Dicynodontia: Difference between revisions

m fix refs |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

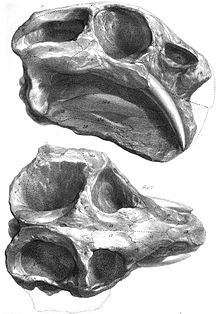

[[Image:Dicynodon lacerticeps.jpg|thumb|right|An illustration of the skull of ''[[Dicynodon lacerticeps]]'', first published in an 1845 description by [[Richard Owen]].]] |

[[Image:Dicynodon lacerticeps.jpg|thumb|right|An illustration of the skull of ''[[Dicynodon lacerticeps]]'', first published in an 1845 description by [[Richard Owen]].]] |

||

Dicynodonts have been known since the mid-1800s. South African geologist [[Andrew Geddes Bain]] gave the first description of dicynodonts in 1845. At the time, Bain was a supervisor for the construction of military roads under the [[Corps of Royal Engineers]] and had found many reptilian fossils during his surveys of South Africa. Bain described these fossils in an 1845 letter published in ''[[Geological Society of London|Transactions of the Geological Society of London]]'', calling them "bidentals" for their two prominent tusks.<ref name=BAG45>{{cite journal |last=Bain |first=A.G. |year=1845 |title=On the discovery of fossil remains of bidental and other reptiles in South Africa |journal=Transactions of the |

Dicynodonts have been known since the mid-1800s. South African geologist [[Andrew Geddes Bain]] gave the first description of dicynodonts in 1845. At the time, Bain was a supervisor for the construction of military roads under the [[Corps of Royal Engineers]] and had found many reptilian fossils during his surveys of South Africa. Bain described these fossils in an 1845 letter published in ''[[Geological Society of London|Transactions of the Geological Society of London]]'', calling them "bidentals" for their two prominent tusks.<ref name=BAG45>{{cite journal |last=Bain |first=A.G. |year=1845 |title=On the discovery of fossil remains of bidental and other reptiles in South Africa |journal=Transactions of the Geological Society of London |volume=1 |pages=53–59 |doi=10.1144/GSL.JGS.1845.001.01.72}}</ref> In that same year, English paleontologist [[Richard Owen]] named two species of dicynodonts from South Africa: ''[[Dicynodon lacerticeps]]'' and ''[[Dicynodon bainii]]''. Since Bain was preoccupied with the Corps of Royal Engineers, he wanted Owen to describe his fossils more extensively. Owen did not publish a description until 1876 in his ''Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum''.<ref name=OR76>{{cite book |last=Owen |first=R. |year=1876 |title=Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum |publisher=British Museum |location=London |pages=88}}</ref> By this time, many more dicynodonts had been described. In 1859, another important species called ''[[Ptychognathus declivis]]'' was named from South Africa. A year later, in 1860, Owen named the group Dicynodontia.<ref name=OR60>{{cite journal |last=Owen |first=R. |year=1860 |title=On the orders of fossil and recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time |journal=Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science |volume=1859 |pages=153–166}}</ref> In his ''Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue'', Owen honored Bain by erecting [[Bidentalia]] as a replacement name for his Dicynodontia.<ref name=OR76/> The name Bidentalia quickly fell out of use in the following years, replaced by popularity of Owen's Dicynodontia.<ref name=KA09>{{cite journal |last=Kammerer |first=C.F. |author2=Angielczyk, K.D. |year=2009 |title=A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids |journal=Zootaxa |volume=2018 |pages=1–24 |url=http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2009/f/z02018p024f.pdf}}</ref> |

||

Geological Society of London |pages=53–59}}</ref> In that same year, English paleontologist [[Richard Owen]] named two species of dicynodonts from South Africa: ''[[Dicynodon lacerticeps]]'' and ''[[Dicynodon bainii]]''. Since Bain was preoccupied with the Corps of Royal Engineers, he wanted Owen to describe his fossils more extensively. Owen did not publish a description until 1876 in his ''Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum''.<ref name=OR76>{{cite book |last=Owen |first=R. |year=1876 |title=Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum |publisher=British Museum |location=London |pages=88}}</ref> By this time, many more dicynodonts had been described. In 1859, another important species called ''[[Ptychognathus declivis]]'' was named from South Africa. A year later, in 1860, Owen named the group Dicynodontia.<ref name=OR60>{{cite journal |last=Owen |first=R. |year=1860 |title=On the orders of fossil and recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time |journal=Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science |volume=1859 |pages=153–166}}</ref> In his ''Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue'', Owen honored Bain by erecting [[Bidentalia]] as a replacement name for his Dicynodontia.<ref name=OR76/> The name Bidentalia quickly fell out of use in the following years, replaced by popularity of Owen's Dicynodontia.<ref name=KA09>{{cite journal |last=Kammerer |first=C.F. |author2=Angielczyk, K.D. |year=2009 |title=A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids |journal=Zootaxa |volume=2018 |pages=1–24 |url=http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2009/f/z02018p024f.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

==Evolutionary history== |

==Evolutionary history== |

||

| Line 34: | Line 33: | ||

Only four lineages are known to survived the [[Permian–Triassic extinction event|end Permian extinction]]; the first three represented with a single genus each; [[Myosaurus]], [[Kombuisia]] and [[Lystrosaurus]], the latter being the most common and widespread herbivores of the [[Induan]] (earliest [[Triassic]]). None of these survived long into the Triassic. The fourth group was the [[Kannemeyeriiformes]], the only dicynodonts who diversified during the Triassic.<ref>[http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0064203 On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America]</ref> These stocky, pig- to ox-sized animals were the most abundant herbivores worldwide from the [[Olenekian]] to the [[Ladinian]] age. By the [[Carnian]] they had been supplanted by [[Traversodontidae|traversodont]] cynodonts and [[rhynchosaur]] reptiles. During the [[Norian]] (middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivore was taken over by [[sauropodomorph]] dinosaurs. |

Only four lineages are known to survived the [[Permian–Triassic extinction event|end Permian extinction]]; the first three represented with a single genus each; [[Myosaurus]], [[Kombuisia]] and [[Lystrosaurus]], the latter being the most common and widespread herbivores of the [[Induan]] (earliest [[Triassic]]). None of these survived long into the Triassic. The fourth group was the [[Kannemeyeriiformes]], the only dicynodonts who diversified during the Triassic.<ref>[http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0064203 On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America]</ref> These stocky, pig- to ox-sized animals were the most abundant herbivores worldwide from the [[Olenekian]] to the [[Ladinian]] age. By the [[Carnian]] they had been supplanted by [[Traversodontidae|traversodont]] cynodonts and [[rhynchosaur]] reptiles. During the [[Norian]] (middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivore was taken over by [[sauropodomorph]] dinosaurs. |

||

Fossils discovered in [[Poland]] indicate that dicynodonts survived at least until the early [[Rhaetian]] (latest Triassic).<ref name=DSN08>{{cite journal |author=Jerzy Dzik, Tomasz Sulej, and Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki |year=2008 |title=A dicynodont−theropod association in the latest Triassic of Poland |url=http://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app53-733.html |journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica |volume=53 |issue=4 |pages=733–738 |doi=10.4202/app.2008.0415}}</ref> Six fragments of fossil bone interpreted as remains of a skull discovered in Australia ([[Queensland]]) might indicate that dicynodonts survived into the [[Cretaceous]] in southern [[Gondwana]].<ref name = "Thulborn"> |

Fossils discovered in [[Poland]] indicate that dicynodonts survived at least until the early [[Rhaetian]] (latest Triassic).<ref name=DSN08>{{cite journal |author=Jerzy Dzik, Tomasz Sulej, and Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki |year=2008 |title=A dicynodont−theropod association in the latest Triassic of Poland |url=http://www.app.pan.pl/article/item/app53-733.html |journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica |volume=53 |issue=4 |pages=733–738 |doi=10.4202/app.2008.0415}}</ref> Six fragments of fossil bone interpreted as remains of a skull discovered in Australia ([[Queensland]]) might indicate that dicynodonts survived into the [[Cretaceous]] in southern [[Gondwana]].<ref name = "Thulborn">{{cite journal|last1=Thulborn|first1=T.|last2=Turner|first2=S.|title=The last dicynodont: an Australian Cretaceous relict|journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|volume=270|issue=1518|year=2003|pages=985–993|doi=10.1098/rspb.2002.2296 |jstor=3558635}}</ref> However, Agnolin ''et al.'' (2010) considered the affinities of the specimen from Australia to be uncertain, and noted its similarity to the skull bones of some [[Baurusuchidae|baurusuchian]] crocodyliforms, such as ''[[Baurusuchus|Baurusuchus pachecoi]]''.<ref name=agnolinetal2010>{{cite journal |last=Agnolin |first=F. L. |author2=Ezcurra, M. D. |author3=Pais, D. F. |author4= Salisbury, S. W. |year=2010 |title=A reappraisal of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaur faunas from Australia and New Zealand: Evidence for their Gondwanan affinities |journal=Journal of Systematic Palaeontology |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=257–300 |doi=10.1080/14772011003594870}}</ref> |

||

With the decline and extinction of the kannemeyerids, there were to be no more dominant large synapsid herbivores until the middle [[Paleocene]] epoch (60 Ma) when [[mammal]]s, descendants of [[cynodont]]s, began to diversify after the extinction of the dinosaurs. |

With the decline and extinction of the kannemeyerids, there were to be no more dominant large synapsid herbivores until the middle [[Paleocene]] epoch (60 Ma) when [[mammal]]s, descendants of [[cynodont]]s, began to diversify after the extinction of the dinosaurs. |

||

| Line 40: | Line 39: | ||

==Systematics== |

==Systematics== |

||

===Taxonomy=== |

===Taxonomy=== |

||

Dicynodontia was originally named by English paleontologist [[Richard Owen]]. It was erected as a family of the order Anomodontia and included the genera ''[[Dicynodon]]'' and ''[[Ptychognathus]]''. Other families of Anomodontia included [[Gnathodontia]], which included ''[[Rhynchosaurus]]'' (now known to be an [[archosauromorph]]) and [[Cryptodontia]], which included ''[[Oudenodon]]''. Cryptodonts were distinguished from dicynodonts from their absence of tusks. Although it lacks tusks, ''Oudenodon'' is now classified as a dicynodont, and the name Cryptodontia is no longer used. [[Thomas Henry Huxley]] revised Owen's Dicynodontia as an order that included ''Dicynodon'' and ''Oudenodon''.<ref name=OHF04>{{cite journal |last=Osborn |first=H.F. |year=1904 |title=Reclassification of the Reptilia |journal=The American Naturalist |volume=38 |issue=446 |pages=93–115 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EHMWAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false |doi=10.1086/278383}}</ref> Dicynodontia was later ranked as a suborder or infraorder with the larger group Anomodontia, which is classified as an order. The ranking of Dicynodontia has varied in recent studies, with Ivakhnenko (2008) considering it a suborder, Ivanchnenko (2008) considering it an infraorder, and Kurkin (2010) considering it an order.<ref name=KAA10>{{cite journal |last=Kurkin |first=A.A. |year=2010 |title=Late Permian dicynodonts of Eastern Europe |journal=Paleontological Journal |volume=44 |issue=6 |pages=72–80}}</ref> |

Dicynodontia was originally named by English paleontologist [[Richard Owen]]. It was erected as a family of the order Anomodontia and included the genera ''[[Dicynodon]]'' and ''[[Ptychognathus]]''. Other families of Anomodontia included [[Gnathodontia]], which included ''[[Rhynchosaurus]]'' (now known to be an [[archosauromorph]]) and [[Cryptodontia]], which included ''[[Oudenodon]]''. Cryptodonts were distinguished from dicynodonts from their absence of tusks. Although it lacks tusks, ''Oudenodon'' is now classified as a dicynodont, and the name Cryptodontia is no longer used. [[Thomas Henry Huxley]] revised Owen's Dicynodontia as an order that included ''Dicynodon'' and ''Oudenodon''.<ref name=OHF04>{{cite journal |last=Osborn |first=H.F. |year=1904 |title=Reclassification of the Reptilia |journal=The American Naturalist |volume=38 |issue=446 |pages=93–115 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=EHMWAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false |doi=10.1086/278383}}</ref> Dicynodontia was later ranked as a suborder or infraorder with the larger group Anomodontia, which is classified as an order. The ranking of Dicynodontia has varied in recent studies, with Ivakhnenko (2008) considering it a suborder, Ivanchnenko (2008) considering it an infraorder, and Kurkin (2010) considering it an order.<ref name=KAA10>{{cite journal |last=Kurkin |first=A.A. |year=2010 |title=Late Permian dicynodonts of Eastern Europe |journal=Paleontological Journal |volume=44 |issue=6 |pages=72–80 |doi=10.1134/S0031030110060092}}</ref> |

||

Many higher taxa, including infraorders and families, have been erected as a means of classifying the large number of dicynodont species. Cluver and King (1983) recognized several main groups within Dicynodontia, including Diictodontia, Endothiodontia, Eodicynodontia, Kingoriamorpha, Pristerodontia, and [[Venyukoviamorpha]].<ref name=CK83>{{cite journal |last=Cluver |first=M.A. |author2=King, G.M. |year=1983 |title=A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodont |journal=Annals of the South African Museum |volume=91 |pages=195–273}}</ref> Many families have been proposed, including [[Cistecephalidae]], [[Diictodontidae]], [[Dicynodontidae]], [[Emydopidae]], [[Endothiodontidae]], [[Kannemeyeriidae]], [[Kingoriidae]], [[Lystrosauridae]], [[Myosauridae]], [[Oudenodontidae]], [[Pristerodontidae]], and [[Robertiidae]]. However, with the rise of [[phylogenetic]]s, most of these taxa are no longer considered valid. Kammerer and Angielczyk (2009) suggested that the problematic taxonomy and nomenclature of Dicynodontia and other groups results from the large number of conflicting studies and the tendency for invalid names to be mistakenly established.<ref name=KA09/> |

Many higher taxa, including infraorders and families, have been erected as a means of classifying the large number of dicynodont species. Cluver and King (1983) recognized several main groups within Dicynodontia, including Diictodontia, Endothiodontia, Eodicynodontia, Kingoriamorpha, Pristerodontia, and [[Venyukoviamorpha]].<ref name=CK83>{{cite journal |last=Cluver |first=M.A. |author2=King, G.M. |year=1983 |title=A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodont |journal=Annals of the South African Museum |volume=91 |pages=195–273}}</ref> Many families have been proposed, including [[Cistecephalidae]], [[Diictodontidae]], [[Dicynodontidae]], [[Emydopidae]], [[Endothiodontidae]], [[Kannemeyeriidae]], [[Kingoriidae]], [[Lystrosauridae]], [[Myosauridae]], [[Oudenodontidae]], [[Pristerodontidae]], and [[Robertiidae]]. However, with the rise of [[phylogenetic]]s, most of these taxa are no longer considered valid. Kammerer and Angielczyk (2009) suggested that the problematic taxonomy and nomenclature of Dicynodontia and other groups results from the large number of conflicting studies and the tendency for invalid names to be mistakenly established.<ref name=KA09/> |

||

| Line 184: | Line 183: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|2}} |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 13:05, 26 December 2015

| Dicynodonts Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull of the dicynodont Endothiodon angusticeps in the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Chainosauria |

| Clade: | †Dicynodontia Owen, 1859 |

| Clades & Genera | |

|

see "Taxonomy" | |

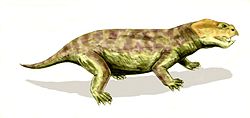

Dicynodontia is a taxon of anomodont therapsids or synapsids with beginnings in the mid-Permian, which were dominant in the Late Permian and continued throughout the Triassic, with a few possibly surviving into the Early Cretaceous. Dicynodonts were herbivorous animals with two tusks, hence their name, which means 'two dog tooth'. They are also the most successful and diverse of the non-mammalian therapsids, with over 70 genera known, varying from rat- to ox-sized.

Characteristics

The dicynodont skull is highly specialised, light but strong, with the synapsid temporal openings at the rear of the skull greatly enlarged to accommodate larger jaw muscles. The front of the skull and the lower jaw are generally narrow and, in all but a number of primitive forms, toothless. Instead, the front of the mouth is equipped with a horny beak, as in turtles and ceratopsian dinosaurs. Food was processed through retraction of the lower jaw when the mouth closed, producing a powerful shearing action,[2] which would have enabled dicynodonts to cope with tough plant material. Many genera also have a pair of tusks, which it is thought may have been an example of sexual dimorphism.[3]

The body is short, strong and barrel-shaped, with strong limbs. In large genera (such as Dinodontosaurus) the hindlimbs were held erect, but the forelimbs bent at the elbow. Both the pectoral girdle and the ilium are large and strong. The tail is short.

History

Dicynodonts have been known since the mid-1800s. South African geologist Andrew Geddes Bain gave the first description of dicynodonts in 1845. At the time, Bain was a supervisor for the construction of military roads under the Corps of Royal Engineers and had found many reptilian fossils during his surveys of South Africa. Bain described these fossils in an 1845 letter published in Transactions of the Geological Society of London, calling them "bidentals" for their two prominent tusks.[4] In that same year, English paleontologist Richard Owen named two species of dicynodonts from South Africa: Dicynodon lacerticeps and Dicynodon bainii. Since Bain was preoccupied with the Corps of Royal Engineers, he wanted Owen to describe his fossils more extensively. Owen did not publish a description until 1876 in his Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum.[5] By this time, many more dicynodonts had been described. In 1859, another important species called Ptychognathus declivis was named from South Africa. A year later, in 1860, Owen named the group Dicynodontia.[6] In his Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue, Owen honored Bain by erecting Bidentalia as a replacement name for his Dicynodontia.[5] The name Bidentalia quickly fell out of use in the following years, replaced by popularity of Owen's Dicynodontia.[7]

Evolutionary history

Dicynodonts first appear during Middle Permian, and underwent a rapid evolutionary radiation, becoming the most successful and abundant land vertebrates of the Late Permian. During this time they included a large variety of ecotypes, including large, medium-sized, and small herbivores and short-limbed mole-like burrowers.

Only four lineages are known to survived the end Permian extinction; the first three represented with a single genus each; Myosaurus, Kombuisia and Lystrosaurus, the latter being the most common and widespread herbivores of the Induan (earliest Triassic). None of these survived long into the Triassic. The fourth group was the Kannemeyeriiformes, the only dicynodonts who diversified during the Triassic.[8] These stocky, pig- to ox-sized animals were the most abundant herbivores worldwide from the Olenekian to the Ladinian age. By the Carnian they had been supplanted by traversodont cynodonts and rhynchosaur reptiles. During the Norian (middle of the Late Triassic), perhaps due to increasing aridity, they drastically declined, and the role of large herbivore was taken over by sauropodomorph dinosaurs.

Fossils discovered in Poland indicate that dicynodonts survived at least until the early Rhaetian (latest Triassic).[9] Six fragments of fossil bone interpreted as remains of a skull discovered in Australia (Queensland) might indicate that dicynodonts survived into the Cretaceous in southern Gondwana.[1] However, Agnolin et al. (2010) considered the affinities of the specimen from Australia to be uncertain, and noted its similarity to the skull bones of some baurusuchian crocodyliforms, such as Baurusuchus pachecoi.[10]

With the decline and extinction of the kannemeyerids, there were to be no more dominant large synapsid herbivores until the middle Paleocene epoch (60 Ma) when mammals, descendants of cynodonts, began to diversify after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Systematics

Taxonomy

Dicynodontia was originally named by English paleontologist Richard Owen. It was erected as a family of the order Anomodontia and included the genera Dicynodon and Ptychognathus. Other families of Anomodontia included Gnathodontia, which included Rhynchosaurus (now known to be an archosauromorph) and Cryptodontia, which included Oudenodon. Cryptodonts were distinguished from dicynodonts from their absence of tusks. Although it lacks tusks, Oudenodon is now classified as a dicynodont, and the name Cryptodontia is no longer used. Thomas Henry Huxley revised Owen's Dicynodontia as an order that included Dicynodon and Oudenodon.[11] Dicynodontia was later ranked as a suborder or infraorder with the larger group Anomodontia, which is classified as an order. The ranking of Dicynodontia has varied in recent studies, with Ivakhnenko (2008) considering it a suborder, Ivanchnenko (2008) considering it an infraorder, and Kurkin (2010) considering it an order.[12]

Many higher taxa, including infraorders and families, have been erected as a means of classifying the large number of dicynodont species. Cluver and King (1983) recognized several main groups within Dicynodontia, including Diictodontia, Endothiodontia, Eodicynodontia, Kingoriamorpha, Pristerodontia, and Venyukoviamorpha.[13] Many families have been proposed, including Cistecephalidae, Diictodontidae, Dicynodontidae, Emydopidae, Endothiodontidae, Kannemeyeriidae, Kingoriidae, Lystrosauridae, Myosauridae, Oudenodontidae, Pristerodontidae, and Robertiidae. However, with the rise of phylogenetics, most of these taxa are no longer considered valid. Kammerer and Angielczyk (2009) suggested that the problematic taxonomy and nomenclature of Dicynodontia and other groups results from the large number of conflicting studies and the tendency for invalid names to be mistakenly established.[7]

- Infraorder Dicynodontia

- Genus Angonisaurus

- Genus Colobodectes

- Superfamily Eodicynodontoidea

- Family Eodicynodontidae

- Superfamily Kingorioidea

- Family Kingoriidae

- Clade Diictodontia

- Superfamily Emydopoidea

- Family Cistecephalidae

- Family Emydopidae

- Genus Myosauroides

- Genus Myosaurus

- Genus Palemydops

- Superfamily Robertoidea

- Family Diictodontidae

- Family Robertiidae

- Genus Robertia

- Superfamily Emydopoidea

- Clade Pristerodontia

- Genus Dinanomodon

- Genus Odontocyclops

- Genus Propelanomodon

- Family Aulacocephalodontidae

- Family Dicynodontidae

- Genus Dicynodon

- Family Lystrosauridae

- Genus Kwazulusaurus

- Genus Lystrosaurus

- Family Oudenodontidae

- Genus Cteniosaurus

- Genus Oudenodon

- Genus Tropidostoma

- Genus Rhachiocephalus

- Family Pristerodontidae

- Superfamily Kannemeyeriiformes

- Family Kannemeyeriidae

- Genus Dinodontosaurus

- Genus Dolichuranus

- Genus Ischigualastia

- Genus Kannemeyeria

- Genus Placerias

- Genus Rabidosaurus

- Genus Sinokannemeyeria

- Family Shansiodontidae

- Family Stahleckeriidae

- Family Kannemeyeriidae

Unknown placement:

- Genus Moghreberia

- Genus Wadiasaurus

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram modified from Angielczyk and Rubidge (2010) showing the phylogenetic relationships of Dicynodontia:[14]

| Dicynodontia | |

See also

References

- ^ a b Thulborn, T.; Turner, S. (2003). "The last dicynodont: an Australian Cretaceous relict". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1518): 985–993. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2296. JSTOR 3558635.

- ^ Crompton, A. W, and Hotton, N. 1967. Functional morphology of the masticatory apparatus of two dicynodonts (Reptilia, Therapsida). Postilla, 109:1–51

- ^ Colbert, E. H., (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.), p. 137

- ^ Bain, A.G. (1845). "On the discovery of fossil remains of bidental and other reptiles in South Africa". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 1: 53–59. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1845.001.01.72.

- ^ a b Owen, R. (1876). Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the Collection of the British Museum. London: British Museum. p. 88.

- ^ Owen, R. (1860). "On the orders of fossil and recent Reptilia, and their distribution in time". Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 1859: 153–166.

- ^ a b Kammerer, C.F.; Angielczyk, K.D. (2009). "A proposed higher taxonomy of anomodont therapsids" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2018: 1–24.

- ^ On the Validity and Phylogenetic Position of Eubrachiosaurus browni, a Kannemeyeriiform Dicynodont (Anomodontia) from Triassic North America

- ^ Jerzy Dzik, Tomasz Sulej, and Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki (2008). "A dicynodont−theropod association in the latest Triassic of Poland". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (4): 733–738. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agnolin, F. L.; Ezcurra, M. D.; Pais, D. F.; Salisbury, S. W. (2010). "A reappraisal of the Cretaceous non-avian dinosaur faunas from Australia and New Zealand: Evidence for their Gondwanan affinities". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (2): 257–300. doi:10.1080/14772011003594870.

- ^ Osborn, H.F. (1904). "Reclassification of the Reptilia". The American Naturalist. 38 (446): 93–115. doi:10.1086/278383.

- ^ Kurkin, A.A. (2010). "Late Permian dicynodonts of Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 44 (6): 72–80. doi:10.1134/S0031030110060092.

- ^ Cluver, M.A.; King, G.M. (1983). "A reassessment of the relationships of Permian Dicynodontia (Reptilia, Therapsida) and a new classification of dicynodont". Annals of the South African Museum. 91: 195–273.

- ^ Kenneth D. Angielczyk; Bruce S. Rubidge (2010). "A new pylaecephalid dicynodont (Therapsida, Anomodontia) from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, Karoo Basin, Middle Permian of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (5): 1396–1409. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.501447.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Cox, B., Savage, R.J.G., Gardiner, B., Harrison, C. and Palmer, D. (1988) The Marshall illustrated encyclopedia of dinosaurs & prehistoric animals, 2nd Edition, Marshall Publishing

- King, Gillian M., "Anomodontia" Part 17 C, Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology, Gutsav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart and New York, 1988

- -- --, 1990, the Dicynodonts: A Study in Palaeobiology, Chapman and Hall, London and New York