Surface epithelial-stromal tumor: Difference between revisions

m Fix PMC warnings |

consistent citation formatting; templated cites; combined repeated citations |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| deaths = |

| deaths = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Surface epithelial-stromal tumors''' are a class of [[Ovarian cancer|ovarian neoplasm]]s that may be [[benign]] or [[malignant]]. [[Neoplasm]]s in this group are thought to be derived from the [[ovarian surface epithelium]] (modified [[peritoneum]]) or from [[:wikt:ectopic|ectopic]] [[endometrial]] or [[Fallopian tube]] (tubal) tissue. Tumors of this type are also called '''ovarian adenocarcinoma'''.<ref name=SEER6215ch16>{{Cite book| |

'''Surface epithelial-stromal tumors''' are a class of [[Ovarian cancer|ovarian neoplasm]]s that may be [[benign]] or [[malignant]]. [[Neoplasm]]s in this group are thought to be derived from the [[ovarian surface epithelium]] (modified [[peritoneum]]) or from [[:wikt:ectopic|ectopic]] [[endometrial]] or [[Fallopian tube]] (tubal) tissue. Tumors of this type are also called '''ovarian adenocarcinoma'''.<ref name=SEER6215ch16>{{Cite book| chapter = Chapter 16: Cancers of the Ovary | vauthors = Kosary CL |pages=133–144|publisher=National Cancer Institute|title=SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: US SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics| veditors = Baguio RN, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner MJ |series=SEER Program |volume=NIH Pub. No. 07-6215 | location =Bethesda, MD |year=2007 |chapter-url= http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/survival/surv_ovary.pdf |url=http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/survival/ }}</ref> This group of tumors accounts for 90% to 95% of all cases of [[ovarian cancer]].<ref>{{cite book |author1=Bradshaw, Karen D. |author2=Schorge, John O. |author3=Schaffer, Joseph |author4=Lisa M. Halvorson |author5=Hoffman, Barbara G. |title=Williams' Gynecology |publisher=McGraw-Hill Professional |location= |year=2008 |pages= |isbn=978-0-07-147257-9 |oclc= |doi= |access-date=}}</ref> Serum [[CA-125]] is often elevated but is only 50% accurate so it is not a useful tumor marker to assess the progress of treatment. |

||

{{TOC limit}} |

{{TOC limit}} |

||

==Classification== |

==Classification== |

||

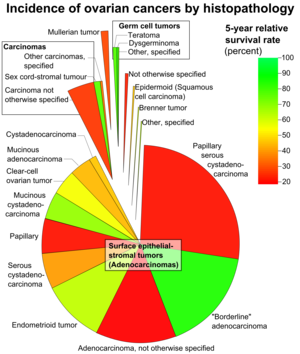

[[File:Incidence of ovarian cancers by histopathology.png|thumb|300px|Ovarian cancers in women aged 20+, with area representing relative incidence and color representing [[5-year relative survival rate]].<ref name=SEER6215ch16 |

[[File:Incidence of ovarian cancers by histopathology.png|thumb|300px|Ovarian cancers in women aged 20+, with area representing relative incidence and color representing [[5-year relative survival rate]].<ref name=SEER6215ch16 /> ''Surface epithelial-stromal tumors'' are labeled in center of the main diagram, and represent all types except the ones separated at top.]] |

||

Epithelial-stromal tumors are classified on the basis of the [[epithelial cell]] type, the relative amounts of epithelium and [[Stroma of ovary|stroma]], the presence of [[wiktionary:Papillary|papillary]] processes, and the location of the epithelial elements. [[Microscope|Microscopic]] [[pathology|pathological]] features determine whether a surface epithelial-stromal tumor is [[benign]], [[Ovarian cancer|borderline]], or [[malignant]] (evidence of malignancy and stromal invasion). Borderline tumors are of uncertain malignant potential. |

Epithelial-stromal tumors are classified on the basis of the [[epithelial cell]] type, the relative amounts of epithelium and [[Stroma of ovary|stroma]], the presence of [[wiktionary:Papillary|papillary]] processes, and the location of the epithelial elements. [[Microscope|Microscopic]] [[pathology|pathological]] features determine whether a surface epithelial-stromal tumor is [[benign]], [[Ovarian cancer|borderline]], or [[malignant]] (evidence of malignancy and stromal invasion). Borderline tumors are of uncertain malignant potential. |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

===Small cell tumors=== |

===Small cell tumors=== |

||

[http://www.sc-ovca.org/ Small cell ovarian cancer (SCCO)] are generally classified into epithelial tumors<ref>[http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Tumors/OvaryEpithTumID5230.html Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology - Ovary: Epithelial tumors]. Retrieved June 2014. By Lee-Jones, L. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 2004;8(2):115-133.</ref> associated with distinctive endocrine features.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Small Cell and Neuroendocrine Cancers of the Ovary|last=Kaphan|first=Ariel A.|last2=Castro|first2=Cesar M.|date=2014-01-01|publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd|isbn=9781118655344|editor-last=MPH|editor-first=rcela G. del Carmen MD|pages=139–147|language=en|doi=10.1002/9781118655344.ch12|editor-last2=FRCPATH|editor-first2=Robert H. Young MD|editor-last3=MD|editor-first3=John O. Schorge|editor-last4=MD|editor-first4=Michael J. Birrer}}</ref> |

[http://www.sc-ovca.org/ Small cell ovarian cancer (SCCO)] are generally classified into epithelial tumors<ref>[http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Tumors/OvaryEpithTumID5230.html Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology - Ovary: Epithelial tumors]. Retrieved June 2014. By Lee-Jones, L. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 2004;8(2):115-133.</ref> associated with distinctive endocrine features.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Small Cell and Neuroendocrine Cancers of the Ovary|last=Kaphan|first=Ariel A.|last2=Castro|first2=Cesar M. | name-list-format = vanc |date=2014-01-01|publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd|isbn=9781118655344|editor-last=MPH|editor-first=rcela G. del Carmen MD |pages=139–147 |language=en |doi=10.1002/9781118655344.ch12 |editor-last2=FRCPATH|editor-first2=Robert H. Young MD|editor-last3=MD|editor-first3=John O. Schorge|editor-last4=MD|editor-first4=Michael J. Birrer}}</ref> |

||

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises SCCO as two distinct entities: [http://www.sc-ovca.org/ Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Hypercalcemic Type ( SCCOHT)] and Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Pulmonary Type ( SCCOPT).<ref name=":0" /> |

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises SCCO as two distinct entities: [http://www.sc-ovca.org/ Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Hypercalcemic Type ( SCCOHT)] and Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Pulmonary Type ( SCCOPT).<ref name=":0" /> |

||

Small cell tumours are rare and aggressive, they contribute to less than 2% of all gynaecologic malignancies.<ref name=":0" /> The average age of diagnosis is 24 years old, and the majority of patients also present with hypercalcemia (62%).<ref name="BakhruLiu2012">{{cite journal| |

Small cell tumours are rare and aggressive, they contribute to less than 2% of all gynaecologic malignancies.<ref name=":0" /> The average age of diagnosis is 24 years old, and the majority of patients also present with hypercalcemia (62%).<ref name="BakhruLiu2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bakhru A, Liu JR, Lagstein A | title = A case of small cell carcinoma of the ovary hypercalcemic variant in a teenager | journal = Gynecologic Oncology Case Reports | volume = 2 | issue = 4 | pages = 139–42 | year = 2012 | pmid = 24371647 | pmc = 3861231 | doi = 10.1016/j.gynor.2012.09.001 }}</ref> It typically present with a unilateral large tumor.<ref name="BakhruLiu2012" /> Most women die within a year of diagnosis.<ref name="BakhruLiu2012" /> |

||

==Treatment== |

==Treatment== |

||

For more general information, see [[ovarian cancer]]. |

For more general information, see [[ovarian cancer]]. |

||

Research suggests that in the first line treatment of Endometrial Ovarian Cancer (EOC), Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin paired with Carboplatin is a satisfactory alternative to Paclitaxel with Carboplatin.<ref>{{ |

Research suggests that in the first line treatment of Endometrial Ovarian Cancer (EOC), Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin paired with Carboplatin is a satisfactory alternative to Paclitaxel with Carboplatin.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lawrie TA, Rabbie R, Thoma C, Morrison J | title = Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for first-line treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 10 | pages = CD010482 | date = October 2013 | pmid = 24142521 | pmc = 6457824 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.cd010482.pub2 | url = http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010482 | publisher = John Wiley & Sons, Ltd | collaboration = The Cochrane Collaboration | veditors = Lawrie TA }}</ref> In people with platinum-sensitive relapsed EOC, research has found that Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin with Carboplatin is a better treatment than Paclitaxel with Carboplatin.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lawrie TA, Bryant A, Cameron A, Gray E, Morrison J | title = Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 7 | pages = CD006910 | date = July 2013 | pmid = 23835762 | pmc = 6457816 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.cd006910.pub2 }}</ref> |

||

For advanced cancer of this histology, the US [[National Cancer Institute]] recommends a method of [[chemotherapy]] that combines [[intravenous]] (IV) and [[intraperitoneal]] (IP) administration.<ref> |

For advanced cancer of this histology, the US [[National Cancer Institute]] recommends a method of [[chemotherapy]] that combines [[intravenous]] (IV) and [[intraperitoneal]] (IP) administration.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/IPchemotherapyrelease | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090113184800/http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/pressreleases/IPchemotherapyrelease | archive-date = 9 January 2009 | title = NCI Issues Clinical Announcement for Preferred Method of Treatment for Advanced Ovarian Cancer | date = January 2006 | work = National Cancer Institute }}</ref> Preferred [[chemotherapeutic agent]]s include a [[platinum]] drug with a [[taxane]]. |

||

==Metastases== |

==Metastases== |

||

For surface epithelial-stromal tumors, the most common sites of [[metastasis]] are the [[pleural cavity]] (33%), the [[liver]] (26%), and the [[lung]]s (3%).<ref |

For surface epithelial-stromal tumors, the most common sites of [[metastasis]] are the [[pleural cavity]] (33%), the [[liver]] (26%), and the [[lung]]s (3%).<ref name="pmid11844820">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kolomainen DF, Larkin JM, Badran M, A'Hern RP, King DM, Fisher C, Bridges JE, Blake PR, Barton DP, Shepherd JH, Kaye SB, Gore ME | display-authors = 6 | title = Epithelial ovarian cancer metastasizing to the brain: a late manifestation of the disease with an increasing incidence | journal = Journal of Clinical Oncology | volume = 20 | issue = 4 | pages = 982–6 | date = February 2002 | pmid = 11844820 | doi = 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.982 }}</ref> |

||

==Effect on fertility== |

==Effect on fertility== |

||

[[Female infertility|Fertility]] subsequent to treatment of surface epithelial-stromal tumors depends mainly on histology and initial |

[[Female infertility|Fertility]] subsequent to treatment of surface epithelial-stromal tumors depends mainly on histology and initial |

||

staging to separate it into early borderline (or more benign) versus advanced stages of borderline (or more malignant).<ref name=darai2013>{{ |

staging to separate it into early borderline (or more benign) versus advanced stages of borderline (or more malignant).<ref name=darai2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Daraï E, Fauvet R, Uzan C, Gouy S, Duvillard P, Morice P | title = Fertility and borderline ovarian tumor: a systematic review of conservative management, risk of recurrence and alternative options | journal = Human Reproduction Update | volume = 19 | issue = 2 | pages = 151–66 | year = 2012 | pmid = 23242913 | pmc = | doi = 10.1093/humupd/dms047 }}</ref> Conservative management (without bilateral [[oophorectomy]]) of early stage borderline tumors have been estimated to result in chance of over 50% of spontaneous pregnancy with a low risk of lethal recurrence of the tumor (0.5%).<ref name=darai2013/> On the other hand, in cases of conservative treatment in advanced stage borderline tumors, spontaneous pregnancy rates have been estimated to be 35% and the risk of lethal recurrence 2%.<ref name=darai2013/> |

||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

*{{cite book |author=Braunwald, Eugene |title=Harrison's principles of internal medicine |publisher=McGraw-Hill |location=New York |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-07-913686-2 |edition=15th|title-link=Harrison's principles of internal medicine }} |

* {{cite book |author=Braunwald, Eugene |title=Harrison's principles of internal medicine |publisher=McGraw-Hill |location=New York |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-07-913686-2 |edition=15th|title-link=Harrison's principles of internal medicine }} |

||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

Revision as of 07:22, 13 March 2020

| Surface epithelial-stromal tumor | |

|---|---|

| |

| High magnification micrograph of a Brenner tumor, a type of surface epithelial-stromal tumor. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Surface epithelial-stromal tumors are a class of ovarian neoplasms that may be benign or malignant. Neoplasms in this group are thought to be derived from the ovarian surface epithelium (modified peritoneum) or from ectopic endometrial or Fallopian tube (tubal) tissue. Tumors of this type are also called ovarian adenocarcinoma.[1] This group of tumors accounts for 90% to 95% of all cases of ovarian cancer.[2] Serum CA-125 is often elevated but is only 50% accurate so it is not a useful tumor marker to assess the progress of treatment.

Classification

Epithelial-stromal tumors are classified on the basis of the epithelial cell type, the relative amounts of epithelium and stroma, the presence of papillary processes, and the location of the epithelial elements. Microscopic pathological features determine whether a surface epithelial-stromal tumor is benign, borderline, or malignant (evidence of malignancy and stromal invasion). Borderline tumors are of uncertain malignant potential.

This group consists of serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, and brenner (transitional cell) tumors, though there are a few mixed, undifferentiated and unclassified types.

Serous tumors

- These tumors vary in size from small and nearly imperceptible to large, filling the abdominal cavity.

- Benign, borderline, and malignant types of serous tumors account for about 30% of all ovarian tumors.

- 75% are benign or of borderline malignancy, and 25% are malignant

- The malignant form of this tumor, serous cystadenocarcinoma, accounts for approximately 40% of all carcinomas of the ovary and are the most common malignant ovarian tumors.

- Benign and borderline tumors are most common between the ages of 20 and 50 years.

- Malignant serous tumors occur later in life on average, although somewhat earlier in familial cases.

- 20% of benign, 30% of borderline, and 66% of malignant tumors are bilateral (affect both ovaries).

Components can include:

- cystic areas

- cystic and fibrous areas

- predominantly fibrous areas

The chance of malignancy of the tumor increases with the amount of solid areas present, including both papillary structures and any necrotic tissue present.

Pathology

- lined by tall, columnar, ciliated epithelial cells

- filled with clear serous fluid

- the term serous which originated as a description of the cyst fluid has come to be describe the particular type of epithelial cell seen in these tumors

- may involve the surface of the ovary

- the division between benign, borderline, and malignant is ascertained by assessing:

- cellular atypia (whether or not individual cells look abnormal)

- invasion of surrounding ovarian stroma (whether or not cells are infiltrating surrounding tissue)

- borderline tumors may have cellular atypia but do NOT have evidence of invasion

- the presence of psammoma bodies are a characteristic microscopic finding of cystadenocarcinomas[3]

Prognosis

The prognosis of a serous tumor, like most neoplasms, depends on

- degree of differentiation

- this is how closely the tumor cells resemble benign cells

- a well-differentiated tumor closely resembles benign tumors

- a poorly differentiated tumor may not resemble the cell type of origin at all

- a moderately differentiated tumor usually resembles the cell type of origin, but appears frankly malignant

- extension of tumor to other structures

- in particular with serous malignancies, the presence of malignant spread to the peritoneum is important with regard to prognosis.

The five year survival rate of borderline and malignant tumors confined to the ovaries are 100% and 70% respectively. If the peritoneum is involved, these rates become 90% and 25%.

While the 5-year survival rates of borderline tumors are excellent, this should not be seen as evidence of cure, as recurrences can occur many years later.

Mucinous tumors

- Closely resemble their serous counterparts but unlikely to be bilateral

- Somewhat less common, accounting for about 25% of all ovarian neoplasms

- In some cases mucinous tumors are characterized by more cysts of variable size and a rarity of surface involvement as compared to serous tumors

- Also in comparison to serous tumors, mucinous tumors are less frequently bilateral, approximately 5% of primary mucinous tumors are bilateral.

- May form very large cystic masses, with recorded weights exceeding 25 kg

Pathology

Mucinous tumors are characterized by a lining of tall columnar epithelial cells with apical mucin and the absence of cilia, similar in appearance with benign cervical or intestinal epithelia. The appearance can look similar to colonic or ovarian cancer, but typically originates from the appendix (see mucinous adenocarcinoma with clinical condition Pseudomyxoma peritonei). Clear stromal invasion is used to differentiate borderline tumors from malignant tumors.

Prognosis

10-year survival rates for borderline tumors contained within the ovary, malignant tumors without invasion, and invasive malignant tumors are greater than 95%, 90%, and 66%, respectively. One rare but noteworthy condition associated with mucinous ovarian neoplasms is pseudomyxoma peritonei. As primary ovarian mucinous tumors are usually unilateral (in one ovary), the presentation of bilateral mucinous tumors requires exclusion of a non-ovarian origin, usually the appendix.

Endometrioid tumors

Endometrioid tumors account for approximately 20% of all ovarian cancers and are mostly malignant (endometroid carcinomas). They are made of tubular glands bearing a close resemblance to benign or malignant endometrium. 15-30% of endometrioid carcinomas occur in individuals with carcinoma of the endometrium, and these patients have a better prognosis. They appear similar to other surface epithelial-stromal tumors, with solid and cystic areas. 40% of these tumors are bilateral, when bilateral, metastases is often present.

Pathology

- Glands bearing a strong resemblance to endometrial-type glands

- Benign tumors have mature-appearing glands in a fibrous stroma

- Borderline tumors have a complex branching pattern without stromal invasion

- Carcinomas (malignant tumors) have invasive glands with crowded, atypical cells, frequent mitoses. With poorer differentiation, the tumor becomes more solid.

Prognosis

Prognosis again is dependent on the spread of the tumor, as well as how differentiated the tumor appears. The overall prognosis is somewhat worse than for serous or mucinous tumors, and the 5-year survival rate for patients with tumors confined to the ovary is approximately 75%.

Clear cell tumors

Clear cell tumors are characterized by large epithelial cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and may be seen in association with endometriosis or endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary, bearing a resemblance to clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium. They may be predominantly solid or cystic. If solid, the clear cells tend to be arranged in sheets or tubules. In the cystic variety, the neoplastic cells make up the cyst lining.

Prognosis

These tumors tend to be aggressive, the five year survival rate for tumors confined to the ovaries is approximately 65%. If the tumor has spread beyond the ovary at diagnosis, the prognosis is poor

Brenner tumor

Brenner tumors are uncommon surface-epithelial stromal cell tumors in which the epithelial cell (which defines these tumors) is a transitional cell. These are similar in appearance to bladder epithelia. The tumors may be very small to very large, and may be solid or cystic. Histologically, the tumor consists of nests of the aforementioned transitional cells within surrounding tissue that resembles normal ovary. Brenner tumors may be benign or malignant, depending on whether the tumor cells invade the surrounding tissue.

Small cell tumors

Small cell ovarian cancer (SCCO) are generally classified into epithelial tumors[4] associated with distinctive endocrine features.[5]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recognises SCCO as two distinct entities: Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Hypercalcemic Type ( SCCOHT) and Small Cell Ovarian Cancer of Pulmonary Type ( SCCOPT).[5]

Small cell tumours are rare and aggressive, they contribute to less than 2% of all gynaecologic malignancies.[5] The average age of diagnosis is 24 years old, and the majority of patients also present with hypercalcemia (62%).[6] It typically present with a unilateral large tumor.[6] Most women die within a year of diagnosis.[6]

Treatment

For more general information, see ovarian cancer.

Research suggests that in the first line treatment of Endometrial Ovarian Cancer (EOC), Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin paired with Carboplatin is a satisfactory alternative to Paclitaxel with Carboplatin.[7] In people with platinum-sensitive relapsed EOC, research has found that Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin with Carboplatin is a better treatment than Paclitaxel with Carboplatin.[8]

For advanced cancer of this histology, the US National Cancer Institute recommends a method of chemotherapy that combines intravenous (IV) and intraperitoneal (IP) administration.[9] Preferred chemotherapeutic agents include a platinum drug with a taxane.

Metastases

For surface epithelial-stromal tumors, the most common sites of metastasis are the pleural cavity (33%), the liver (26%), and the lungs (3%).[10]

Effect on fertility

Fertility subsequent to treatment of surface epithelial-stromal tumors depends mainly on histology and initial staging to separate it into early borderline (or more benign) versus advanced stages of borderline (or more malignant).[11] Conservative management (without bilateral oophorectomy) of early stage borderline tumors have been estimated to result in chance of over 50% of spontaneous pregnancy with a low risk of lethal recurrence of the tumor (0.5%).[11] On the other hand, in cases of conservative treatment in advanced stage borderline tumors, spontaneous pregnancy rates have been estimated to be 35% and the risk of lethal recurrence 2%.[11]

References

- ^ a b Kosary CL (2007). "Chapter 16: Cancers of the Ovary" (PDF). In Baguio RN, Young JL, Keel GE, Eisner MP, Lin YD, Horner MJ (eds.). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: US SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. SEER Program. Vol. NIH Pub. No. 07-6215. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. pp. 133–144.

- ^ Bradshaw, Karen D.; Schorge, John O.; Schaffer, Joseph; Lisa M. Halvorson; Hoffman, Barbara G. (2008). Williams' Gynecology. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

- ^ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ^ Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology - Ovary: Epithelial tumors. Retrieved June 2014. By Lee-Jones, L. Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 2004;8(2):115-133.

- ^ a b c Kaphan, Ariel A.; Castro, Cesar M. (2014-01-01). MPH, rcela G. del Carmen MD; FRCPATH, Robert H. Young MD; MD, John O. Schorge; MD, Michael J. Birrer (eds.). Small Cell and Neuroendocrine Cancers of the Ovary. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 139–147. doi:10.1002/9781118655344.ch12. ISBN 9781118655344.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Bakhru A, Liu JR, Lagstein A (2012). "A case of small cell carcinoma of the ovary hypercalcemic variant in a teenager". Gynecologic Oncology Case Reports. 2 (4): 139–42. doi:10.1016/j.gynor.2012.09.001. PMC 3861231. PMID 24371647.

- ^ Lawrie TA, Rabbie R, Thoma C, Morrison J, et al. (The Cochrane Collaboration) (October 2013). Lawrie TA (ed.). "Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for first-line treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: CD010482. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010482.pub2. PMC 6457824. PMID 24142521.

- ^ Lawrie TA, Bryant A, Cameron A, Gray E, Morrison J (July 2013). "Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD006910. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006910.pub2. PMC 6457816. PMID 23835762.

- ^ "NCI Issues Clinical Announcement for Preferred Method of Treatment for Advanced Ovarian Cancer". National Cancer Institute. January 2006. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 13 January 2009 suggested (help) - ^ Kolomainen DF, Larkin JM, Badran M, A'Hern RP, King DM, Fisher C, et al. (February 2002). "Epithelial ovarian cancer metastasizing to the brain: a late manifestation of the disease with an increasing incidence". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 20 (4): 982–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.982. PMID 11844820.

- ^ a b c Daraï E, Fauvet R, Uzan C, Gouy S, Duvillard P, Morice P (2012). "Fertility and borderline ovarian tumor: a systematic review of conservative management, risk of recurrence and alternative options". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (2): 151–66. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms047. PMID 23242913.

Sources

- Braunwald, Eugene (2001). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-913686-2.