Colloidal gold: Difference between revisions

consistent citation formatting; added missing PMIDs to cites; removed redundant URLs from citations with DOIs |

tweak cites |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Due to their [[Metallic bond#Optical properties|optical]], electronic, and molecular-recognition properties, gold nanoparticles are the subject of substantial research, with many potential or promised applications in a wide variety of areas, including [[electron microscopy]], [[electronics]], [[nanotechnology]], [[materials science]], and [[biomedicine]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yang X, Yang M, Pang B, Vara M, Xia Y | title = Gold Nanomaterials at Work in Biomedicine | journal = Chemical Reviews | volume = 115 | issue = 19 | pages = 10410–88 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26293344 | doi = 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00193 }}</ref><ref name="ref4">Paul Mulvaney, University of Melbourne, ''The beauty and elegance of Nanocrystals'', [http://uninews.unimelb.edu.au/articleid_791.html Use since Roman times] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041028230241/http://uninews.unimelb.edu.au/articleid_791.html |date=2004-10-28 }}</ref><ref name="ref5">C. N. Ramachandra Rao, Giridhar U. Kulkarni, P. John Thomasa, Peter P. Edwards, ''Metal nanoparticles and their assemblies'', Chem. Soc. Rev., '''2000''', 29, 27–35. ([http://pubs.rsc.org/ej/CS/2000/a904518j.pdf on-line here; mentions Cassius and Kunchel])</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dreaden EC, Alkilany AM, Huang X, Murphy CJ, El-Sayed MA | title = The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 41 | issue = 7 | pages = 2740–79 | date = April 2012 | pmid = 22109657 | pmc = 5876014 | doi = 10.1039/c1cs15237h }}</ref> |

Due to their [[Metallic bond#Optical properties|optical]], electronic, and molecular-recognition properties, gold nanoparticles are the subject of substantial research, with many potential or promised applications in a wide variety of areas, including [[electron microscopy]], [[electronics]], [[nanotechnology]], [[materials science]], and [[biomedicine]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yang X, Yang M, Pang B, Vara M, Xia Y | title = Gold Nanomaterials at Work in Biomedicine | journal = Chemical Reviews | volume = 115 | issue = 19 | pages = 10410–88 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26293344 | doi = 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00193 }}</ref><ref name="ref4">Paul Mulvaney, University of Melbourne, ''The beauty and elegance of Nanocrystals'', [http://uninews.unimelb.edu.au/articleid_791.html Use since Roman times] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041028230241/http://uninews.unimelb.edu.au/articleid_791.html |date=2004-10-28 }}</ref><ref name="ref5">C. N. Ramachandra Rao, Giridhar U. Kulkarni, P. John Thomasa, Peter P. Edwards, ''Metal nanoparticles and their assemblies'', Chem. Soc. Rev., '''2000''', 29, 27–35. ([http://pubs.rsc.org/ej/CS/2000/a904518j.pdf on-line here; mentions Cassius and Kunchel])</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dreaden EC, Alkilany AM, Huang X, Murphy CJ, El-Sayed MA | title = The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 41 | issue = 7 | pages = 2740–79 | date = April 2012 | pmid = 22109657 | pmc = 5876014 | doi = 10.1039/c1cs15237h }}</ref> |

||

The properties of colloidal gold nanoparticles, and thus their applications, depend strongly upon their size and shape.<ref>{{cite journal|author=S.Zeng|title=A review on functionalized gold nanoparticles for biosensing applications |journal=Plasmonics |volume=6|year=2011|pages= 491–506|doi=10.1007/s11468-011-9228-1|issue=3|last2=Yong|first2=Ken-Tye|last3=Roy|first3=Indrajit|last4=Dinh|first4=Xuan-Quyen|last5=Yu|first5=Xia|last6=Luan|first6=Feng|display-authors=etal|url=http://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/swzeng/2011-a%20review%20on%20functionalized%20gold%20nanoparticles%20for%20biosensing%20applications.pdf}}</ref> For example, rodlike particles have both transverse and longitudinal [[Absorption (electromagnetic radiation)|absorption]] peak, and [[anisotropy]] of the shape affects their [[Self-assembly of nanoparticles|self-assembly]].<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | journal =Material Science and Engineering Reports | year = 2009 | volume = 65 | issue = 1–3 | pages = 1–38 | title = Colloidal dispersion of gold nanorods: Historical background, optical properties, seed-mediated synthesis, shape separation and self-assembly | doi = 10.1016/j.mser.2009.02.002 | last1 =Sharma | first1 =Vivek | last2 =Park | first2 =Kyoungweon | last3 =Srinivasarao | first3 =Mohan }}</ref> |

The properties of colloidal gold nanoparticles, and thus their applications, depend strongly upon their size and shape.<ref>{{cite journal|author=S.Zeng|title=A review on functionalized gold nanoparticles for biosensing applications |journal=Plasmonics |volume=6|year=2011|pages= 491–506|doi=10.1007/s11468-011-9228-1|issue=3|last2=Yong|first2=Ken-Tye|last3=Roy|first3=Indrajit|last4=Dinh|first4=Xuan-Quyen|last5=Yu|first5=Xia|last6=Luan|first6=Feng | name-list-format = vanc |display-authors=etal|url=http://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/swzeng/2011-a%20review%20on%20functionalized%20gold%20nanoparticles%20for%20biosensing%20applications.pdf}}</ref> For example, rodlike particles have both transverse and longitudinal [[Absorption (electromagnetic radiation)|absorption]] peak, and [[anisotropy]] of the shape affects their [[Self-assembly of nanoparticles|self-assembly]].<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | journal =Material Science and Engineering Reports | year = 2009 | volume = 65 | issue = 1–3 | pages = 1–38 | title = Colloidal dispersion of gold nanorods: Historical background, optical properties, seed-mediated synthesis, shape separation and self-assembly | doi = 10.1016/j.mser.2009.02.002 | last1 =Sharma | first1 =Vivek | last2 =Park | first2 =Kyoungweon | last3 =Srinivasarao | first3 =Mohan | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:Vintage cranberry glass.jpg|thumb|left|This [[cranberry glass]] bowl was made by adding a gold salt (probably gold chloride) to molten glass.]] |

[[File:Vintage cranberry glass.jpg|thumb|left|This [[cranberry glass]] bowl was made by adding a gold salt (probably gold chloride) to molten glass.]] |

||

Used since ancient times as a method of [[Stained glass|staining glass]] colloidal gold was used in the 4th-century [[Lycurgus Cup]], which changes color depending on the location of light source.<ref>{{Cite web|title = The Lycurgus Cup|url = https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=61219&partId=1&searchText=Lycurgus%2520Cup|website = British Museum|access-date = 2015-12-04}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Freestone|first=Ian|last2=Meeks|first2=Nigel|last3=Sax|first3=Margaret|last4=Higgitt|first4=Catherine|title=The Lycurgus Cup — A Roman nanotechnology |journal=Gold Bulletin|language=en|volume=40|issue=4|pages=270–277|doi=10.1007/BF03215599 |year=2007}}</ref> |

Used since ancient times as a method of [[Stained glass|staining glass]] colloidal gold was used in the 4th-century [[Lycurgus Cup]], which changes color depending on the location of light source.<ref>{{Cite web|title = The Lycurgus Cup|url = https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=61219&partId=1&searchText=Lycurgus%2520Cup|website = British Museum|access-date = 2015-12-04}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Freestone|first=Ian|last2=Meeks|first2=Nigel|last3=Sax|first3=Margaret|last4=Higgitt|first4=Catherine | name-list-format = vanc |title=The Lycurgus Cup — A Roman nanotechnology |journal=Gold Bulletin|language=en|volume=40|issue=4|pages=270–277|doi=10.1007/BF03215599 |year=2007}}</ref> |

||

During the [[Middle Ages]], soluble gold, a solution containing [[Gold salts|gold salt]], had a reputation for its curative property for various diseases. In 1618, [[Francis Anthony]], a philosopher and member of the medical profession, published a book called ''Panacea Aurea, sive tractatus duo de ipsius Auro Potabili''<ref>{{Cite book|title = Panacea aurea sive Tractatus duo de ipsius auro potabili|last = Antonii|first = Francisci|publisher = Ex Bibliopolio Frobeniano|year = 1618|isbn = |location = |pages = }}</ref> (Latin: gold potion, or two treatments of [[Drinking water|potable]] gold). The book introduces information on the formation of colloidal gold and its medical uses. About half a century later, English botanist [[Nicholas Culpeper|Nicholas Culpepper]] published book in 1656, ''Treatise of Aurum Potabile'',<ref>{{Cite book|title = Mr. Culpepper's Treatise of aurum potabile Being a description of the three-fold world, viz. elementary celestial intellectual containing the knowledge necessary to the study of hermetick philosophy. Faithfully written by him in his life-time, and since his death, published by his wife.|last = Culpeper|first = Nicholas|publisher = |year = 1657|isbn = |location = London|pages = }}</ref> solely discussing the medical uses of colloidal gold. |

During the [[Middle Ages]], soluble gold, a solution containing [[Gold salts|gold salt]], had a reputation for its curative property for various diseases. In 1618, [[Francis Anthony]], a philosopher and member of the medical profession, published a book called ''Panacea Aurea, sive tractatus duo de ipsius Auro Potabili''<ref>{{Cite book|title = Panacea aurea sive Tractatus duo de ipsius auro potabili|last = Antonii|first = Francisci|publisher = Ex Bibliopolio Frobeniano|year = 1618|isbn = |location = |pages = }}</ref> (Latin: gold potion, or two treatments of [[Drinking water|potable]] gold). The book introduces information on the formation of colloidal gold and its medical uses. About half a century later, English botanist [[Nicholas Culpeper|Nicholas Culpepper]] published book in 1656, ''Treatise of Aurum Potabile'',<ref>{{Cite book|title = Mr. Culpepper's Treatise of aurum potabile Being a description of the three-fold world, viz. elementary celestial intellectual containing the knowledge necessary to the study of hermetick philosophy. Faithfully written by him in his life-time, and since his death, published by his wife.|last = Culpeper|first = Nicholas|publisher = |year = 1657|isbn = |location = London|pages = }}</ref> solely discussing the medical uses of colloidal gold. |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Modern scientific evaluation of colloidal gold did not begin until [[Michael Faraday|Michael Faraday's]] work in the 1850s.<ref name="ref2">V. R. Reddy, "Gold Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications" '''2006''', 1791, and references therein</ref><ref>Michael Faraday, ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'', London, 1857</ref> In 1856, in a basement laboratory of [[Royal Institution]], Faraday accidentally created a ruby red solution while mounting pieces of gold leaf onto microscope slides.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Michael Faraday's gold colloids {{!}} The Royal Institution: Science Lives Here|url = http://www.rigb.org/our-history/iconic-objects/iconic-objects-list/faraday-gold-colloids|website = www.rigb.org|access-date = 2015-12-04}}</ref> Since he was already interested in the properties of light and matter, Faraday further investigated the optical properties of the colloidal gold. He prepared the first pure sample of colloidal gold, which he called 'activated gold', in 1857. He used [[phosphorus]] to [[Redox|reduce]] a solution of gold chloride. The colloidal gold Faraday made 150 years ago is still optically active. For a long time, the composition of the 'ruby' gold was unclear. Several chemists suspected it to be a gold [[tin]] compound, due to its preparation.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = Annalen der Physik | year = 1832 | volume = 101 | issue = 8 | pages = 629–630 | title = Ueber den Cassius'schen Goldpurpur | last = Gay-Lussac | doi = 10.1002/andp.18321010809 | bibcode = 1832AnP...101..629G }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal = Annalen der Physik | volume = 98 | issue = 6 | pages = 306–308 | title = Ueber den Cassius' schen Goldpurpur | first = J. J. | last = Berzelius | doi = 10.1002/andp.18310980613 | year = 1831 | bibcode = 1831AnP....98..306B }}</ref> Faraday recognized that the color was actually due to the miniature size of the gold particles. He noted the [[light scattering]] properties of suspended gold microparticles, which is now called [[Tyndall effect|Faraday-Tyndall effect]].<ref>{{cite journal | title = Experimental Relations of Gold (and Other Metals) to Light, | first = M. | last =Faraday | journal = Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society | year = 1857 | volume = 147 | pages = 145 | doi = 10.1098/rstl.1857.0011}}</ref> |

Modern scientific evaluation of colloidal gold did not begin until [[Michael Faraday|Michael Faraday's]] work in the 1850s.<ref name="ref2">V. R. Reddy, "Gold Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications" '''2006''', 1791, and references therein</ref><ref>Michael Faraday, ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'', London, 1857</ref> In 1856, in a basement laboratory of [[Royal Institution]], Faraday accidentally created a ruby red solution while mounting pieces of gold leaf onto microscope slides.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Michael Faraday's gold colloids {{!}} The Royal Institution: Science Lives Here|url = http://www.rigb.org/our-history/iconic-objects/iconic-objects-list/faraday-gold-colloids|website = www.rigb.org|access-date = 2015-12-04}}</ref> Since he was already interested in the properties of light and matter, Faraday further investigated the optical properties of the colloidal gold. He prepared the first pure sample of colloidal gold, which he called 'activated gold', in 1857. He used [[phosphorus]] to [[Redox|reduce]] a solution of gold chloride. The colloidal gold Faraday made 150 years ago is still optically active. For a long time, the composition of the 'ruby' gold was unclear. Several chemists suspected it to be a gold [[tin]] compound, due to its preparation.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = Annalen der Physik | year = 1832 | volume = 101 | issue = 8 | pages = 629–630 | title = Ueber den Cassius'schen Goldpurpur | last = Gay-Lussac | doi = 10.1002/andp.18321010809 | bibcode = 1832AnP...101..629G }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal = Annalen der Physik | volume = 98 | issue = 6 | pages = 306–308 | title = Ueber den Cassius' schen Goldpurpur | first = J. J. | last = Berzelius | doi = 10.1002/andp.18310980613 | year = 1831 | bibcode = 1831AnP....98..306B }}</ref> Faraday recognized that the color was actually due to the miniature size of the gold particles. He noted the [[light scattering]] properties of suspended gold microparticles, which is now called [[Tyndall effect|Faraday-Tyndall effect]].<ref>{{cite journal | title = Experimental Relations of Gold (and Other Metals) to Light, | first = M. | last =Faraday | journal = Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society | year = 1857 | volume = 147 | pages = 145 | doi = 10.1098/rstl.1857.0011}}</ref> |

||

In 1898, [[Richard Adolf Zsigmondy]] prepared the first colloidal gold in diluted solution.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1925/zsigmondy-lecture.pdf | first = Richard | last = Zsigmondy| title = Properties of colloids | publisher = Nobel Foundation | date = December 11, 1926 | access-date = 2009-01-23}}</ref> Apart from Zsigmondy, [[Theodor Svedberg]], who invented [[ultracentrifugation]], and [[Gustav Mie]], who provided the [[Mie Scattering|theory for scattering and absorption by spherical particles]], were also interested in the synthesis and properties of colloidal gold.<ref name="ReferenceA" /><ref>{{cite journal|title=Size dependence of Au NP-enhanced surface plasmon resonance based on differential phase measurement |journal=Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical |year=2013|doi=10.1016/j.snb.2012.09.073|volume=176|pages=1128|last1=Zeng|first1=Shuwen|last2=Yu|first2=Xia|last3=Law|first3=Wing-Cheung|last4=Zhang|first4=Yating|last5=Hu|first5=Rui|last6=Dinh|first6=Xuan-Quyen|last7= |

In 1898, [[Richard Adolf Zsigmondy]] prepared the first colloidal gold in diluted solution.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1925/zsigmondy-lecture.pdf | first = Richard | last = Zsigmondy| title = Properties of colloids | publisher = Nobel Foundation | date = December 11, 1926 | access-date = 2009-01-23}}</ref> Apart from Zsigmondy, [[Theodor Svedberg]], who invented [[ultracentrifugation]], and [[Gustav Mie]], who provided the [[Mie Scattering|theory for scattering and absorption by spherical particles]], were also interested in the synthesis and properties of colloidal gold.<ref name="ReferenceA" /><ref>{{cite journal|title=Size dependence of Au NP-enhanced surface plasmon resonance based on differential phase measurement |journal=Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical |year=2013 |doi=10.1016/j.snb.2012.09.073 |volume=176|pages=1128|last1=Zeng |first1=Shuwen |last2=Yu |first2=Xia |last3=Law |first3=Wing-Cheung |last4=Zhang |first4=Yating |last5=Hu |first5=Rui |last6=Dinh |first6=Xuan-Quyen |last7=H o|first7=Ho-Pui |last8=Yong |first8=Ken-Tye | name-list-format = vanc |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268225952_Fig._S1 }}</ref> |

||

With advances in various analytical technologies in the 20th century, studies on gold nanoparticles has accelerated. Advanced microscopy methods, such as [[atomic force microscopy]] and [[Electron microscope|electron microscopy]], have contributed the most to nanoparticle research. Due to their comparably easy synthesis and high stability, various gold particles have been studied for their practical uses. Different types of gold nanoparticle are already used in many industries, such as medicine and electronics. For example, several [[Food and Drug Administration|FDA]]-approved nanoparticles are currently used in [[drug delivery]].<ref>{{Cite book|title = Nanoparticle Therapeutics: FDA Approval, Clinical Trials, Regulatory Pathways, and Case Study - Springer|url = https://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1007%2F978-1-61779-052-2_21|publisher = Humana Press|date = 2011-01-01|isbn = 978-1-61779-051-5|series = Methods in Molecular Biology|doi = 10.1007/978-1-61779-052-2_21|editor-first = Sarah J.|editor-last = Hurst}}</ref> |

With advances in various analytical technologies in the 20th century, studies on gold nanoparticles has accelerated. Advanced microscopy methods, such as [[atomic force microscopy]] and [[Electron microscope|electron microscopy]], have contributed the most to nanoparticle research. Due to their comparably easy synthesis and high stability, various gold particles have been studied for their practical uses. Different types of gold nanoparticle are already used in many industries, such as medicine and electronics. For example, several [[Food and Drug Administration|FDA]]-approved nanoparticles are currently used in [[drug delivery]].<ref>{{Cite book|title = Nanoparticle Therapeutics: FDA Approval, Clinical Trials, Regulatory Pathways, and Case Study - Springer|url = https://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1007%2F978-1-61779-052-2_21|publisher = Humana Press|date = 2011-01-01|isbn = 978-1-61779-051-5|series = Methods in Molecular Biology|doi = 10.1007/978-1-61779-052-2_21|editor-first = Sarah J.|editor-last = Hurst}}</ref> |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

=== Optical === |

=== Optical === |

||

Colloidal gold has been used by artists for centuries because of the nanoparticle’s interactions with visible light. Gold nanoparticles absorb and scatter light<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Anderson|first=Michele L.|last2=Morris|first2=Catherine A.|last3=Stroud|first3=Rhonda M.|last4=Merzbacher|first4=Celia I.|last5=Rolison|first5=Debra R.|date=1999-02-01|title=Colloidal Gold Aerogels: Preparation, Properties, and Characterization |journal=Langmuir|volume=15|issue=3|pages=674–681|doi=10.1021/la980784i }}</ref> resulting in colours ranging from vibrant reds to blues to black and finally to clear and colorless, depending on particle size, shape, local refractive index, and aggregation state. These colors occur because of a phenomenon called [[Surface plasmon resonance|Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR)]], in which conduction electrons on the surface of the nanoparticle oscillate in resonance with incident light. |

Colloidal gold has been used by artists for centuries because of the nanoparticle’s interactions with visible light. Gold nanoparticles absorb and scatter light<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Anderson|first=Michele L.|last2=Morris|first2=Catherine A.|last3=Stroud|first3=Rhonda M.|last4=Merzbacher|first4=Celia I.|last5=Rolison|first5=Debra R. | name-list-format = vanc |date=1999-02-01|title=Colloidal Gold Aerogels: Preparation, Properties, and Characterization |journal=Langmuir|volume=15|issue=3|pages=674–681|doi=10.1021/la980784i }}</ref> resulting in colours ranging from vibrant reds to blues to black and finally to clear and colorless, depending on particle size, shape, local refractive index, and aggregation state. These colors occur because of a phenomenon called [[Surface plasmon resonance|Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR)]], in which conduction electrons on the surface of the nanoparticle oscillate in resonance with incident light. |

||

==== Effect of size ==== |

==== Effect of size ==== |

||

As a general rule, the wavelength of light absorbed increases as a function of increasing nano particle size.<ref name="Link 4212–4217">{{Cite journal|last=Link|first=Stephan|last2=El-Sayed|first2=Mostafa A.|date=1999-05-01|title=Size and Temperature Dependence of the Plasmon Absorption of Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles |journal=The Journal of Physical Chemistry B|volume=103|issue=21|pages=4212–4217|doi=10.1021/jp984796o }}</ref> For example, pseudo-spherical gold nanoparticles with diameters ~ 30 nm have a peak LSPR absorption at ~530 nm.<ref name="Link 4212–4217"/>{{clarify|reason=a single absorption peak for a single particle size is not sufficient to illustrate the rule expressed in the previous sentence|date=April 2018}} |

As a general rule, the wavelength of light absorbed increases as a function of increasing nano particle size.<ref name="Link 4212–4217">{{Cite journal|last=Link|first=Stephan|last2=El-Sayed|first2=Mostafa A. | name-list-format = vanc |date=1999-05-01|title=Size and Temperature Dependence of the Plasmon Absorption of Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles |journal=The Journal of Physical Chemistry B|volume=103|issue=21|pages=4212–4217|doi=10.1021/jp984796o }}</ref> For example, pseudo-spherical gold nanoparticles with diameters ~ 30 nm have a peak LSPR absorption at ~530 nm.<ref name="Link 4212–4217"/>{{clarify|reason=a single absorption peak for a single particle size is not sufficient to illustrate the rule expressed in the previous sentence|date=April 2018}} |

||

==== Effect of local refractive index ==== |

==== Effect of local refractive index ==== |

||

Changes in the apparent color of a gold nanoparticle solution can also be caused by the environment in which the colloidal gold is suspended<ref name="Ghosh 13963–13971">{{Cite journal|last=Ghosh|first=Sujit Kumar|last2=Nath|first2=Sudip|last3=Kundu|first3=Subrata|last4=Esumi|first4=Kunio|last5=Pal|first5=Tarasankar|date=2004-09-01|title=Solvent and Ligand Effects on the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) of Gold Colloids |journal=The Journal of Physical Chemistry B|volume=108|issue=37|pages=13963–13971|doi=10.1021/jp047021q }}</ref><ref name="Underwood 3427–3430">{{Cite journal|last=Underwood|first=Sylvia|last2=Mulvaney|first2=Paul|date=1994-10-01|title=Effect of the Solution Refractive Index on the Color of Gold Colloids |journal=Langmuir|volume=10|issue=10|pages=3427–3430|doi=10.1021/la00022a011 }}</ref> The optical properties of gold nanoparticles depends on the refractive index near the nanoparticle surface, therefore both the molecules directly attached to the nanoparticle surface (i.e. nanoparticle ligands) and/or the nanoparticle [[solvent]] both may influence observed optical features.<ref name="Ghosh 13963–13971"/> As the refractive index near the gold surface increases, the NP LSPR will shift to longer wavelengths<ref name="Underwood 3427–3430"/> In addition to solvent environment, the [[Complex index of refraction#Complex refractive index|extinction peak]] can be tuned by coating the nanoparticles with non-conducting shells such as silica, bio molecules, or aluminium oxide.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Xing|first=Shuangxi|last2=Tan|first2=Li Huey|last3=Yang|first3=Miaoxin|last4=Pan|first4=Ming|last5=Lv|first5=Yunbo|last6=Tang|first6=Qinghu|last7=Yang|first7=Yanhui|last8=Chen|first8=Hongyu|date=2009-05-12|title=Highly controlled core/shell structures: tunable conductive polymer shells on gold nanoparticles and nanochains |journal=Journal of Materials Chemistry|language=en|volume=19|issue=20|doi=10.1039/b900993k |page=3286}}</ref> |

Changes in the apparent color of a gold nanoparticle solution can also be caused by the environment in which the colloidal gold is suspended<ref name="Ghosh 13963–13971">{{Cite journal|last=Ghosh|first=Sujit Kumar|last2=Nath|first2=Sudip|last3=Kundu|first3=Subrata|last4=Esumi|first4=Kunio|last5=Pal|first5=Tarasankar | name-list-format = vanc |date=2004-09-01|title=Solvent and Ligand Effects on the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) of Gold Colloids |journal=The Journal of Physical Chemistry B|volume=108|issue=37|pages=13963–13971|doi=10.1021/jp047021q }}</ref><ref name="Underwood 3427–3430">{{Cite journal|last=Underwood|first=Sylvia|last2=Mulvaney|first2=Paul| name-list-format = vanc |date=1994-10-01|title=Effect of the Solution Refractive Index on the Color of Gold Colloids |journal=Langmuir|volume=10|issue=10|pages=3427–3430|doi=10.1021/la00022a011 }}</ref> The optical properties of gold nanoparticles depends on the refractive index near the nanoparticle surface, therefore both the molecules directly attached to the nanoparticle surface (i.e. nanoparticle ligands) and/or the nanoparticle [[solvent]] both may influence observed optical features.<ref name="Ghosh 13963–13971"/> As the refractive index near the gold surface increases, the NP LSPR will shift to longer wavelengths<ref name="Underwood 3427–3430"/> In addition to solvent environment, the [[Complex index of refraction#Complex refractive index|extinction peak]] can be tuned by coating the nanoparticles with non-conducting shells such as silica, bio molecules, or aluminium oxide.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Xing |first=Shuangxi |last2=Tan |first2=Li Huey |last3=Yang |first3=Miaoxin |last4=Pan |first4=Ming |last5=Lv |first5=Yunbo |last6=Tang |first6=Qinghu|last7=Yang|first7=Yanhui|last8=Chen|first8=Hongyu | name-list-format = vanc |date=2009-05-12|title=Highly controlled core/shell structures: tunable conductive polymer shells on gold nanoparticles and nanochains |journal=Journal of Materials Chemistry|language=en|volume=19|issue=20|doi=10.1039/b900993k |page=3286}}</ref> |

||

==== Effect of aggregation ==== |

==== Effect of aggregation ==== |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

===Drug delivery system=== |

===Drug delivery system=== |

||

Gold nanoparticles can be used to optimize the biodistribution of drugs to diseased organs, tissues or cells, in order to improve and target drug delivery.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Han G, Ghosh P, Rotello VM | title = Functionalized gold nanoparticles for drug delivery | journal = Nanomedicine | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | pages = 113–23 | date = February 2007 | pmid = 17716197 | doi = 10.2217/17435889.2.1.113 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | |

Gold nanoparticles can be used to optimize the biodistribution of drugs to diseased organs, tissues or cells, in order to improve and target drug delivery.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Han G, Ghosh P, Rotello VM | title = Functionalized gold nanoparticles for drug delivery | journal = Nanomedicine | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | pages = 113–23 | date = February 2007 | pmid = 17716197 | doi = 10.2217/17435889.2.1.113 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Han G, Ghosh P, Rotello VM | title = Multi-functional gold nanoparticles for drug delivery | journal = Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology | volume = 620 | issue = | pages = 48–56 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18217334 }}</ref> |

||

Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery is feasible only if the drug distribution is otherwise inadequate. These cases include drug targeting of unstable ([[protein]]s, [[Small interfering RNA|siRNA]], [[DNA]]), delivery to the difficult sites (brain, retina, tumors, intracellular organelles) and drugs with serious side effects (e.g. anti-cancer agents). The performance of the nanoparticles depends on the size and surface functionalities in the particles. Also, the drug release and particle disintegration can vary depending on the system (e.g. biodegradable polymers sensitive to pH). An optimal nanodrug delivery system ensures that the active drug is available at the site of action for the correct time and duration, and their concentration should be above the minimal effective concentration (MEC) and below the minimal toxic concentration (MTC).<ref>{{cite journal | |

Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery is feasible only if the drug distribution is otherwise inadequate. These cases include drug targeting of unstable ([[protein]]s, [[Small interfering RNA|siRNA]], [[DNA]]), delivery to the difficult sites (brain, retina, tumors, intracellular organelles) and drugs with serious side effects (e.g. anti-cancer agents). The performance of the nanoparticles depends on the size and surface functionalities in the particles. Also, the drug release and particle disintegration can vary depending on the system (e.g. biodegradable polymers sensitive to pH). An optimal nanodrug delivery system ensures that the active drug is available at the site of action for the correct time and duration, and their concentration should be above the minimal effective concentration (MEC) and below the minimal toxic concentration (MTC).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Langer R | title = Biomaterials in drug delivery and tissue engineering: one laboratory's experience | journal = Accounts of Chemical Research | volume = 33 | issue = 2 | pages = 94–101 | date = February 2000 | pmid = 10673317 | doi = 10.1021/ar9800993 }}</ref> |

||

Gold nanoparticles are being investigated as carriers for drugs such as [[Paclitaxel]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gibson JD, Khanal BP, Zubarev ER | title = Paclitaxel-functionalized gold nanoparticles | journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 129 | issue = 37 | pages = 11653–61 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17718495 | doi = 10.1021/ja075181k }}</ref> The administration of hydrophobic drugs require [[molecular encapsulation]] and it is found that nanosized particles are particularly efficient in evading the [[reticuloendothelial system]]. |

Gold nanoparticles are being investigated as carriers for drugs such as [[Paclitaxel]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gibson JD, Khanal BP, Zubarev ER | title = Paclitaxel-functionalized gold nanoparticles | journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 129 | issue = 37 | pages = 11653–61 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17718495 | doi = 10.1021/ja075181k }}</ref> The administration of hydrophobic drugs require [[molecular encapsulation]] and it is found that nanosized particles are particularly efficient in evading the [[reticuloendothelial system]]. |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

In cancer research, colloidal gold can be used to target tumors and provide detection using SERS ([[surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy]]) ''in vivo''. These gold nanoparticles are surrounded with Raman reporters, which provide light emission that is over 200 times brighter than [[quantum dots]]. It was found that the Raman reporters were stabilized when the nanoparticles were encapsulated with a thiol-modified [[polyethylene glycol]] coat. This allows for compatibility and circulation ''in vivo''. To specifically target tumor cells, the [[polyethylene]]gylated gold particles are conjugated with an antibody (or an antibody fragment such as scFv), against, e.g. [[epidermal growth factor receptor]], which is sometimes overexpressed in cells of certain cancer types. Using SERS, these pegylated gold nanoparticles can then detect the location of the tumor.<ref>Qian, Ximei. ''In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags.'' Nature Biotechnology. 2008. Vol 26 No 1.</ref> |

In cancer research, colloidal gold can be used to target tumors and provide detection using SERS ([[surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy]]) ''in vivo''. These gold nanoparticles are surrounded with Raman reporters, which provide light emission that is over 200 times brighter than [[quantum dots]]. It was found that the Raman reporters were stabilized when the nanoparticles were encapsulated with a thiol-modified [[polyethylene glycol]] coat. This allows for compatibility and circulation ''in vivo''. To specifically target tumor cells, the [[polyethylene]]gylated gold particles are conjugated with an antibody (or an antibody fragment such as scFv), against, e.g. [[epidermal growth factor receptor]], which is sometimes overexpressed in cells of certain cancer types. Using SERS, these pegylated gold nanoparticles can then detect the location of the tumor.<ref>Qian, Ximei. ''In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags.'' Nature Biotechnology. 2008. Vol 26 No 1.</ref> |

||

Gold nanoparticles accumulate in tumors, due to the leakiness of tumor vasculature, and can be used as contrast agents for enhanced imaging in a time-resolved optical tomography system using short-pulse lasers for skin cancer detection in mouse model. It is found that intravenously administrated spherical gold nanoparticles broadened the temporal profile of reflected optical signals and enhanced the contrast between surrounding normal tissue and tumors.<ref>{{cite journal | |

Gold nanoparticles accumulate in tumors, due to the leakiness of tumor vasculature, and can be used as contrast agents for enhanced imaging in a time-resolved optical tomography system using short-pulse lasers for skin cancer detection in mouse model. It is found that intravenously administrated spherical gold nanoparticles broadened the temporal profile of reflected optical signals and enhanced the contrast between surrounding normal tissue and tumors.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sajjadi AY, Suratkar AA, Mitra KK, Grace MS | year = 2012 | title = Short-Pulse Laser-Based System for Detection of Tumors: Administration of Gold Nanoparticles Enhances Contrast | journal = J. Nanotechnol. Eng. Med. | volume = 3 | issue = 2| page = 021002 | doi = 10.1115/1.4007245 }}</ref> |

||

[[File:tumor targeting.png|framed|right|Tumor targeting|framed|Tumor targeting via multifunctional nanocarriers. Cancer cells reduce adhesion to neighboring cells and migrate into the vasculature-rich stroma. Once at the vasculature, cells can freely enter the bloodstream. Once the tumor is directly connected to the main blood circulation system, multifunctional nanocarriers can interact directly with cancer cells and effectively target tumors.]] |

[[File:tumor targeting.png|framed|right|Tumor targeting|framed|Tumor targeting via multifunctional nanocarriers. Cancer cells reduce adhesion to neighboring cells and migrate into the vasculature-rich stroma. Once at the vasculature, cells can freely enter the bloodstream. Once the tumor is directly connected to the main blood circulation system, multifunctional nanocarriers can interact directly with cancer cells and effectively target tumors.]] |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

===Gold nanoparticle based biosensor=== |

===Gold nanoparticle based biosensor=== |

||

Gold nanoparticles are incorporated into [[biosensor]]s to enhance its stability, sensitivity, and selectivity.<ref name="review">Xu |

Gold nanoparticles are incorporated into [[biosensor]]s to enhance its stability, sensitivity, and selectivity.<ref name="review">{{cite journal | vauthors = Xu S | title = Gold nanoparticle-based biosensors | journal = Gold Bulletin | year = 2010 | volume = 43 | pages = 29–41 }}</ref> Nanoparticle properties such as small size, high surface-to-volume ratio, and high surface energy allow immobilization of large range of biomolecules. Gold nanoparticle, in particular, could also act as "electron wire" to transport electrons and its amplification effect on electromagnetic light allows it to function as signal amplifiers.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang J, Polsky R, Xu D | year = 2001 | title = Silver-Enhanced Colloidal Gold Electrochemical Stripping Detection of DNA Hybridization| journal = Langmuir | volume = 17 | issue = | page = 5739 | doi=10.1021/la011002f}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang J, Xu D, Polsky R | title = Magnetically-induced solid-state electrochemical detection of DNA hybridization | journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 124 | issue = 16 | pages = 4208–9 | date = April 2002 | pmid = 11960439 | doi = 10.1021/ja0255709 }}</ref> Main types of gold nanoparticle based biosensors are optical and electrochemical biosensor. |

||

====Optical biosensor==== |

====Optical biosensor==== |

||

[[File:Gold nanoparticles as indicators.jpg|thumb|441x441px|Gold nanoparticle-based (Au-NP) biosensor for [[Glutathione]] (GSH). The AuNPs are [[Functional group|functionalised]] with a chemical group that binds to GSH and makes the NPs partially collapse, and thus change colour. The exact amount of GSH can be derived via [[Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy|UV-vis spectroscopy]] through a [[calibration curve]].]] |

[[File:Gold nanoparticles as indicators.jpg|thumb|441x441px|Gold nanoparticle-based (Au-NP) biosensor for [[Glutathione]] (GSH). The AuNPs are [[Functional group|functionalised]] with a chemical group that binds to GSH and makes the NPs partially collapse, and thus change colour. The exact amount of GSH can be derived via [[Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy|UV-vis spectroscopy]] through a [[calibration curve]].]] |

||

Gold nanoparticles improve the sensitivity of optical sensor by response to the change in local refractive index. The angle of the incidence light for surface plasmon resonance, an interaction between light wave and conducting electrons in metal, changes when other substances are bounded to the metal surface.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Daniel MC, Astruc D | title = Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology | journal = Chemical Reviews | volume = 104 | issue = 1 | pages = 293–346 | date = January 2004 | pmid = 14719978 | doi = 10.1021/cr030698+ }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hu M, Chen J, Li ZY, Au L, Hartland GV, Li X, Marquez M, Xia Y | title = Gold nanostructures: engineering their plasmonic properties for biomedical applications | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 35 | issue = 11 | pages = 1084–94 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 17057837 | doi = 10.1039/b517615h }}</ref> Because gold is very sensitive to its surroundings' dielectric constant,<ref>{{cite journal | |

Gold nanoparticles improve the sensitivity of optical sensor by response to the change in local refractive index. The angle of the incidence light for surface plasmon resonance, an interaction between light wave and conducting electrons in metal, changes when other substances are bounded to the metal surface.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Daniel MC, Astruc D | title = Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology | journal = Chemical Reviews | volume = 104 | issue = 1 | pages = 293–346 | date = January 2004 | pmid = 14719978 | doi = 10.1021/cr030698+ }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hu M, Chen J, Li ZY, Au L, Hartland GV, Li X, Marquez M, Xia Y | title = Gold nanostructures: engineering their plasmonic properties for biomedical applications | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 35 | issue = 11 | pages = 1084–94 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 17057837 | doi = 10.1039/b517615h }}</ref> Because gold is very sensitive to its surroundings' dielectric constant,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Link S, El-Sayed MA | year = 1996 | title = Spectral Properties and Relaxation Dynamics of Surface Plasmon Electronic Oscillations in Gold and Silver Nanodots and Nanorods| doi = 10.1021/jp9917648 | journal = J. Phys. Chem. B | volume = 103 | issue = | page = 8410 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Mulvaney | first1 = P. | year = 1996 | title = Surface Plasmon Spectroscopy of Nanosized Metal Particles| journal = Langmuir | volume = 12 | issue = | page = 788 | doi=10.1021/la9502711}}</ref> binding of an analyte would significantly shift gold nanoparticle's SPR and therefore allow more sensitive detection. Gold nanoparticle could also amplify the SPR signal.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lin HY, Chen CT, Chen YC | title = Detection of phosphopeptides by localized surface plasma resonance of titania-coated gold nanoparticles immobilized on glass substrates | journal = Analytical Chemistry | volume = 78 | issue = 19 | pages = 6873–8 | date = October 2006 | pmid = 17007509 | doi = 10.1021/ac060833t }}</ref> When the plasmon wave pass through the gold nanoparticle, the charge density in the wave and the electron I the gold interacted and resulted in higher energy response, so called electron coupling.<ref name="review" /> Since the analyte and bio-receptor now bind to the gold, it increases the apparent mass of the analyte and therefore amplified the signal.<ref name="review" /> |

||

These properties had been used to build DNA sensor with 1000-fold sensitive than without the Au NP.<ref>{{cite journal | |

These properties had been used to build DNA sensor with 1000-fold sensitive than without the Au NP.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = He L, Musick MD, Nicewarner SR, Salinas FG | year = 2000 | title = Colloidal Au-Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance for Ultrasensitive Detection of DNA Hybridization| doi = 10.1021/ja001215b | journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 122 | issue = | page = 9071 }}</ref> Humidity senor was also built by altering the atom interspacing between molecules with humidity change, the interspacing change would also result in a change of the Au NP's LSPR.<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2000 | title = Local plasmon sensor with gold colloid monolayers deposited upon glass substrates| doi = 10.1364/OL.25.000372 | journal = Opt Lett | volume = 25 | issue = | page = 372 | last1 = Okamoto | first1 = Takayuki | last2 = Yamaguchi | first2 = Ichirou | last3 = Kobayashi | first3 = Tetsushi | name-list-format = vanc | bibcode = 2000OptL...25..372O}}</ref> |

||

====Electrochemical biosensor==== |

====Electrochemical biosensor==== |

||

Electrochemical sensor convert biological information into electrical signals that could be detected. The conductivity and biocompatibility of Au NP allow it to act as "electron wire".<ref name="review" /> It transfers electron between the electrode and the active site of the enzyme.<ref>{{cite journal | |

Electrochemical sensor convert biological information into electrical signals that could be detected. The conductivity and biocompatibility of Au NP allow it to act as "electron wire".<ref name="review" /> It transfers electron between the electrode and the active site of the enzyme.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Brown KR, Fox P, Natan MJ | year = 1996 | title = Morphology-Dependent Electrochemistry of Cytochromecat Au Colloid-Modified SnO2Electrodes| journal = Journal of the American Chemical Society | volume = 118 | issue = | page = 1154 | doi=10.1021/ja952951w}}</ref> It could be accomplished in two ways: attach the Au NP to either the enzyme or the electrode. GNP-glucose oxidase monolayer electrode was constructed use these two methods.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Xiao Y, Patolsky F, Katz E, Hainfeld JF, Willner I | title = "Plugging into Enzymes": nanowiring of redox enzymes by a gold nanoparticle | journal = Science | volume = 299 | issue = 5614 | pages = 1877–81 | date = March 2003 | pmid = 12649477 | doi = 10.1126/science.1080664 | bibcode = 2003Sci...299.1877X }}</ref> The Au NP allowed more freedom in the enzyme's orientation and therefore more sensitive and stable detection. Au NP also acts as immobilization platform for the enzyme. Most biomolecules denatures or lose its activity when interacted with the electrode.<ref name="review" /> The biocompatibility and high surface energy of Au allow it to bind to a large amount of protein without altering its activity and results in a more sensitive sensor.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Gole | first1 = A. | display-authors = 1 | last2 = et al | year = 2001 | title = Pepsin−Gold Colloid Conjugates: Preparation, Characterization, and Enzymatic Activity| journal = Langmuir | volume = 17 | issue = | page = 1674 | doi=10.1021/la001164w}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Gole | first1 = A. | display-authors = 1 | last2 = et al | year = 2002 | title = Studies on the formation of bioconjugates of Endoglucanase with colloidal gold| journal = Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces | volume = 25 | issue = | page = 129 | doi=10.1016/s0927-7765(01)00301-0}}</ref> Moreover, Au NP also catalyzes biological reactions.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Valden M, Lai X, Goodman DW | title = Onset of catalytic activity of gold clusters on titania with the appearance of nonmetallic properties | journal = Science | volume = 281 | issue = 5383 | pages = 1647–50 | date = September 1998 | pmid = 9733505 | doi = 10.1126/science.281.5383.1647 | bibcode = 1998Sci...281.1647V }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lou Y, Maye MM, Han L, Zhong CJ | year = 2001| title = Gold–platinum alloy nanoparticle assembly as catalyst for methanol electrooxidation| doi = 10.1039/b008669j | journal = Chemical Communications | volume = 2001 | issue = | page = 473 }}</ref> Gold nanoparticle under 2 nm has shown [[Heterogeneous gold catalysis|catalytic activity]] to the oxidation of styrene.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Turner M, Golovko VB, Vaughan OP, Abdulkin P, Berenguer-Murcia A, Tikhov MS, Johnson BF, Lambert RM | title = Selective oxidation with dioxygen by gold nanoparticle catalysts derived from 55-atom clusters | journal = Nature | volume = 454 | issue = 7207 | pages = 981–3 | date = August 2008 | pmid = 18719586 | doi = 10.1038/nature07194 | bibcode = 2008Natur.454..981T }}</ref> |

||

=== Thin films === |

=== Thin films === |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

=== Ligand removal === |

=== Ligand removal === |

||

In many cases, as in various high-temperature catalytic applications of Au, the removal of the capping ligands produces more desirable physicochemical properties.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tyo EC, Vajda S | title = Catalysis by clusters with precise numbers of atoms | journal = Nature Nanotechnology | volume = 10 | issue = 7 | pages = 577–88 | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26139144 | doi = 10.1038/nnano.2015.140 | bibcode = 2015NatNa..10..577T }}</ref> The removal of ligands from colloidal gold while maintaining a relatively constant number of Au atoms per Au NP can be difficult due to the tendency for these bare clusters to aggregate. The removal of ligands is partially achievable by simply washing away all excess capping ligands, though this method is ineffective in removing all capping ligand. More often ligand removal achieved under high temperature or light [[ablation]] followed by washing. Alternatively, the ligands can be [[Electroetching|electrochemically etched]] off.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Niu|first=Zhiqiang|last2=Li|first2=Yadong|date=2014-01-14|title=Removal and Utilization of Capping Agents in Nanocatalysis |journal=Chemistry of Materials|volume=26|issue=1|pages=72–83|doi=10.1021/cm4022479 }}</ref> |

In many cases, as in various high-temperature catalytic applications of Au, the removal of the capping ligands produces more desirable physicochemical properties.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tyo EC, Vajda S | title = Catalysis by clusters with precise numbers of atoms | journal = Nature Nanotechnology | volume = 10 | issue = 7 | pages = 577–88 | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26139144 | doi = 10.1038/nnano.2015.140 | bibcode = 2015NatNa..10..577T }}</ref> The removal of ligands from colloidal gold while maintaining a relatively constant number of Au atoms per Au NP can be difficult due to the tendency for these bare clusters to aggregate. The removal of ligands is partially achievable by simply washing away all excess capping ligands, though this method is ineffective in removing all capping ligand. More often ligand removal achieved under high temperature or light [[ablation]] followed by washing. Alternatively, the ligands can be [[Electroetching|electrochemically etched]] off.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Niu|first=Zhiqiang|last2=Li|first2=Yadong | name-list-format = vanc |date=2014-01-14|title=Removal and Utilization of Capping Agents in Nanocatalysis |journal=Chemistry of Materials|volume=26|issue=1|pages=72–83|doi=10.1021/cm4022479 }}</ref> |

||

=== Surface structure and chemical environment === |

=== Surface structure and chemical environment === |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

===Toxicity due to capping ligands=== |

===Toxicity due to capping ligands=== |

||

Some of the capping ligands associated with AuNPs can be toxic while others are nontoxic. In gold nanorods (AuNRs), it has been shown that a strong cytotoxicity was associated with [[Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide|CTAB]]-stabilized AuNRs at low concentration, but it is thought that free CTAB was the culprit in toxicity .<ref name="Cellular uptake">{{cite journal | vauthors = Alkilany AM, Nagaria PK, Hexel CR, Shaw TJ, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD | title = Cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of gold nanorods: molecular origin of cytotoxicity and surface effects | journal = Small | volume = 5 | issue = 6 | pages = 701–8 | date = March 2009 | pmid = 19226599 | doi = 10.1002/smll.200801546 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Takahashi H, Niidome Y, Niidome T, Kaneko K, Kawasaki H, Yamada S | title = Modification of gold nanorods using phosphatidylcholine to reduce cytotoxicity | journal = Langmuir | volume = 22 | issue = 1 | pages = 2–5 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16378388 | doi = 10.1021/la0520029 }}</ref> Modifications that overcoat these AuNRs reduces this toxicity in human colon cancer cells (HT-29) by preventing CTAB molecules from desorbing from the AuNRs back into the solution.<ref name="Cellular uptake" /> |

Some of the capping ligands associated with AuNPs can be toxic while others are nontoxic. In gold nanorods (AuNRs), it has been shown that a strong cytotoxicity was associated with [[Cetyl trimethylammonium bromide|CTAB]]-stabilized AuNRs at low concentration, but it is thought that free CTAB was the culprit in toxicity .<ref name="Cellular uptake">{{cite journal | vauthors = Alkilany AM, Nagaria PK, Hexel CR, Shaw TJ, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD | title = Cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of gold nanorods: molecular origin of cytotoxicity and surface effects | journal = Small | volume = 5 | issue = 6 | pages = 701–8 | date = March 2009 | pmid = 19226599 | doi = 10.1002/smll.200801546 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Takahashi H, Niidome Y, Niidome T, Kaneko K, Kawasaki H, Yamada S | title = Modification of gold nanorods using phosphatidylcholine to reduce cytotoxicity | journal = Langmuir | volume = 22 | issue = 1 | pages = 2–5 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16378388 | doi = 10.1021/la0520029 }}</ref> Modifications that overcoat these AuNRs reduces this toxicity in human colon cancer cells (HT-29) by preventing CTAB molecules from desorbing from the AuNRs back into the solution.<ref name="Cellular uptake" /> |

||

Ligand toxicity can also be seen in AuNPs. Compared to the 90% toxicity of HAuCl4 at the same concentration, AuNPs with carboxylate termini were shown to be non-toxic.<ref name="Rotello Toxicity">{{cite journal | |

Ligand toxicity can also be seen in AuNPs. Compared to the 90% toxicity of HAuCl4 at the same concentration, AuNPs with carboxylate termini were shown to be non-toxic.<ref name="Rotello Toxicity">{{cite journal | vauthors = Goodman CM, McCusker CD, Yilmaz T, Rotello VM | title = Toxicity of gold nanoparticles functionalized with cationic and anionic side chains | journal = Bioconjugate Chemistry | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 897–900 | date = June 2004 | pmid = 15264879 | doi = 10.1021/bo049951i }}</ref> Large AuNPs conjugated with biotin, cysteine, citrate, and glucose were not toxic in human leukemia cells ([[K562]]) for concentrations up to 0.25 M.<ref name="Murphy Jan 2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Connor EE, Mwamuka J, Gole A, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD | title = Gold nanoparticles are taken up by human cells but do not cause acute cytotoxicity | journal = Small | volume = 1 | issue = 3 | pages = 325–7 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 17193451 | doi = 10.1002/smll.2004000093 }}</ref> Also, citrate-capped gold nanospheres (AuNSs) have been proven to be compatible with human blood and did not cause platelet aggregation or an immune response.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dobrovolskaia MA, Patri AK, Zheng J, Clogston JD, Ayub N, Aggarwal P, Neun BW, Hall JB, McNeil SE | title = Interaction of colloidal gold nanoparticles with human blood: effects on particle size and analysis of plasma protein binding profiles | journal = Nanomedicine | volume = 5 | issue = 2 | pages = 106–17 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19071065 | pmc = 3683956 | doi = 10.1016/j.nano.2008.08.001 }}</ref> However, citrate-capped gold nanoparticles sizes 8-37 nm were found to be lethally toxic for mice, causing shorter lifespans, severe sickness, loss of appetite and weight, hair discoloration, and damage to the liver, spleen, and lungs; gold nanoparticles accumulated in the spleen and liver after traveling a section of the immune system.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen YS, Hung YC, Liau I, Huang GS | title = Assessment of the In Vivo Toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles | journal = Nanoscale Research Letters | volume = 4 | issue = 8 | pages = 858–864 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 20596373 | doi = 10.1007/s11671-009-9334-6 | bibcode = 2009NRL.....4..858C }}</ref> |

||

There are mixed-views for [[polyethylene glycol]] (PEG)-modified AuNPs. These AuNPs were found to be toxic in mouse liver by injection, causing cell death and minor inflammation.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cho WS, Cho M, Jeong J, Choi M, Cho HY, Han BS, Kim SH, Kim HO, Lim YT, Chung BH, Jeong J | title = Acute toxicity and pharmacokinetics of 13 nm-sized PEG-coated gold nanoparticles | journal = Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology | volume = 236 | issue = 1 | pages = 16–24 | date = April 2009 | pmid = 19162059 | doi = 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.023 }}</ref> However, AuNPs conjugated with PEG copolymers showed negligible toxicity towards human colon cells ([[Caco-2]]).<ref>{{cite journal | |

There are mixed-views for [[polyethylene glycol]] (PEG)-modified AuNPs. These AuNPs were found to be toxic in mouse liver by injection, causing cell death and minor inflammation.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cho WS, Cho M, Jeong J, Choi M, Cho HY, Han BS, Kim SH, Kim HO, Lim YT, Chung BH, Jeong J | title = Acute toxicity and pharmacokinetics of 13 nm-sized PEG-coated gold nanoparticles | journal = Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology | volume = 236 | issue = 1 | pages = 16–24 | date = April 2009 | pmid = 19162059 | doi = 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.023 }}</ref> However, AuNPs conjugated with PEG copolymers showed negligible toxicity towards human colon cells ([[Caco-2]]).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gref R, Couvreur P, Barratt G, Mysiakine E | title = Surface-engineered nanoparticles for multiple ligand coupling | journal = Biomaterials | volume = 24 | issue = 24 | pages = 4529–37 | date = November 2003 | pmid = 12922162 | doi = 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00348-x }}</ref> |

||

AuNP toxicity also depends on the overall charge of the ligands. In certain doses, AuNSs that have positively-charged ligands are toxic in monkey kidney cells (Cos-1), human red blood cells, and E. coli because of the AuNSs interaction with the negatively-charged cell membrane; AuNSs with negatively-charged ligands have been found to be nontoxic in these species.<ref name="Rotello Toxicity" /> |

AuNP toxicity also depends on the overall charge of the ligands. In certain doses, AuNSs that have positively-charged ligands are toxic in monkey kidney cells (Cos-1), human red blood cells, and E. coli because of the AuNSs interaction with the negatively-charged cell membrane; AuNSs with negatively-charged ligands have been found to be nontoxic in these species.<ref name="Rotello Toxicity" /> |

||

In addition to the previously mentioned ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' experiments, other similar experiments have been performed. Alkylthiolate-AuNPs with trimethlyammonium ligand termini mediate the [[Chromosomal translocation|translocation]] of DNA across mammalian cell membranes ''in vitro'' at a high level, which is detrimental to these cells.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Boisselier E, Astruc D | title = Gold nanoparticles in nanomedicine: preparations, imaging, diagnostics, therapies and toxicity | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 38 | issue = 6 | pages = 1759–82 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19587967 | doi = 10.1039/b806051g }}</ref> Corneal haze in rabbits have been healed ''in vivo'' by using polyethylemnimine-capped gold nanoparticles that were transfected with a gene that promotes wound healing and inhibits corneal [[fibrosis]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tandon A, Sharma A, Rodier JT, Klibanov AM, Rieger FG, Mohan RR | title = BMP7 gene transfer via gold nanoparticles into stroma inhibits corneal fibrosis in vivo | journal = PloS One | volume = 8 | issue = 6 | pages = e66434 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23799103 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0066434 | bibcode = 2013PLoSO...866434T }}</ref> |

In addition to the previously mentioned ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' experiments, other similar experiments have been performed. Alkylthiolate-AuNPs with trimethlyammonium ligand termini mediate the [[Chromosomal translocation|translocation]] of DNA across mammalian cell membranes ''in vitro'' at a high level, which is detrimental to these cells.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Boisselier E, Astruc D | title = Gold nanoparticles in nanomedicine: preparations, imaging, diagnostics, therapies and toxicity | journal = Chemical Society Reviews | volume = 38 | issue = 6 | pages = 1759–82 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19587967 | doi = 10.1039/b806051g }}</ref> Corneal haze in rabbits have been healed ''in vivo'' by using polyethylemnimine-capped gold nanoparticles that were transfected with a gene that promotes wound healing and inhibits corneal [[fibrosis]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tandon A, Sharma A, Rodier JT, Klibanov AM, Rieger FG, Mohan RR | title = BMP7 gene transfer via gold nanoparticles into stroma inhibits corneal fibrosis in vivo | journal = PloS One | volume = 8 | issue = 6 | pages = e66434 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23799103 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0066434 | bibcode = 2013PLoSO...866434T }}</ref> |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

=== Turkevich method === |

=== Turkevich method === |

||

The method pioneered by J. Turkevich et al. in 1951<ref>{{cite journal | |

The method pioneered by J. Turkevich et al. in 1951<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Turkevich J, Stevenson PC, Hillier J | year = 1951 | title = A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold | journal = Discuss. Faraday. Soc. | volume = 11 | issue = | pages = 55–75 | doi=10.1039/df9511100055}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kimling J, Maier M, Okenve B, Kotaidis V, Ballot H, Plech A | title = Turkevich method for gold nanoparticle synthesis revisited | journal = The Journal of Physical Chemistry. B | volume = 110 | issue = 32 | pages = 15700–7 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16898714 | doi = 10.1021/jp061667w }}</ref> and refined by G. Frens in the 1970s,<ref name="G. Frens 1972">{{cite journal | last1 = Frens | first1 = G. | year = 1972 | title = Particle size and sol stability in metal colloids | journal = Colloid & Polymer Science | volume = 250 | issue = | pages = 736–741 | doi=10.1007/bf01498565}}</ref><ref name="G. Frens 1973">{{cite journal | last1 = Frens | first1 = G. | year = 1973 | title = Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspensions | journal = Nature | volume = 241 | issue = | pages = 20–22 | doi=10.1038/physci241020a0| bibcode = 1973NPhS..241...20F}}</ref> is the simplest one available. In general, it is used to produce modestly [[monodisperse]] spherical gold nanoparticles suspended in water of around 10–20 nm in diameter. Larger particles can be produced, but this comes at the cost of monodispersity and shape. It involves the reaction of small amounts of hot [[chloroauric acid]] with small amounts of [[sodium citrate]] solution. The colloidal gold will form because the citrate ions act as both a reducing agent and a capping agent. A capping agent is used in nanoparticle synthesis to stop particle growth and aggregation. A good capping agent has a high affinity for the new nuclei so it will bind to surface atoms which stabilizes the surface energy of the new nuclei and makes so that they cannot bind to other nuclei.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/cm4022479 | volume=26 | title=Removal and Utilization of Capping Agents in Nanocatalysis | year=2014 | journal=Chemistry of Materials | pages=72–83 | last1 = Niu | first1 = Zhiqiang | last2 = Li | first2 = Yadong | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

||

Recently, the evolution of the spherical gold nanoparticles in the Turkevich reaction has been elucidated. Extensive networks of gold nanowires are formed as a transient intermediate. These gold nanowires are responsible for the dark appearance of the reaction solution before it turns ruby-red.<ref name = "Pong, BK 2007">{{cite journal | |

Recently, the evolution of the spherical gold nanoparticles in the Turkevich reaction has been elucidated. Extensive networks of gold nanowires are formed as a transient intermediate. These gold nanowires are responsible for the dark appearance of the reaction solution before it turns ruby-red.<ref name = "Pong, BK 2007">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pong BK, Elim HI, Chong JX, Trout BL, Lee JY | year = 2007 | title = New Insights on the Nanoparticle Growth Mechanism in the Citrate Reduction of Gold(III) Salt: Formation of the Au Nanowire Intermediate and Its Nonlinear Optical Properties | journal = J. Phys. Chem. C | volume = 111 | issue = 17| pages = 6281–6287 | doi = 10.1021/jp068666o }}</ref> |

||

To produce larger particles, less sodium citrate should be added (possibly down to 0.05%, after which there simply would not be enough to reduce all the gold). The reduction in the amount of sodium citrate will reduce the amount of the citrate ions available for stabilizing the particles, and this will cause the small particles to aggregate into bigger ones (until the total surface area of all particles becomes small enough to be covered by the existing citrate ions). |

To produce larger particles, less sodium citrate should be added (possibly down to 0.05%, after which there simply would not be enough to reduce all the gold). The reduction in the amount of sodium citrate will reduce the amount of the citrate ions available for stabilizing the particles, and this will cause the small particles to aggregate into bigger ones (until the total surface area of all particles becomes small enough to be covered by the existing citrate ions). |

||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

=== Sonolysis === |

=== Sonolysis === |

||

Another method for the experimental generation of gold particles is by [[sonolysis]]. The first method of this type was invented by Baigent and Müller.<ref name="baigent">{{cite journal | |

Another method for the experimental generation of gold particles is by [[sonolysis]]. The first method of this type was invented by Baigent and Müller.<ref name="baigent">{{cite journal | vauthors = Baigent CL, Müller G | year = 1980 | title = A colloidal gold prepared using ultrasonics | journal = Experientia | volume = 36 | issue = 4| pages = 472–473 | doi=10.1007/BF01975154}}</ref> This work pioneered the use of ultrasound to provide the energy for the processes involved and allowed the creation of gold particles with a diameter of under 10 nm. In another method using ultrasound, the reaction of an aqueous solution of HAuCl<sub>4</sub> with [[glucose]],<ref>{{cite journal|year=2006|title=Sonochemical Formation of Single-Crystalline Gold Nanobelts|journal=Angew. Chem.|volume=118|issue=7|pages=1134–7|doi=10.1002/ange.200503762|author1=Jianling Zhang|author2=Jimin Du|author3=Buxing Han|author4=Zhimin Liu|author5=Tao Jiang|author6=Zhaofu Zhang}}</ref> the [[reducing agent]]s are hydroxyl radicals and sugar [[pyrolysis]] [[radical (chemistry)|radicals]] (forming at the interfacial region between the collapsing cavities and the bulk water) and the morphology obtained is that of nanoribbons with width 30–50 nm and length of several micrometers. These ribbons are very flexible and can bend with angles larger than 90°. When glucose is replaced by [[cyclodextrin]] (a glucose oligomer), only spherical gold particles are obtained, suggesting that glucose is essential in directing the morphology toward a ribbon. |

||

=== Block copolymer-mediated method === |

=== Block copolymer-mediated method === |

||

Revision as of 20:37, 26 September 2018

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

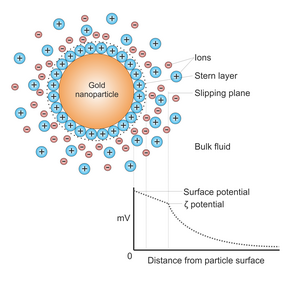

Colloidal gold is a sol or colloidal suspension of nanoparticles of gold in a fluid, usually water. The colloid is usually either an intense red colour (for spherical particles less than 100 nm) or blue/purple (for larger spherical particles or nanorods)[1]. Due to their optical, electronic, and molecular-recognition properties, gold nanoparticles are the subject of substantial research, with many potential or promised applications in a wide variety of areas, including electron microscopy, electronics, nanotechnology, materials science, and biomedicine.[2][3][4][5]

The properties of colloidal gold nanoparticles, and thus their applications, depend strongly upon their size and shape.[6] For example, rodlike particles have both transverse and longitudinal absorption peak, and anisotropy of the shape affects their self-assembly.[7]

History

Used since ancient times as a method of staining glass colloidal gold was used in the 4th-century Lycurgus Cup, which changes color depending on the location of light source.[8][9]

During the Middle Ages, soluble gold, a solution containing gold salt, had a reputation for its curative property for various diseases. In 1618, Francis Anthony, a philosopher and member of the medical profession, published a book called Panacea Aurea, sive tractatus duo de ipsius Auro Potabili[10] (Latin: gold potion, or two treatments of potable gold). The book introduces information on the formation of colloidal gold and its medical uses. About half a century later, English botanist Nicholas Culpepper published book in 1656, Treatise of Aurum Potabile,[11] solely discussing the medical uses of colloidal gold.

In 1676, Johann Kunckel, a German chemist, published a book on the manufacture of stained glass. In his book Valuable Observations or Remarks About the Fixed and Volatile Salts-Auro and Argento Potabile, Spiritu Mundi and the Like,[12] Kunckel assumed that the pink color of Aurum Potabile came from small particles of metallic gold, not visible to human eyes. In 1842, John Herschel invented a photographic process called chrysotype (from the Greek χρῡσός meaning "gold") that used colloidal gold to record images on paper.

Modern scientific evaluation of colloidal gold did not begin until Michael Faraday's work in the 1850s.[13][14] In 1856, in a basement laboratory of Royal Institution, Faraday accidentally created a ruby red solution while mounting pieces of gold leaf onto microscope slides.[15] Since he was already interested in the properties of light and matter, Faraday further investigated the optical properties of the colloidal gold. He prepared the first pure sample of colloidal gold, which he called 'activated gold', in 1857. He used phosphorus to reduce a solution of gold chloride. The colloidal gold Faraday made 150 years ago is still optically active. For a long time, the composition of the 'ruby' gold was unclear. Several chemists suspected it to be a gold tin compound, due to its preparation.[16][17] Faraday recognized that the color was actually due to the miniature size of the gold particles. He noted the light scattering properties of suspended gold microparticles, which is now called Faraday-Tyndall effect.[18]

In 1898, Richard Adolf Zsigmondy prepared the first colloidal gold in diluted solution.[19] Apart from Zsigmondy, Theodor Svedberg, who invented ultracentrifugation, and Gustav Mie, who provided the theory for scattering and absorption by spherical particles, were also interested in the synthesis and properties of colloidal gold.[7][20]

With advances in various analytical technologies in the 20th century, studies on gold nanoparticles has accelerated. Advanced microscopy methods, such as atomic force microscopy and electron microscopy, have contributed the most to nanoparticle research. Due to their comparably easy synthesis and high stability, various gold particles have been studied for their practical uses. Different types of gold nanoparticle are already used in many industries, such as medicine and electronics. For example, several FDA-approved nanoparticles are currently used in drug delivery.[21]

Physical properties

Optical

Colloidal gold has been used by artists for centuries because of the nanoparticle’s interactions with visible light. Gold nanoparticles absorb and scatter light[22] resulting in colours ranging from vibrant reds to blues to black and finally to clear and colorless, depending on particle size, shape, local refractive index, and aggregation state. These colors occur because of a phenomenon called Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), in which conduction electrons on the surface of the nanoparticle oscillate in resonance with incident light.

Effect of size

As a general rule, the wavelength of light absorbed increases as a function of increasing nano particle size.[23] For example, pseudo-spherical gold nanoparticles with diameters ~ 30 nm have a peak LSPR absorption at ~530 nm.[23][clarification needed]

Effect of local refractive index

Changes in the apparent color of a gold nanoparticle solution can also be caused by the environment in which the colloidal gold is suspended[24][25] The optical properties of gold nanoparticles depends on the refractive index near the nanoparticle surface, therefore both the molecules directly attached to the nanoparticle surface (i.e. nanoparticle ligands) and/or the nanoparticle solvent both may influence observed optical features.[24] As the refractive index near the gold surface increases, the NP LSPR will shift to longer wavelengths[25] In addition to solvent environment, the extinction peak can be tuned by coating the nanoparticles with non-conducting shells such as silica, bio molecules, or aluminium oxide.[26]

Effect of aggregation

When gold nano particles aggregate, the optical properties of the particle change, because the effective particle size, shape, and dielectric environment all change.[27]

Medical research

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (August 2017) |  |

Electron microscopy

Colloidal gold and various derivatives have long been among the most widely used labels for antigens in biological electron microscopy.[28][29][30][31][32] Colloidal gold particles can be attached to many traditional biological probes such as antibodies, lectins, superantigens, glycans, nucleic acids,[33] and receptors. Particles of different sizes are easily distinguishable in electron micrographs, allowing simultaneous multiple-labelling experiments.[34]

In addition to biological probes, gold nanoparticles can be transferred to various mineral substrates, such as mica, single crystal silicon, and atomically flat gold(III), to be observed under atomic force microscopy (AFM).[35]

Drug delivery system

Gold nanoparticles can be used to optimize the biodistribution of drugs to diseased organs, tissues or cells, in order to improve and target drug delivery.[36][37] Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery is feasible only if the drug distribution is otherwise inadequate. These cases include drug targeting of unstable (proteins, siRNA, DNA), delivery to the difficult sites (brain, retina, tumors, intracellular organelles) and drugs with serious side effects (e.g. anti-cancer agents). The performance of the nanoparticles depends on the size and surface functionalities in the particles. Also, the drug release and particle disintegration can vary depending on the system (e.g. biodegradable polymers sensitive to pH). An optimal nanodrug delivery system ensures that the active drug is available at the site of action for the correct time and duration, and their concentration should be above the minimal effective concentration (MEC) and below the minimal toxic concentration (MTC).[38]

Gold nanoparticles are being investigated as carriers for drugs such as Paclitaxel.[39] The administration of hydrophobic drugs require molecular encapsulation and it is found that nanosized particles are particularly efficient in evading the reticuloendothelial system.

Tumor detection

In cancer research, colloidal gold can be used to target tumors and provide detection using SERS (surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy) in vivo. These gold nanoparticles are surrounded with Raman reporters, which provide light emission that is over 200 times brighter than quantum dots. It was found that the Raman reporters were stabilized when the nanoparticles were encapsulated with a thiol-modified polyethylene glycol coat. This allows for compatibility and circulation in vivo. To specifically target tumor cells, the polyethylenegylated gold particles are conjugated with an antibody (or an antibody fragment such as scFv), against, e.g. epidermal growth factor receptor, which is sometimes overexpressed in cells of certain cancer types. Using SERS, these pegylated gold nanoparticles can then detect the location of the tumor.[40]

Gold nanoparticles accumulate in tumors, due to the leakiness of tumor vasculature, and can be used as contrast agents for enhanced imaging in a time-resolved optical tomography system using short-pulse lasers for skin cancer detection in mouse model. It is found that intravenously administrated spherical gold nanoparticles broadened the temporal profile of reflected optical signals and enhanced the contrast between surrounding normal tissue and tumors.[41]

Gene therapy

Gold nanoparticles have shown potential as intracellular delivery vehicles for siRNA oligonucleotides with maximal therapeutic impact.

Gold nanoparticles show potential as intracellular delivery vehicles for antisense oligonucleotides (ssDNA,dsDNA) by providing protection against intracellular nucleases and ease of functionalization for selective targeting.[42]

Photothermal agents

Gold nanorods are being investigated as photothermal agents for in-vivo applications. Gold nanorods are rod-shaped gold nanoparticles whose aspect ratios tune the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band from the visible to near-infrared wavelength. The total extinction of light at the SPR is made up of both absorption and scattering. For the smaller axial diameter nanorods (~10 nm), absorption dominates, whereas for the larger axial diameter nanorods (>35 nm) scattering can dominate. As a consequence, for in-vivo applications, small diameter gold nanorods are being used as photothermal converters of near-infrared light due to their high absorption cross-sections.[43] Since near-infrared light transmits readily through human skin and tissue, these nanorods can be used as ablation components for cancer, and other targets. When coated with polymers, gold nanorods have been observed to circulate in-vivo with half-lives longer than 6 hours, bodily residence times around 72 hours, and little to no uptake in any internal organs except the liver.[44] Apart from rod-like gold nanoparticles, also spherical colloidal gold nanoparticles are recently used as markers in combination with photothermal single particle microscopy.

Radiotherapy dose enhancer

Considerable interest has been shown in the use of gold and other heavy-atom-containing nanoparticles to enhance the dose delivered to tumors.[45] Since the gold nanoparticles are taken up by the tumors more than the nearby healthy tissue, the dose is selectively enhanced. The biological effectiveness of this type of therapy seems to be due to the local deposition of the radiation dose near the nanoparticles.[46] This mechanism is the same as occurs in heavy ion therapy.

Detection of toxic gas

Researchers have developed simple inexpensive methods for on-site detection of hydrogen sulfide H

2S present in air based on the antiaggregation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Dissolving H

2S into a weak alkaline buffer solution leads to the formation of HS-, which can stabilize AuNPs and ensure they maintain their red color allowing for visual detection of toxic levels of H

2S.[47]

Gold nanoparticle based biosensor

Gold nanoparticles are incorporated into biosensors to enhance its stability, sensitivity, and selectivity.[48] Nanoparticle properties such as small size, high surface-to-volume ratio, and high surface energy allow immobilization of large range of biomolecules. Gold nanoparticle, in particular, could also act as "electron wire" to transport electrons and its amplification effect on electromagnetic light allows it to function as signal amplifiers.[49][50] Main types of gold nanoparticle based biosensors are optical and electrochemical biosensor.

Optical biosensor