020, Proteus—0.5×1020, Mimas—0.4×1020. The total mass of remaining moons is about 0.9×1020. So, the total mass of all moons smaller than Triton is about 3.5×1020. (See List of moons by diameter)

Citations

- ^ Jacobson, R.A. (2006) SAT252 (2007-06-28). "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". JPL/NASA. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b NASA Celestia

- ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/508812, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/508812instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1134681, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1134681instead. (supporting online material, table S1) - ^ "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ a b G.D. Cassini (1686–1692). "An Extract of the Journal Des Scavans. of April 22 st. N. 1686. Giving an account of two new Satellites of Saturn, discovered lately by Mr. Cassini at the Royal Observatory at Paris". Philosophical Transactions. 16: 79–85.

- ^ a b c Van Helden, Albert (1994). "Naming the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn" (PDF). The Newsletter of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society (32): 1–2.

- ^ Fred William Price - The planet observer's handbook - page 279

- ^ As reported by William Lassell, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43 (January 14, 1848)

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.02.019, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.02.019instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.001, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.001instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.008, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.008instead. - ^ Chen, E. M. A. (March 2008). "Thermal and Orbital Evolution of Tethys as Constrained by Surface Observations" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIX (2008). Retrieved 2008-03-14.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

References

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_18, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_18instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_19, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_19instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_20, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_20instead.

External links

- Tethys Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration Site

- Movie of Tethys' rotation by Calvin J. Hamilton (based on Voyager images)

- The Planetary Society: Tethys

- Cassini images of Tethys

- Images of Tethys at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- Movie of Tethys' rotation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Tethys basemaps (August 2010) from Cassini images

- Tethys atlas (August 2008) from Cassini images

- Tethys map with feature names from USGS Saturn system page