Dilophosaurus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

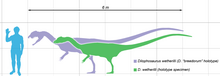

'''''Dilophosaurus''''' ({{IPAc-en|d|aɪ|ˌ|l|oʊ|f|ə|ˈ|s|ɔːr|ə|s|,_|-|f|oʊ|-}}{{refn|{{OxfordDictionaries.com|accessdate=2016-01-21|Dilophosaurus}}}} {{respell|dy|LOHF|o|SOR|əs}}) is a [[genus]] of [[theropod]] [[dinosaur]] that lived in what is now North America during the [[Early Jurassic]] [[period (geology)|Period]], about 193 million years ago. In 1942, three skeletons were found in [[Northern Arizona]], the two most complete of which were collected. The most complete of these was made the [[holotype specimen]] of a new species of the genus ''[[Megalosaurus]]'', named '''''M. wetherilli''''' by [[Samuel Welles]] in 1954. Welles found a larger skeleton belonging to the same species in 1964, and realized it bore crests on its skull, and therefore moved the species to the new genus ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1970. The genus name means "two-crested lizard", and the species name honors John Wetherill, a [[Navajo]] councilor. More specimens have since been found, including an infant, and |

'''''Dilophosaurus''''' ({{IPAc-en|d|aɪ|ˌ|l|oʊ|f|ə|ˈ|s|ɔːr|ə|s|,_|-|f|oʊ|-}}{{refn|{{OxfordDictionaries.com|accessdate=2016-01-21|Dilophosaurus}}}} {{respell|dy|LOHF|o|SOR|əs}}) is a [[genus]] of [[theropod]] [[dinosaur]] that lived in what is now North America during the [[Early Jurassic]] [[period (geology)|Period]], about 193 million years ago. In 1942, three skeletons were found in [[Northern Arizona]], the two most complete of which were collected. The most complete of these was made the [[holotype specimen]] of a new species of the genus ''[[Megalosaurus]]'', named '''''M. wetherilli''''' by [[Samuel Welles]] in 1954. Welles found a larger skeleton belonging to the same species in 1964, and realized it bore crests on its skull, and therefore moved the species to the new genus ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1970. The genus name means "two-crested lizard", and the species name honors John Wetherill, a [[Navajo]] councilor. More specimens have since been found, including an infant, and footprints have also bee attributed to the animal. Another species from China, ''D. sinensis'', was named in 1993, but was later found to belong to the genus ''[[Sinosaurus]]''. |

||

At about {{convert|7|m|ft|sp=us}} in length, with a weight of about {{convert|400|kg|lb}}, ''Dilophosaurus'' was one of the first big predatory dinosaurs, though it was smaller than later theropods. It was lightly built and slender, and though the skull was proportionally large, it was delicate. The snout was narrow, and the upper jaw had a gap below the nostril. It had a pair of longitudinal crests on its skull, similar to a [[cassowary]] with two crests. The mandible was slender and delicate at the front, but deep at the back. The teeth were long, curved, thin, and compressed sideways. The teeth of the lower jaw were much smaller than those of the upper jaw. The teeth had serrations at their front and back edges, and were covered in [[enamel]]. The neck was long, and its vertebrae were hollow, and very light. The arms were powerful, with a long and slender upper arm bone. The hands had four fingers; the first was short but strong and bore a large claw, the two following fingers were longer and more slender with smaller claws, and the fourth was [[vestigial]]. The feet were stout and the toes bore large claws. |

At about {{convert|7|m|ft|sp=us}} in length, with a weight of about {{convert|400|kg|lb}}, ''Dilophosaurus'' was one of the first big predatory dinosaurs, though it was smaller than later theropods. It was lightly built and slender, and though the skull was proportionally large, it was delicate. The snout was narrow, and the upper jaw had a gap below the nostril. It had a pair of longitudinal crests on its skull, similar to a [[cassowary]] with two crests. The [[mandible]] was slender and delicate at the front, but deep at the back. The teeth were long, curved, thin, and compressed sideways. The teeth of the lower jaw were much smaller than those of the upper jaw. The teeth had serrations at their front and back edges, and were covered in [[enamel]]. The neck was long, and its vertebrae were hollow, and very light. The arms were powerful, with a long and slender upper arm bone. The hands had four fingers; the first was short but strong and bore a large claw, the two following fingers were longer and more slender with smaller claws, and the fourth was [[vestigial]]. The feet were stout and the toes bore large claws. |

||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

''Dilophosaurus'' has been described as a medium-sized theropod.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> It was one of the first big predatory [[dinosaurs]], though small compared to some of the later [[theropods]]. It was lightly built, slender, and has been compared to a [[brown bear]] in size.<ref name="Naish"/><ref name=GSP88a>{{cite book |last=Paul |first=G. S. |title=Predatory Dinosaurs of the World |year=1988 |publisher=Simon & Schuster | pages = 258, 267–271 |location=New York |isbn=978-0-671-61946-6 }}</ref><ref name="holtz">{{cite book|last=Holtz|first=T. R. Jr.|year=2012|title=Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages |publisher=Random House|page=81|isbn=978-0-375-82419-7}}</ref> The largest known specimen measured about {{convert|7|m|ft|sp=us}} in length, its skull was {{convert|590|mm|ft|sp=us}} long, and it weighed about {{convert|400|kg|lb}}. The smaller [[holotype]] specimen was about {{convert|6.03|m|ft|sp=us}} long, with a hip height of about {{convert|1.36|m|ft|sp=us}}, its skull was {{convert|523|mm|ft|sp=us}} long, and it weighed about {{convert|283|kg|lb}}.<ref name=GSP88a/><ref name="paul2010">{{cite book | title=The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs | publisher=Princeton University Press | last=Paul | first=G. S. | authorlink=Gregory S. Paul | year=2010 | pages=75 | isbn=978-0-691-13720-9}}</ref> A resting trace of a large theropod that may be ''Dilophosaurus'' or a similar theropod has markings around the belly and feet that have been interpreted as feather impressions by some researchers. Others have concluded that the markings are [[sedimentological]] artifacts, while noting that this interpretation does not rule out that the track maker bore feathers.<ref name="Martin">{{cite journal|title=A THEROPOD RESTING TRACE THAT IS ALSO A LOCOMOTION TRACE: CASE STUDY OF HITCHCOCK'S SPECIMEN AC 1/7|journal=Gsa.confex.com|date=2004|url=https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2004NE/finalprogram/abstract_69779.htm}}</ref><ref name="Kundrát">{{cite journal|last1=Kundrát|first1=M.|title=When did theropods become feathered?-evidence for pre-archaeopteryx feathery appendages|journal=Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution|date=2004|volume=302B|issue=4|pages=355–364|doi=10.1002/jez.b.20014}}</ref><ref name="Lockley">{{cite journal|last1=Lockley|first1=M.|last2=Matsukawa|first2=Masaki|last3=Jianjun|first3=Li|title=Crouching Theropods in Taxonomic Jungles: Ichnological and Ichnotaxonomic Investigations of Footprints with Metatarsal and Ischial Impressions|journal=Ichnos|date=2003|volume=10|issue=2–4|pages=169–177|doi=10.1080/10420940390256249}}</ref> |

''Dilophosaurus'' has been described as a medium-sized theropod.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> It was one of the first big predatory [[dinosaurs]], though small compared to some of the later [[theropods]]. It was lightly built, slender, and has been compared to a [[brown bear]] in size.<ref name="Naish"/><ref name=GSP88a>{{cite book |last=Paul |first=G. S. |title=Predatory Dinosaurs of the World |year=1988 |publisher=Simon & Schuster | pages = 258, 267–271 |location=New York |isbn=978-0-671-61946-6 }}</ref><ref name="holtz">{{cite book|last=Holtz|first=T. R. Jr.|year=2012|title=Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages |publisher=Random House|page=81|isbn=978-0-375-82419-7}}</ref> The largest known specimen measured about {{convert|7|m|ft|sp=us}} in length, its skull was {{convert|590|mm|ft|sp=us}} long, and it weighed about {{convert|400|kg|lb}}. The smaller [[holotype]] specimen was about {{convert|6.03|m|ft|sp=us}} long, with a hip height of about {{convert|1.36|m|ft|sp=us}}, its skull was {{convert|523|mm|ft|sp=us}} long, and it weighed about {{convert|283|kg|lb}}.<ref name=GSP88a/><ref name="paul2010">{{cite book | title=The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs | publisher=Princeton University Press | last=Paul | first=G. S. | authorlink=Gregory S. Paul | year=2010 | pages=75 | isbn=978-0-691-13720-9}}</ref> A resting trace of a large theropod that may be ''Dilophosaurus'' or a similar theropod has markings around the belly and feet that have been interpreted as feather impressions by some researchers. Others have concluded that the markings are [[sedimentological]] artifacts, while noting that this interpretation does not rule out that the track maker bore feathers.<ref name="Martin">{{cite journal|title=A THEROPOD RESTING TRACE THAT IS ALSO A LOCOMOTION TRACE: CASE STUDY OF HITCHCOCK'S SPECIMEN AC 1/7|journal=Gsa.confex.com|date=2004|url=https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2004NE/finalprogram/abstract_69779.htm}}</ref><ref name="Kundrát">{{cite journal|last1=Kundrát|first1=M.|title=When did theropods become feathered?-evidence for pre-archaeopteryx feathery appendages|journal=Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution|date=2004|volume=302B|issue=4|pages=355–364|doi=10.1002/jez.b.20014}}</ref><ref name="Lockley">{{cite journal|last1=Lockley|first1=M.|last2=Matsukawa|first2=Masaki|last3=Jianjun|first3=Li|title=Crouching Theropods in Taxonomic Jungles: Ichnological and Ichnotaxonomic Investigations of Footprints with Metatarsal and Ischial Impressions|journal=Ichnos|date=2003|volume=10|issue=2–4|pages=169–177|doi=10.1080/10420940390256249}}</ref> |

||

''Dilophosaurus'' had 9 cervical (neck) vertebrae, 5 pectoral vertebrae (the vertebrae that transition between those of the neck and the back), 10 dorsal (back) vertebrae, and 45 caudal (tail) vertebrae. It had a long neck, which was probably flexed nearly 90° by the skull and by the shoulder, thereby holding the skull in a horizontal posture. The cervical vertebrae were unusually light; their centra (the "bodies" of the vertebrae) were hollowed out by pleurocoels (depressions on the sides) and centrocoels (cavities on the inside). The arches of the cervical vertebrae also had chonoses, conical recesses so large that the bones separating them were sometimes paper-thin. The centra were plano-concave, flat at the font and cupped (or concave) at the back. This indicates that the neck was flexible, though it had long, overlapping cervical ribs, which were fused to the centra. The cervical ribs were slender, and may therefore have bent easily. The [[atlas bone]] (the first cervical vertebra which attaches to the skull) had a small, cubic centrum, and had a concavity at the front where it formed a cup for the [[occipital condyle]] (protuberance which connects with the atlas vertebra) at the back of the skull. The [[axis bone]] (the second cervical vertebra) had a heavy spine, and its postzygapophyses were met by long prezygapophyses that curved upwards from the third cervical vertebra. The centra and spines of the cervical vertebrae were long and low, and the spines had caps which gave the appearance of a [[Maltese cross]] when seen from above. The neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae were also low and expanded front and back, which formed strong attachments for [[ligaments]]. There were four [[sacral vertebrae]] (dorsal vertebrae between the hips), which occupied the length of the [[ilium (bone)|ilium]] blade, and these did not appear to be fused. The centra of the caudal vertebrae were very consistent in length, but their diameter became smaller towards the back, and they went from elliptical to circular in cross-section.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> |

''Dilophosaurus'' had 9 cervical (neck) vertebrae, 5 pectoral vertebrae (the vertebrae that transition between those of the neck and the back), 10 dorsal (back) vertebrae, and 45 caudal (tail) vertebrae. It had a long neck, which was probably flexed nearly 90° by the skull and by the shoulder, thereby holding the skull in a horizontal posture. The cervical vertebrae were unusually light; their centra (the "bodies" of the vertebrae) were hollowed out by pleurocoels (depressions on the sides) and centrocoels (cavities on the inside). The arches of the cervical vertebrae also had chonoses, conical recesses so large that the bones separating them were sometimes paper-thin. The centra were plano-concave, flat at the font and cupped (or concave) at the back. This indicates that the neck was flexible, though it had long, overlapping cervical ribs, which were fused to the centra. The cervical ribs were slender, and may therefore have bent easily. The [[atlas bone]] (the first cervical vertebra which attaches to the skull) had a small, cubic centrum, and had a concavity at the front where it formed a cup for the [[occipital condyle]] (protuberance which connects with the atlas vertebra) at the back of the skull. The [[axis bone]] (the second cervical vertebra) had a heavy spine, and its [[postzygapophyses]] (articular processes) were met by long prezygapophyses that curved upwards from the third cervical vertebra. The centra and spines of the cervical vertebrae were long and low, and the spines had caps which gave the appearance of a [[Maltese cross]] when seen from above. The neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae were also low and expanded front and back, which formed strong attachments for [[ligaments]]. There were four [[sacral vertebrae]] (dorsal vertebrae between the hips), which occupied the length of the [[ilium (bone)|ilium]] blade, and these did not appear to be fused. The centra of the caudal vertebrae were very consistent in length, but their diameter became smaller towards the back, and they went from elliptical to circular in cross-section.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> |

||

[[File:Dilophosaurus forelimb orientation.PNG|thumb|upright|Diagram showing the forelimb of ''Dilophosaurus'' in hypothesized resting posture]] |

[[File:Dilophosaurus forelimb orientation.PNG|thumb|upright|Diagram showing the forelimb of ''Dilophosaurus'' in hypothesized resting posture]] |

||

The [[scapulae]] (shoulder blades) were moderate in length, wide (particularly the upper part), and were concave on their inner sides to follow the body's curvature. The [[coracoids]] were elliptical, and not fused to the scapulae. The arms were powerful, and had deep pits and stout processes for attachment of muscles and ligaments. The [[humerus]] (upper arm bone) was large and slender, with stout epipodials, and the ulna (lower arm bone) was stout and straight, with a stout [[olecranon]]. The hands had four fingers; the first was shorter but stronger than the following two fingers, with a large claw, and the two following fingers were longer and more slender, with smaller claws. The third finger was reduced, and the fourth was [[vestigial]] (was retained, but without function). The [[Iliac crest|crest]] of the ilium was highest over the peduncle, and its outer side was concave. The foot of the [[pubic bone]] was only slightly expanded, whereas the lower end was much more expanded on the [[ischium]], which also had a very thin shaft. The hind-legs were large, with a slighter longer [[femur]] (thigh bone) than [[tibia]] (lower leg bone), the opposite of for example ''[[Coelophysis]]''. The femur was massive, its shaft was [[Sigmoid function|sigmoid]]-shaped, and its [[greater trochanter]] was centered on the shaft. The tibia had a developed [[Tuberosity of the tibia|tuberosity]] and was expanded at the lower end. The [[astragalus bone]] (ankle bone) was separated from the tibia and the [[calcaneum]], and formed half of the socket for the fibula. It had long, stout feet with three well-developed toes that bore large claws. The third toe was the stoutest, and the smaller first toe (the [[hallux]]) was kept off the ground.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Welles|first1=S. P.|title=Two Centers of Ossification in a Theropod Astragalus|journal=Journal of Paleontology|date=1983|volume=57|issue=2|pages=401–401|jstor=1304663}}</ref> |

The [[scapulae]] (shoulder blades) were moderate in length, wide (particularly the upper part), and were concave on their inner sides to follow the body's curvature. The [[coracoids]] were elliptical, and not fused to the scapulae. The arms were powerful, and had deep pits and stout processes for attachment of muscles and ligaments. The [[humerus]] (upper arm bone) was large and slender, with stout epipodials, and the ulna (lower arm bone) was stout and straight, with a stout [[olecranon]]. The hands had four fingers; the first was shorter but stronger than the following two fingers, with a large claw, and the two following fingers were longer and more slender, with smaller claws. The third finger was reduced, and the fourth was [[vestigial]] (was retained, but without function). The [[Iliac crest|crest]] of the ilium was highest over the peduncle, and its outer side was concave. The foot of the [[pubic bone]] was only slightly expanded, whereas the lower end was much more expanded on the [[ischium]], which also had a very thin shaft. The hind-legs were large, with a slighter longer [[femur]] (thigh bone) than [[tibia]] (lower leg bone), the opposite of for example ''[[Coelophysis]]''. The femur was massive, its shaft was [[Sigmoid function|sigmoid]]-shaped, and its [[greater trochanter]] was centered on the shaft. The tibia had a developed [[Tuberosity of the tibia|tuberosity]] and was expanded at the lower end. The [[astragalus bone]] (ankle bone) was separated from the tibia and the [[calcaneum]], and formed half of the socket for the fibula. It had long, stout feet with three well-developed toes that bore large claws. The third toe was the stoutest, and the smaller first toe (the [[hallux]]) was kept off the ground.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Welles|first1=S. P.|title=Two Centers of Ossification in a Theropod Astragalus|journal=Journal of Paleontology|date=1983|volume=57|issue=2|pages=401–401|jstor=1304663}}</ref> |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

===Skull=== |

===Skull=== |

||

[[File:Dilophosaurus skull.jpg|thumb|left|Reconstructed skull and neck, [[Royal Tyrrell Museum]]; the crests and the gap in the upper jaw are distinguishing features of this dinosaur]] |

[[File:Dilophosaurus skull.jpg|thumb|left|Reconstructed skull and neck, [[Royal Tyrrell Museum]]; the crests and the gap in the upper jaw are distinguishing features of this dinosaur]] |

||

The skull of ''Dilophosaurus'' was large in proportion to the skeleton, yet delicate. The snout was narrow in front view, and narrowing towards the rounded top. The [[premaxilla]] (front bone of the upper jaw) was long and low when seen from the side, and its outer surface became less convex from snout to naris (bony nostril). The nostrils were placed further back than in most other theropods. The premaxilla was weakly attached to the [[maxilla]] (the following bone of the upper jaw), only connecting at the middle of the palate, with no connection art the side. Hindwards and below, the premaxilla formed a wall for a gap between itself and the maxilla, called the subnarial gap (also called "kink" or "notch"). Within the gap was a deep excavation behind the toothrow of the premaxilla, called the subnarial pit, which was walled by a downwards keel of the premaxilla. The outer surface of the premaxilla was covered in [[foramina]] (openings) of varying sizes. The nasal process (backwards projection from the premaxilla) was long and low, and formed most of the upper border of the elongated naris. It had a dip towards the font, which made the area by its base concave in profile. Seen from below, the premaxilla had an oval area which contained [[Dental alveolus|alveoli]] (tooth sockets). The maxilla was shallow, and was depressed around the antorbital fenestra, forming a recess that was rounded towards the front, and smoother than the rest of the maxilla. A foramen called the preantorbital fenestra opened into this recess at the front bend. Large foramina ran on the side of the maxilla, above the alveoli. A deep nutrient groove ran backwards from the subnarial pit along the base of the [[interdental plates]] (or rugosae) of the maxilla.<ref name="welles_s_1984">{{cite journal|author=Welles, S. P.|year=1984|title =''Dilophosaurus wetherilli'' (Dinosauria, Theropoda), osteology and comparisons|journal =Palaeontographica Abteilung A|volume=185|pages=85–180}}</ref><ref name="Welles1970"/><ref name=GSP88a/> |

The skull of ''Dilophosaurus'' was large in proportion to the skeleton, yet delicate. The snout was narrow in front view, and narrowing towards the rounded top. The [[premaxilla]] (front bone of the upper jaw) was long and low when seen from the side, and its outer surface became less convex from snout to naris (bony nostril). The nostrils were placed further back than in most other theropods. The premaxilla was weakly attached to the [[maxilla]] (the following bone of the upper jaw), only connecting at the middle of the palate, with no connection art the side. Hindwards and below, the premaxilla formed a wall for a gap between itself and the maxilla, called the subnarial gap (also called a "kink" or "notch"). Within the gap was a deep excavation behind the toothrow of the premaxilla, called the subnarial pit, which was walled by a downwards keel of the premaxilla. The outer surface of the premaxilla was covered in [[foramina]] (openings) of varying sizes. The nasal process (backwards projection from the premaxilla) was long and low, and formed most of the upper border of the elongated naris. It had a dip towards the font, which made the area by its base concave in profile. Seen from below, the premaxilla had an oval area which contained [[Dental alveolus|alveoli]] (tooth sockets). The maxilla was shallow, and was depressed around the [[antorbital fenestra]] (a large opening in front of the eye), forming a recess that was rounded towards the front, and smoother than the rest of the maxilla. A foramen called the preantorbital fenestra opened into this recess at the front bend. Large foramina ran on the side of the maxilla, above the alveoli. A deep nutrient groove ran backwards from the subnarial pit along the base of the [[interdental plates]] (or rugosae) of the maxilla.<ref name="welles_s_1984">{{cite journal|author=Welles, S. P.|year=1984|title =''Dilophosaurus wetherilli'' (Dinosauria, Theropoda), osteology and comparisons|journal =Palaeontographica Abteilung A|volume=185|pages=85–180}}</ref><ref name="Welles1970"/><ref name=GSP88a/> |

||

''Dilophosaurus'' bore two high and thin crests longitudinally on the skull roof, formed by the [[nasal bone|nasal]] and [[lacrimal bones]]. The paired crests extended upwards and gave the appearance of a [[cassowary]] with two crests. Each crest also had a finger-like backwards projection. The upper surface of the nasal bone between the crests was concave, and the nasal part of the crest overlapped the lacrimal part. As only one specimen preserves the shape of the crests, it is unknown if they differed in other individuals. The lacrimal bone had a thickened upper rim, where it formed the upper border at the back of the |

''Dilophosaurus'' bore two high and thin crests longitudinally on the skull roof, formed by the [[nasal bone|nasal]] and [[lacrimal bones]]. The paired crests extended upwards and gave the appearance of a [[cassowary]] with two crests. Each crest also had a finger-like backwards projection. The upper surface of the nasal bone between the crests was concave, and the nasal part of the crest overlapped the lacrimal part. As only one specimen preserves the shape of the crests, it is unknown if they differed in other individuals. The lacrimal bone had a thickened upper rim, where it formed the upper border at the back of the antorbital fenestra. The [[prefrontal bone]] formed the roof of the [[Orbit (anatomy)|orbit]] (eye socket), and had an L-shaped bar that made part of the upper surface of the orbit concave. The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The [[jugal bone]] had two upwards pointing processes, the first of which formed part of the lower margin of the antorbital fenestra, and part of the lower margin of the orbit. A projection from the [[quadrate bone]] into the [[lateral temporal fenestra]] (opening behind the eye) gave this a [[reniform]] (kidney-shaped) outline. The [[foramen magnum]] (the large opening at the back of the [[braincase]]) was about half the breadth of the occipital condyle, which was itself [[wikt:cordiform|cordiform]] (heart-shaped), and had a short neck and a groove on the side.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref name="Tetanurae"/><ref name="Welles1970"/> |

||

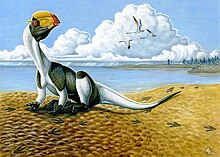

[[File:Dilophosaurus wetherilli.PNG|thumb|Restoration showing hypothetical feathers and crest-shape]] |

[[File:Dilophosaurus wetherilli.PNG|thumb|Restoration showing hypothetical feathers and crest-shape]] |

||

The mandible was slender and delicate at the front, but the articular region (where it connected with the skull) was massive, and the mandible was deep around the [[mandibular fenestra]] (an opening on |

The [[mandible]] was slender and delicate at the front, but the articular region (where it connected with the skull) was massive, and the mandible was deep around the [[mandibular fenestra]] (an opening on its side). The retroarticular process of the mandible (a backwards projection) was long, the [[surangular]] shelf was strongly horizontal. The [[dentary bone]] (the front part of the mandible where most of the teeth there attached) had an up-curved rather than pointed chin. The chin had a large foramen at the tip, and a row of small foramina ran in rough parallel with the upper edge of the dentary. On the inner side, the [[mandibular symphysis]] (where the two halves of the lower jaw connected) was flat and smooth, and showed no sign of being fused with its opposite half. A [[Meckelian foramen]] ran along the outer side of the dentary.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> |

||

''Dilophosaurus'' had 4 teeth in each premaxilla, 12 in each maxilla, and 17 in each dentary. The teeth were generally long, thin, and recurved, with relatively small bases. They were compressed sideways, oval in cross-section at the base, lenticular (lens-shaped) above, and slightly concave on their outer and inner sides. The teeth of the dentary were much smaller than those of the maxilla. The teeth had serrations on the front and back edges, which were offset by vertical grooves, and were smaller at the front. There were 31 to 41 serrations on the front edges, and 29 to 33 on the back. The teeth were covered in a thin layer of enamel, {{convert|0.1|to|0.15|mm|in}}, which extended far towards their bases. The alveoli were elliptical to almost circular, and all were larger than the bases of the teeth they contained, which may therefore have been loosely held in the jaws. Though the number of alveoli in the dentary indicates the teeth were very crowded, they were rather far apart, due to the larger size of their alveoli. The jaws contained [[replacement teeth]] at various stages of eruption. The interdental plates between the teeth were very low.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref name="gay_r_specimens"/> |

''Dilophosaurus'' had 4 teeth in each premaxilla, 12 in each maxilla, and 17 in each dentary. The teeth were generally long, thin, and recurved, with relatively small bases. They were compressed sideways, oval in cross-section at the base, lenticular (lens-shaped) above, and slightly concave on their outer and inner sides. The teeth of the dentary were much smaller than those of the maxilla. The teeth had serrations on the front and back edges, which were offset by vertical grooves, and were smaller at the front. There were 31 to 41 serrations on the front edges, and 29 to 33 on the back. The teeth were covered in a thin layer of [[enamel]], {{convert|0.1|to|0.15|mm|in|sp=us}}, which extended far towards their bases. The alveoli were elliptical to almost circular, and all were larger than the bases of the teeth they contained, which may therefore have been loosely held in the jaws. Though the number of alveoli in the dentary indicates the teeth were very crowded, they were rather far apart, due to the larger size of their alveoli. The jaws contained [[replacement teeth]] at various stages of eruption. The interdental plates between the teeth were very low.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref name="gay_r_specimens"/> |

||

==History of discovery== |

==History of discovery== |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

[[File:Dilophosaurus skeleton RTMoP.JPG|thumb|left|Reconstructed skeleton at RTM (based on the holotype), with outdated ([[pronated]]) hand pose]] |

[[File:Dilophosaurus skeleton RTMoP.JPG|thumb|left|Reconstructed skeleton at RTM (based on the holotype), with outdated ([[pronated]]) hand pose]] |

||

Welles and an assistant subsequently corrected the wall mount of the holotype specimen based on the new skeleton, by restoring the crests, redoing the pelvis, and making the neck ribs longer, and placed closer together. After studying the skeletons of North American theropods, and seeing most of the material in western Europe in 1969, Welles realized that the dinosaur did not belong to ''Megalosaurus'', and needed a new genus name. At this time, no other theropods with large longitudal crests on their heads were known, and the dinosaur had therefore gained interest by paleontologists. A mold of the holotype specimen was made, and fiberglass casts of it were distributed to various exhibits; to make labeling these casts easier, Welles decided to name the new genus in a brief note, rather than wait until the publication of a detailed description. In 1970, Welles coined the new genus name ''Dilophosaurus'', from the Greek words di (δι) meaning "two", lophos (λόφος) meaning "crest", and sauros (σαυρος) meaning "lizard"; "two-crested lizard". Welles published a detailed [[osteological]] description of ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1984, but the 1964 specimen has not yet been described.<ref name="Welles1970"/><ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref name="welles2"/><ref name="glut1997">{{Cite book| publisher = McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers| isbn = 978-0-375-82419-7| last = Glut| first = D. F.| title = Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia| year = 1997 |pages=347–350}}</ref><ref name="rauhut_2004">{{cite journal|last1=Rauhut|first1=O. W.|title=The Interrelationships and Evolution of Basal Theropod Dinosaurs |journal=The Palaeontological Association|date=2004|volume=69|pages=213|url=https://www.palass.org/publications/special-papers-palaeontology/archive/69/article_pp1-213|language=en}}</ref> ''Dilophosaurus'' was the first well-known theropod from the Early Jurassic, and remains one of the best preserved examples of that age.<ref name="Naish"/> |

Welles and an assistant subsequently corrected the wall mount of the holotype specimen based on the new skeleton, by restoring the crests, redoing the pelvis, and making the neck ribs longer, and placed closer together. After studying the skeletons of North American theropods, and seeing most of the material in western Europe in 1969, Welles realized that the dinosaur did not belong to ''Megalosaurus'', and needed a new genus name. At this time, no other theropods with large longitudal crests on their heads were known, and the dinosaur had therefore gained interest by paleontologists. A mold of the holotype specimen was made, and fiberglass casts of it were distributed to various exhibits; to make labeling these casts easier, Welles decided to name the new genus in a brief note, rather than wait until the publication of a detailed description. In 1970, Welles coined the new genus name ''Dilophosaurus'', from the Greek words di (δι) meaning "two", lophos (λόφος) meaning "crest", and sauros (σαυρος) meaning "lizard"; "two-crested lizard". Welles published a detailed [[osteological]] description of ''Dilophosaurus'' in 1984, but the 1964 specimen has not yet been described.<ref name="Welles1970"/><ref name="welles_s_1984"/><ref name="welles2"/><ref name="glut1997">{{Cite book| publisher = McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers| isbn = 978-0-375-82419-7| last = Glut| first = D. F.| title = Dinosaurs, the encyclopedia| year = 1997 |pages=347–350}}</ref><ref name="rauhut_2004">{{cite journal|last1=Rauhut|first1=O. W.|title=The Interrelationships and Evolution of Basal Theropod Dinosaurs |journal=The Palaeontological Association|date=2004|volume=69|pages=213|url=https://www.palass.org/publications/special-papers-palaeontology/archive/69/article_pp1-213|language=en}}</ref> ''Dilophosaurus'' was the first well-known theropod from the Early Jurassic, and remains one of the best preserved examples of that age.<ref name="Naish"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

In 1971 Welles reported dinosaur footprints from the Kayenta Formation, {{convert|45|ft|m|sp=us|order=flip}} and {{convert|367|ft|m|sp=us|order=flip}} below the level where the original ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens were found. The lower footprints were [[tridactyl]] (three-toed), and could have been made by ''Dilophosaurus''; Welles created the new [[ichnogenus]] ''Dilophosauripus williamsi'' based on them, in honor of Jesse Williams, the discoverer of the first ''Dilophosaurus'' skeletons. The type specimen is a cast of a large footprint catalogued as UCMP 79690-4, with casts of three other prints included in the hypodigm.<ref name="welles_1971">Welles, S.P. (1971). Dinosaur footprints from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona: Plateau, v. 44, pp. 27–38.</ref> |

|||

In 2001, the American paleontologist [[Robert J. Gay]] identified the remains of at least three new ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens (this number is based on the presence of three pubic bone fragments and two differentially sized femora) in the collections of the Museum of Northern Arizona. The specimens were found in 1978 in the Rock Head Quadrangle, {{convert|120|mi|km|sp=us|order=flip}} away from where the original specimens were found, and had been labeled as a "large theropod". Though most of the material is damaged, it is significant in including elements not preserved in the earlier known specimens, including part of the pelvis, and some ribs. Some elements in the collection belonged to an infant specimen (MNA P1.3181), the youngest known example of this genus, and one of the earliest known infant theropods from North America, only preceded by some ''Coelophysis'' specimens. The juvenile specimen includes a partial humerus, a partial fibula, and a tooth fragment.<ref name="gay_r_specimens">{{cite journal|author=Gay, Robert|year=2001|title=New specimens of ''Dilophosaurus wetherilli'' (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona|journal=Western Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists annual meeting volume Mesa, Arizona|volume =1|page=1}}</ref> In 2005, the American paleontologist Ronald S. Tykoski assigned a specimen (TMM 43646-140) from Gold Spring, Arizona, to ''Dilophosaurus'', but in 2012 the American paleontologist Matthew T. Carrano and colleagues found it to differ in some details.<ref name="Tykoski2005"/><ref name="Tetanurae"/> |

In 2001, the American paleontologist [[Robert J. Gay]] identified the remains of at least three new ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens (this number is based on the presence of three pubic bone fragments and two differentially sized femora) in the collections of the Museum of Northern Arizona. The specimens were found in 1978 in the Rock Head Quadrangle, {{convert|120|mi|km|sp=us|order=flip}} away from where the original specimens were found, and had been labeled as a "large theropod". Though most of the material is damaged, it is significant in including elements not preserved in the earlier known specimens, including part of the pelvis, and some ribs. Some elements in the collection belonged to an infant specimen (MNA P1.3181), the youngest known example of this genus, and one of the earliest known infant theropods from North America, only preceded by some ''Coelophysis'' specimens. The juvenile specimen includes a partial humerus, a partial fibula, and a tooth fragment.<ref name="gay_r_specimens">{{cite journal|author=Gay, Robert|year=2001|title=New specimens of ''Dilophosaurus wetherilli'' (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona|journal=Western Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists annual meeting volume Mesa, Arizona|volume =1|page=1}}</ref> In 2005, the American paleontologist Ronald S. Tykoski assigned a specimen (TMM 43646-140) from Gold Spring, Arizona, to ''Dilophosaurus'', but in 2012 the American paleontologist Matthew T. Carrano and colleagues found it to differ in some details.<ref name="Tykoski2005"/><ref name="Tetanurae"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In 1971 Welles reported dinosaur footprints from the Kayenta Formation, {{convert|45|ft|m|sp=us|order=flip}} and {{convert|367|ft|m|sp=us|order=flip}} below the level where the original ''Dilophosaurus'' specimens were found. The lower footprints were [[tridactyl]] (three-toed), and could have been made by ''Dilophosaurus''; Welles created the new [[ichnogenus]] ''Dilophosauripus williamsi'' based on them, in honor of Jesse Williams, the discoverer of the first ''Dilophosaurus'' skeletons. The type specimen is a cast of a large footprint catalogued as UCMP 79690-4, with casts of three other prints included in the hypodigm.<ref name="welles_1971">Welles, S.P. (1971). Dinosaur footprints from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona: Plateau, v. 44, pp. 27–38.</ref> In 1984 Welles conceded that there was no way to prove or disprove that the footprints belonged to ''Dilophosaurus''.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> [[Connecticut River Valley trackways|Tracks]] of ''Eubrontes'' and ''Gigandipus'' of the [[Connecticut River Valley]], which have been found in both Connecticut and in Massachusetts, have often been attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'',<ref name = "c-valley">{{cite web|url = http://www.nashdinosaurtracks.com/learn-about-local-dinosaurs.php |title= Dinosaur footprints of the Connecticut River Valley|publisher = Nash Dinosaur Track Site and Rock Shop}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://mentalfloss.com/article/60231/10-crested-facts-about-dilophosaurus |title=10 Crested Facts About Dilophosaurus |publisher=Mental Floss}}</ref> however no fossil remains of ''Dilophosaurus'' have been directly attributed to either one of the footprint types. The size and shape suggested they were made by a theropod around 20 feet long similar to that of ''Dilophosaurus'', suggesting they were either made by ''Dilophosaurus'' or a very close relative. Two similar footprints, ''Anchisauripus'' and ''Grallator'', also found in the valley, have often been attributed to ''Dilophosaur's'' smaller relatives, ''Podokesaurus'' and ''Coelophysis'', and occasionally attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'' itself.<ref name = "c-valley"/> |

||

In 1991, the Polish paleontologist Gerard Gierlinski examined tridactyl footprints from the [[Holy Cross Mountains]] in [[Poland]] and concluded they belonged to a theropod like ''Dilophosaurus''. He coined the new ichnospecies ''[[Grallator]]'' (''[[Eubrontes]]'') ''soltykovensis'' based on them, with a cast of footprint MGIW 1560.11.12 as the holotype.<ref>Gierlinski, G.(1991) New dinosaur ichnotaxa from the Early Jurassic of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimat.,Palaeoecol.,85(1–2): 137–148</ref> In 2009 the American paleontologists Andrew R. C. Milner and colleagues used the combination ''[[Kayentapus]] soltykovensis'' instead. They also suggested that ''Dilophosauripus'' may not be distinct from ''Eubrontes'' and ''Kayentapus'', as the long claw marks that distinguish ''Dilophosauripus'' may be an artifact of dragging. They found ''Dilophosaurus'' a suitable match for a [[trackway]] and resting trace (SGDS.18.T1) from the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site in the [[Moenave Formation]] of Utah, though the dinosaur is not itself known from the formation, which is slightly older than the Kayenta Formation.<ref name="Restingtrace">{{cite journal|last1=Milner|first1=A. R. C.|last2=Harris|first2=J. D.|last3=Lockley|first3=M. G.|last4=Kirkland|first4=J. I.|last5=Matthews|first5=N. A.|last6=Harpending|first6=H.|title=Bird-Like Anatomy, Posture, and Behavior Revealed by an Early Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Resting Trace|journal=PLoS ONE|date=2009|volume=4|issue=3|pages=e4591|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0004591}}</ref> |

|||

===Formerly assigned species=== |

===Formerly assigned species=== |

||

| Line 98: | Line 100: | ||

==Paleobiology== |

==Paleobiology== |

||

[[File:Dilophosaurus wetherilli.jpg|thumb|left|Restoration of ''Dilophosaurus'' in resting pose, based on |

[[File:Dilophosaurus wetherilli.jpg|thumb|left|Restoration of ''Dilophosaurus'' in resting pose, based on tracks at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site, Utah]] |

||

Welles envisioned ''Dilophosaurus'' as an active, clearly bipedal animal, similar to an enlarged [[ostrich]]. |

Welles envisioned ''Dilophosaurus'' as an active, clearly bipedal animal, similar to an enlarged [[ostrich]]. He found the forelimbs to have been powerful weapons, strong and flexible, and not used for locomotion. He noted that the hands were capable of grasping and slashing, of meeting each other, and reaching two thirds up the neck. He proposed that during a sitting posture, it would rest on the large "foot" of its ischium, as well as its tail and feet.<ref name="welles_s_1984"/> In 1990, the American paleontologists Stephen and Sylvia Czerkas suggested that the weak pelvis of ''Dilophosaurus'' could have been an adaptation for an aquatic life-style, where the water would help support its weight, and that it could have been an efficient swimmer. They found it doubtful that it would have been restricted to a watery environment, though, due to the strength and proportions of it hind-limbs, which would have made it fleet-footed and agile during bipedal locomotion.<ref name="Czerkas">{{cite book | last1 = Czerkas | first1 = S. J. | last2 = Czerkas | first2 = S. A. |year= 1990 | page = 208|title= Dinosaurs: a Global View |publisher= Dragons’ World |isbn=978-0792456063|location=Limpsfield}}</ref> |

||

In 2005, the American paleontologists Phil Senter and James H. Robins examined the range of motion in the forelimbs of ''Dilophosaurus'' and other theropods. They found that ''Dilophosaurus'' would have been able to hold its humerus almost parallel with its scapula, but not more horizontal than that. The elbow could approach full extension, but not achieve it completely, and not flex at a right angle. The fingers do not appear to have been voluntarily hyperextensible (able to extend backwards, beyond their normal range), but they may have been passively hyperextensible, to resist dislocation during violent movements by captured prey.<ref name="Motion">{{cite journal|last1=Senter|first1=P.|last2=Robins|first2=J. H.|title=Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis'', and implications for predatory behaviour|journal=Journal of Zoology|date=2005|volume=266|issue=3|pages=307–318|doi=10.1017/S0952836905006989}}</ref> A 2015 article by Senter and Robins gave recommendations of how to reconstruct forelimb pose in bipedal dinosaurs, based on examination of various taxa, including ''Dilophosaurus''. The scapulae were held very horizontally, the resting orientation of the elbow would have been close to a right angle, and the orientation of the hand would not have deviated much from that of the lower arm.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Senter|first1=P.|last2=Robins|first2=J. H.|title=Resting Orientations of Dinosaur Scapulae and Forelimbs: A Numerical Analysis, with Implications for Reconstructions and Museum Mounts|journal=Plos One|date=2015|volume=10|issue=12|pages=e0144036|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0144036|pmid=26675035|bibcode=2015PLoSO..1044036S}}</ref> |

In 2005, the American paleontologists Phil Senter and James H. Robins examined the range of motion in the forelimbs of ''Dilophosaurus'' and other theropods. They found that ''Dilophosaurus'' would have been able to hold its humerus almost parallel with its scapula, but not more horizontal than that. The elbow could approach full extension, but not achieve it completely, and not flex at a right angle. The fingers do not appear to have been voluntarily hyperextensible (able to extend backwards, beyond their normal range), but they may have been passively hyperextensible, to resist dislocation during violent movements by captured prey.<ref name="Motion">{{cite journal|last1=Senter|first1=P.|last2=Robins|first2=J. H.|title=Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur ''Acrocanthosaurus atokensis'', and implications for predatory behaviour|journal=Journal of Zoology|date=2005|volume=266|issue=3|pages=307–318|doi=10.1017/S0952836905006989}}</ref> A 2015 article by Senter and Robins gave recommendations of how to reconstruct forelimb pose in bipedal dinosaurs, based on examination of various taxa, including ''Dilophosaurus''. The scapulae were held very horizontally, the resting orientation of the elbow would have been close to a right angle, and the orientation of the hand would not have deviated much from that of the lower arm.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Senter|first1=P.|last2=Robins|first2=J. H.|title=Resting Orientations of Dinosaur Scapulae and Forelimbs: A Numerical Analysis, with Implications for Reconstructions and Museum Mounts|journal=Plos One|date=2015|volume=10|issue=12|pages=e0144036|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0144036|pmid=26675035|bibcode=2015PLoSO..1044036S}}</ref> |

||

| Line 111: | Line 113: | ||

In 1986, the American paleontologist [[Robert T. Bakker]] instead found ''Dilophosaurus'', with its massive neck and skull and large upper teeth, to have been adapted for killing large prey, and strong enough to attack any Early Jurassic herbivores.<ref name ="bakker86">{{cite book|title=The Dinosaur Heresies |year=1986|publisher=william Morrow|location= New York |pages=263–264}}</ref> In 1988, Paul dismissed the idea that ''Dilophosaurus'' was a scavenger, and claimed that scavenging terrestrial animals are a myth. He stated that the snout of ''Dilophosaurus'' was better braced than what had been thought previously, and that the very large, slender maxillary teeth were more lethal than the claws. Paul suggested that it hunted large animals such as [[prosauropods]], and that it was more capable of snapping small animals than other theropods of a similar size.<ref name=GSP88a/> Paul also depicted ''Dilophosaurus'' bouncing on its tail while lashing out at an enemy, similar to a [[kangaroo]].<ref name=ScientificAmerican>Multiple authors (2000). "Color section". pp. 216, In Paul, G.S. (ed.). ''The Scientific American book of dinosaurs''. St. Martin's Press, New York.</ref> |

In 1986, the American paleontologist [[Robert T. Bakker]] instead found ''Dilophosaurus'', with its massive neck and skull and large upper teeth, to have been adapted for killing large prey, and strong enough to attack any Early Jurassic herbivores.<ref name ="bakker86">{{cite book|title=The Dinosaur Heresies |year=1986|publisher=william Morrow|location= New York |pages=263–264}}</ref> In 1988, Paul dismissed the idea that ''Dilophosaurus'' was a scavenger, and claimed that scavenging terrestrial animals are a myth. He stated that the snout of ''Dilophosaurus'' was better braced than what had been thought previously, and that the very large, slender maxillary teeth were more lethal than the claws. Paul suggested that it hunted large animals such as [[prosauropods]], and that it was more capable of snapping small animals than other theropods of a similar size.<ref name=GSP88a/> Paul also depicted ''Dilophosaurus'' bouncing on its tail while lashing out at an enemy, similar to a [[kangaroo]].<ref name=ScientificAmerican>Multiple authors (2000). "Color section". pp. 216, In Paul, G.S. (ed.). ''The Scientific American book of dinosaurs''. St. Martin's Press, New York.</ref> |

||

In 2007, |

In 2007, Milner and [[James I. Kirkland]] suggested that ''Dilophosaurus'' had features that indicates it may have eaten fish. They pointed out that the ends of the jaws were expanded to the sides, forming a "[[Rosette (design)|rosette]]" of interlocking teeth, similar to those of [[spinosaurids]], which are known to have eaten fish, and the [[gharials]], which is the modern crocodile that eats most fish. The nasal openings were also retracted back on the jaws, similar to spinosaurids which have even more retracted nasal openings, and this may have limited water splashing into the nostrils during fishing. Both groups also had long arms with well-developed claws, which could help when catching fish. Lake Dixie, a large lake which extended from Utah to Arizona and Nevada, would have provided abundant fish in the "post-cataclysmic", biologically more impoverished world that followed the [[Triassic–Jurassic extinction event]].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Milner|first1=A.|last2=Kirkland|first2=J.|title=The case for fishing dinosaurs at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm|journal=Survey Notes of the Utah Geological Survey|date=2007|volume=39|pages=1–3|url=http://files.geology.utah.gov/surveynotes/articles/pdf/fishing_dinos_39-3.pdf}}</ref> |

||

===Crest function=== |

===Crest function=== |

||

| Line 141: | Line 143: | ||

===Paleoichnology=== |

===Paleoichnology=== |

||

[[File:Eubrontes resting trace.png|thumb|upright|Resting trace attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'', St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site]] |

[[File:Eubrontes resting trace.png|thumb|upright|Resting trace attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'', St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site]] |

||

The ''Dilophosauripus'' footprints described by Welles were all on the same level, and were described as a "chicken yard |

The ''Dilophosauripus'' footprints described by Welles were all on the same level, and were described as a "chicken yard hodge-podge" of footprints, with few forming a trackway. The footprints had been imprinted in mud, which allowed the feet to sink down {{convert|5–10|cm|in|sp=us}}. The prints were sloppy, and the varying breadth of the toe prints indicates mud had clung to the feet. The impressions varied to differences in the substrate and the manner they were made; sometimes the foot was planted directly, but there was often a backwards or forwards slip as the foot came down. The positions and angles of the toes also varied considerably, which indicates they must have been quite flexible. The ''Dilophosauripus'' footprints had an offset second toe with a thick base, and very long, straight claws which were were in line with the axes of the toe-pads. One of the footprints was missing the claw of the second toe, perhaps due to injury.<ref name="welles_1971"/> |

||

In 1991, trackway specialist Gerard Gierlinski re-examined tracks from the [[Holy Cross Mountains]] in [[Poland]] and renamed them ''Kayentapus soltykovensis'', concluding that the "dilophosaur" form was the most appropriate candidate for making these ichnotaxa.<ref>Gierlinski, G.(1991) New dinosaur ichnotaxa from the Early Jurassic of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimat.,Palaeoecol.,85(1–2): 137–148</ref> |

|||

Fossilized footprints, discovered in 200-million-year-old sedimentary rock, which were assigned to ''Dilophosaurus'' were discovered in the Höganäs Formation in Vallåkra, Sweden, during the 1970s. The footprints appears to show that these dinosaurs lived in herds.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.exempelbanken.se/system/documents/980191441/original/3228_vallakra.pdf |title=vallakra.pdf |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2017-06-11}}</ref> Fossilized footprints assigned to ''Dilophosaurus'' have also been discovered in Sala, Sweden. Other tracks discovered in the Höganäs Formation have been assigned to the ichnogenus ''Grallator (Eubrontes) cf. giganteus'', which were discovered in Rhaetian strata, and ''Grallator (Eubrontes) soltykovensis'', which were discovered in Hettangian strata.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Gierliński | first1 = G. | last2 = Ahlberg | first2 = A. | doi = 10.1080/10420949409386377 | title = Late triassic and early jurassic dinosaur footprints in the höganäs formation of southern Sweden | journal = Ichnos | volume = 3 | issue = 2 | page = 99 | year = 1994 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> A few of the tracks were taken to museums, but most of them disappeared in natural floodings.<ref>{{cite web|author=Kent Lungren |url=http://kentlundgren.blogspot.se/2012/03/kontakt-med-trias-och-jura.html |title=Tankar i tiden: Kontakt med Trias och Jura |publisher=Kentlundgren.blogspot.se |accessdate=2013-10-23}}</ref> In 1994, Gierlinski and Ahlberg assigned these tracks from the [[Hoganas Formation]] of Sweden to ''Dilophosaurus'' as well.<ref name="Glut_DTE_S1">Glut, D. F. (1999). Dinosaurs, the Encyclopedia, Supplement 1: McFarland & Company, Inc., 442pp.</ref> |

Fossilized footprints, discovered in 200-million-year-old sedimentary rock, which were assigned to ''Dilophosaurus'' were discovered in the Höganäs Formation in Vallåkra, Sweden, during the 1970s. The footprints appears to show that these dinosaurs lived in herds.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.exempelbanken.se/system/documents/980191441/original/3228_vallakra.pdf |title=vallakra.pdf |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2017-06-11}}</ref> Fossilized footprints assigned to ''Dilophosaurus'' have also been discovered in Sala, Sweden. Other tracks discovered in the Höganäs Formation have been assigned to the ichnogenus ''Grallator (Eubrontes) cf. giganteus'', which were discovered in Rhaetian strata, and ''Grallator (Eubrontes) soltykovensis'', which were discovered in Hettangian strata.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Gierliński | first1 = G. | last2 = Ahlberg | first2 = A. | doi = 10.1080/10420949409386377 | title = Late triassic and early jurassic dinosaur footprints in the höganäs formation of southern Sweden | journal = Ichnos | volume = 3 | issue = 2 | page = 99 | year = 1994 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> A few of the tracks were taken to museums, but most of them disappeared in natural floodings.<ref>{{cite web|author=Kent Lungren |url=http://kentlundgren.blogspot.se/2012/03/kontakt-med-trias-och-jura.html |title=Tankar i tiden: Kontakt med Trias och Jura |publisher=Kentlundgren.blogspot.se |accessdate=2013-10-23}}</ref> In 1994, Gierlinski and Ahlberg assigned these tracks from the [[Hoganas Formation]] of Sweden to ''Dilophosaurus'' as well.<ref name="Glut_DTE_S1">Glut, D. F. (1999). Dinosaurs, the Encyclopedia, Supplement 1: McFarland & Company, Inc., 442pp.</ref> |

||

Gierlinski (1996) observed unusual traces associated with a track specimen in the collection at the [[Beneski Museum of Natural History|Pratt Museum]] in Amherst, Massachusetts. Specimen AC 1/7 is a "dinosaur sitting imprint", made when a dinosaur is resting its body on the ground, leaving an impression of its belly between a pair of footprints. Traces associated with AC 1/7 were interpreted by Gierlinski as the imprints of feathers, suggesting that ''Dilophosaurus'' was a feathered dinosaur.<ref name="Glut_DTE_S1"/> Further analysis proved, however, that the lines that seemed to be feathers were in reality just cracks in the mud where the animal sat. While this does not rule out the possibility of feathery covering on this species, there is no evidence for it and it currently remains as speculation.<ref>Martin, A. J. & Rainforth, E. C. 2004. A theropod resting trace that is also a locomotion trace: case study of Hitchcock’s specimen AC 1/7. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs 36 (2), 96.</ref> |

Gierlinski (1996) observed unusual traces associated with a track specimen in the collection at the [[Beneski Museum of Natural History|Pratt Museum]] in Amherst, Massachusetts. Specimen AC 1/7 is a "dinosaur sitting imprint", made when a dinosaur is resting its body on the ground, leaving an impression of its belly between a pair of footprints. Traces associated with AC 1/7 were interpreted by Gierlinski as the imprints of feathers, suggesting that ''Dilophosaurus'' was a feathered dinosaur.<ref name="Glut_DTE_S1"/> Further analysis proved, however, that the lines that seemed to be feathers were in reality just cracks in the mud where the animal sat. While this does not rule out the possibility of feathery covering on this species, there is no evidence for it and it currently remains as speculation.<ref>Martin, A. J. & Rainforth, E. C. 2004. A theropod resting trace that is also a locomotion trace: case study of Hitchcock’s specimen AC 1/7. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs 36 (2), 96.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | [[Connecticut River Valley trackways|Tracks]] of ''Eubrontes'' and ''Gigandipus'' of the [[Connecticut River Valley]], which have been found in both Connecticut and in Massachusetts, have often been attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'',<ref name = "c-valley">{{cite web|url = http://www.nashdinosaurtracks.com/learn-about-local-dinosaurs.php |title= Dinosaur footprints of the Connecticut River Valley|publisher = Nash Dinosaur Track Site and Rock Shop}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://mentalfloss.com/article/60231/10-crested-facts-about-dilophosaurus |title=10 Crested Facts About Dilophosaurus |publisher=Mental Floss}}</ref> however no fossil remains of ''Dilophosaurus'' have been directly attributed to either one of the footprint types. The size and shape suggested they were made by a theropod around 20 feet long similar to that of ''Dilophosaurus'', suggesting they were either made by ''Dilophosaurus'' or a very close relative. Two similar footprints, ''Anchisauripus'' and ''Grallator'', also found in the valley, have often been attributed to ''Dilophosaur's'' smaller relatives, ''Podokesaurus'' and ''Coelophysis'', and occasionally attributed to ''Dilophosaurus'' itself.<ref name = "c-valley"/> |

||

==Paleoecology== |

==Paleoecology== |

||

| Line 169: | Line 167: | ||

| issue=2 | url=https://people.hofstra.edu/J_B_Bennington/publications/JPerrors.html}}</ref> Welles himself was "thrilled" to see ''Dilophosaurus'' in Jurassic Park, and though he noted the inaccuracies, he found them minor points and enjoyed the movie, and was happy to find the dinosaur "an internationally known actor".<ref name="wellesactor">{{cite web|url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/dilophosaur/actor.html|title=''Dilophosaurus'', the Actor|author=Welles, S.|work=ucmp.berkeley.edu|publisher=[[University of California, Berkeley]]|accessdate=2007-11-17|year=2007}}</ref> |

| issue=2 | url=https://people.hofstra.edu/J_B_Bennington/publications/JPerrors.html}}</ref> Welles himself was "thrilled" to see ''Dilophosaurus'' in Jurassic Park, and though he noted the inaccuracies, he found them minor points and enjoyed the movie, and was happy to find the dinosaur "an internationally known actor".<ref name="wellesactor">{{cite web|url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/dilophosaur/actor.html|title=''Dilophosaurus'', the Actor|author=Welles, S.|work=ucmp.berkeley.edu|publisher=[[University of California, Berkeley]]|accessdate=2007-11-17|year=2007}}</ref> |

||

In 2017, ''Dilophosaurus'' was designated as the [[state dinosaur]] of the US state of [[Connecticut]], to become official with the new state budget in 2019. ''Dilophosaurus'' was chosen because tracks thought to be made by a related dinosaur were discovered in [[Rocky Hill, Connecticut|Rocky Hill]] in 1966, during excavation for the [[Interstate Highway 91]]. The six tracks were assigned to the |

In 2017, ''Dilophosaurus'' was designated as the [[state dinosaur]] of the US state of [[Connecticut]], to become official with the new state budget in 2019. ''Dilophosaurus'' was chosen because tracks thought to be made by a related dinosaur were discovered in [[Rocky Hill, Connecticut|Rocky Hill]] in 1966, during excavation for the [[Interstate Highway 91]]. The six tracks were assigned to the ichnospecies ''Eubrontes giganteus'', which was therefore made the [[state fossil]] of Connecticut in 1991. The area they were found in had been a Triassic lake, and when the significance of the area was confirmed, the highway was rerouted, and the are was made a [[Connecticut state park]]; [[Dinosaur State Park]]. In 1981, a sculpture of ''Dilophosaurus'', the first life-sized reconstruction of this dinosaur, was donated to the state park.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Altimari|first1=Daniela|title=Bill Naming State Dinosaur Signed by the Governor|url=http://www.courant.com/politics/capitol-watch/hc-bill-naming-state-dinosaur-signed-by-the-governor-20170718-story.html|website=Hartford Courant|accessdate=21 July 2017}}</ref><ref name="Meg">{{cite news|last1=Stone|first1=M.|title=Connecticut Welcomes Its New State Dinosaur - CT Boom|url=http://ctboom.com/connecticut-welcomes-its-new-state-dinosaur/|work=ctboom.com}}</ref><ref name="Rogers">{{cite news|last1=Rogers|first1=O.|title=Discovered Dinosaur Tracks Re-Route Highway and Lead to State Park {{!}} ConnecticutHistory.org|url=https://connecticuthistory.org/discovered-dinosaur-tracks-re-route-highway-and-lead-to-state-park/|accessdate=3 January 2018|work=connecticuthistory.org|date=2016}}</ref><ref name=GSP88a/> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 05:52, 18 January 2018

| Dilophosaurus Temporal range: Early Jurassic,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed cast of the holotype specimen (UCMP 37302) in burial position, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Genus: | †Dilophosaurus Welles, 1970 |

| Species: | †D. wetherilli

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Welles, 1954)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Dilophosaurus (/daɪˌloʊfəˈsɔːrəs, -foʊ-/[1] dy-LOHF-o-SOR-əs) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now North America during the Early Jurassic Period, about 193 million years ago. In 1942, three skeletons were found in Northern Arizona, the two most complete of which were collected. The most complete of these was made the holotype specimen of a new species of the genus Megalosaurus, named M. wetherilli by Samuel Welles in 1954. Welles found a larger skeleton belonging to the same species in 1964, and realized it bore crests on its skull, and therefore moved the species to the new genus Dilophosaurus in 1970. The genus name means "two-crested lizard", and the species name honors John Wetherill, a Navajo councilor. More specimens have since been found, including an infant, and footprints have also bee attributed to the animal. Another species from China, D. sinensis, was named in 1993, but was later found to belong to the genus Sinosaurus.

At about 7 meters (23 ft) in length, with a weight of about 400 kilograms (880 lb), Dilophosaurus was one of the first big predatory dinosaurs, though it was smaller than later theropods. It was lightly built and slender, and though the skull was proportionally large, it was delicate. The snout was narrow, and the upper jaw had a gap below the nostril. It had a pair of longitudinal crests on its skull, similar to a cassowary with two crests. The mandible was slender and delicate at the front, but deep at the back. The teeth were long, curved, thin, and compressed sideways. The teeth of the lower jaw were much smaller than those of the upper jaw. The teeth had serrations at their front and back edges, and were covered in enamel. The neck was long, and its vertebrae were hollow, and very light. The arms were powerful, with a long and slender upper arm bone. The hands had four fingers; the first was short but strong and bore a large claw, the two following fingers were longer and more slender with smaller claws, and the fourth was vestigial. The feet were stout and the toes bore large claws.

Description

Dilophosaurus has been described as a medium-sized theropod.[2] It was one of the first big predatory dinosaurs, though small compared to some of the later theropods. It was lightly built, slender, and has been compared to a brown bear in size.[3][4][5] The largest known specimen measured about 7 meters (23 ft) in length, its skull was 590 millimeters (1.94 ft) long, and it weighed about 400 kilograms (880 lb). The smaller holotype specimen was about 6.03 meters (19.8 ft) long, with a hip height of about 1.36 meters (4.5 ft), its skull was 523 millimeters (1.716 ft) long, and it weighed about 283 kilograms (624 lb).[4][6] A resting trace of a large theropod that may be Dilophosaurus or a similar theropod has markings around the belly and feet that have been interpreted as feather impressions by some researchers. Others have concluded that the markings are sedimentological artifacts, while noting that this interpretation does not rule out that the track maker bore feathers.[7][8][9]

Dilophosaurus had 9 cervical (neck) vertebrae, 5 pectoral vertebrae (the vertebrae that transition between those of the neck and the back), 10 dorsal (back) vertebrae, and 45 caudal (tail) vertebrae. It had a long neck, which was probably flexed nearly 90° by the skull and by the shoulder, thereby holding the skull in a horizontal posture. The cervical vertebrae were unusually light; their centra (the "bodies" of the vertebrae) were hollowed out by pleurocoels (depressions on the sides) and centrocoels (cavities on the inside). The arches of the cervical vertebrae also had chonoses, conical recesses so large that the bones separating them were sometimes paper-thin. The centra were plano-concave, flat at the font and cupped (or concave) at the back. This indicates that the neck was flexible, though it had long, overlapping cervical ribs, which were fused to the centra. The cervical ribs were slender, and may therefore have bent easily. The atlas bone (the first cervical vertebra which attaches to the skull) had a small, cubic centrum, and had a concavity at the front where it formed a cup for the occipital condyle (protuberance which connects with the atlas vertebra) at the back of the skull. The axis bone (the second cervical vertebra) had a heavy spine, and its postzygapophyses (articular processes) were met by long prezygapophyses that curved upwards from the third cervical vertebra. The centra and spines of the cervical vertebrae were long and low, and the spines had caps which gave the appearance of a Maltese cross when seen from above. The neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae were also low and expanded front and back, which formed strong attachments for ligaments. There were four sacral vertebrae (dorsal vertebrae between the hips), which occupied the length of the ilium blade, and these did not appear to be fused. The centra of the caudal vertebrae were very consistent in length, but their diameter became smaller towards the back, and they went from elliptical to circular in cross-section.[2]

The scapulae (shoulder blades) were moderate in length, wide (particularly the upper part), and were concave on their inner sides to follow the body's curvature. The coracoids were elliptical, and not fused to the scapulae. The arms were powerful, and had deep pits and stout processes for attachment of muscles and ligaments. The humerus (upper arm bone) was large and slender, with stout epipodials, and the ulna (lower arm bone) was stout and straight, with a stout olecranon. The hands had four fingers; the first was shorter but stronger than the following two fingers, with a large claw, and the two following fingers were longer and more slender, with smaller claws. The third finger was reduced, and the fourth was vestigial (was retained, but without function). The crest of the ilium was highest over the peduncle, and its outer side was concave. The foot of the pubic bone was only slightly expanded, whereas the lower end was much more expanded on the ischium, which also had a very thin shaft. The hind-legs were large, with a slighter longer femur (thigh bone) than tibia (lower leg bone), the opposite of for example Coelophysis. The femur was massive, its shaft was sigmoid-shaped, and its greater trochanter was centered on the shaft. The tibia had a developed tuberosity and was expanded at the lower end. The astragalus bone (ankle bone) was separated from the tibia and the calcaneum, and formed half of the socket for the fibula. It had long, stout feet with three well-developed toes that bore large claws. The third toe was the stoutest, and the smaller first toe (the hallux) was kept off the ground.[2][10]

Skull

The skull of Dilophosaurus was large in proportion to the skeleton, yet delicate. The snout was narrow in front view, and narrowing towards the rounded top. The premaxilla (front bone of the upper jaw) was long and low when seen from the side, and its outer surface became less convex from snout to naris (bony nostril). The nostrils were placed further back than in most other theropods. The premaxilla was weakly attached to the maxilla (the following bone of the upper jaw), only connecting at the middle of the palate, with no connection art the side. Hindwards and below, the premaxilla formed a wall for a gap between itself and the maxilla, called the subnarial gap (also called a "kink" or "notch"). Within the gap was a deep excavation behind the toothrow of the premaxilla, called the subnarial pit, which was walled by a downwards keel of the premaxilla. The outer surface of the premaxilla was covered in foramina (openings) of varying sizes. The nasal process (backwards projection from the premaxilla) was long and low, and formed most of the upper border of the elongated naris. It had a dip towards the font, which made the area by its base concave in profile. Seen from below, the premaxilla had an oval area which contained alveoli (tooth sockets). The maxilla was shallow, and was depressed around the antorbital fenestra (a large opening in front of the eye), forming a recess that was rounded towards the front, and smoother than the rest of the maxilla. A foramen called the preantorbital fenestra opened into this recess at the front bend. Large foramina ran on the side of the maxilla, above the alveoli. A deep nutrient groove ran backwards from the subnarial pit along the base of the interdental plates (or rugosae) of the maxilla.[2][11][4]

Dilophosaurus bore two high and thin crests longitudinally on the skull roof, formed by the nasal and lacrimal bones. The paired crests extended upwards and gave the appearance of a cassowary with two crests. Each crest also had a finger-like backwards projection. The upper surface of the nasal bone between the crests was concave, and the nasal part of the crest overlapped the lacrimal part. As only one specimen preserves the shape of the crests, it is unknown if they differed in other individuals. The lacrimal bone had a thickened upper rim, where it formed the upper border at the back of the antorbital fenestra. The prefrontal bone formed the roof of the orbit (eye socket), and had an L-shaped bar that made part of the upper surface of the orbit concave. The orbit was oval, and narrow towards the bottom. The jugal bone had two upwards pointing processes, the first of which formed part of the lower margin of the antorbital fenestra, and part of the lower margin of the orbit. A projection from the quadrate bone into the lateral temporal fenestra (opening behind the eye) gave this a reniform (kidney-shaped) outline. The foramen magnum (the large opening at the back of the braincase) was about half the breadth of the occipital condyle, which was itself cordiform (heart-shaped), and had a short neck and a groove on the side.[2][12][11]

The mandible was slender and delicate at the front, but the articular region (where it connected with the skull) was massive, and the mandible was deep around the mandibular fenestra (an opening on its side). The retroarticular process of the mandible (a backwards projection) was long, the surangular shelf was strongly horizontal. The dentary bone (the front part of the mandible where most of the teeth there attached) had an up-curved rather than pointed chin. The chin had a large foramen at the tip, and a row of small foramina ran in rough parallel with the upper edge of the dentary. On the inner side, the mandibular symphysis (where the two halves of the lower jaw connected) was flat and smooth, and showed no sign of being fused with its opposite half. A Meckelian foramen ran along the outer side of the dentary.[2]

Dilophosaurus had 4 teeth in each premaxilla, 12 in each maxilla, and 17 in each dentary. The teeth were generally long, thin, and recurved, with relatively small bases. They were compressed sideways, oval in cross-section at the base, lenticular (lens-shaped) above, and slightly concave on their outer and inner sides. The teeth of the dentary were much smaller than those of the maxilla. The teeth had serrations on the front and back edges, which were offset by vertical grooves, and were smaller at the front. There were 31 to 41 serrations on the front edges, and 29 to 33 on the back. The teeth were covered in a thin layer of enamel, 0.1 to 0.15 millimeters (0.0039 to 0.0059 in), which extended far towards their bases. The alveoli were elliptical to almost circular, and all were larger than the bases of the teeth they contained, which may therefore have been loosely held in the jaws. Though the number of alveoli in the dentary indicates the teeth were very crowded, they were rather far apart, due to the larger size of their alveoli. The jaws contained replacement teeth at various stages of eruption. The interdental plates between the teeth were very low.[2][13]

History of discovery

In the summer of 1942, the American paleontologist Charles L. Camp led a field party from the University of California Museum of Paleontology in search of fossil vertebrates in the Navajo County of Northern Arizona. Word of this was spread among the native Americans there, and the Navajo Jesse Williams brought three members of the expedition to some fossil bones he had discovered in 1940. The area was part of the Kayenta Formation, about 32 kilometers (20 mi) north of Cameron near Tuba City in the Navajo Indian Reservation. Three dinosaur skeletons were found arranged in a triangle, about 9.1 meters (30 ft) long at one side, in purplish shale. The first was nearly complete, and lacked only the front of the skull, parts of the pelvis, and some vertebrae, the second was very eroded, and included the front of the skull, lower jaws, some vertebrae, limb bones, and an articulated hand, and the third was so eroded that it consisted only of vertebra fragments. The first, good skeleton was encased in a block of plaster after ten days of work and loaded onto a truck, the second skeleton was easily collected as it was almost entirely weathered out of the ground, but the third skeleton was almost gone.[14][2][15]

The nearly complete first specimen was cleaned and mounted at the UCMP under supervision of the American paleontologist Wann Langston Jr., a process that took three men two years. The skeleton was wall mounted in bas relief, with the tail curved upwards, the neck straightened, and the left leg moved up for visibility, but the rest of the skeleton was kept in the position of burial. As the skull was crushed, it was reconstructed based on the back of the skull of the first specimen and the front of the second. The pelvis was reconstructed after that of Allosaurus, and the feet were also reconstructed. At the time, it was one of the best preserved skeletons of a theropod dinosaur, though incomplete. In 1954, the American paleontologist Samuel P. Welles, who was part of the group that excavated the skeletons, preliminarily described and named this dinosaur as a new species in the existing genus Megalosaurus; M. wetherilli. The nearly complete specimen (catalogued as UCMP 37302) became the holotype, and the second specimen (UCMP 37303) was included in the hypodigm (the sample that defines a taxon) of the species. The specific name honored John Wetherill, a Navajo councilor who Welles described as an "explorer, friend of scientists, and trusted trader". Wetherill's nephew, Milton, had first informed the expedition of the fossils. Welles placed the new species in Megalosaurus due to the similar limb proportions of it and M. bucklandii, and because he did not find great differences between them. At the time, Megalosaurus was used as a "wastebasket taxon", wherein many species of theropod were placed, regardless of their age or locality.[14][2][3]

Welles returned to Tuba City in 1964 to determine the age of the Kayenta Formation (it had been suggested to be Late Triassic in age, whereas Welles thought it was Early to Middle Jurassic), and discovered another skeleton about 402.3 kilometers (250.0 mi) south of where the 1942 specimens had been found. The nearly complete specimen (catalogued as UCMP 77270) was collected with the help of William Breed of the Museum of Northern Arizona and others. During preparation of this specimen, it became clear that it was a larger individual of M. wetherilli, and that it would have had two crests on the top of its skull. Being a thin plate of bone, one crest was originally thought to be part of the missing left side of the skull which had been pulled out of its position by a scavenger. When it became apparent it was a crest, it was also realized that there would have been a corresponding crest on the left side, since the right crest was right of the midline, and was concave along its middle length. This discovery led to reexamination of the holotype specimen, which was found to have bases of two thin, upwards extended bones, which were crushed together. These also represented crests, but it had formerly been assumed they were part of a misplaced cheek bone. It was also concluded that the two 1942 specimens were juveniles, while the 1964 specimen was an adult, about one third larger than the others.[2][11][16]