Dog behavior: Difference between revisions

→Reproduction: Additional information on this citation. The second citation was removed as it added nothing extra. |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m [579]Alter: title, authors. Add: display-authors, pages, doi_brokendate, displayauthors, bibcode, volume, doi, pmid, issue, author pars. 1-5. Removed redundant parameters. You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

====Dog-dog==== |

====Dog-dog==== |

||

[[Image:Labradorský Retrívr.jpg|thumb|300px|Playtime]] |

[[Image:Labradorský Retrívr.jpg|thumb|300px|Playtime]] |

||

Play between dogs usually involves several behaviours that are often seen in aggressive encounters, for example, nipping, biting, growling and biting. It is therefore important for the dogs to place these behaviours in the context of play, rather than aggression. Dogs signal their intent to play with a range of behaviours including a "play-bow", "face-paw" "open-mouthed play face" and postures inviting the other dog to chase the initiator. Similar signals are given throughout the play bout to maintain the context of the potentially aggressive activities.<ref name="Horowitz">{{cite journal|title=Attention to attention in domestic dog ''Canis familiaris'' dyadic play |

Play between dogs usually involves several behaviours that are often seen in aggressive encounters, for example, nipping, biting, growling and biting. It is therefore important for the dogs to place these behaviours in the context of play, rather than aggression. Dogs signal their intent to play with a range of behaviours including a "play-bow", "face-paw" "open-mouthed play face" and postures inviting the other dog to chase the initiator. Similar signals are given throughout the play bout to maintain the context of the potentially aggressive activities.<ref name="Horowitz">{{cite journal|title=Attention to attention in domestic dog ''Canis familiaris'' dyadic play|author=Horowitz, A.|year=2009|journal=Animal Cognition|volume=12|issue=1|pages=107–118|pmid=18679727|doi=10.1007/s10071-008-0175-y}}</ref> |

||

From a young age, dogs engage in play with one another. Dog play is made up primarily of mock fights. It is believed that this behavior, which is most common in puppies, is training for important behaviors later in life. Play between puppies is not necessarily a 50:50 symmetry of dominant and submissive roles between the individuals; dogs who engage in greater rates of dominant behaviours (e.g. chasing, forcing partners down) at later ages also initiate play at higher rates. This could imply that winning during play becomes more important as puppies mature.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Partner preferences and asymmetries in social play among domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, littermates|author=Ward, C., Bauer, E.B. and Smuts, B.B.|journal=Animal Behaviour|volume=76|issue=4|year=2008|pages=1187–1199| |

From a young age, dogs engage in play with one another. Dog play is made up primarily of mock fights. It is believed that this behavior, which is most common in puppies, is training for important behaviors later in life. Play between puppies is not necessarily a 50:50 symmetry of dominant and submissive roles between the individuals; dogs who engage in greater rates of dominant behaviours (e.g. chasing, forcing partners down) at later ages also initiate play at higher rates. This could imply that winning during play becomes more important as puppies mature.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Partner preferences and asymmetries in social play among domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, littermates|author=Ward, C., Bauer, E.B. and Smuts, B.B.|journal=Animal Behaviour|volume=76|issue=4|year=2008|pages=1187–1199|doi=10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.06.004}}</ref> |

||

====Dog-human==== |

====Dog-human==== |

||

The motivation for a dog to play with another dog is distinct from that of a dog playing with a human. Dogs walked together with opportunities to play with one another, play with their owners with the same frequency as dogs being walked alone. Dogs in households with two or more dogs play more often with their owners than dogs in households with a single dog, indicating the motivation to play with other dogs does not substitute for the motivation to play with humans.<ref name="Rooney">{{cite journal|title=A comparison of dog–dog and dog–human play behaviour.|author=Rooney, N.J., Bradshaw, J.W.S. and Robinson, I.H.|journal=Applied Animal Behaviour Science|volume= 66|issue=3|year=2000|pages=235–248}}</ref> |

The motivation for a dog to play with another dog is distinct from that of a dog playing with a human. Dogs walked together with opportunities to play with one another, play with their owners with the same frequency as dogs being walked alone. Dogs in households with two or more dogs play more often with their owners than dogs in households with a single dog, indicating the motivation to play with other dogs does not substitute for the motivation to play with humans.<ref name="Rooney">{{cite journal|title=A comparison of dog–dog and dog–human play behaviour.|author=Rooney, N.J., Bradshaw, J.W.S. and Robinson, I.H.|journal=Applied Animal Behaviour Science|volume= 66|issue=3|year=2000|pages=235–248}}</ref> |

||

It is a common misconception that winning and losing games such as "tug-of-war" and "rough-and-tumble" can can influence a dog's dominance relationship with humans. Rather, the way in which dogs play indicates their temperament and relationship with their owner. Dogs that play rough-and-tumble are more amenable and show lower separation anxiety than dogs which play other types of games, and dogs playing tug-of-war and "fetch" are more confident. Dogs which start the majority of games are less amenable and more likely to be aggressive.<ref>{{cite journal| |

It is a common misconception that winning and losing games such as "tug-of-war" and "rough-and-tumble" can can influence a dog's dominance relationship with humans. Rather, the way in which dogs play indicates their temperament and relationship with their owner. Dogs that play rough-and-tumble are more amenable and show lower separation anxiety than dogs which play other types of games, and dogs playing tug-of-war and "fetch" are more confident. Dogs which start the majority of games are less amenable and more likely to be aggressive.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1207/S15327604JAWS0602_01|pmid=12909524|author=Rooney, N.J. and Bradshaw, Jv.W.S.|pages=67–94|title=Links between play and dominance and attachment dimensions of dog-human relationships|journal=Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science|volume=6|issue=2|year=2003}}</ref> |

||

Playing with humans can affect the [[cortisol]] levels of dogs. In one study, the cortisol responses of police dogs and border guard dogs was assessed after playing with their handlers. The cortisol concentrations of the police dogs increased, whereas the border guard dogs' hormone levels decreased. The researchers noted that during the play sessions, police officers were disciplining their dogs, whereas the border guards were truly playing with them, i.e. this included bonding and affectionate behaviours. They commented that several studies have shown that behaviours associated with control, authority or aggression increase cortisol, whereas play and affiliative behaviour decrease cortisol levels.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Hormones and Behavior|volume=54|issue=1|year=2008|pages=107–114|title=Affiliative and disciplinary behavior of human handlers during play with their dog affects cortisol concentrations in opposite directions |

Playing with humans can affect the [[cortisol]] levels of dogs. In one study, the cortisol responses of police dogs and border guard dogs was assessed after playing with their handlers. The cortisol concentrations of the police dogs increased, whereas the border guard dogs' hormone levels decreased. The researchers noted that during the play sessions, police officers were disciplining their dogs, whereas the border guards were truly playing with them, i.e. this included bonding and affectionate behaviours. They commented that several studies have shown that behaviours associated with control, authority or aggression increase cortisol, whereas play and affiliative behaviour decrease cortisol levels.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Hormones and Behavior|volume=54|issue=1|year=2008|pages=107–114|title=Affiliative and disciplinary behavior of human handlers during play with their dog affects cortisol concentrations in opposite directions|author=Horváth, Z., Dóka, A. and Miklósi A.|pmid=18353328|doi=10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.002}}</ref> |

||

===Empathy=== |

===Empathy=== |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

==Behavior problems== |

==Behavior problems== |

||

A survey of 203 dog owners in Melbourne, Australia, found that the main behaviour problems reported by owners were overexcitement (63%) and jumping up on people (56%).<ref name="Kobelt">{{cite journal|journal=Applied Animal Behaviour Science|volume=82|issue=2|year=2003|pages=137–148|title=A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia—conditions and behaviour problems |

A survey of 203 dog owners in Melbourne, Australia, found that the main behaviour problems reported by owners were overexcitement (63%) and jumping up on people (56%).<ref name="Kobelt">{{cite journal|journal=Applied Animal Behaviour Science|volume=82|issue=2|year=2003|pages=137–148|title=A survey of dog ownership in suburban Australia—conditions and behaviour problems|author=Kobelt, A.J., Hemsworth, P.H., Barnett, J.L. and Coleman, G.J.|doi=10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00062-5}}</ref> |

||

===Separation anxiety=== |

===Separation anxiety=== |

||

When dogs are separated from humans, usually the owner, they often display behaviours such as |

When dogs are separated from humans, usually the owner, they often display behaviours such as |

||

destructiveness, faecal or urinary elimination, hypersalivation or vocalisation. Dogs from single-owner homes are approximately 2.5 times more likely to have separation anxiety compared to dogs from multiple-owner homes. Furthermore, sexually intact dogs are only one third as likely to have separation anxiety as neutered dogs. The sex of dogs and whether there is another pet in the home do not have an affect on separation anxiety.<ref name="Flannigan">{{cite journal|journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|year=2001|volume=219|issue=4|pages=460–466| |

destructiveness, faecal or urinary elimination, hypersalivation or vocalisation. Dogs from single-owner homes are approximately 2.5 times more likely to have separation anxiety compared to dogs from multiple-owner homes. Furthermore, sexually intact dogs are only one third as likely to have separation anxiety as neutered dogs. The sex of dogs and whether there is another pet in the home do not have an affect on separation anxiety.<ref name="Flannigan">{{cite journal|journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|year=2001|volume=219|issue=4|pages=460–466|doi=10.2460/javma.2001.219.460|pmid=11518171|title=Risk factors and behaviors associated with separation anxiety in dogs|author=Flannigan, G. and Dodman, N.H.A}}</ref> |

||

===Tail chasing=== |

===Tail chasing=== |

||

Tail chasing can be classified as a [[stereotypy]]. |

Tail chasing can be classified as a [[stereotypy]]. |

||

In one clinical study on the behaval problem, 18 tail-chasing [[terrier]]s were given [[clomipramine]] orally at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/kg (0.5 to 0.9 mg/lb) of body weight, every 12 hours. Three of the dogs required treatment at a slightly higher dosage range to control tail chasing, however, after 1 to 12 weeks of treatment, 9 of 12 dogs were reported to have a 75% or greater reduction in tail chasing.<ref name="Moon">{{cite journal|author=Moon-Fanelli, A.A. and Dodman, N.H.|year=1998|journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|volume=212|issue=8|pages=1252–1257|title=Description and development of compulsive tail chasing in terriers and response to clomipramine treatment |

In one clinical study on the behaval problem, 18 tail-chasing [[terrier]]s were given [[clomipramine]] orally at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/kg (0.5 to 0.9 mg/lb) of body weight, every 12 hours. Three of the dogs required treatment at a slightly higher dosage range to control tail chasing, however, after 1 to 12 weeks of treatment, 9 of 12 dogs were reported to have a 75% or greater reduction in tail chasing.<ref name="Moon">{{cite journal|author=Moon-Fanelli, A.A. and Dodman, N.H.|year=1998|journal=Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association|volume=212|issue=8|pages=1252–1257|title=Description and development of compulsive tail chasing in terriers and response to clomipramine treatment|pmid=9569164}}</ref> |

||

==Behavior compared to other canids== |

==Behavior compared to other canids== |

||

| Line 206: | Line 206: | ||

<ref name=coren2004>{{Cite book|title = How Dogs Think|author=Coren, Stanley|publisher=First Free Press, Simon & Schuster |year = 2004|isbn = 0-7432-2232-6}}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> |

<ref name=coren2004>{{Cite book|title = How Dogs Think|author=Coren, Stanley|publisher=First Free Press, Simon & Schuster |year = 2004|isbn = 0-7432-2232-6}}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=cunningham1905>{{cite doi|10.1017/S0370164600016667}}</ref> |

<ref name=cunningham1905>{{cite doi|10.1017/S0370164600016667}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=custance2012>{{cite journal|last=Custance|first=D|last2=Mayer|first2=J| year=2012 |title=Empathic-like responding by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to distress in humans: an exploratory study|journal=Anim Cogn. |pages=851–9 |doi=10.1007/s10071-012-0510-1|url=http://www.academia.edu/1632457/Empathic-like_responding_by_domestic_dogs_Canis_familiaris_to_distress_in_humans_an_exploratory_study}}</ref> |

<ref name=custance2012>{{cite journal|last=Custance|first=D|last2=Mayer|first2=J| year=2012 |title=Empathic-like responding by domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to distress in humans: an exploratory study|journal=Anim Cogn. |volume=15|issue=5|pages=851–9 |doi=10.1007/s10071-012-0510-1|pmid=22644113|url=http://www.academia.edu/1632457/Empathic-like_responding_by_domestic_dogs_Canis_familiaris_to_distress_in_humans_an_exploratory_study}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=drews1993>Drews, C., 1993. The concept and definition of dominance in animal behaviour. Behaviour. 125, 283-313</ref> |

<ref name=drews1993>Drews, C., 1993. The concept and definition of dominance in animal behaviour. Behaviour. 125, 283-313</ref> |

||

<ref name=feuerbacker2015>{{cite DOI|10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.019}}</ref> |

<ref name=feuerbacker2015>{{cite DOI|10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.019}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=fonberg1981>{{cite PMID|7329743}}</ref> |

<ref name=fonberg1981>{{cite PMID|7329743}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=frank1982>{{cite journal | author1 = Frank H | author2 = Frank MG | date= 1982 | title= On the effects of domestication on canine social development and behavior | journal= Applied Animal Ethology | volume= 8 | issue = 6 | pages= 507–525 | doi= 10.1016/0304-3762(82)90215-2}}</ref> |

<ref name=frank1982>{{cite journal | author1 = Frank H | author2 = Frank MG | date= 1982 | title= On the effects of domestication on canine social development and behavior | journal= Applied Animal Ethology | volume= 8 | issue = 6 | pages= 507–525 | doi= 10.1016/0304-3762(82)90215-2}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=freedman1960>{{cite journal|authors=Freedman, D. G., King, J. A., & Elliot, O.|year=1960|title=Critical period in the social development of dogs|journal=Science|volume=133|pages=1016–1017}}</ref> |

<ref name=freedman1960>{{cite journal|authors=Freedman, D. G., King, J. A., & Elliot, O.|year=1960|title=Critical period in the social development of dogs|journal=Science|volume=133|issue=3457|pages=1016–1017|bibcode=1961Sci...133.1016F|author1=Freedman|first1=Daniel G.|last2=King|first2=John A.|last3=Elliot|first3=Orville|doi=10.1126/science.133.3457.1016|pmid=13701603}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=freedman2014>{{cite journal | last=Freedman | first=Adam H. | last2=Gronau | first2=Ilan | last3=Schweizer | first3=Rena M. | last4=Ortega-Del Vecchyo | first4=Diego | last5=Han | first5=Eunjung | last6=Silva | first6=Pedro M. | last7=Galaverni | first7=Marco | last8=Fan | first8=Zhenxin | last9=Marx | first9=Peter | last10=Lorente-Galdos | first10=Belen | last11=Beale | first11=Holly | last12=Ramirez | first12=Oscar | last13=Hormozdiari | first13=Farhad | last14=Alkan | first14=Can | last15=Vilà | first15=Carles | last16=Squire | first16=Kevin | last17=Geffen | first17=Eli | last18=Kusak | first18=Josip | last19=Boyko | first19=Adam R. | last20=Parker | first20=Heidi G. | last21=Lee | first21=Clarence | last22=Tadigotla | first22=Vasisht | last23=Siepel | first23=Adam | last24=Bustamante | first24=Carlos D. | last25=Harkins | first25=Timothy T. | last26=Nelson | first26=Stanley F. | last27=Ostrander | first27=Elaine A. | last28=Marques-Bonet | first28=Tomas | last29=Wayne | first29=Robert K. | last30=Novembre | first30=John | date=16 January 2014 | title=Genome Sequencing Highlights Genes Under Selection and the Dynamic Early History of Dogs | url=http://www.plosgenetics.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pgen.1004016 | journal=PLOS Genetics | volume=10 | issue=1 | pages=e1004016 | publisher=PLOS Org | doi=10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016 | pmid=24453982 | pmc=3894170 | accessdate=December 8, 2014}}</ref> |

<ref name=freedman2014>{{cite journal | last=Freedman | first=Adam H. | last2=Gronau | first2=Ilan | last3=Schweizer | first3=Rena M. | last4=Ortega-Del Vecchyo | first4=Diego | last5=Han | first5=Eunjung | last6=Silva | first6=Pedro M. | last7=Galaverni | first7=Marco | last8=Fan | first8=Zhenxin | last9=Marx | first9=Peter | last10=Lorente-Galdos | first10=Belen | last11=Beale | first11=Holly | last12=Ramirez | first12=Oscar | last13=Hormozdiari | first13=Farhad | last14=Alkan | first14=Can | last15=Vilà | first15=Carles | last16=Squire | first16=Kevin | last17=Geffen | first17=Eli | last18=Kusak | first18=Josip | last19=Boyko | first19=Adam R. | last20=Parker | first20=Heidi G. | last21=Lee | first21=Clarence | last22=Tadigotla | first22=Vasisht | last23=Siepel | first23=Adam | last24=Bustamante | first24=Carlos D. | last25=Harkins | first25=Timothy T. | last26=Nelson | first26=Stanley F. | last27=Ostrander | first27=Elaine A. | last28=Marques-Bonet | first28=Tomas | last29=Wayne | first29=Robert K. | last30=Novembre | first30=John | date=16 January 2014 | title=Genome Sequencing Highlights Genes Under Selection and the Dynamic Early History of Dogs | url=http://www.plosgenetics.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pgen.1004016 | journal=PLOS Genetics | volume=10 | issue=1 | pages=e1004016 | publisher=PLOS Org | doi=10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016 | pmid=24453982 | pmc=3894170 | accessdate=December 8, 2014}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=gacsi2009>{{cite journal|authors=Gácsi, M., Gyori, B., Viranyi, Z., Kubinyi, E., Range, F., Belenyi, B. |

<ref name=gacsi2009>{{cite journal|authors=Gácsi, M., Gyori, B., Viranyi, Z., Kubinyi, E., Range, F., Belenyi, B.|year=2009|title=Explaining dog wolf differences in utilizing human pointing gestures: Selection for synergistic shifts in the development of some social skills|journal=PLoS ONE|volume=4(8)|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.00006584|author2=and others|displayauthors=1|doi_brokendate=2015-06-07}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=hare2002>{{Cite doi|10.1126/science.1072702}}</ref> |

<ref name=hare2002>{{Cite doi|10.1126/science.1072702}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=hare2005>Hare B, Tomasello M (2005) Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends Cogn Sci 9: 439–444</ref> |

<ref name=hare2005>Hare B, Tomasello M (2005) Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends Cogn Sci 9: 439–444</ref> |

||

<ref name=Hart2014>{{cite doi|10.1186/1742-9994-10-80}}</ref> |

<ref name=Hart2014>{{cite doi|10.1186/1742-9994-10-80}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Head>{{cite journal|title=Spatial learning and memory as a function of age in the dog |

<ref name=Head>{{cite journal|title=Spatial learning and memory as a function of age in the dog|author=Head, E., Mehta, R., Hartley, J., Kameka, M., Cummings, B.J., Cotman, C.W., Ruehl, W.W. and Milgram, N.W.|journal=Behavioral Neuroscience|volume=109|issue=5|year=1995|pages=851–858|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7044.109.5.851|doi=10.1037/0735-7044.109.5.851|pmid=8554710}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=kaminski2004>{{cite journal| |

<ref name=kaminski2004>{{cite journal|doi=10.1126/science.1097859|pmid=15192233|pages=1682–1683|year=2004|volume=304|issue=5677|journal=Science|author=Kaminski, J., Call, J. and Fischer, J.|title=Word learning in a domestic dog: Evidence for "fast mapping"|bibcode=2004Sci...304.1682K}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Kaulfub2008>{{cite journal|title=Neophilia in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and its implication for studies of dog cognition |

<ref name=Kaulfub2008>{{cite journal|title=Neophilia in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and its implication for studies of dog cognition|author=Kaulfuß, P. and Mills, D.S.|journal=Animal Cognition|year=2008|volume=11|issue=3|pages=553–556|pmid=18183436|doi=10.1007/s10071-007-0128-x}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=kleiman1981>Kleiman, D. G., & Malcolm, J. R., 1981. The evolution of male parental investment in mammals. Pages 347-387 in D. J. Gubernick and P. H. Klopfer, Eds., Parental care in mammals. Plenum Press, New York.</ref> |

<ref name=kleiman1981>Kleiman, D. G., & Malcolm, J. R., 1981. The evolution of male parental investment in mammals. Pages 347-387 in D. J. Gubernick and P. H. Klopfer, Eds., Parental care in mammals. Plenum Press, New York.</ref> |

||

<ref name=klinghammer1987>{{cite book|author=Klinghammer, E., & Goodmann, P. A.|year=1987|chapter=Socialization and management of wolves in captivity|editor=H. Frank|title=Man and wolf: Advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research|publisher=Dordrecht: W. Junk}}</ref> |

<ref name=klinghammer1987>{{cite book|author=Klinghammer, E., & Goodmann, P. A.|year=1987|chapter=Socialization and management of wolves in captivity|editor=H. Frank|title=Man and wolf: Advances, issues, and problems in captive wolf research|publisher=Dordrecht: W. Junk}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=levitis2009>{{cite journal|last=Levitis|first=Daniel| |

<ref name=levitis2009>{{cite journal|last=Levitis|first=Daniel|author2=William Z. Lidicker, Jr, Glenn Freund|title=Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour|journal=Animal Behaviour|date=June 2009|volume=78|pages=103–10|doi=10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018 |url=http://academic.reed.edu/biology/courses/bio342/2010_syllabus/2010_readings/levitis_etal_2009.pdf|last3=Freund|first3=Glenn}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=lord2013>{{cite doi|10.1111/eth.12044}}</ref> |

<ref name=lord2013>{{cite doi|10.1111/eth.12044}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=macdonald1995>Macdonald DW, Carr GM: Variation in dog society: between resource dispersion and social flux. In The Domestic Dog, Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Edited by Serpell J. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995:199-216</ref> |

<ref name=macdonald1995>Macdonald DW, Carr GM: Variation in dog society: between resource dispersion and social flux. In The Domestic Dog, Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Edited by Serpell J. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995:199-216</ref> |

||

<ref name=mcintire1967>{{cite journal|authors=McIntire, R., & Colley, T. A.|year=1967|title=Social reinforcement in the dog|journal=Psychological Reports|volume=20|pages=843–846}}</ref> |

<ref name=mcintire1967>{{cite journal|authors=McIntire, R., & Colley, T. A.|year=1967|title=Social reinforcement in the dog|journal=Psychological Reports|volume=20|issue=3|pages=843–846|pmid=6042498|author1=McIntire|first1=R. W.|last2=Colley|first2=T. A.|doi=10.2466/pr0.1967.20.3.843}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=mech1970>Mech, L. D. 1970. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. Natural History Press (Doubleday Publishing Co., N.Y.) 389 pp. (Reprinted in paperback by University of Minnesota Press, May 1981)</ref> |

<ref name=mech1970>Mech, L. D. 1970. The Wolf: The Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species. Natural History Press (Doubleday Publishing Co., N.Y.) 389 pp. (Reprinted in paperback by University of Minnesota Press, May 1981)</ref> |

||

<ref name=Mendl2010>{{cite journal|author= Mendl, M., Brooks, J., Basse, C., Burman, O., Paul, E., Blackwell, E. and Casey, R.|title=Dogs showing separation-related behaviour exhibit a ‘pessimistic’ cognitive bias|journal=Current Biology|volume=20|issue=19|year=2010|url=http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0960982210010201/1-s2.0-S0960982210010201-main.pdf?_tid=dca3e6e0-ad47-11e4-bc9f-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1423148668_0e54a842bf173b32ae557174ec0bb5f2}}</ref> |

<ref name=Mendl2010>{{cite journal|author= Mendl, M., Brooks, J., Basse, C., Burman, O., Paul, E., Blackwell, E. and Casey, R.|title=Dogs showing separation-related behaviour exhibit a ‘pessimistic’ cognitive bias|journal=Current Biology|volume=20|issue=19|year=2010|url=http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0960982210010201/1-s2.0-S0960982210010201-main.pdf?_tid=dca3e6e0-ad47-11e4-bc9f-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1423148668_0e54a842bf173b32ae557174ec0bb5f2}}</ref> |

||

| Line 234: | Line 234: | ||

<ref name=pongracz2012>Péter Pongrácz, Petra Bánhegyi and Ádám Miklósi (2012) When rank counts—dominant dogs learn better from a human demonstrator in a two-action test — Behaviour 149 (2012) 111–132</ref> |

<ref name=pongracz2012>Péter Pongrácz, Petra Bánhegyi and Ádám Miklósi (2012) When rank counts—dominant dogs learn better from a human demonstrator in a two-action test — Behaviour 149 (2012) 111–132</ref> |

||

<ref name=Prynne>{{cite web|author=Prynne, M.|title=Dog attack laws and statistics|publisher=The Telegraph|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/10429862/Dog-attack-laws-and-statistics.html|accessdate=April 14, 2015}}</ref> |

<ref name=Prynne>{{cite web|author=Prynne, M.|title=Dog attack laws and statistics|publisher=The Telegraph|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/10429862/Dog-attack-laws-and-statistics.html|accessdate=April 14, 2015}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=range2011>{{cite journal|authors=Range, F., & Virányi, Z.|year=2011|title=Development of gaze following abilities in wolves (Canis lupus)|journal=PloS One|volume=6(2)|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0016888}}</ref> |

<ref name=range2011>{{cite journal|authors=Range, F., & Virányi, Z.|year=2011|title=Development of gaze following abilities in wolves (Canis lupus)|journal=PloS One|volume=6(2)|issue=2|pages=e16888|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0016888|last1=Range|first1=Friederike|last2=Virányi|first2=Zsófia|bibcode=2011PLoSO...616888R}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Sacks>{{cite journal|journal=JAVMA|author=Sacks, J.J.|title=Breeds of dogs involved in fatal human attacks|pages=836–840|volume=217|issue=6|year=2000|url=http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/images/dogbreeds-a.pdf|accessdate=April 14, 2015}}</ref> |

<ref name=Sacks>{{cite journal|journal=JAVMA|author=Sacks, J.J.|title=Breeds of dogs involved in fatal human attacks|pages=836–840|volume=217|issue=6|year=2000|url=http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/images/dogbreeds-a.pdf|accessdate=April 14, 2015|pmid=10997153|last2=Sinclair|first2=L|last3=Gilchrist|first3=J|last4=Golab|first4=G. C.|last5=Lockwood|first5=R}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=scott1973>http://www.jstor.org/stable/3800116</ref> |

<ref name=scott1973>http://www.jstor.org/stable/3800116</ref> |

||

<ref name=seal1983>http://www.jstor.org/stable/3808606</ref> |

<ref name=seal1983>http://www.jstor.org/stable/3808606</ref> |

||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

<ref name=shipman2011>Shipman P (2011) The Animal Connection. A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human. New York: W.W. Norton and Co</ref> |

<ref name=shipman2011>Shipman P (2011) The Animal Connection. A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human. New York: W.W. Norton and Co</ref> |

||

<ref name=teglas2012>Teglas E, Gergely A, Kupan K, Miklosi A, Topal J (2012) Dogs' gaze following is tuned to human communicative signals. Current Biology 22: 209–212</ref> |

<ref name=teglas2012>Teglas E, Gergely A, Kupan K, Miklosi A, Topal J (2012) Dogs' gaze following is tuned to human communicative signals. Current Biology 22: 209–212</ref> |

||

<ref name=thalmann2013>{{cite journal | last=Thalmann | first=O. | last2=Shapiro | first2=B. | last3=Cui | first3=P. | last4=Schuenemann | first4=V.J. | last5=Sawyer | first5=S.K. | last6=Greenfield | first6=D.L. | last7=Germonpré | first7=M.B. | last8=Sablin | first8=M.V. | last9=López-Giráldez | first9=F. | last10=Domingo-Roura | first10=X. | last11=Napierala | first11=H. | last12=Uerpmann | first12=H-P. | last13=Loponte | first13=D.M. | last14=Acosta | first14=A.A. | last15=Giemsch | first15=L. | last16=Schmitz | first16=R.W. | last17=Worthington | first17=B. | last18=Buikstra | first18=J.E. | last19=Druzhkova | first19=A.S. | last20=Graphodatsky | first20=A.S. | last21=Ovodov | first21=N.D. | last22=Wahlberg | first22=N. | last23=Freedman | first23=A.H. | last24=Schweizer | first24=R.M. | last25=Koepfli | first25=K.-P. | last26=Leonard | first26=J.A. | last27=Meyer | first27=M. | last28=Krause | first28=J. | last29=Pääbo | first29=S. | last30=Green | first30=R.E. |last31=Wayne | first31=Robert K. | date=15 November 2013 | title=Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs | url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6160/871 | journal=Science | volume=342 | issue=6160 | pages=871–874 | publisher=AAAS | doi=10.1126/science.1243650 | accessdate=24 December 2014}}</ref> |

<ref name=thalmann2013>{{cite journal | last=Thalmann | first=O. | last2=Shapiro | first2=B. | last3=Cui | first3=P. | last4=Schuenemann | first4=V.J. | last5=Sawyer | first5=S.K. | last6=Greenfield | first6=D.L. | last7=Germonpré | first7=M.B. | last8=Sablin | first8=M.V. | last9=López-Giráldez | first9=F. | last10=Domingo-Roura | first10=X. | last11=Napierala | first11=H. | last12=Uerpmann | first12=H-P. | last13=Loponte | first13=D.M. | last14=Acosta | first14=A.A. | last15=Giemsch | first15=L. | last16=Schmitz | first16=R.W. | last17=Worthington | first17=B. | last18=Buikstra | first18=J.E. | last19=Druzhkova | first19=A.S. | last20=Graphodatsky | first20=A.S. | last21=Ovodov | first21=N.D. | last22=Wahlberg | first22=N. | last23=Freedman | first23=A.H. | last24=Schweizer | first24=R.M. | last25=Koepfli | first25=K.-P. | last26=Leonard | first26=J.A. | last27=Meyer | first27=M. | last28=Krause | first28=J. | last29=Pääbo | first29=S. | last30=Green | first30=R.E. |last31=Wayne | first31=Robert K. | date=15 November 2013 | title=Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs | url=http://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6160/871 | journal=Science | volume=342 | issue=6160 | pages=871–874 | publisher=AAAS | doi=10.1126/science.1243650 | pmid=24233726 | accessdate=24 December 2014| bibcode=2013Sci...342..871T | display-authors=29 }}</ref> |

||

<ref name=tomasello2009>{{cite doi|10.1126/science.1179670}}</ref> |

<ref name=tomasello2009>{{cite doi|10.1126/science.1179670}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=topal997>{{cite journal|author=Topál, J., Miklósi, Á. and Csányi, V.|year=1997|title=Dog-human relationship affects problem solving behavior in the dog |

<ref name=topal997>{{cite journal|author=Topál, J., Miklósi, Á. and Csányi, V.|year=1997|title=Dog-human relationship affects problem solving behavior in the dog|journal=Anthrozoös|volume=10|issue=4|pages=214–224|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/089279397787000987|doi=10.2752/089279397787000987}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2008a>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2008|title=Wolves outperform dogs in following human social cues|journal=Animal Behaviour|volume=76|pages=1767–1773}}</ref> |

<ref name=udell2008a>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2008|title=Wolves outperform dogs in following human social cues|journal=Animal Behaviour|volume=76|pages=1767–1773}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2008b>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Giglio, R. F., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2008|title=Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) use human gestures but not nonhuman tokens to find hidden food|journal=Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=122|pages=84–93}}</ref> |

<ref name=udell2008b>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Giglio, R. F., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2008|title=Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) use human gestures but not nonhuman tokens to find hidden food|journal=Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=122|issue=1|pages=84–93|pmid=18298285|author1=Udell|first1=M. A.|last2=Giglio|first2=R. F.|last3=Wynne|first3=C. D.|doi=10.1037/0735-7036.122.1.84}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2010>{{Cite journal| author=Udell, M.A.R., Dorey, N.R. and Wynne, C.D.L.|journal=Biological Reviews|volume=85|issue=2|pages=327–345|year=2010|title = What did domestication do to dogs? A new account of dogs' sensitivity to human actions|doi=10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00104.x}}</ref> |

<ref name=udell2010>{{Cite journal| author=Udell, M.A.R., Dorey, N.R. and Wynne, C.D.L.|journal=Biological Reviews|volume=85|issue=2|pages=327–345|year=2010|title = What did domestication do to dogs? A new account of dogs' sensitivity to human actions|doi=10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00104.x|pmid=19961472}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2011>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2011|title=Can your dog read your mind? Understanding the causes of canine perspective taking|journal=Learning & Behavior|volume=39|pages=289–302}}</ref> |

<ref name=udell2011>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2011|title=Can your dog read your mind? Understanding the causes of canine perspective taking|journal=Learning & Behavior|volume=39|pages=289–302}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2012>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Spencer, J. M., Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2012|title=Human-socialized wolves follow diverse human gestures… and they may not be alone|journal=International Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=25|pages=97–117}}</ref> |

<ref name=udell2012>{{cite journal|authors=Udell, M. A. R, Spencer, J. M., Dorey, N. R., & Wynne, C. D. L.|year=2012|title=Human-socialized wolves follow diverse human gestures… and they may not be alone|journal=International Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=25|pages=97–117}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=udell2014>{{cite book|author=Udell, M.A.R. |title=Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior|chapter=10. A Dog’s-Eye View of Canine Cognition|editor=A. Horowitz|publisher=Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg| year=2014| |

<ref name=udell2014>{{cite book|author=Udell, M.A.R. |title=Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior|chapter=10. A Dog’s-Eye View of Canine Cognition|editor=A. Horowitz|publisher=Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg| year=2014| doi= 10.1007/978-3-642-53994-7_10|url=http://www.moniqueudell.com/MoniqueUdell/Publications/Entries/2014/4/2_A_Dogs-Eye_View_of_Canine_Cognition.html}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=vankerkhove2004>van Kerkhove, W., 2004. A fresh look at the wolf-pack theory of companion-animal dog social behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 7, 279-285</ref> |

<ref name=vankerkhove2004>van Kerkhove, W., 2004. A fresh look at the wolf-pack theory of companion-animal dog social behavior. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 7, 279-285</ref> |

||

<ref name=Viegas2014>{{Citation | last = Viegas | first = Jennifer | title = Dogs Not as Close Kin to Wolves as Thought | newspaper = Discovery News | url = http://news.discovery.com/animals/pets/dogs-not-as-close-kin-to-wolves-as-thought-140116.htm | date = January 16, 2014 | accessdate = December 10, 2014}}</ref> |

<ref name=Viegas2014>{{Citation | last = Viegas | first = Jennifer | title = Dogs Not as Close Kin to Wolves as Thought | newspaper = Discovery News | url = http://news.discovery.com/animals/pets/dogs-not-as-close-kin-to-wolves-as-thought-140116.htm | date = January 16, 2014 | accessdate = December 10, 2014}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:40, 7 June 2015

Dog behavior is the internally coordinated responses (actions or inactions) of the domestic dog (individuals or groups) to internal and/or external stimuli.[1] As the oldest domesticated animal species, with estimates ranging from 9,000–30,000 years BCE, the behavior of dogs has inevitably have been shaped by millennia of contact with humans. As a result of this physical and social evolution, dogs, more than any other species, have acquired the ability to understand and communicate with humans and they are uniquely attuned to our behaviors.[2] Behavioral scientists have uncovered a surprising set of social-cognitive abilities in the domestic dog. These abilities are not expressed by the dog's closest canine relatives nor by other mammals such as great apes. Rather, these skills parallel some of the social-cognitive skills of human children.[3]

Evolution/Domestication/Co-evolution with humans

The origin of the domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris or Canis familiaris) is not clear. Nuclear DNA evidence points to a single domestication 11,000-16,000 years ago that predates the rise of agriculture and implies that the earliest dogs arose along with hunter-gatherers and not agriculturists.[4] Mitochondrial DNA evidence points to a domestication 18,800-32,100 years ago and that all modern dogs are most closely related to ancient wolf fossils that have been found in Europe,[5][6] compared to earlier hypotheses which proposed origins in Eurasia as well as Eastern Asia.[7][8][9] The 2 recent genetic analyses indicate that the dog is not a descendant of the extant (i.e. living) gray wolf but forms a sister clade, that the ancestor is an extinct wolf-like canid and the dog's genetic closeness to modern wolves is due to admixture.[4][10]

How dogs became domesticated is not clear, however the two main hypothesis are self-domestication or human domestication.

There exists evidence of human-canine coevolution.

Cognition

Cognition describes the mental capacities of animals. Dogs have frequently been used in studies on cognition, for example, in the learning processes of classical and operant conditioning. As with many animals, the cognitive capacities of dogs are affected by both genetic and environmental factors[11] as expressed in the "nature versus nurture" debate. The great majority of modern research on dog cognition has focused on pet dogs living in human homes in developed countries. This is only a small minority of the domestic dog population and dogs from other populations may show quantifiably different cognitive behavior towards humans.[12] Furthermore, there is a possibility that breed differences can confound studies on cognitive capacity.[13]

Dogs have a general behavioral trait of strongly preferring novelty ("neophillia") compared to familiarity.[14] The average sleep time of a dog in captivity in a 24 hour period is 10.1 hours.[15]

Behavioral scientists have uncovered a surprising set of social-cognitive abilities in the otherwise humble domestic dog. These abilities are not possessed by dogs' closest canine relatives nor by other highly intelligent mammals such as great apes. Rather, these skills parallel some of the social-cognitive skills of human children.[3]

As the oldest domesticated animal species, the cognitive capacities of dogs inevitably have been shaped by millennia of contact with humans.[16][17] As a result of this physical and social evolution, dogs have acquired an ability to understand and communicate with humans.[18] Research in canine cognition is revealing the range and variability of skills such as following pointing and gaze cues,[18][19][20] fast mapping of novel words,[21] cognitive bias[22] and the possibility that dogs have other emotions.[23]

Effects of dominance

In a problem-solving experiment, dominant dogs generally performed better than subordinates, but only when they observed a human demonstrator’s actions. This indicates that social rank affects performance in social learning situations. In social groups with a clear hierarchy, dominant individuals are the more influential demonstrators and the knowledge transfer will, therefore, be unidirectional. If dog-human groups are regarded as hierarchical social units, humans are usually considered as the leaders, meaning the human will be the most influential demonstrator for the dominant dog. Subordinate dogs will learn better from the dominant dog that is adjacent in the hierarchy.[24]

Fast mapping

In humans, "fast mapping" is the ability to form quick and rough hypotheses about the meaning of a new word after only a single exposure. A study with a border collie, Rico, showed he was able to fast map. Rico initially knew the labels of over 200 different items. He inferred the names of novel items by exclusion learning and correctly retrieved those novel items immediately and also 4 weeks after the initial exposure. This retrieval rate is comparable to the performance of 3-year-old humans.[21]

Object permanence

The concept of "object permanence" relates to the ability of an animal to understand that objects continue to exist even when they have moved outside of their field of perception. Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget described the development of object permanence in human infants as having six stages. This stepwise approach is sometimes used in studies of the cognitive abilities of non-human animals. There is ample evidence that dogs reach the advanced stage of 5 in which they are successful at “successive visible displacement” in which the experimenter will move the object behind multiple screens before leaving it behind the last visited location; Stage 5 object permanence is fully developed at 8-weeks-old. There is conflicting evidence whether dogs reach Stage 6 of Piaget’s object permanence development model.[25]

Senses

Vision

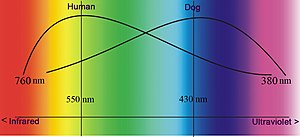

Like most mammals, dogs have only two types of cone photoreceptor, making them dichromats.[11][26][27][28] These cone cells are maximally sensitive between 429 nm and 555 nm. Behavioural studies have shown that the dog's visual world consists of yellows, blues and grays,[28] but they have difficulty differentiating red and green making their color vision equivalent to red–green color blindness in humans (deuteranopia). When a human perceives an object as "red", this object appears as "yellow" to the dog and the human perception of "green" appears as "white", a shade of gray. This white region (the neutral point) occurs around 480 nm, the part of the spectrum which appears blue-green to humans. For dogs, wavelengths longer than the neutral point cannot be distinguished from each other and all appear as yellow.[28]

The dog's visual system has evolved to aid proficient hunting.[11] While a dog's visual acuity is poor (that of a poodle's has been estimated to translate to a Snellen rating of 20/75,[11] their visual discrimination for moving objects is very high; dogs have been shown to be able to discriminate between humans (e.g., identifying their human guardian) at a range of between 800 and 900 metres (2,600 and 3,000 ft), however this range decreases to 500–600 metres (1,600–2,000 ft) if the object is stationary.[11]

Olfaction

While the human brain is dominated by a large visual cortex, the dog brain is dominated by an olfactory cortex. The olfactory bulb in dogs is roughly forty times bigger than the olfactory bulb in humans, relative to total brain size, with 125 to 220 million smell-sensitive receptors. The bloodhound exceeds this standard with nearly 300 million receptors.[11]

Hearing

The frequency range of dog hearing is approximately 40 Hz to 60,000 Hz,[29] which means that dogs can detect sounds far beyond the upper limit of the human auditory spectrum.[27][29][30] In addition, dogs have ear mobility, which allows them to rapidly pinpoint the exact location of a sound.[31] Eighteen or more muscles can tilt, rotate, raise, or lower a dog's ear. The ears are often used in communication of, for example, the dog's mood.[citation needed] A dog can identify a sound's location much faster than a human can, as well as hear sounds at four times the distance.[31]

Magnetic sensitivity

Dogs prefer, when they are off the leash and Earth's magnetic field is calm, to urinate and defecate with their bodies aligned on a north-south axis.[32]

Social behavior

Play

Dog-dog

Play between dogs usually involves several behaviours that are often seen in aggressive encounters, for example, nipping, biting, growling and biting. It is therefore important for the dogs to place these behaviours in the context of play, rather than aggression. Dogs signal their intent to play with a range of behaviours including a "play-bow", "face-paw" "open-mouthed play face" and postures inviting the other dog to chase the initiator. Similar signals are given throughout the play bout to maintain the context of the potentially aggressive activities.[33]

From a young age, dogs engage in play with one another. Dog play is made up primarily of mock fights. It is believed that this behavior, which is most common in puppies, is training for important behaviors later in life. Play between puppies is not necessarily a 50:50 symmetry of dominant and submissive roles between the individuals; dogs who engage in greater rates of dominant behaviours (e.g. chasing, forcing partners down) at later ages also initiate play at higher rates. This could imply that winning during play becomes more important as puppies mature.[34]

Dog-human

The motivation for a dog to play with another dog is distinct from that of a dog playing with a human. Dogs walked together with opportunities to play with one another, play with their owners with the same frequency as dogs being walked alone. Dogs in households with two or more dogs play more often with their owners than dogs in households with a single dog, indicating the motivation to play with other dogs does not substitute for the motivation to play with humans.[35]

It is a common misconception that winning and losing games such as "tug-of-war" and "rough-and-tumble" can can influence a dog's dominance relationship with humans. Rather, the way in which dogs play indicates their temperament and relationship with their owner. Dogs that play rough-and-tumble are more amenable and show lower separation anxiety than dogs which play other types of games, and dogs playing tug-of-war and "fetch" are more confident. Dogs which start the majority of games are less amenable and more likely to be aggressive.[36]

Playing with humans can affect the cortisol levels of dogs. In one study, the cortisol responses of police dogs and border guard dogs was assessed after playing with their handlers. The cortisol concentrations of the police dogs increased, whereas the border guard dogs' hormone levels decreased. The researchers noted that during the play sessions, police officers were disciplining their dogs, whereas the border guards were truly playing with them, i.e. this included bonding and affectionate behaviours. They commented that several studies have shown that behaviours associated with control, authority or aggression increase cortisol, whereas play and affiliative behaviour decrease cortisol levels.[37]

Empathy

In 2012, a study found that dogs oriented toward their owner or a stranger more often when the person was pretending to cry than when they were talking or humming. When the stranger pre-tended to cry, rather than approaching their usual source of comfort, their owner, dogs sniffed, nuzzled and licked the stranger instead. The dogs’ pattern of response was behaviorally consistent with an expression of empathic concern.[38]

Personalities

Several personality traits in dogs are recognised. These include "Playfulness", "Curiosity/Fearlessness, "Chase-proneness", "Sociability and Aggressiveness" and "Shyness–Boldness".[39][40]

Leadership, dominance and social groups

Dominance is a descriptive term for the relationships between pairs of individuals. Among ethologists, dominance has been defined as ‘‘an attribute of the pattern of repeated, agonistic interactions between two individuals, characterized by a consistent outcome in favor of the same dyad member and a default yielding response of its opponent rather than escalation. The status of the consistent winner is dominant and that of the loser subordinate.’’[41] Another definition is that a dominint animal has priority of access to resources.[41] Dominance is a relative attibute, not absolute; there is no reason to assume that a high-ranking individual in one group would also become high ranking if moved to another. Nor is there any good evidence that ‘‘dominance’’ is a lifelong character trait. Competitive behavior characterized by confident (e.g. growl, inhibited bite, stand over, mount, stare at, chase, bark at) and submissive (e.g. crouch, avoid, displacement lick/yawn, run away) patterns exchanged.[42]

One test to ascertain which in a group was the dominant dog used the following criteria: When a stranger comes to the house, which dog starts to bark first or if they start to bark together, which dog barks more or longer? Which dog licks more often the other dog’s mouth? If the dogs get food at the same time and at the same spot, which dog starts to eat first or eats the other dog’s food? If the dogs start to fight, which dog wins usually?[43]

Domestic dogs appear to pay little attention to relative size, despite the large weight differences between the largest and smallest individuals; for example, size was not a predictor of the outcome of encounters between dogs meeting while being exercised by their owners nor was size correlated with neutered male dogs.[44] Therefore, many dogs do not appear to pay much attention to the actual fighting ability of their opponent, presumably allowing differences in motivation (how much the dog values the resource) and perceived motivation (what the behavior of the other dog signifies about the likelihood that it will escalate) to play a much greater role.[42]

Two dogs that are contesting possession of a highly valued resource for the first time, if one is in a state of emotional arousal, or if one is in pain, or if reactivity is influenced by recent endocrine changes or motivational states such as hunger, then the outcome of the interaction may be different than if none of these factors were present. Equally, the threshold at which aggression is shown may be influenced by a range of medical factors, or, in some cases, precipitated entirely by pathological disorders. Hence, the contextual and physiological factors present when 2 dogs first encounter each other may profoundly influence the long-term nature of the relationship between those dogs. The complexity of the factors involved in this type of learning means that dogs may develop different ‘‘expectations’’ about the likely response of another individual for each resource in a range of different situations. Puppies learn early not to challenge an older dog and this respect stays with them into adulthood. When adult animals meet for the first time, they have no expectations of the behavior of the other: they will both, therefore, be initially anxious and vigilant in this encounter (characterized by the tense body posture and sudden movements typically seen when 2 dogs first meet), until they start to be able to predict the responses of the other individual. The outcome of these early adult–adult interactions will be influenced by the specific factors present at the time of the initial encounters. As well as contextual and physiological factors, the previous experiences of each member of the dyad of other dogs will also influence their behavior.[42]

Feral dogs

Feral dogs are those dogs living in a wild state with no food and shelter intentionally provided by humans, and showing a continuous and strong avoidance of direct human contacts.[45] In the developing world pet dogs are uncommon, but feral, village or community dogs are plentiful around humans.[46] The distinction between feral, stray, and free ranging dogs is sometimes a matter of degree, and a dog may shift its status throughout its life. In some unlikely but observed cases, a feral dog that was not born wild but living with a feral group can become rehabilitated to a domestic dog with an owner. A dog can become a stray when it escapes human control, by abandonment or being born to a stray mother. A stray dog can become feral when forced out of the human environment or when co-opted or socially accepted by a nearby feral group. Feralization occurs through the development of a fear response to humans.[45]

Feral dogs are not reproductively self-sustaining, suffer from high rates of juvenile mortality, and depend indirectly on humans for their food, their space, and the supply of co-optable individuals.[45]

See further: behavior compared to other canids.

Reproduction behavior

Estrous cycle and mating

Although puppies do not have the urge to procreate, males sometimes engage in sexual play in the form of mounting, as early as 5 weeks-of-age.

Dogs reach sexual maturity and can reproduce during their first year, in contrast to wolves at two years-of-age. Bitches have their first estrus ("heat") at 6 to 12 months-of-age; smaller dogs tend to come into heat earlier whereas larger dogs take longer to mature.

Dog bitches have an estrous cycle that is nonseasonal and monestrus, i.e. there is only one estrus per estrous cycle. The interval between one estrus and another is, on average, seven months, however, this may range between 4 to 12 months. This interestrous period is not influenced by the photoperiod or pregnancy.[47]

For several days before estrus, a phase called proestrus, the bitch may show greater interest in male dogs and "flirt" with them (proceptive behavior). There is progressive vulval swelling and some bleeding. If males try to mount a bitch during proestrus, she may avoid mating by sitting down or turning round and growling or snapping.

Estrous behavior in the bitch is usually indicated by her standing still with the tail held up, or to the side of the perineum, when the male sniffs the vulva and attempts to mount. This tail position is sometimes called “flagging”. The bitch may also turn, presenting the vulva to the male, The average duration od estrus is 9 days with spontaneous ovulation usually about 3 days after the onset of estrus.[47]

The male dog mounts the female and because he has a bone in his penis (the Os penis), he is able to acieve intromission with a non-erect penis. The penis enlarges inside the vagina, thereby preventing its withdrawal; this is sometimes known as the “tie” or “copulatory lock”. The male dog rapidly thrust into the female for 1–2 minutes then dismounts with the erect penis still inside the vagina, and turns to stand rear-end to rear-end with the bitch for up to 30 to 40 minutes; the penis is twisted 180 degrees in a lateral plane. During this time, prostatic fluid is ejaculated.[47]

The bitch can bear another litter within 8 months of the previous one. Dogs are polygamous in contrast to wolves that are generally monogamous. Therefore dogs have no pair bonding and the protection of a single mate, but rather have multiple mates in a year. The consequence is that wolves put a lot of energy into producing a few pups in contrast to dogs that maximize the production of pups. This higher pup production rate enables dogs to maintain or even increase their population with a lower pup survival rate than wolves, and allows dogs a greater capacity than wolves to grow their population after a population crash or when entering a new habitat. It is proposed that these differences are an alternative breeding strategy, one adapted to a life of scavenging instead of hunting.[48]

Parenting and early life

All of the wild members of the genus Canis display complex coordinated parental behaviors. Wolf pups are cared primarily by their mother for the first 3 months of their life when she remains in the den with them while they rely on her milk for sustenance and her presence for protection. The father brings her food. Once they leave the den and can chew, the parents and pups from previous years regurgitate food for them. Wolf pups become independent by 5 to 8 months, although they often stay with their parents for years. In contrast, dog pups are cared for by the mother and rely on her for milk and protection but she gets no help from the father nor other dogs. Once pups are weaned around 10 weeks they are independent and receive no further maternal care.[48]

Behavior problems

A survey of 203 dog owners in Melbourne, Australia, found that the main behaviour problems reported by owners were overexcitement (63%) and jumping up on people (56%).[49]

Separation anxiety

When dogs are separated from humans, usually the owner, they often display behaviours such as destructiveness, faecal or urinary elimination, hypersalivation or vocalisation. Dogs from single-owner homes are approximately 2.5 times more likely to have separation anxiety compared to dogs from multiple-owner homes. Furthermore, sexually intact dogs are only one third as likely to have separation anxiety as neutered dogs. The sex of dogs and whether there is another pet in the home do not have an affect on separation anxiety.[50]

Tail chasing

Tail chasing can be classified as a stereotypy. In one clinical study on the behaval problem, 18 tail-chasing terriers were given clomipramine orally at a dosage of 1 to 2 mg/kg (0.5 to 0.9 mg/lb) of body weight, every 12 hours. Three of the dogs required treatment at a slightly higher dosage range to control tail chasing, however, after 1 to 12 weeks of treatment, 9 of 12 dogs were reported to have a 75% or greater reduction in tail chasing.[51]

Behavior compared to other canids

Comparisons made within the wolf-like canids allows the identification of those behaviors that may have been inherited from common ancestry and those that may have been the result of domestication or other relatively recent environmental changes.[45]

Social structure

Among canids, packs are the social units that hunt, rear young and protect a communal territory as a stable group and their members are usually related.[52] Members of the feral dog group are usually not related. Feral dog groups are composed of a stable 2-6 members compared to the 2-15 member wolf pack whose size fluctuates with the availability of prey and reaches a maximum in winter time. The feral dog group consists of monogamous breeding pairs compared to the one breeding pair of the wolf pack. Agonistic behavior does not extend to the individual level and does not support a higher social structure compared to the ritualized agonistic behavior of the wolf pack that upholds its social structure. Feral pups have a very high mortality rate that adds little to the group size, with studies showing that adults are usually killed through accidents with humans, therefore other dogs need to be co-opted from villages to maintain stable group size.[45]

Socialization

The critical period for socialization begins with to walk and explore the environment. Dog and wolf pups both develop the ability to see, hear and smell at 4 weeks of age. Dogs begin to explore the world around them at 4 weeks of age with these senses available to them, while wolves begin to explore at 2 weeks of age when they have the sense of smell but are functionally blind and deaf. The consequences of this is that more things are novel and frightening to wolf pups. The critical period for socialization closes with the avoidance of novelty, when the animal runs away from - rather than approaching and exploring - novel objects. For dogs this develops between 4–8 weeks of age. Wolves reach the end of the critical period after 6 weeks, after which it is not possible to socialize a wolf.[48]

Dog puppies require as little as 90 minutes of contact with humans during their critical period of socialization to form a social attachment. This will not create a highly social pet but a dog that will solicit human attention.[53] Wolves require 24 hours contact a day starting before 3 weeks of age. To create a socialized wolf the pups are removed from the den at 10 days of age, kept in constant human contact until they are 4 weeks old when they begin to bite their sleeping human companions, then spend only their waking hours in the presence of humans. This socialization process continues until age 4 months, when the pups can join other captive wolves but will require daily human contact to remain socialized. Despite this intensive socialization process, a well-socialized wolf will behave differently to a well-socialized dog and will display species-typical hunting and reproductive behaviors, only closer to humans than a wild wolf. These wolves do not generalize their socialization to all humans in the same manner as a socialized dog and they remain more fearful of novelty compared to socialized dogs.[54]

In 1982, a study to observe the differences between dogs and wolves raised in similar conditions took place. The dog puppies preferred larger amounts of sleep at the beginning of their lives, while the wolf puppies were much more active. The dog puppies also preferred the company of humans, rather than their canine foster mother, though the wolf puppies were the exact opposite, spending more time with their foster mother. The dogs also showed a greater interest in the food given to them and paid little attention to their surroundings, while the wolf puppies found their surroundings to be much more intriguing than their food or food bowl. The wolf puppies were observed taking part in antagonistic play at a younger age, while the dog puppies did not display dominant/submissive roles until they were much older. The wolf puppies were rarely seen as being aggressive to each other or towards the other canines. On the other hand, the dog puppies were much more aggressive to each other and other canines, often seen full-on attacking their foster mother or one another.[55]

Cognition

Despite claims that dogs show more human-like social cognition than wolves,[18][19][56] several recent studies have demonstrated that if wolves are properly socialized to humans and have the opportunity to interact with humans regularly, then they too can succeed on some human-guided cognitive tasks,[57][58][59][60][61] in some cases out-performing dogs at an individual level.[62] Similar to dogs, wolves can also follow more complex point types made with body parts other than the human arm and hand (e.g. elbow, knee, foot).[61] Both dogs and wolves have the cognitive capacity for prosocial behavior toward humans, however it is not guaranteed. For canids to perform well on traditional human-guided tasks (e.g. following the human point) both relevant lifetime experiences with humans - including socialization to humans during the critical period for social development - and opportunities to associate human body parts with certain outcomes (such as food being provided by human hands, a human throwing or kicking a ball, etc.) are required.[63]

After undergoing training to solve a simple manipulation task, dogs that are faced with an insoluble version of the same problem look at the human, while socialized wolves do not.[56]

Reproduction

Dogs reach sexual maturity and can reproduce during their first year in contrast to a wolf at two years. The dog female can bear another litter within 8 months of the last one. The canid genus is influenced by the photoperiod and reproduce generally in the springtime.[45] Domestic dogs are not reliant on seasonality for reproduction in contrast to a the wolf, coyote, Australian dingo and African basenji that may have only one, seasonal, estrus each year.[47] Feral dogs are influenced by the photoperiod with around half of the breeding females mating in the springtime, which is thought to indicate an ancestral reproductive trait not overcome by domestication,[45] as can be inferred from wolves[64] and Cape hunting dogs.[65]

Domestic dogs are polygamous in contrast to wolves that are generally monogamous. Therefore domestic dogs have no pair bonding and the protection of a single mate, but rather have multiple mates in a year. There is no paternal care in dogs as opposed to wolves where all pack members assist the mother with the pups. The consequence is that wolves put a lot of energy into producing a few pups in contrast to dogs that maximize the production of pups. This higher pup production rate enables dogs to maintain or even increase their population with a lower pup survival rate than wolves, and allows dogs a greater capacity than wolves to grow their population after a population crash or when entering a new habitat. It is proposed that these differences are an alternative breeding strategy adapted to a life of scavenging instead of hunting.[48] In contrast to domestic dogs, feral dogs are monogamous. Domestic dogs tend to have a litter size of 10, wolves 3, and feral dogs 5-8. Feral pups have a very high mortality rate with only 5% surviving at the age of one year, and sometimes the pups are left unattended making them vulnerable to predators.[45] Domestic dogs stand alone among all canids for a total lack of paternal care.[66]

Dogs differ from wolves and most other large canid species as they generally do not regurgitate food for their young, nor the young of other dogs in the same territory.[67] However, this difference was not observed in all domestic dogs. Regurgitating of food by the females for the young, as well as care for the young by the males, has been observed in domestic dogs, dingos and in feral or semi-feral dogs. In one study or a group of free-ranging dogs, for the first 2 weeks immediately after parturition the lactating females were observed to be more aggressive to protect the pups. The male parents were in contact with the litters as ‘guard’ dogs for the first 6–8 weeks of the litters’ life. In absence of the mothers, they were observed to prevent the approach of strangers by vocalizations or even by physical attacks. Moreover, one male fed the litter by regurgitation showing the existence of paternal care in some free-roaming dogs[68]

Space

Space used by feral dogs is not dissimilar from most other canids in that they use defined traditional areas (home ranges) that tend to be defended against intruders, and have core areas where most of their activities are undertaken. Urban domestic dogs have a home range of 2-61 hectares in contrast to a feral dogs home range of 58 square kilometers. Wolf home ranges vary from 78 square kilometers where prey is deer to 2.5 square kilometers at higher latitudes where prey is moose and caribou. Wolves will defend their territory based on prey abundance and pack density, however feral dogs will defend their home ranges all year. Where wolf ranges and feral dog ranges overlap, the feral dogs will site their core areas closer to human settlement.[45]

Predation

Despite claims in the popular press, studies could not find evidence of a single predation on cattle by feral dogs.[45][69][70] However, domestic dogs were responsible for the death of 3 calves over one 5-year study.[70] Other studies in Europe and North America indicate only limited success in the consumption of wild boar, deer and other ungulates, however it could not be determined if this was predation or scavenging on carcasses. Studies have observed feral dogs conducting brief, uncoordinated chases of small game with constant barking - a technique without success.[45]

In 2004, a study reviewed 5 other studies of feral dogs published between 1975 and 1995 and concluded that their pack structure is very loose and rarely involves any cooperative behavior, either in raising young or in obtaining food.[71] Feral dogs are primarily scavengers, with studies showing that unlike their wild cousins, they are poor ungulate hunters, having little impact on wildlife populations where they are sympatric.[72]: 267 However, several garbage dumps located within the feral dog's home range are important for their survival.[73]

Dogs in human society

Studies using an operant framework have indicated that humans can influence the behavior of dogs through food, petting and voice. Food and 20–30 seconds of petting maintained operant responding in dogs.[74] Some dogs will show a preference for petting once food is readily available, and dogs will remain in close proximity to a person providing petting and show no satiation to that stimulus.[75] Petting alone was sufficient to maintain the operant response of military dogs to voice commands, and responses to basic obedience commands in all dogs increased when only vocal praise was provided for correct responses.[76]

A study using dogs that were trained to remain motionless while unsedated and unrestrained in an MRI scanner exhibited caudate activation to a hand signal associated with reward.[2] Further work found that the magnitude of the canine caudate response is similar to that of humans, while the between-subject variability in dogs may be less than humans.[77] In a further study, 5 scents were presented (self, familiar human, strange human, familiar dog, strange dog). While the olfactory bulb/peduncle was activated to a similar degree by all the scents, the caudate was activated maximally to the familiar human. Importantly, the scent of the familiar human was not the handler, meaning that the caudate response differentiated the scent in the absence of the person being present. The caudate activation suggested that not only did the dogs discriminate that scent from the others, they had a positive association with it. Although these signals came from two different people, the humans lived in the same household as the dog and therefore represented the dog's primary social circle. And while dogs should be highly tuned to the smell of items that are not comparable, it seems that the “reward response” is reserved for their humans.[78]

Research has shown that there are individual differences in the interactions between dogs and their human masters that have significant effects on dog behavior. In 1997, a study showed that the type of relationship between dog and master, characterized as either companionship or working relationship, significantly affected the dog's performance on a cognitive problem-solving task. They speculate that companion dogs have a more dependent relationship with their owners, and look to them to solve problems. In contrast, working dogs are more independent.[79]

Dogs in the family

Dogs at work

Service dogs are those that are trained to help people with disabilities. Detection dogs are trained to using their sense of smell to detect substances such as explosives, illegal drugs, wildlife scat, or blood. In science, dogs have helped humans understand about the conditioned reflex. Attack dogs, dogs that have been trained to attack on command, are employed in security, police, and military roles.

Attacks

In the UK between 2005 and 2013, there were 17 fatal dog attacks. In 2007-08 there were 4,611 hospital admissions due to dog attacks, which increased to 5,221 in 2008-09. It has been estimated that more than 200,000 people a year are bitten by dogs in England, with the annual cost to the National Health Service of treating injuries about £3 million.[80] A report published in 2014 stated there were 6,743 hospital admissions specifically caused by dog bites, a 5.8% increase from the 6,372 admissions in the previous 12 months.[81]

In the US between 1979 and 1996, there were more than 300 human dog bite-related fatalities.[82] In the US in 2013, there were 31 dog-bite related deaths. Each year, more than 4.5 million people in the US are bitten by dogs and almost 1 in 5 require medical attention.[83]

Attack training is condemned by some as promoting ferocity in dogs; a 1975 American study showed that 10% of dogs that have bitten a person received attack dog training at some point.[84]

See also

- Alpha roll

- Dog communication

- Dog intelligence

- Pack (canine)

- Pack hunter

- Separation anxiety disorder (humans)

References

- ^ Levitis, Daniel; William Z. Lidicker, Jr, Glenn Freund; Freund, Glenn (June 2009). "Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 78: 103–10. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038027, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0038027instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1179670, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1179670instead. - ^ a b Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, Marco; Fan, Zhenxin; Marx, Peter; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Beale, Holly; Ramirez, Oscar; Hormozdiari, Farhad; Alkan, Can; Vilà, Carles; Squire, Kevin; Geffen, Eli; Kusak, Josip; Boyko, Adam R.; Parker, Heidi G.; Lee, Clarence; Tadigotla, Vasisht; Siepel, Adam; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Harkins, Timothy T.; Nelson, Stanley F.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; Novembre, John (16 January 2014). "Genome Sequencing Highlights Genes Under Selection and the Dynamic Early History of Dogs". PLOS Genetics. 10 (1). PLOS Org: e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170. PMID 24453982. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Sawyer, S.K.; Greenfield, D.L.; Germonpré, M.B.; Sablin, M.V.; López-Giráldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H-P.; Loponte, D.M.; Acosta, A.A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R.W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J.E.; Druzhkova, A.S.; Graphodatsky, A.S.; Ovodov, N.D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A.H.; Schweizer, R.M.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Leonard, J.A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Pääbo, S.; et al. (15 November 2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160). AAAS: 871–874. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Wolpert, Stuart (November 14, 2013), "Dogs likely originated in Europe more than 18,000 years ago, UCLA biologists report", UCLA News Room, retrieved December 10, 2014

- ^ Wang, Xiaoming. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia University Press. pp. 233–236.

- ^ Miklósi, Ãdám. Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford. p. 167.

- ^ Cossins, Dan (May 16, 2013), "Dogs and Human Evolving Together", The Scientist, retrieved January 12, 2014

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (January 16, 2014), "Dogs Not as Close Kin to Wolves as Thought", Discovery News, retrieved December 10, 2014

- ^ a b c d e f Coren, Stanley (2004). How Dogs Think. First Free Press, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2232-6.[page needed]

- ^ Udell, M.A.R., Dorey, N.R. and Wynne, C.D.L. (2010). "What did domestication do to dogs? A new account of dogs' sensitivity to human actions". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 327–345. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00104.x. PMID 19961472.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Head, E., Mehta, R., Hartley, J., Kameka, M., Cummings, B.J., Cotman, C.W., Ruehl, W.W. and Milgram, N.W. (1995). "Spatial learning and memory as a function of age in the dog". Behavioral Neuroscience. 109 (5): 851–858. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.109.5.851. PMID 8554710.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaulfuß, P. and Mills, D.S. (2008). "Neophilia in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and its implication for studies of dog cognition". Animal Cognition. 11 (3): 553–556. doi:10.1007/s10071-007-0128-x. PMID 18183436.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "40 Winks?" Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic Vol. 220, No. 1. July 2011.

- ^ Shipman P (2011) The Animal Connection. A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human. New York: W.W. Norton and Co

- ^ Bradshaw J (2011) Dog Sense. How the New Science of Dog Behavior Can Make You a Better Friend. New York: Basic Books

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1072702, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1072702instead. - ^ a b Hare B, Tomasello M (2005) Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends Cogn Sci 9: 439–444

- ^ Teglas E, Gergely A, Kupan K, Miklosi A, Topal J (2012) Dogs' gaze following is tuned to human communicative signals. Current Biology 22: 209–212

- ^ a b Kaminski, J., Call, J. and Fischer, J. (2004). "Word learning in a domestic dog: Evidence for "fast mapping"". Science. 304 (5677): 1682–1683. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1682K. doi:10.1126/science.1097859. PMID 15192233.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mendl, M., Brooks, J., Basse, C., Burman, O., Paul, E., Blackwell, E. and Casey, R. (2010). "Dogs showing separation-related behaviour exhibit a 'pessimistic' cognitive bias" (PDF). Current Biology. 20 (19).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bekoff M (2007) The Emotional Lives of Animals. Novato: New World Publishers

- ^ Péter Pongrácz, Petra Bánhegyi and Ádám Miklósi (2012) When rank counts—dominant dogs learn better from a human demonstrator in a two-action test — Behaviour 149 (2012) 111–132