Inositol: Difference between revisions

m →Counter to road salt: punctuation correction |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 242: | Line 242: | ||

| doi = 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181e8e1b1 |

| doi = 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181e8e1b1 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

A recent Systematic review published by the Cochrane Collaboration has shown evidence that Inositol, in preterm babies who either have or are at a risk of developing respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)is effective in reducing adverse neonatal outcomes. <ref>{{Cite journal | author = Howlett A, Ohlsson A, Plakkal N. | title = Inositol in preterm infants at risk for or having respiratory distress syndrome. | journal = Cochrane Database Syst Rev | issue = 2 | pages = CD000366| year = 2015 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD000366.pub3}}</ref> |

|||

Animal studies suggest inositol reduces the severity of the [[osmotic demyelination syndrome]] if given before rapid correction of chronic [[hyponatraemia]].<ref>{{cite journal |

Animal studies suggest inositol reduces the severity of the [[osmotic demyelination syndrome]] if given before rapid correction of chronic [[hyponatraemia]].<ref>{{cite journal |

||

Revision as of 05:41, 6 February 2015

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(1R,2R,3S,4S,5R,6S)-cyclohexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol

| |

| Other names

cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-Cyclohexanehexol , Cyclohexanehexol,

Mouse antialopecia factor, Nucite, Phaseomannite, Phaseomannitol, Rat antispectacled eye factor, and Scyllite (for the structural isomer scyllo-Inositol) | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.027.295 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g/mol |

| Density | 1.752 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 225 to 227 °C (437 to 441 °F; 498 to 500 K) |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 143 °C (289 °F; 416 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Inositol or cyclohexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol is a chemical compound with formula Template:Carbon6Template:Hydrogen12Template:Oxygen6 or (-CHOH-)6, a six-fold alcohol (polyol) of cyclohexane. It exists in nine possible stereoisomers, of which the most prominent form, widely occurring in nature, is cis-1,2,3,5-trans-4,6-cyclohexanehexol, or myo-inositol (former names meso-inositol or i-inositol).[2][3] Inositol is a carbohydrate, though not a classical sugar. Its taste has been assayed at half the sweetness of table sugar (sucrose).[4][5]

myo-Inositol plays an important role as the structural basis for a number of secondary messengers in eukaryotic cells, the various inositol phosphates. In addition, inositol serves as an important component of the structural lipids phosphatidylinositol (PI) and its various phosphates, the phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) lipids.

Inositol or its phosphates and associated lipids are found in many foods, in particular fruit, especially cantaloupe and oranges.[6] In plants, the hexaphosphate of inositol, phytic acid or its salts, the phytates, are found. These serve as phosphate stores in the seed. Phytic acid occurs also in cereals with high bran content and also nuts and beans. Yet, inositol, when present as phytate, is not directly bioavailable to humans in the diet, since it is not digestible. Some food preparation techniques partly break down phytates to change this. Inositol as it occurs in certain plant-derived substances such as lecithins, however, is well-absorbed and relatively bioavailable.

myo-Inositol (free of phosphate) was once considered a member of the vitamin B complex; however, because it is produced by the human body from glucose, it is not an essential nutrient.[7] Some substances such as niacin can also be synthesized in the body, but are not made in amounts considered adequate for good health, thus are still classified as essential nutrients. However, no convincing evidence indicates this is the case for myo-inositol.

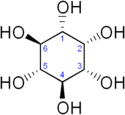

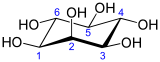

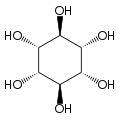

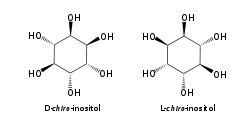

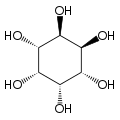

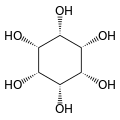

Isomers and structure

The isomer myo-inositol is a meso compound possessing an optically inactive plane of symmetry through the molecule, and meso-inositol is an obsolete name that refers to myo-inositol. Besides myo-inositol, the other naturally occurring stereoisomers (though in minimal quantities) are scyllo-, muco-, D-chiro-, and neo-inositol. The other possible isomers are L-chiro-, allo-, epi-, and cis-inositol. As their name denotes, the two chiro inositols are the only pair of inositol enantiomers, but they are enantiomers of each other, not of myo-inositol.

|

|

|

|

| myo- | scyllo- | muco- | chiro- |

|

|

|

|

| neo- | allo- | epi- | cis- |

In its most stable conformational geometry, the myo-inositol isomer assumes the chair conformation, which puts the maximum number of hydroxyls to the equatorial position, where they are farthest apart from each other. In this conformation, the natural myo isomer has a structure in which five of the six hydroxyls (the first, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth) are equatorial, whereas the second hydroxyl group is axial.[8]

Synthesis

myo-Inositol is synthesized from glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) in two steps. First, G-6-P is isomerised by an inositol-3-phosphate synthase enzyme (called ISYNA1) to myo-inositol 1-phosphate, which is then dephosphorylated by an inositol monophosphatase enzyme (called IMPase 1) to give free myo-inositol. In humans, most inositol is synthesized in the kidneys, in typical amounts of a few grams per day.[9]

Function

Inositol and some of its mono- and polyphosphates function as the basis for a number of signaling and secondary messenger molecules. They are involved in a number of biological processes, including:

- Insulin signal transduction[10]

- Cytoskeleton assembly

- Nerve guidance (epsin)

- Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentration control[11]

- Cell membrane potential maintenance[12]

- Breakdown of fats [13]

- Gene expression[14][15]

Phytic acid in plants

Phytic acid, which is inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6), also known as phytate when in salt form, is the principal storage form of phosphorus in many plant tissues, especially bran and seeds.[16] Neither the inositol nor the phosphate in phytic acid in plants is available to humans, or to animals that are not ruminants, since it cannot be broken down, except by bacteria. Moreover, phytic acid also chelates important minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc, making them unabsorbable, and contributing to mineral deficiencies in people whose diets rely highly on bran and seeds for their mineral intake, such as occurs in developing countries.[17][18]

Inositol penta- (IP5), tetra- (IP4), and triphosphate (IP3) are also called "phytates".

Explosive potential

At the 1936 meeting of the American Chemical Society, professor Edward Bartow of the University of Iowa presented a commercially viable means of extracting large amounts of inositol from the phytic acid naturally present in waste corn. As a possible use for the chemical, he suggested 'inositol nitrate' as a more stable alternative to nitroglycerin.[19] Today, inositol nitrate is used to gelatinize nitrocellulose, thus can be found in many modern explosives and solid rocket propellants.[20]

Counter to road salt

When plants are exposed to increasing concentrations of road salt, the plant cells become dysfunctional and undergo apoptosis, leading to an inhibition of growth in plants. Inositol pretreatment could reverse the effects of salt on plants.[21][22]

Clinical applications

Psychiatric conditions

Some preliminary results of studies on high-dose inositol supplements show promising results for people suffering from problems such as bulimia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), agoraphobia, and unipolar and bipolar depression.[23][24][25]

In a single double-blind study on 13 patients, myo-inositol (18 g daily) was found to reduce the symptoms of OCD significantly, with effectiveness equal to SSRIs and virtually without side effects.[26] In a double-blind, controlled trial, myo-inositol (18 grams daily) was superior to fluvoxamine for decreasing the number of panic attacks and other side effects.[23]

Similarly large doses of inositol have been studied for treatment of depression. A 2004 meta-analysis by randomized controlled trials, with mixed results. The authors concluded the evidence is insufficient to determine whether inositol treatment can reduce depression symptoms, but no evidence of harm or negative side effects is seen.[27]

Other studies suggest lithium treatment may further inhibit the enzyme inositol monophosphatase, leading to higher intracellular levels of inositol triphosphate,[28] an effect enhanced further by administration of an inositol triphosphate reuptake inhibitor.

Other conditions

D-chiro-Inositol (DCI) has been found in two double-blind studies to be an effective treatment for many of the clinical hallmarks of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), including insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism, and oligo-amenorrhea;[29][30] the impetuses for these studies were the observed defects in DCI metabolism in PCOS and the implication of DCI in insulin signal transduction.[10][31] Another small, placebo-controlled study has demonstrated that myo-inositol supplementation improves features of dysmetabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women, including triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and diastolic blood pressure.[32]

A recent Systematic review published by the Cochrane Collaboration has shown evidence that Inositol, in preterm babies who either have or are at a risk of developing respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)is effective in reducing adverse neonatal outcomes. [33]

Animal studies suggest inositol reduces the severity of the osmotic demyelination syndrome if given before rapid correction of chronic hyponatraemia.[34] Further study is required before its application in humans for this indication.

Studies from in vitro experiments, animal studies, and limited clinical experiences, claim that inositol may be used effectively against some types of cancer, in particular, when used in combination with phytic acid.[35]

Common use as a "cutting" agent

Inositol has been used as an adulterant (or cutting agent) in many illegal drugs, such as cocaine, methamphetamine, and sometimes heroin.[36] This use is presumed to be connected with one or more of the substance's properties of solubility, powdery texture, or reduced sweetness (50%) as compared with more common sugars.

Inositol is also used as a stand-in for cocaine on television and film.[37]

Nutritional sources

myo-Inositol is naturally present in a variety of foods, although tables of this do not always distinguish between the bioavailable lecithin form, and the unavailable phytate form in grains.[38] According to research, foods containing the highest concentrations of myo-inositol (including its compounds) include fruits, beans, grains, and nuts.[38] Beans and grains, however, as seeds, contain large amounts of inositol as phytate. Some energy drinks also contain inositol.

See also

References

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 4883.

- ^ Synonyms in PubChem

- ^ Synonyms in Commonchemistry.org

- ^ Chinese mfgr.

- ^ Another Chinese mfgr.

- ^ Clements RS Jr, Darnell B (1980). "Myo-inositol content of common foods: development of a high-myo-inositol diet" (PDF). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 33 (9): 1954–1967. PMID 7416064.

- ^ Reynolds, James E. F. (January 1, 1993). Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia. Vol. 30. Pennsylvania: Rittenhouse Book Distributors. p. 1379. ISBN 0-85369-300-5.

An isomer of glucose that has traditionally been considered to be a B vitamin although it has an uncertain status as a vitamin and a deficiency syndrome has not been identified in man

- ^ S. M. N. Furse (2006). The Chemical and Bio-physical properties of Phosphatidylinositol phosphates, Thesis for M.Res. Imperial College London.

- ^ Subcell Biochem. 2006;39:293-314. Mammalian inositol 3-phosphate synthase: its role in the biosynthesis of brain inositol and its clinical use as a psychoactive agent. Parthasarathy LK, Seelan RS, Tobias C, Casanova MF, Parthasarathy RN.

- ^ a b Larner J (2002). "D-chiro-inositol--its functional role in insulin action and its deficit in insulin resistance". Int J Exp Diabetes Res. 3 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1080/15604280212528. PMC 2478565. PMID 11900279.

- ^ Gerasimenko, Julia V; et al; “Bile Acids Induce Ca2+ Release from Both the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Acidic Intracellular Calcium Stores through Activation of Inositol Trisphosphate Receptors and Ryanodine Receptors”; Journal of Biological Chemistry; December 29, 2006; Volume 281: Pp 40154-40163.

- ^ Kukuljan M, Vergara L, Stojilkovic SS (February 1997). "Modulation of the kinetics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced [Ca2+]i oscillations by calcium entry in pituitary gonadotrophs". Biophysical Journal. 72 (2 Pt 1): 698–707. Bibcode:1997BpJ....72..698K. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78706-X. PMC 1185595. PMID 9017197.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rapiejko PJ, Northup JK, Evans T, Brown JE, Malbon CC (November 1986). "G-proteins of fat-cells. Role in hormonal regulation of intracellular inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate". The Biochemical Journal. 240 (1): 35–40. PMC 1147372. PMID 3103610.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shen, X.; Xiao, H; Ranallo, R; Wu, WH; Wu, C (2003). "Modulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes by inositol polyphosphates". Science. 299 (5603): 112–4. doi:10.1126/science.1078068. PMID 12434013.

- ^ Steger, D. J.; Haswell, ES; Miller, AL; Wente, SR; O'Shea, EK (2003). "Regulation of chromatin remodelling by inositol polyphosphates". Science. 299 (5603): 114–6. doi:10.1126/science.1078062. PMC 1458531. PMID 12434012.

- ^ Phytic acid

- ^ Hurrell RF (September 2003). "Influence of vegetable protein sources on trace element and mineral bioavailability". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (9): 2973S–7S. PMID 12949395.

- ^ Committee on Food Protection, Food and Nutrition Board, National Research Council (1973). "Phytates". Toxicants Occurring Naturally in Foods. National Academy of Sciences. pp. 363–371. ISBN 978-0-309-02117-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Laurence, William L. "Corn by-product yields explosive", The New York Times. April 17, 1936. Page 7.

- ^ Ledgard, Jared. The Preparatory Manual of Explosives, 2007. p. 366.

- ^ Chaterjee, J.; Mujumder, AL. (September 2010). "Salt-induced abnormalities on root tip mitotic cells of Allium cepa: prevention by inositol pretreatment". 245 ((1-4)): 165-72. doi:10.1007/s00709-010-0170-4. PMID 20559853. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Theerakulpisut, P.; Gunnula, W. (2012). "Exogenous Sorbitol and Trehalose Mitigated Salt Stress Damage in Salt-sensitive but not Salt-tolerant Rice Seedlings". Asian Journal of Crop Science. 4: 165–170. doi:10.3923/ajcs.2012.165.170. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ^ a b Palatnik A, Frolov K, Fux M, Benjamin J (2001). "Double-blind, controlled, crossover trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (3): 335–339. doi:10.1097/00004714-200106000-00014. PMID 11386498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine J, Barak Y, Gonzalves M, Szor H, Elizur A, Kofman O, Belmaker RH. (1995). "Double-blind, controlled trial of inositol treatment of depression". American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (5): 792–794. PMID 7726322.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine J (1997). "Controlled trials of inositol in psychiatry". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 7 (May, 7): 147–55. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(97)00409-4. PMID 9169302.

- ^ Fux M, Levine J, Aviv A, Belmaker RH (1996). "Inositol treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry. 153 (9): 1219–21. PMID 8780431.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor MJ, Wilder H, Bhagwagar Z, Geddes J (2004). Taylor, Matthew J (ed.). "Inositol for depressive disorders". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004049. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004049.pub2. PMID 15106232.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Einat H, Kofman O, Itkin O, Lewitan RJ, Belmaker RH (1998). "Augmentation of lithium's behavioral effect by inositol uptake inhibitors". J Neural Transm. 105 (1): 31–8. doi:10.1007/s007020050035. PMID 9588758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nestler J E, Jakubowicz D J, Reamer P, Gunn R D, Allan G (1999). "Ovulatory and metabolic effects of D-chiro-inositol in the polycystic ovary syndrome". N Engl J Med. 340 (17): 1314–1320. doi:10.1056/NEJM199904293401703. PMID 10219066.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iuorno M J, Jakubowicz D J, Baillargeon J P, Dillon P, Gunn R D, Allan G, Nestler J E (2002). "Effects of d-chiro-inositol in lean women with the polycystic ovary syndrome". Endocr Pract. 8 (6): 417–423. doi:10.4158/EP.8.6.417. PMID 15251831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nestler J E, Jakubowicz D J, Iuorno M J (2000). "Role of inositolphosphoglycan mediators of insulin action in the polycystic ovary syndrome". J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 13 Suppl 5: 1295–1298. PMID 11117673.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Giordano D, Corrado F, Santamaria A, Quattrone S, Pintaudi B, DiBenedetto A, D’Anna R (2011). "Effects of myo-inositol supplementation in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome: a perspective, randomized, placebo-controlled study". Menopause: the Journal of the North American Menopause Society. 18 (1): 102–104. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181e8e1b1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Howlett A, Ohlsson A, Plakkal N. (2015). "Inositol in preterm infants at risk for or having respiratory distress syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD000366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000366.pub3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silver SM, Schroeder BM, Sterns RH, Rojiani AM (2006). "Myoinositol administration improves survival and reduces myelinolysis after rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia in rats". J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 65 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1097/01.jnen.0000195938.02292.39. PMID 16410747.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vucenik, I; Shamsuddin, AM (2003). "Cancer inhibition by inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) and inositol: from laboratory to clinic". The Journal of nutrition. 133 (11 Suppl 1): 3778S–3784S. PMID 14608114.

- ^ http://feedadditivechina.com/6-16-inositol.html

- ^ Golianopoulos, Thomas. "Drug Doubles: What Actors Actually Toke, Smoke and Snort on Camera". Wired Magazine. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b Clements, Rex; Betty Darnell (1980). "Myo-inositol content of common foods: development of a high-myo-inositol diet" (PDF). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 33 (9): 1954–1967. PMID 7416064. Retrieved 2009-05-18.