Diabetic nephropathy: Difference between revisions

m cleanup |

consistent citation formatting and templated citations |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

<!-- Definition and symptoms --> |

||

'''Diabetic nephropathy (DN)''', also known as '''diabetic kidney disease''',<ref>{{cite book | title = Nutrition Therapy for Chronic Kidney Disease | chapter = Diabetes Management | |

'''Diabetic nephropathy (DN)''', also known as '''diabetic kidney disease''',<ref>{{cite book | title = Nutrition Therapy for Chronic Kidney Disease | chapter = Diabetes Management | vauthors = Kittell F | veditors = Thomas LK, Othersen JB | year = 2012 | publisher = CRC Press | page = 198 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=DreAtq_hKmcC&pg=PA198}}</ref> is the chronic loss of [[kidney function]] occurring in those with [[diabetes mellitus]]. [[Proteinuria|Protein loss in the urine]] due to damage to the [[glomerulus|glomeruli]] may become massive, and cause a low [[serum albumin]] with resulting [[Anasarca|generalized body swelling (edema)]] and result in the [[nephrotic syndrome]]. Likewise, the estimated [[glomerular filtration rate]] (eGFR) may progressively fall from a normal of over 90 ml/min/1.73m<sup>2</sup></small> to less than 15, at which point the patient is said to have [[end-stage kidney disease]] (ESKD).<ref>{{cite book | first1 = Dan | last1 = Longo | first2 = Anthony | last2 = Fauci | first3 = Dennis | last3= Kasper | first4 = Stephen | last4 = Hauser | first5 = J. | last5 = Jameson | first6 = Joseph | last6 = Loscalzo | name-list-format = vanc | title = Harrison's manual of medicine|date=2013|publisher=McGraw-Hill Medical|location=New York|isbn=978-0-07-174519-2|edition=18th | page = 2982 }}</ref> It usually is slowly progressive over years.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Tuttle K, Weiss NS, de Boer IH | title = Clinical Manifestations of Kidney Disease Among US Adults With Diabetes, 1988-2014 | journal = JAMA | volume = 316 | issue = 6 | pages = 602–10 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 27532915 | doi = 10.1001/jama.2016.10924 }}</ref> |

||

<!-- Cause and Pathophysiology --> |

<!-- Cause and Pathophysiology --> |

||

Pathophysiologic abnormalities in DN begin with long-standing poorly controlled blood glucose levels. This is followed by multiple changes in the filtration units of the kidneys, the [[nephron]]s. (There are normally about 750,000-1.5 million nephrons in each adult kidney).<ref> |

Pathophysiologic abnormalities in DN begin with long-standing poorly controlled blood glucose levels. This is followed by multiple changes in the filtration units of the kidneys, the [[nephron]]s. (There are normally about 750,000-1.5 million nephrons in each adult kidney).<ref>{{cite book | first1 = John | last1 = Hall | first2 = Arthur | last2 = Guyton | name-list-format = vanc |title= Textbook of Medical Physiology | date = 2005 | publisher = W.B. Saunders | location =Philadelphia | isbn = 978-0-7216-0240-0 | edition = 11th | page = 310 }}</ref> Initially, there is constriction of the [[efferent arterioles]] and dilation of [[afferent arterioles]], with resulting glomerular capillary hypertension and hyperfiltration; this gradually changes to hypofiltration over time.<ref>{{cite web | title = diabetic nephropathy | url = http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/diabetic+nephropathy | access-date = 2015-06-27 }}</ref> Concurrently, there are changes within the glomerulus itself: these include a thickening of the [[basement membrane]], a widening of the slit membranes of the [[podocytes]], an increase in the number of mesangial cells, and an increase in mesangial matrix. This matrix invades the glomerular capillaries and produces deposits called Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules. The mesangial cells and matrix can progressively expand and consume the entire glomerulus, shutting off filtration.<ref name="Schlöndorff_2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schlöndorff D, Banas B | title = The mesangial cell revisited: no cell is an island | journal = Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN | volume = 20 | issue = 6 | pages = 1179–87 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19470685 | doi = 10.1681/ASN.2008050549 }}</ref> |

||

<!-- Prevention and Treatment --> |

<!-- Prevention and Treatment --> |

||

The status of DN may be monitored by measuring two values: the amount of protein in the urine - [[proteinuria]]; and a blood test called the serum [[creatinine]]. The amount of the proteinuria reflects the degree of damage to any still-functioning glomeruli. The value of the [[serum creatinine]] can be used to calculate the [[estimated glomerular filtration rate]] (eGFR), which reflects the percentage of glomeruli which are no longer filtering the blood. {{citation needed|date=December 2017}} Treatment with an [[angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor]] (ACEI) or [[angiotensin receptor blocker]] (ARB), which dilates the [[arteriole]] exiting the glomerulus, thus reducing the [[blood pressure]] within the glomerular capillaries, which may slow (but not stop) progression of the disease. Three classes of diabetes medications - [[GLP-1 agonist]]s, [[DPP-4 inhibitor]]s, and [[SGLT2 inhibitor]]s - are also thought to slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.<ref>{{cite journal | |

The status of DN may be monitored by measuring two values: the amount of protein in the urine - [[proteinuria]]; and a blood test called the serum [[creatinine]]. The amount of the proteinuria reflects the degree of damage to any still-functioning glomeruli. The value of the [[serum creatinine]] can be used to calculate the [[estimated glomerular filtration rate]] (eGFR), which reflects the percentage of glomeruli which are no longer filtering the blood. {{citation needed|date=December 2017}} Treatment with an [[angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor]] (ACEI) or [[angiotensin receptor blocker]] (ARB), which dilates the [[arteriole]] exiting the glomerulus, thus reducing the [[blood pressure]] within the glomerular capillaries, which may slow (but not stop) progression of the disease. Three classes of diabetes medications - [[GLP-1 agonist]]s, [[DPP-4 inhibitor]]s, and [[SGLT2 inhibitor]]s - are also thought to slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = de Boer IH | title = A New Chapter for Diabetic Kidney Disease | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 377 | issue = 9 | pages = 885–887 | date = August 2017 | pmid = 28854097 | doi = 10.1056/nejme1708949 }}</ref> |

||

<!-- Epidemiology --> |

<!-- Epidemiology --> |

||

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of ESKD and is a serious complication and affects around one-quarter of adult diabetics in the United States.<ref name="Fernandez2014">{{cite journal |

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of ESKD and is a serious complication and affects around one-quarter of adult diabetics in the United States.<ref name="Fernandez2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mora-Fernández C, Domínguez-Pimentel V, de Fuentes MM, Górriz JL, Martínez-Castelao A, Navarro-González JF | title = Diabetic kidney disease: from physiology to therapeutics | journal = The Journal of Physiology | volume = 592 | issue = 18 | pages = 3997–4012 | date = September 2014 | pmid = 24907306 | pmc = 4198010 | doi = 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.272328 }}</ref><ref name="Ding2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ding Y, Choi ME | title = Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy | journal = The Journal of Endocrinology | volume = 224 | issue = 1 | pages = R15-30 | date = January 2015 | pmid = 25349246 | pmc = 4238413 | doi = 10.1530/JOE-14-0437 }}</ref> Affected individuals with end-stage kidney disease often require [[hemodialysis]] and eventually [[kidney transplantation]] to replace the failed kidney function.<ref name="ReferenceB">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lizicarova D, Krahulec B, Hirnerova E, Gaspar L, Celecova Z | title = Risk factors in diabetic nephropathy progression at present | journal = Bratislavske Lekarske Listy | volume = 115 | issue = 8 | pages = 517–21 | year = 2014 | pmid = 25246291 | doi = 10.4149/BLL_2014_101 }}</ref> Diabetic nephropathy is associated with an increased [[Mortality rate|risk of death]] in general, particularly from [[cardiovascular disease]].<ref name="Fernandez2014"/><ref name="Pálsson R 2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pálsson R, Patel UD | title = Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease | journal = Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease | volume = 21 | issue = 3 | pages = 273–80 | date = May 2014 | pmid = 24780455 | pmc = 4045477 | doi = 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.003 }}</ref> |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

==Risk factors== |

==Risk factors== |

||

The incidence of diabetic nephropathy is higher in diabetics with one or more of the following conditions:<ref name="nih">{{Cite web|title = Diabetes and kidney disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia|url = https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000494.htm|website = www.nlm.nih.gov| |

The incidence of diabetic nephropathy is higher in diabetics with one or more of the following conditions:<ref name="nih">{{Cite web|title = Diabetes and kidney disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia|url = https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000494.htm|website = www.nlm.nih.gov|access-date = 2015-06-27}}</ref> |

||

* Poor control of blood glucose |

* Poor control of blood glucose |

||

* Uncontrolled [[Hypertension|high blood pressure]] |

* Uncontrolled [[Hypertension|high blood pressure]] |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

==Pathophysiology== |

==Pathophysiology== |

||

[[File:Physiology of Nephron.png|250px|thumb|right|Diagram showing the basic outline of nephron structure and function: diabetic nephropathy is associated with changes in the afferent and efferent arterioles, causing capillary hypertension; and damage to the glomerular capillaries of multiple causes, including mesangial matrix deposition]] |

[[File:Physiology of Nephron.png|250px|thumb|right|Diagram showing the basic outline of nephron structure and function: diabetic nephropathy is associated with changes in the afferent and efferent arterioles, causing capillary hypertension; and damage to the glomerular capillaries of multiple causes, including mesangial matrix deposition]] |

||

The pathophysiology of the glomerulus in DN can best be understood by considering the three involved cells as a unit: the [[endothelial cell]], the [[podocyte]], and the [[mesangial cell]]. These cells are in physical contact with one another at various locations within the glomerulus; they also communicate with one another chemically at a distance. All three cells are abnormal in DN.<ref name=" |

The pathophysiology of the glomerulus in DN can best be understood by considering the three involved cells as a unit: the [[endothelial cell]], the [[podocyte]], and the [[mesangial cell]]. These cells are in physical contact with one another at various locations within the glomerulus; they also communicate with one another chemically at a distance. All three cells are abnormal in DN.<ref name="Schlöndorff_2009"/> |

||

[[Diabetes]] causes a number of changes to the body's [[metabolism]] and [[Hemodynamics|blood circulation]], which likely combine to produce excess [[reactive oxygen species]] (chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen). These changes damage the kidney's [[Glomerulus (kidney)|glomeruli]] (networks of [[Capillary|tiny blood vessels]]), which leads to the hallmark feature of [[albumin]] in the urine (called [[albuminuria]]).<ref>{{ |

[[Diabetes]] causes a number of changes to the body's [[metabolism]] and [[Hemodynamics|blood circulation]], which likely combine to produce excess [[reactive oxygen species]] (chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen). These changes damage the kidney's [[Glomerulus (kidney)|glomeruli]] (networks of [[Capillary|tiny blood vessels]]), which leads to the hallmark feature of [[albumin]] in the urine (called [[albuminuria]]).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cao Z, Cooper ME | title = Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy | journal = Journal of Diabetes Investigation | volume = 2 | issue = 4 | pages = 243–7 | date = August 2011 | pmid = 24843491 | pmc = 4014960 | doi = 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00131.x }}</ref> As diabetic nephropathy progresses, a structure in the glomeruli known as the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is increasingly damaged.<ref name="Fernandez2014"/> This barrier is composed of three layers including the fenestrated [[endothelium]], the [[glomerular basement membrane]], and the [[epithelium|epithelial]] [[podocyte]]s.<ref name="Fernandez2014"/> The GFB is responsible for the highly selective filtration of blood entering the kidney's glomeruli and normally only allows the passage of water, small molecules, and very small proteins (albumin does not pass through the intact GFB).<ref name="Fernandez2014"/> Damage to the glomerular basement membrane allows proteins in the blood to leak through, leading to proteinuria. Deposition of abnormally large amounts of mesangial matrix causes [[Periodic acid–Schiff stain|periodic-acid schiff]] positive nodules called Kimmelstiel–Wilson nodules.{{citation needed|date=October 2016}} |

||

[[Hyperglycemia|High blood sugar]], which leads to formation of [[advanced glycation end product]]s; and [[cytokine]]s have also been implicated as mechanisms for the development of diabetic nephropathy.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Diabetic Nephropathy: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology|url = http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/238946-overview#a4|date = 2015-06-20}}</ref> |

[[Hyperglycemia|High blood sugar]], which leads to formation of [[advanced glycation end product]]s; and [[cytokine]]s have also been implicated as mechanisms for the development of diabetic nephropathy.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Diabetic Nephropathy: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology|url = http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/238946-overview#a4|date = 2015-06-20}}</ref> |

||

Another relevant factor is diabetes-induced hypoxia, which is an aggravating factor, since it increases interstitial fibrosis, partly by the induction of the synthesis of [[Transforming growth factor beta|TGF-β]] and [[Vascular endothelial growth factor|vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)]], which is mediated by hypoxia-inducing factor-1.<ref name="blaz">{{ |

Another relevant factor is diabetes-induced hypoxia, which is an aggravating factor, since it increases interstitial fibrosis, partly by the induction of the synthesis of [[Transforming growth factor beta|TGF-β]] and [[Vascular endothelial growth factor|vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)]], which is mediated by hypoxia-inducing factor-1.<ref name="blaz">{{cite journal | vauthors = Blázquez-Medela AM, López-Novoa JM, Martínez-Salgado C | title = Mechanisms involved in the genesis of diabetic nephropathy | journal = Current Diabetes Reviews | volume = 6 | issue = 2 | pages = 68–87 | date = March 2010 | pmid = 20041836 | doi = 10.2174/157339910790909422 }}</ref> Hypoxia can activate fibroblasts and alter extracellular matrix metabolism of resident renal cells, leading to eventual fibrogenesis and even mild hypoxia can induce transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells into myofibroblasts, leading to a vicious cycle exists with hypoxia promoting interstitial fibrosis and increased matrix deposition; in turn further impairing peritubular blood flow and oxygen supply.<ref name=blaz/> |

||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

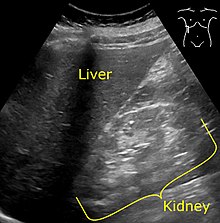

[[File:Ultrasonography of kidney with diabetic nephropathy - annotated.jpg|thumb|left|[[Medical ultrasonography|Ultrasonography]] showing [[Echogenicity|hyperechogenicity]] of the [[renal cortex]], visualized in the image as brighter than the liver.]] |

[[File:Ultrasonography of kidney with diabetic nephropathy - annotated.jpg|thumb|left|[[Medical ultrasonography|Ultrasonography]] showing [[Echogenicity|hyperechogenicity]] of the [[renal cortex]], visualized in the image as brighter than the liver.]] |

||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:5px" |

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:5px" |

||

Diagnosis is based on the measurement of abnormal levels of urinary albumin in a diabetic<ref name="lewis2014">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lewis G, Maxwell AP |title=Risk factor control is key in diabetic nephropathy |journal=Practitioner |volume=258 |issue=1768 |pages=13–7, 2 | |

Diagnosis is based on the measurement of abnormal levels of urinary albumin in a diabetic<ref name="lewis2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lewis G, Maxwell AP | title = Risk factor control is key in diabetic nephropathy | journal = The Practitioner | volume = 258 | issue = 1768 | pages = 13–7, 2 | date = February 2014 | pmid = 24689163 }}</ref> coupled with exclusion of other causes of albuminuria. |

||

Albumin measurements are defined as follows:<ref>{{Cite web|title = CDC - Chronic Kidney Disease - Glossary|url = http://nccd.cdc.gov/ckd/help.aspx?section=G| |

Albumin measurements are defined as follows:<ref>{{Cite web|title = CDC - Chronic Kidney Disease - Glossary|url = http://nccd.cdc.gov/ckd/help.aspx?section=G|access-date = 2015-07-02}}</ref> |

||

:::::::::::* Normal [[albuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion <30 mg/24h; |

:::::::::::* Normal [[albuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion <30 mg/24h; |

||

:::::::::::* [[Microalbuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion in the range of 30–299 mg/24h; |

:::::::::::* [[Microalbuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion in the range of 30–299 mg/24h; |

||

:::::::::::* [[Macroalbuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion ≥300 mg/24h. |

:::::::::::* [[Macroalbuminuria]]: urinary albumin excretion ≥300 mg/24h. |

||

It is recommended that diabetics have their albumin levels checked annually, beginning immediately after a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and five years after a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.<ref name="lewis2014" /><ref>{{ |

It is recommended that diabetics have their albumin levels checked annually, beginning immediately after a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and five years after a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.<ref name="lewis2014" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Koroshi A | title = Microalbuminuria, is it so important? | journal = Hippokratia | volume = 11 | issue = 3 | pages = 105–7 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 19582202 | pmc = 2658722 }}</ref> |

||

[[Medical imaging]] of the kidneys, generally by [[medical ultrasonography|ultrasonography]], is recommended as part of a [[differential diagnosis]] if there is suspicion of [[urinary tract obstruction]], [[urinary tract infection]], or [[kidney stone]]s or [[polycystic kidney disease]].<ref name="Grossde Azevedo2004">{{cite journal| |

[[Medical imaging]] of the kidneys, generally by [[medical ultrasonography|ultrasonography]], is recommended as part of a [[differential diagnosis]] if there is suspicion of [[urinary tract obstruction]], [[urinary tract infection]], or [[kidney stone]]s or [[polycystic kidney disease]].<ref name="Grossde Azevedo2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T | title = Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment | journal = Diabetes Care | volume = 28 | issue = 1 | pages = 164–76 | date = January 2005 | pmid = 15616252 | doi = 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164 }}</ref> |

||

===Staging=== |

===Staging=== |

||

!CKD Stage<ref name="pmid22439155">{{cite book | vauthors = Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, Sadiq S, Lankireddy S, Kane RL, Wilt TJ | display-authors = 6 | title = Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 1–3: Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment [Internet] | pmid = 22439155 | doi = | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK84558/ }}</ref> |

|||

!CKD Stage<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Introduction|url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK84558/|date = 2012|language = en|first = Howard A.|last = Fink|first2 = Areef|last2 = Ishani|first3 = Brent C.|last3 = Taylor|first4 = Nancy L.|last4 = Greer|first5 = Roderick|last5 = MacDonald|first6 = Dominic|last6 = Rossini|first7 = Sameea|last7 = Sadiq|first8 = Srilakshmi|last8 = Lankireddy|first9 = Robert L.|last9 = Kane}}</ref> |

|||

!eGFR level <small>(mL/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup>)</small> |

!eGFR level <small>(mL/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup>)</small> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 86: | Line 87: | ||

|style="text-align:center"|< 15 |

|style="text-align:center"|< 15 |

||

|} |

|} |

||

To stage the degree of damage in this (and any) kidney disease, the serum creatinine is determined and used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate ([[Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate|eGFR]]). Normal eGFR is equal to or greater than 90ml/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup>.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Glomerular filtration rate: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia|url = https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/007305.htm|website = www.nlm.nih.gov| |

To stage the degree of damage in this (and any) kidney disease, the serum creatinine is determined and used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate ([[Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate|eGFR]]). Normal eGFR is equal to or greater than 90ml/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup>.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Glomerular filtration rate: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia|url = https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/007305.htm|website = www.nlm.nih.gov|access-date = 2015-07-02}}</ref> |

||

== Treatment == |

== Treatment == |

||

The goals of treatment are to slow the progression of kidney damage and control related complications. The main treatment, once proteinuria is established, is [[ACE inhibitor]] medications, which usually reduce proteinuria levels and slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.<ref name="ace">{{ |

The goals of treatment are to slow the progression of kidney damage and control related complications. The main treatment, once proteinuria is established, is [[ACE inhibitor]] medications, which usually reduce proteinuria levels and slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.<ref name="ace">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lim AK | title = Diabetic nephropathy - complications and treatment | journal = International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease | volume = 7 | pages = 361–81 | date = 2014 | pmid = 25342915 | pmc = 4206379 | doi = 10.2147/IJNRD.S40172 }}</ref> Other issues that are important in the management of this condition include control of [[high blood pressure]] and [[blood sugar]] levels (see [[diabetes management]]), as well as the reduction of dietary salt intake.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Diabetic Nephropathy Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Glycemic Control, Management of Hypertension|url = http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/238946-treatment|date = 2015-06-20}}</ref> |

||

==Prognosis== |

==Prognosis== |

||

Diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes can be more difficult to predict because the onset of diabetes is not usually well established. Without intervention, 20-40 percent of patients with type 2 diabetes/microalbuminuria, will evolve to macroalbuminuria.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Clinical Evidence Handbook: Diabetic Nephropathy: Preventing Progression - American Family Physician|url = http://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0315/p732.html|website = www.aafp.org| |

Diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes can be more difficult to predict because the onset of diabetes is not usually well established. Without intervention, 20-40 percent of patients with type 2 diabetes/microalbuminuria, will evolve to macroalbuminuria.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Clinical Evidence Handbook: Diabetic Nephropathy: Preventing Progression - American Family Physician|url = http://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0315/p732.html|website = www.aafp.org|access-date = 2015-06-27|first = Michael|last = Shlipak | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

||

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of [[end-stage kidney disease]],<ref name="Fernandez2014"/><ref name="Ding2015"/> which may require [[hemodialysis]] or even [[kidney transplantation]].<ref name="ReferenceB"/> It is associated with an increased [[Mortality rate|risk of death]] in general, particularly from [[cardiovascular disease]].<ref name="Fernandez2014"/><ref name="Pálsson R 2014"/> |

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of [[end-stage kidney disease]],<ref name="Fernandez2014"/><ref name="Ding2015"/> which may require [[hemodialysis]] or even [[kidney transplantation]].<ref name="ReferenceB"/> It is associated with an increased [[Mortality rate|risk of death]] in general, particularly from [[cardiovascular disease]].<ref name="Fernandez2014"/><ref name="Pálsson R 2014"/> |

||

== Epidemiology == |

== Epidemiology == |

||

In the U.S., diabetic nephropathy affected an estimated 6.9 million people during 2005–2008.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Diabetes and Kidney Disease|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=wsYkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA10&dq=Diabetic+nephropathy+epidemiology |

In the U.S., diabetic nephropathy affected an estimated 6.9 million people during 2005–2008.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Diabetes and Kidney Disease|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=wsYkBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA10&dq=Diabetic+nephropathy+epidemiology |publisher = Springer|date = 2014-01-01|isbn = 9781493907939 |first = Edgar V.|last = Lerma | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> The number of people with diabetes and consequently diabetic nephropathy is expected to rise substantially by the year 2050.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Diabetes and the Kidney|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=XZk7AQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1&dq=Diabetic+nephropathy+epidemiology |publisher = Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers|date = 2011-06-08|isbn = 9783805597432 | vauthors = Lai KN, Tang SC }}</ref> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 104: | Line 105: | ||

* [[Nephrology]] |

* [[Nephrology]] |

||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|32em}} |

||

==Further reading== |

== Further reading == |

||

{{refbegin|32em}} |

|||

*{{Cite web|title = Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockers on renal outcomes and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy: an updated meta-analysis|url = http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/ShowRecord.asp?AccessionNumber=12009100199#.VZXF8TfbJpg|website = www.crd.york.ac.uk| |

*{{Cite web|title = Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockers on renal outcomes and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy: an updated meta-analysis|url = http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/ShowRecord.asp?AccessionNumber=12009100199#.VZXF8TfbJpg|website = www.crd.york.ac.uk|access-date = 2015-07-02}} |

||

*{{Cite journal|title = Diabetic Nephropathy: Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment|url = http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/28/1/164|journal = Diabetes Care|date = 2005|issn = 0149-5992|pmid = 15616252|pages = 164–176|volume = 28|issue = 1|doi = 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164|language = en|first = Jorge L.|last = Gross|first2 = Mirela J. de|last2 = Azevedo|first3 = Sandra P.|last3 = Silveiro|first4 = Luís Henrique|last4 = Canani|first5 = Maria Luiza|last5 = Caramori|first6 = Themis|last6 = Zelmanovitz}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T | title = Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment | journal = Diabetes Care | volume = 28 | issue = 1 | pages = 164–76 | date = January 2005 | pmid = 15616252 | doi = 10.2337/diacare.28.1.164 }} |

|||

*{{cite journal| |

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Tziomalos K, Athyros VG | title = Diabetic Nephropathy: New Risk Factors and Improvements in Diagnosis | journal = The Review of Diabetic Studies | volume = 12 | issue = 1-2 | pages = 110–8 | year = 2015 | pmid = 26676664 | pmc = 5397986 | doi = 10.1900/RDS.2015.12.110 }} |

||

*{{cite journal| |

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Kume S, Koya D, Uzu T, Maegawa H | title = Role of nutrient-sensing signals in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy | journal = BioMed Research International | volume = 2014 | pages = 315494 | date = 2014 | pmid = 25126552 | pmc = 4122096 | doi = 10.1155/2014/315494 }} |

||

*{{cite journal| |

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Doshi SM, Friedman AN | title = Diagnosis and Management of Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease | journal = Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology | volume = 12 | issue = 8 | pages = 1366–1373 | date = August 2017 | pmid = 28280116 | doi = 10.2215/CJN.11111016 }} |

||

{{refend}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

Revision as of 05:31, 19 May 2018

| Diabetic nephropathy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Two glomeruli in diabetic nephropathy: the acellular light purple areas within the capillary tufts are the destructive mesangial matrix deposits. | |

| Specialty | Nephrology, endocrinology |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, Unstable blood glucose[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Abnormal levels of urinary albumin[2] |

| Treatment | ACE inhibitors[3] |

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), also known as diabetic kidney disease,[4] is the chronic loss of kidney function occurring in those with diabetes mellitus. Protein loss in the urine due to damage to the glomeruli may become massive, and cause a low serum albumin with resulting generalized body swelling (edema) and result in the nephrotic syndrome. Likewise, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) may progressively fall from a normal of over 90 ml/min/1.73m2 to less than 15, at which point the patient is said to have end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).[5] It usually is slowly progressive over years.[6]

Pathophysiologic abnormalities in DN begin with long-standing poorly controlled blood glucose levels. This is followed by multiple changes in the filtration units of the kidneys, the nephrons. (There are normally about 750,000-1.5 million nephrons in each adult kidney).[7] Initially, there is constriction of the efferent arterioles and dilation of afferent arterioles, with resulting glomerular capillary hypertension and hyperfiltration; this gradually changes to hypofiltration over time.[8] Concurrently, there are changes within the glomerulus itself: these include a thickening of the basement membrane, a widening of the slit membranes of the podocytes, an increase in the number of mesangial cells, and an increase in mesangial matrix. This matrix invades the glomerular capillaries and produces deposits called Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules. The mesangial cells and matrix can progressively expand and consume the entire glomerulus, shutting off filtration.[9]

The status of DN may be monitored by measuring two values: the amount of protein in the urine - proteinuria; and a blood test called the serum creatinine. The amount of the proteinuria reflects the degree of damage to any still-functioning glomeruli. The value of the serum creatinine can be used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), which reflects the percentage of glomeruli which are no longer filtering the blood. [citation needed] Treatment with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), which dilates the arteriole exiting the glomerulus, thus reducing the blood pressure within the glomerular capillaries, which may slow (but not stop) progression of the disease. Three classes of diabetes medications - GLP-1 agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors, and SGLT2 inhibitors - are also thought to slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.[10]

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of ESKD and is a serious complication and affects around one-quarter of adult diabetics in the United States.[11][12] Affected individuals with end-stage kidney disease often require hemodialysis and eventually kidney transplantation to replace the failed kidney function.[13] Diabetic nephropathy is associated with an increased risk of death in general, particularly from cardiovascular disease.[11][14]

Signs and symptoms

The onset of symptoms is 5 to 10 years after the disease begins.[1] A usual first symptom is frequent urination at night: nocturia. Other symptoms include tiredness, headaches, a general feeling of illness, nausea, vomiting, frequent daytime urination, lack of appetite, itchy skin, and leg swelling.[1]

Risk factors

The incidence of diabetic nephropathy is higher in diabetics with one or more of the following conditions:[1]

- Poor control of blood glucose

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus, with onset before age 20

- Past or current cigarette use

- A family history of diabetic nephropathy

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of the glomerulus in DN can best be understood by considering the three involved cells as a unit: the endothelial cell, the podocyte, and the mesangial cell. These cells are in physical contact with one another at various locations within the glomerulus; they also communicate with one another chemically at a distance. All three cells are abnormal in DN.[9]

Diabetes causes a number of changes to the body's metabolism and blood circulation, which likely combine to produce excess reactive oxygen species (chemically reactive molecules containing oxygen). These changes damage the kidney's glomeruli (networks of tiny blood vessels), which leads to the hallmark feature of albumin in the urine (called albuminuria).[15] As diabetic nephropathy progresses, a structure in the glomeruli known as the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is increasingly damaged.[11] This barrier is composed of three layers including the fenestrated endothelium, the glomerular basement membrane, and the epithelial podocytes.[11] The GFB is responsible for the highly selective filtration of blood entering the kidney's glomeruli and normally only allows the passage of water, small molecules, and very small proteins (albumin does not pass through the intact GFB).[11] Damage to the glomerular basement membrane allows proteins in the blood to leak through, leading to proteinuria. Deposition of abnormally large amounts of mesangial matrix causes periodic-acid schiff positive nodules called Kimmelstiel–Wilson nodules.[citation needed]

High blood sugar, which leads to formation of advanced glycation end products; and cytokines have also been implicated as mechanisms for the development of diabetic nephropathy.[16]

Another relevant factor is diabetes-induced hypoxia, which is an aggravating factor, since it increases interstitial fibrosis, partly by the induction of the synthesis of TGF-β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is mediated by hypoxia-inducing factor-1.[17] Hypoxia can activate fibroblasts and alter extracellular matrix metabolism of resident renal cells, leading to eventual fibrogenesis and even mild hypoxia can induce transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells into myofibroblasts, leading to a vicious cycle exists with hypoxia promoting interstitial fibrosis and increased matrix deposition; in turn further impairing peritubular blood flow and oxygen supply.[17]

Diagnosis

- Normal albuminuria: urinary albumin excretion <30 mg/24h;

- Microalbuminuria: urinary albumin excretion in the range of 30–299 mg/24h;

- Macroalbuminuria: urinary albumin excretion ≥300 mg/24h.

Staging

| CKD Stage[21] | eGFR level (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 | ≥ 90 |

| Stage 2 | 60 – 89 |

| Stage 3 | 30 – 59 |

| Stage 4 | 15 – 29 |

| Stage 5 | < 15 |

To stage the degree of damage in this (and any) kidney disease, the serum creatinine is determined and used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Normal eGFR is equal to or greater than 90ml/min/1.73 m2.[22]

Treatment

The goals of treatment are to slow the progression of kidney damage and control related complications. The main treatment, once proteinuria is established, is ACE inhibitor medications, which usually reduce proteinuria levels and slow the progression of diabetic nephropathy.[3] Other issues that are important in the management of this condition include control of high blood pressure and blood sugar levels (see diabetes management), as well as the reduction of dietary salt intake.[23]

Prognosis

Diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes can be more difficult to predict because the onset of diabetes is not usually well established. Without intervention, 20-40 percent of patients with type 2 diabetes/microalbuminuria, will evolve to macroalbuminuria.[24]

Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease,[11][12] which may require hemodialysis or even kidney transplantation.[13] It is associated with an increased risk of death in general, particularly from cardiovascular disease.[11][14]

Epidemiology

In the U.S., diabetic nephropathy affected an estimated 6.9 million people during 2005–2008.[25] The number of people with diabetes and consequently diabetic nephropathy is expected to rise substantially by the year 2050.[26]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Diabetes and kidney disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^ a b c Lewis G, Maxwell AP (February 2014). "Risk factor control is key in diabetic nephropathy". The Practitioner. 258 (1768): 13–7, 2. PMID 24689163.

- ^ a b Lim AK (2014). "Diabetic nephropathy - complications and treatment". International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease. 7: 361–81. doi:10.2147/IJNRD.S40172. PMC 4206379. PMID 25342915.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kittell F (2012). "Diabetes Management". In Thomas LK, Othersen JB (eds.). Nutrition Therapy for Chronic Kidney Disease. CRC Press. p. 198.

- ^ Longo, Dan; Fauci, Anthony; Kasper, Dennis; Hauser, Stephen; Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, Joseph (2013). Harrison's manual of medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 2982. ISBN 978-0-07-174519-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Tuttle K, Weiss NS, de Boer IH (August 2016). "Clinical Manifestations of Kidney Disease Among US Adults With Diabetes, 1988-2014". JAMA. 316 (6): 602–10. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10924. PMID 27532915.

- ^ Hall, John; Guyton, Arthur (2005). Textbook of Medical Physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "diabetic nephropathy". Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ^ a b Schlöndorff D, Banas B (June 2009). "The mesangial cell revisited: no cell is an island". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 20 (6): 1179–87. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008050549. PMID 19470685.

- ^ de Boer IH (August 2017). "A New Chapter for Diabetic Kidney Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (9): 885–887. doi:10.1056/nejme1708949. PMID 28854097.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mora-Fernández C, Domínguez-Pimentel V, de Fuentes MM, Górriz JL, Martínez-Castelao A, Navarro-González JF (September 2014). "Diabetic kidney disease: from physiology to therapeutics". The Journal of Physiology. 592 (18): 3997–4012. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.272328. PMC 4198010. PMID 24907306.

- ^ a b Ding Y, Choi ME (January 2015). "Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy". The Journal of Endocrinology. 224 (1): R15-30. doi:10.1530/JOE-14-0437. PMC 4238413. PMID 25349246.

- ^ a b Lizicarova D, Krahulec B, Hirnerova E, Gaspar L, Celecova Z (2014). "Risk factors in diabetic nephropathy progression at present". Bratislavske Lekarske Listy. 115 (8): 517–21. doi:10.4149/BLL_2014_101. PMID 25246291.

- ^ a b Pálsson R, Patel UD (May 2014). "Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease". Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 21 (3): 273–80. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.003. PMC 4045477. PMID 24780455.

- ^ Cao Z, Cooper ME (August 2011). "Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy". Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2 (4): 243–7. doi:10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00131.x. PMC 4014960. PMID 24843491.

- ^ "Diabetic Nephropathy: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2015-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Blázquez-Medela AM, López-Novoa JM, Martínez-Salgado C (March 2010). "Mechanisms involved in the genesis of diabetic nephropathy". Current Diabetes Reviews. 6 (2): 68–87. doi:10.2174/157339910790909422. PMID 20041836.

- ^ "CDC - Chronic Kidney Disease - Glossary". Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ Koroshi A (July 2007). "Microalbuminuria, is it so important?". Hippokratia. 11 (3): 105–7. PMC 2658722. PMID 19582202.

- ^ Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T (January 2005). "Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment". Diabetes Care. 28 (1): 164–76. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. PMID 15616252.

- ^ Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 1–3: Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment [Internet]. PMID 22439155.

- ^ "Glomerular filtration rate: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ "Diabetic Nephropathy Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Glycemic Control, Management of Hypertension". 2015-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shlipak, Michael. "Clinical Evidence Handbook: Diabetic Nephropathy: Preventing Progression - American Family Physician". www.aafp.org. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Lerma, Edgar V. (2014-01-01). Diabetes and Kidney Disease. Springer. ISBN 9781493907939.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Lai KN, Tang SC (2011-06-08). Diabetes and the Kidney. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. ISBN 9783805597432.

Further reading

- "Effects of renin-angiotensin system blockers on renal outcomes and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetic nephropathy: an updated meta-analysis". www.crd.york.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- Gross JL, de Azevedo MJ, Silveiro SP, Canani LH, Caramori ML, Zelmanovitz T (January 2005). "Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis, prevention, and treatment". Diabetes Care. 28 (1): 164–76. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.1.164. PMID 15616252.

- Tziomalos K, Athyros VG (2015). "Diabetic Nephropathy: New Risk Factors and Improvements in Diagnosis". The Review of Diabetic Studies. 12 (1–2): 110–8. doi:10.1900/RDS.2015.12.110. PMC 5397986. PMID 26676664.

- Kume S, Koya D, Uzu T, Maegawa H (2014). "Role of nutrient-sensing signals in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy". BioMed Research International. 2014: 315494. doi:10.1155/2014/315494. PMC 4122096. PMID 25126552.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Doshi SM, Friedman AN (August 2017). "Diagnosis and Management of Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (8): 1366–1373. doi:10.2215/CJN.11111016. PMID 28280116.

External links

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement