Ostafrikasaurus: Difference between revisions

Some ce and more on Tendaguru palaeofauna |

|||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

During the time of the [[German colonial empire]], the [[Museum fur Naturkunde|Museum für Naturkunde]] (Natural History Museum) of Berlin arranged an expedition in [[German East Africa]] (now [[Tanzania]]) that took place from 1909 to 1912, and is now regarded by scientists as one of the largest expeditions in palaeontological history. Most of the excavations were situated in the southeastern [[Tendaguru Formation]], a [[fossil]]-rich site part of the [[Mandawa Basin]] dated to the [[Late Jurassic]] [[Period (geology)|Period]].<ref name=":02">{{Cite journal|last=Tamborini|first=Marco|last2=Vennen|first2=Mareike|date=2017-06-05|title=Disruptions and changing habits: The case of the Tendaguru expedition|journal=Museum History Journal|language=en|volume=10|issue=2|pages=183–199|doi=10.1080/19369816.2017.1328872|issn=1936-9816}}</ref><ref name=":22">{{Cite journal|last=Bussert|first=Robert|last2=Heinrich|first2=Wolf-Dieter|last3=Aberhan|first3=Martin|date=2009-08-01|title=The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230014275|journal=Fossil Record|volume=12|issue=2|pages=141–174|doi=10.1002/mmng.200900004}}</ref> Among the many [[dinosaur]] fossils retrieved from the dig sites were 230 specimens of [[Theropoda|theropod]] teeth.<ref name=":1" /> One of these was an isolated tooth catalogued as MB R 1084, found either nearby or atop Tendaguru Hill at the Upper Dinosaur [[Member (geology)|Member]].<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2">{{cite journal|last=Buffetaut|first=Eric|year=2012|title=An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition|url=http://www.dinosauria.org/documents/2017/buffetaut_2013.pdf|journal=Oryctos|volume=10|issue=|pages=1–8|via=}}</ref> It was originally attributed to the [[species]] ''[[Labrosaurus]]''? ''stechowi'' in 1920 by German [[palaeontologist]] [[Werner Janensch]], based on comparable ornamentation to a tooth described as ''Labrosaurus'' ''sulcatus'' by [[Othniel Charles Marsh]].<ref name=":1">W. Janensch, 1920, "Ueber ''Elaphrosaurus bambergi'' und die Megalosaurier aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", ''Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin'' '''1920''': 225-235</ref> A detailed [[monograph]] by Janensch published in 1925 assigned MB R 1084, as well as eight teeth from the Middle Dinosaur Member to ''L.''? ''stechowi'' and divided them into five [[Morphotype|morphotypes]] (from a to e).<ref>Janensch, W., 1925, "Die Coelurosaurier und Theropoden der Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", ''Palaeontographica'' Supplement 7: 1–99</ref> |

During the time of the [[German colonial empire]], the [[Museum fur Naturkunde|Museum für Naturkunde]] (Natural History Museum) of Berlin arranged an expedition in [[German East Africa]] (now [[Tanzania]]) that took place from 1909 to 1912, and is now regarded by scientists as one of the largest expeditions in palaeontological history. Most of the excavations were situated in the southeastern [[Tendaguru Formation]], a [[fossil]]-rich site part of the [[Mandawa Basin]] dated to the [[Late Jurassic]] [[Period (geology)|Period]].<ref name=":02">{{Cite journal|last=Tamborini|first=Marco|last2=Vennen|first2=Mareike|date=2017-06-05|title=Disruptions and changing habits: The case of the Tendaguru expedition|journal=Museum History Journal|language=en|volume=10|issue=2|pages=183–199|doi=10.1080/19369816.2017.1328872|issn=1936-9816}}</ref><ref name=":22">{{Cite journal|last=Bussert|first=Robert|last2=Heinrich|first2=Wolf-Dieter|last3=Aberhan|first3=Martin|date=2009-08-01|title=The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230014275|journal=Fossil Record|volume=12|issue=2|pages=141–174|doi=10.1002/mmng.200900004}}</ref> Among the many [[dinosaur]] fossils retrieved from the dig sites were 230 specimens of [[Theropoda|theropod]] teeth.<ref name=":1" /> One of these was an isolated tooth catalogued as MB R 1084, found either nearby or atop Tendaguru Hill at the Upper Dinosaur [[Member (geology)|Member]].<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2">{{cite journal|last=Buffetaut|first=Eric|year=2012|title=An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition|url=http://www.dinosauria.org/documents/2017/buffetaut_2013.pdf|journal=Oryctos|volume=10|issue=|pages=1–8|via=}}</ref> It was originally attributed to the [[species]] ''[[Labrosaurus]]''? ''stechowi'' in 1920 by German [[palaeontologist]] [[Werner Janensch]], based on comparable ornamentation to a tooth described as ''Labrosaurus'' ''sulcatus'' by [[Othniel Charles Marsh]].<ref name=":1">W. Janensch, 1920, "Ueber ''Elaphrosaurus bambergi'' und die Megalosaurier aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", ''Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin'' '''1920''': 225-235</ref> A detailed [[monograph]] by Janensch published in 1925 assigned MB R 1084, as well as eight teeth from the Middle Dinosaur Member to ''L.''? ''stechowi'' and divided them into five [[Morphotype|morphotypes]] (from a to e).<ref>Janensch, W., 1925, "Die Coelurosaurier und Theropoden der Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", ''Palaeontographica'' Supplement 7: 1–99</ref> |

||

In 2000, American palaeontologists James Madsen and Samuel Welles referred the ''L.''? ''stechowi'' teeth to ''[[Ceratosaurus]] sp.'' (of uncertain species), because they resembled teeth from the [[Glossary of dinosaur anatomy#premaxilla|premaxilla]] and [[Glossary of dinosaur anatomy#dentary|dentary]] jaw bones of ''Ceratosaurus'', a theropod from the North American [[Morrison Formation]].<ref name="MW00" /> In 2007, American palaeontologist Denver Fowler instead proposed that the teeth were those of a [[Spinosauridae|spinosaurid]] dinosaur similar to ''[[Baryonyx]]'', which would make it among the oldest known spinosaurid fossils and thus some of the earliest evidence of the group.<ref name="Fowler2007">{{cite journal|last1=Fowler|first1=D. W.|date=2007|title=Recently rediscovered baryonychine teeth (Dinosauria: Theropoda): New morphologic data, range extension & similarity to ''Ceratosaurus''|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271217531|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=27|issue=3|pages=3}}</ref> This analysis was maintained by French palaeontologist [[Eric Buffetaut]], who examined the teeth that year, and in a 2008 paper referred specimen MB R 1084 to the Spinosauridae. Bufetaut found that this specimen differed from other teeth previously referred to ''L.''? ''stechowi'', and that another isolated tooth (MB R 1091) from the Middle Dinosaur Member might represent the same animal.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Buffetaut|first=Eric|date=2008|title=Spinosaurid teeth from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania, with remarks on the evolutionary and biogeographical history of the Spinosauridae|url=https://www.academia.edu/3101178|journal=Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon|language=en|volume=164|pages=26–28|via=}}</ref> He also questioned Janensch's provisional assignment of the teeth to the dubious [[genus]] ''Labrosaurus'', which was based on scant remains from the Morrison Formation that were later attributed to ''[[Allosaurus]].''<ref name=":0" />''<ref name="HMC042">{{cite book|last=Holtz|first=Thomas R., Jr.|title=The Dinosauria|author2=Molnar, Ralph E.|author3=Currie, Philip J.|publisher=University of California Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-520-24209-8|editor=Weishampel David B.|edition=2nd|location=Berkeley|pages=71–110|chapter=Basal Tetanurae|authorlink=Thomas R. Holtz, Jr.|editor2=Dodson, Peter|editor3=Osmólska, Halszka}}</ref>'' Furthermore, Buffetaut noted that the ''L''. ''sulcatus'' tooth illustrated by Marsh is now regarded as belonging to ''Ceratosaurus''.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> Similarly, ''L''. ''stechowi'' has been relegated as a [[Dubious name|dubious]] [[Ceratosauria|ceratosaurian]] related to ''Ceratosaurus''.<ref name="MW00">{{cite book|last=Madsen|first=James H.|title=Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda), a Revised Osteology|author2=Welles, Samuel P.|publisher=Utah Geological Survey|year=2000|series=Miscellaneous Publication, '''00-2'''}}</ref><ref name="TR04">Tykoski, Ronald S.; and Rowe, Timothy. (2004). "Ceratosauria", in ''The Dinosauria'' (2nd). 47–70.</ref> |

In 2000, American palaeontologists James Madsen and Samuel Welles referred the ''L.''? ''stechowi'' teeth to ''[[Ceratosaurus]]'' sp''.'' (of uncertain species), because they resembled teeth from the [[Glossary of dinosaur anatomy#premaxilla|premaxilla]] and [[Glossary of dinosaur anatomy#dentary|dentary]] jaw bones of ''Ceratosaurus'', a theropod from the North American [[Morrison Formation]].<ref name="MW00" /> In 2007, American palaeontologist Denver Fowler instead proposed that the teeth were those of a [[Spinosauridae|spinosaurid]] dinosaur similar to ''[[Baryonyx]]'', which would make it among the oldest known spinosaurid fossils and thus some of the earliest evidence of the group.<ref name="Fowler2007">{{cite journal|last1=Fowler|first1=D. W.|date=2007|title=Recently rediscovered baryonychine teeth (Dinosauria: Theropoda): New morphologic data, range extension & similarity to ''Ceratosaurus''|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271217531|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=27|issue=3|pages=3}}</ref> This analysis was maintained by French palaeontologist [[Eric Buffetaut]], who examined the teeth that year, and in a 2008 paper referred specimen MB R 1084 to the Spinosauridae. Bufetaut found that this specimen differed from other teeth previously referred to ''L.''? ''stechowi'', and that another isolated tooth (MB R 1091) from the Middle Dinosaur Member might represent the same animal.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Buffetaut|first=Eric|date=2008|title=Spinosaurid teeth from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania, with remarks on the evolutionary and biogeographical history of the Spinosauridae|url=https://www.academia.edu/3101178|journal=Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon|language=en|volume=164|pages=26–28|via=}}</ref> He also questioned Janensch's provisional assignment of the teeth to the dubious [[genus]] ''Labrosaurus'', which was based on scant remains from the Morrison Formation that were later attributed to ''[[Allosaurus]].''<ref name=":0" />''<ref name="HMC042">{{cite book|last=Holtz|first=Thomas R., Jr.|title=The Dinosauria|author2=Molnar, Ralph E.|author3=Currie, Philip J.|publisher=University of California Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-520-24209-8|editor=Weishampel David B.|edition=2nd|location=Berkeley|pages=71–110|chapter=Basal Tetanurae|authorlink=Thomas R. Holtz, Jr.|editor2=Dodson, Peter|editor3=Osmólska, Halszka}}</ref>'' Furthermore, Buffetaut noted that the ''L''. ''sulcatus'' tooth illustrated by Marsh is now regarded as belonging to ''Ceratosaurus''.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> Similarly, ''L''. ''stechowi'' has been relegated as a [[Dubious name|dubious]] [[Ceratosauria|ceratosaurian]] related to ''Ceratosaurus''.<ref name="MW00">{{cite book|last=Madsen|first=James H.|title=Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda), a Revised Osteology|author2=Welles, Samuel P.|publisher=Utah Geological Survey|year=2000|series=Miscellaneous Publication, '''00-2'''}}</ref><ref name="TR04">Tykoski, Ronald S.; and Rowe, Timothy. (2004). "Ceratosauria", in ''The Dinosauria'' (2nd). 47–70.</ref> |

||

[[File:Ceratosaurus mount utah museum 1.jpg|thumb|Most of the teeth originally attributed to the same [[taxon]] as ''Ostafrikasaurus'' teeth are now believed to have represented ''[[Ceratosaurus]]'' (pictured) or a similar animal]] |

[[File:Ceratosaurus mount utah museum 1.jpg|thumb|Most of the teeth originally attributed to the same [[taxon]] as ''Ostafrikasaurus'' teeth are now believed to have represented ''[[Ceratosaurus]]'' (pictured) or a similar animal]] |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

[[File:Ostafrikasaurus_crassiserratus_by_PaleoGeek.png|thumb|Hypothetical life [[paleoart|restoration]] as a primitive [[Spinosauridae|spinosaurid]]|alt=|left]] |

[[File:Ostafrikasaurus_crassiserratus_by_PaleoGeek.png|thumb|Hypothetical life [[paleoart|restoration]] as a primitive [[Spinosauridae|spinosaurid]]|alt=|left]] |

||

In 2016, Spanish palaeontologists Molina-Pérez and Larramendi estimated ''Ostafrikasaurus'' at about {{convert|8.4|m|ft}} long, {{convert|2.1|m|ft|abbr=on}} tall at the hips and weighing {{convert|1.15|t|lb}}.<ref name=":20">{{Cite book|last=Molina-Peréz & Larramendi|title=Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos|publisher=Larousse|year=2016|isbn=9780565094973|location=Barcelona, Spain|pages=275}}</ref> However, without more complete material, such as a skull or body fossil, the body size and weight of fragmentary spinosaur taxa, especially those known only from teeth, can not be reliably calculated.<ref name="hone2017">{{Cite journal|last=Hone|first=David William Elliott|last2=Holtz|first2=Thomas Richard|date=June 2017|title=A century of spinosaurs – a review and revision of the Spinosauridae with comments on their ecology|journal=Acta Geologica Sinica – English Edition|language=en|volume=91|issue=3|pages=1120–1132|doi=10.1111/1755-6724.13328|issn=1000-9515}}</ref> |

In 2016, Spanish palaeontologists Molina-Pérez and Larramendi estimated ''Ostafrikasaurus'' at about {{convert|8.4|m|ft}} long, {{convert|2.1|m|ft|abbr=on}} tall at the hips and weighing {{convert|1.15|t|lb}}.<ref name=":20">{{Cite book|last=Molina-Peréz & Larramendi|title=Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos|publisher=Larousse|year=2016|isbn=9780565094973|location=Barcelona, Spain|pages=275}}</ref> However, without more complete material, such as a skull or body fossil, the body size and weight of fragmentary spinosaur taxa, especially those known only from teeth, can not be reliably calculated. Thus estimates are only tentative.<ref name="hone2017">{{Cite journal|last=Hone|first=David William Elliott|last2=Holtz|first2=Thomas Richard|date=June 2017|title=A century of spinosaurs – a review and revision of the Spinosauridae with comments on their ecology|journal=Acta Geologica Sinica – English Edition|language=en|volume=91|issue=3|pages=1120–1132|doi=10.1111/1755-6724.13328|issn=1000-9515}}</ref> |

||

The holotype tooth is thick, somewhat flattened sideways, and {{Convert|46|mm|}} in length from top to bottom. Its tip has been rounded by [[erosion]] and the base is not fully preserved. The tooth crown has well-defined carinae (cutting edges), with the front carina being curved and the back carina almost straight. There is only mild side-to-side curvature. Both carinae are serrated, with rounded denticles perpendicular to the edge of the tooth. The serrations have no inderdenticle sulci, or grooves, in between them. They line the front carina from the base to its tip, and probably also did on the back carina, whose base has been largely eroded. Towards the tip of the tooth, these serrations are very worn down (especially on the front carina). On the front carina, there are two [[Denticle (tooth feature)|denticles]] per mm (0.04 in) near the tip of the tooth, and three to four per mm (0.04 in) as the denticles shrink towards the base of the crown. There are two denticles per mm (0.04 in) all along the back carina. The serrations are notably larger than in all other known spinosaurids.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> |

The holotype tooth is thick, somewhat flattened sideways, and {{Convert|46|mm|}} in length from top to bottom. Its tip has been rounded by [[erosion]] and the base is not fully preserved. The tooth crown has well-defined carinae (cutting edges), with the front carina being curved and the back carina almost straight. There is only mild side-to-side curvature. Both carinae are serrated, with rounded denticles perpendicular to the edge of the tooth. The serrations have no inderdenticle sulci, or grooves, in between them. They line the front carina from the base to its tip, and probably also did on the back carina, whose base has been largely eroded. Towards the tip of the tooth, these serrations are very worn down (especially on the front carina). On the front carina, there are two [[Denticle (tooth feature)|denticles]] per mm (0.04 in) near the tip of the tooth, and three to four per mm (0.04 in) as the denticles shrink towards the base of the crown. There are two denticles per mm (0.04 in) all along the back carina. The serrations are notably larger than in all other known spinosaurids.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

The Upper Dinosaur Member of the Tendaguru Formation is composed mostly of [[Siltstone|siltstones]], [[calcareous]] [[Sandstone|sandstones]], and [[claystone]] [[Bed (geology)|bed]]s. These rocks likely date back to the Tithonian stage of the Late Jurassic Period, approximately 152.1 to 145 million years ago.<ref name=":22" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.stratigraphy.org/index.php/ics-chart-timescale|title=ICS - Chart/Time Scale|website=www.stratigraphy.org|language=en-gb|access-date=2018-07-13}}</ref> However, the precise chronological boundary between the [[Early Cretaceous]] and Late Jurassic of the Tendaguru Formation is still unclear.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> ''Ostafrikasaurus''' habitat would have been [[Subtropics|subtropical]] to [[Tropics|tropical]], shifting between periodic rainfall and pronounced dry seasons. Three types of palaeoenvironments were present at the Tendaguru Formation, the first was a shallow water marine setting with [[lagoon]]-like conditions shielded behind [[shoal]]s of [[ooid]] and [[siliciclastic]] rocks, evidently subjected to tides and storms. The second was a coastal environment of [[tidal flats]], consisting of [[brackish water]] lakes, ponds, and [[Fluvial|fluvial channels]]. There was little plant-life at this ecosystem for [[Sauropoda|sauropod]]s to feed on and most dinosaurs likely came to the area only during droughts. The third and most inland habitat would have been dominated by [[conifer]] plants in a well-vegetated area, offering a large feeding ground for sauropod dinosaurs.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Aberhan|first=Martin|last2=Bussert|first2=R|last3=Heinrich|first3=Wolf-Dieter|last4=Schrank|first4=E|last5=Schultka|first5=Stephan|last6=Sames|first6=Benjamin|last7=Kriwet|first7=Jürgen|last8=Kapilima|first8=S|date=2002-01-01|title=Palaeoecology and depositional environments of the Tendaguru Beds (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Tanzania)|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307803627|journal=Fossil Record|volume=5|pages=19–44|doi=10.5194/fr-5-19-2002}}</ref> |

The Upper Dinosaur Member of the Tendaguru Formation is composed mostly of [[Siltstone|siltstones]], [[calcareous]] [[Sandstone|sandstones]], and [[claystone]] [[Bed (geology)|bed]]s. These rocks likely date back to the Tithonian stage of the Late Jurassic Period, approximately 152.1 to 145 million years ago.<ref name=":22" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.stratigraphy.org/index.php/ics-chart-timescale|title=ICS - Chart/Time Scale|website=www.stratigraphy.org|language=en-gb|access-date=2018-07-13}}</ref> However, the precise chronological boundary between the [[Early Cretaceous]] and Late Jurassic of the Tendaguru Formation is still unclear.<ref name="Ostafrikasaurus2" /> ''Ostafrikasaurus''' habitat would have been [[Subtropics|subtropical]] to [[Tropics|tropical]], shifting between periodic rainfall and pronounced dry seasons. Three types of palaeoenvironments were present at the Tendaguru Formation, the first was a shallow water marine setting with [[lagoon]]-like conditions shielded behind [[shoal]]s of [[ooid]] and [[siliciclastic]] rocks, evidently subjected to tides and storms. The second was a coastal environment of [[tidal flats]], consisting of [[brackish water]] lakes, ponds, and [[Fluvial|fluvial channels]]. There was little plant-life at this ecosystem for [[Sauropoda|sauropod]]s to feed on and most dinosaurs likely came to the area only during droughts. The third and most inland habitat would have been dominated by [[conifer]] plants in a well-vegetated area, offering a large feeding ground for sauropod dinosaurs.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Aberhan|first=Martin|last2=Bussert|first2=R|last3=Heinrich|first3=Wolf-Dieter|last4=Schrank|first4=E|last5=Schultka|first5=Stephan|last6=Sames|first6=Benjamin|last7=Kriwet|first7=Jürgen|last8=Kapilima|first8=S|date=2002-01-01|title=Palaeoecology and depositional environments of the Tendaguru Beds (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Tanzania)|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307803627|journal=Fossil Record|volume=5|pages=19–44|doi=10.5194/fr-5-19-2002}}</ref> |

||

The Tendaguru Formation was home to a diverse abundance of organisms. [[Invertebrate|Invertebrates]] like [[Bivalvia|bivalves]], [[Gastropoda|gastropods]], [[Oyster|oysters]], [[Echinoderm|echinoderms]], [[Arthropod|arthropods]], [[Brachiopod|brachiopods]], [[Coral|corals]], and many [[microfauna]] are known from the deposits. Sauropod dinosaurs were prominent in the region, represented by ''[[Giraffatitan]] brancai'', ''[[Dicraeosaurus]] hansemanni'' and ''D. sattleri'', ''[[Australodocus]] bohetii'', ''[[Janenschia]] robusta'', ''[[Tornieria]]'' ''africana'' |

The Tendaguru Formation was home to a diverse abundance of organisms. [[Invertebrate|Invertebrates]] like [[Bivalvia|bivalves]], [[Gastropoda|gastropods]], [[Oyster|oysters]], [[Echinoderm|echinoderms]], [[Arthropod|arthropods]], [[Brachiopod|brachiopods]], [[Coral|corals]], and many [[microfauna]] are known from the deposits. Sauropod dinosaurs were prominent in the region, represented by ''[[Giraffatitan]] brancai'', ''[[Dicraeosaurus]] hansemanni'' and ''D. sattleri'', ''[[Australodocus]] bohetii'', ''[[Janenschia]] robusta'', ''[[Tornieria]]'' ''africana'', ''[[Tendaguria]] tanzaniensis'', and ''[[Wamweracaudia]] keranjei''. They would have coexisted with low-browsing [[Ornithischia|ornithischians]] like the [[ornithopod]] ''[[Dysalotosaurus]] lettowvorbecki'', and the [[Stegosauria|stegosaurian]] ''[[Kentrosaurus]] aethiopicus.''<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Bussert|first=Robert|last2=Heinrich|first2=Wolf-Dieter|last3=Aberhan|first3=Martin|date=2009-08-01|title=The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230014275|journal=Fossil Record|volume=12|issue=2|pages=141–174|doi=10.1002/mmng.200900004}}</ref><ref name="EoDP">{{cite book|title=The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals|publisher=Marshall Editions|year=1999|isbn=978-1-84028-152-1|editor=Palmer, D.|location=London|page=132}}</ref><ref name="Mannion2019">Philip D Mannion, Paul Upchurch, Daniela Schwarz, Oliver Wings, 2019, "Taxonomic affinities of the putative titanosaurs from the Late Jurassic Tendaguru Formation of Tanzania: phylogenetic and biogeographic implications for eusauropod dinosaur evolution", ''Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society'', zly068, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zly068</ref> Theropods besides ''Ostafrikasaurus'' included the [[Carcharodontosauridae|carcharodontosaurid]] ''[[Veterupristisaurus]]'' ''milneri'' and the [[Noasauridae|noasaurid]] ''[[Elaphrosaurus]] bambergi''. Fragmentary material also indicates the presence of a basal ceratosaurid (''Ceratosaurus''? ''stechowi'') and [[Tetanurae|tetanuran]], an unidentified [[abelisaur|abelisauroid]], as well as a possible [[Abelisauridae|abelisaurid]], carcharodontosaurid, and [[Megalosauroidea|megalosauroid]].<ref name="Veterupristisaurus" /> Non-dinosaurian vertebrates were represented by [[pterosaur|pterosaurs]] such as ''[[Tendaguripterus]]'' ''recki'', and an indeterminate [[Dsungaripteroidea|dsungaripteroid]], [[Azhdarchidae|azhdarchid]], and possible [[Archaeopterodactyloidea|archaeopterodactyloid]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Costa|first=Fabiana R.|last2=Kellner|first2=Alexander W. A.|date=2009|title=On two pterosaur humeri from the Tendaguru beds (Upper Jurassic, Tanzania)|url=http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0001-37652009000400017&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en|journal=Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências|language=en|volume=81|issue=4|pages=813–818|doi=10.1590/S0001-37652009000400017|issn=0001-3765|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barrett|first=P.M.|last2=Butler|first2=R.J.|last3=Edwards|first3=N.P.|last4=Milner.|first4=A.R.|date=2008|title=Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas, pp.61-107, in Flugsaurier: Pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer - Hone, D.W.E., and Buffetaut, É. (eds)|url=https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/12007/1/zitteliana_2008_b28_05.pdf|journal=Zitteliana|volume=28|pages=1–264|via=epub}}</ref> and the [[Crocodyliformes|crocodyliform]] ''[[Bernissartia]]'' sp.. as well as the [[ray finned fish]] ''[[Lepidotes]]'' sp. and unidentified [[selachians]] and [[Teleost|teleosts]]. There were also [[Amphibian|amphibians]], [[Paramacellodidae|paramacellodid]] lizards, and various small [[Mammal|mammals]],<ref name=":2" /> including ''[[Brancatherulum]]'' ''tendagurense'',<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Averianov|first=A. O.|last2=Martin|first2=T.|date=2015|title=Ontogeny and taxonomy of ''Paurodon valens'' (Mammalia, Cladotheria) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of USA|url=https://spbu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/ontogeny-and-taxonomy-of-paurodon-valens-mammalia-cladotheria-fro|journal=Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS|volume=319|pages=326–340|via=}}</ref> ''[[Allostaffia]] aenigmatica,'' ''[[Tendagurodon]] janenschi'', ''[[Tendagurutherium]] dietrichi'', and multiple unidentified [[Symmetrodonta|symmetrodonts]].<ref name=":2" /> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 19:19, 20 April 2020

| Ostafrikasaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, (Tithonian)

| |

|---|---|

| |

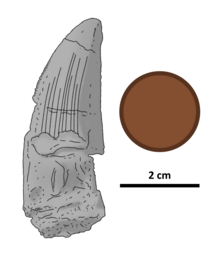

| Illustrated holotype tooth, with British penny for scale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Carnosauria (?) |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae (?) |

| Genus: | †Ostafrikasaurus Buffetaut, 2012 |

| Species: | †O. crassiserratus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus Buffetaut, 2012

| |

Ostafrikasaurus is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Period of what is now Tanzania. It is known only from fossil teeth, which were discovered during expeditions to the Tendaguru Formation by the Natural History Museum of Berlin, from 1909 to 1912. Eight teeth collected during the expedition were originally attributed to the dubious dinosaur genus Labrosaurus, and later to Ceratosaurus, both known from the American Morrison Formation. Subsequent studies resulted in them being identified as those of a spinosaurid dinosaur. In 2012, French palaeontologist Eric Buffetaut used one of said teeth to name the new genus and species Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus, identifying it as an early member of the group. He also referred another tooth from the series to the same species. Its generic name comes from the German word for "German East Africa", the former name of the colony in which the fossils were found, while the specific name comes from the Latin words for "thick" and "serrated", in reference to the form of the animal's teeth.

Ostafrikasaurus has been estimated at possibly 8.4 metres (28 ft) long and 1.15 tonnes (2,500 lb) in weight. The holotype tooth is 46 millimetres (1.8 in) long, has a curved front edge, and is oval-shaped in cross section. The tooth shows serrations that—for spinosaur standards—are unusually large, more so than in any other known taxon. Both the front and back cutting edges are serrated, with two to four denticles per millimetre (0.04 in). The tooth also has longitudinal ridges on both sides, and the outermost enamel layer has a wrinkled texture in the regions between and without ridges.

Some palaeontologists have questioned the validity of Ostafrikasaurus, given the difficulties with identifying isolated teeth from theropod dinosaurs. Ostafrikasaurus's well-developed serrations, compared to the smaller, finer ones of later relatives like Baryonyx, and the lack of serrations of even more derived spinosaurids like Spinosaurus, indicates that spinosaurids lost their serrations throughout their evolution. This is possibly because they were becoming more specialized for a piscivorous (or fish-eating) diet, which is typically associated with straighter, cone-shaped dentition with little to no serrations. Ostafrikasaurus lived in a subtropical to tropical environment alongside many other dinosaurs, as well as pterosaurs, crocodyliforms, fish, small mammals, and numerous invertebrates.

History of research

During the time of the German colonial empire, the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) of Berlin arranged an expedition in German East Africa (now Tanzania) that took place from 1909 to 1912, and is now regarded by scientists as one of the largest expeditions in palaeontological history. Most of the excavations were situated in the southeastern Tendaguru Formation, a fossil-rich site part of the Mandawa Basin dated to the Late Jurassic Period.[1][2] Among the many dinosaur fossils retrieved from the dig sites were 230 specimens of theropod teeth.[3] One of these was an isolated tooth catalogued as MB R 1084, found either nearby or atop Tendaguru Hill at the Upper Dinosaur Member.[4] It was originally attributed to the species Labrosaurus? stechowi in 1920 by German palaeontologist Werner Janensch, based on comparable ornamentation to a tooth described as Labrosaurus sulcatus by Othniel Charles Marsh.[3] A detailed monograph by Janensch published in 1925 assigned MB R 1084, as well as eight teeth from the Middle Dinosaur Member to L.? stechowi and divided them into five morphotypes (from a to e).[5]

In 2000, American palaeontologists James Madsen and Samuel Welles referred the L.? stechowi teeth to Ceratosaurus sp. (of uncertain species), because they resembled teeth from the premaxilla and dentary jaw bones of Ceratosaurus, a theropod from the North American Morrison Formation.[6] In 2007, American palaeontologist Denver Fowler instead proposed that the teeth were those of a spinosaurid dinosaur similar to Baryonyx, which would make it among the oldest known spinosaurid fossils and thus some of the earliest evidence of the group.[7] This analysis was maintained by French palaeontologist Eric Buffetaut, who examined the teeth that year, and in a 2008 paper referred specimen MB R 1084 to the Spinosauridae. Bufetaut found that this specimen differed from other teeth previously referred to L.? stechowi, and that another isolated tooth (MB R 1091) from the Middle Dinosaur Member might represent the same animal.[8] He also questioned Janensch's provisional assignment of the teeth to the dubious genus Labrosaurus, which was based on scant remains from the Morrison Formation that were later attributed to Allosaurus.[8][9] Furthermore, Buffetaut noted that the L. sulcatus tooth illustrated by Marsh is now regarded as belonging to Ceratosaurus.[4] Similarly, L. stechowi has been relegated as a dubious ceratosaurian related to Ceratosaurus.[6][10]

In 2011, German palaeontologist Oliver Rauhut considered the Middle Dinosaur Member teeth ascribed to L.? stechowi as lacking diagnostic characters (unique derived traits), concurring that the species is a dubious name. Rauhut noted that they can still be differentiated from other theropod teeth from the Tendaguru Formation, based on their slight recurvature and sideways flattening of the tooth crown, and broad ridges on the lingual flank (which faced the inside of the mouth).[11] He recognized L. sulcatus as a dubious name, since the tooth referred to it was shown only in a single illustration and not properly described in text. In addition, the original remains of Labrosaurus did not include teeth, and an additional species, Labrosaurus ferox (now considered synonymous with Allosaurus fragillis[12]), was based on a dentary bone bearing teeth of different morphology to those of L. sulcatus. Thus, Rauhut concluded there was no basis for attributing the Tendaguru teeth to Labrosaurus. He tentatively referred all of them except MB R 1084 to Ceratosaurus (under the name Ceratosaurus? stechowi), on the basis of anatomical similarities with teeth from that genus. According to Rauhut, the different features between Janensch's type b, c, e, and d teeth did not represent distinct taxa, but rather variation along the tooth row in the animal's jaws. Rauhut also attributed another tooth (MB R 1093) described by Janensch, yet not referred to L.? stechowi, to the same taxon.[11]

Rauhut also found that Janensch's type a (MB R 1084) was distinct in form from the other eight teeth, and possibly represented a different taxon closely related to C.? stechowi. He listed some differences between it and the other teeth originally referred to L.? stechowi: MB R 1084 has more lingual ridges (up to eleven) and three ridges and grooves on the labial side, which faced the outside of the mouth. Moreover, some of MB R 1084's ridges are confined to the base of the crown, joined by longer ridges extending throughout almost the whole length of the crown, with a 5 mm (0.20 in) high region at the tip of the tooth lacking any ornamentation. Additionally, ridges are present over almost the entire front three-fifths of the crown, whereas the rear two-fifths are smooth. Towards the front of the tooth, the ridged part is separated from the carina (cutting edge) by an area that is slightly concave front to back. The only similarities between MB R 1084 and the Middle Dinosaur Member teeth lie in their general shape and density of their serrations, as all teeth have 10 denticles per 5 millimetres (0.20 in) on the rear carina and 13 denticles per 5 millimetres (0.20 in) on the front carina.[11]

In a 2012 paper, Buffetaut used MB R 1084 as the holotype specimen for the new genus and species Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus, describing it as an early spinosaurid theropod. Its generic name is derived from the German name of the colony in which the fossils were found, Deutsch-Ostafrika, meaning "German East Africa", combined with the Greek σαῦρος (sauros), meaning "lizard" or "reptile". The specific name comes from the Latin crassus, meaning "thick"; and serratus, meaning "serrated", in reference to the large serrations of its teeth. Due to similarities with MB R 1084, Buffetaut assigned MB R 1091 from the Middle Dinosaur Member to the same species. Both teeth have a curved front carina, no side to side curvature, and a comparable shape in cross section. Their main differences include MB R 1091 having five lengthwise ridges on its lingual side compared to MB R 1084's ten, the ridges on the former being less extensive. MB R 1091 also had less wrinkled tooth enamel. Buffetaut notes that these differences could be explained by individual variation within the taxon, but since both teeth originated from different members of the Tendaguru Formation, the referral is only tentative.[4]

Buffetaut elaborated on the differences between the teeth of Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus and Janensch's L.? stechowi morphotypes. Morphotype b (MB R 1083 and 1087) teeth had both front to back and side to side curvature, and a D-shaped cross section. Morphotype c (MB R 1090) was curved side to side but not front to back, was not flattened from side to side, had a rounded front with no carina, and bore five strong ridges on its lingual side, but none on its labial flank. Morphotype e (MB R 1092) resembled a typical theropod tooth. It is strongly flattened from side to side, curved from front to back, shows 3 denticles per millimetre (0.04 in), its front carina does not extend to the base of the crown, and there is no ornamentation aside from some weak furrowing of the crown, and two incipient ridges on the lingual side.[4]

Description

In 2016, Spanish palaeontologists Molina-Pérez and Larramendi estimated Ostafrikasaurus at about 8.4 metres (28 ft) long, 2.1 m (6.9 ft) tall at the hips and weighing 1.15 tonnes (2,500 lb).[13] However, without more complete material, such as a skull or body fossil, the body size and weight of fragmentary spinosaur taxa, especially those known only from teeth, can not be reliably calculated. Thus estimates are only tentative.[14]

The holotype tooth is thick, somewhat flattened sideways, and 46 millimetres (1.8 in) in length from top to bottom. Its tip has been rounded by erosion and the base is not fully preserved. The tooth crown has well-defined carinae (cutting edges), with the front carina being curved and the back carina almost straight. There is only mild side-to-side curvature. Both carinae are serrated, with rounded denticles perpendicular to the edge of the tooth. The serrations have no inderdenticle sulci, or grooves, in between them. They line the front carina from the base to its tip, and probably also did on the back carina, whose base has been largely eroded. Towards the tip of the tooth, these serrations are very worn down (especially on the front carina). On the front carina, there are two denticles per mm (0.04 in) near the tip of the tooth, and three to four per mm (0.04 in) as the denticles shrink towards the base of the crown. There are two denticles per mm (0.04 in) all along the back carina. The serrations are notably larger than in all other known spinosaurids.[4]

The enamel (outermost layer) of the tooth bears a series of ridges on its surface - 10 on the lingual side, and four fainter, less extensive ones on the labial side. The gaps between ridges are 1 mm (0.039 in) wide at most. None of the ridges on either side reach the tip of the crown. There is a 3 mm (0.12 in) wide region at the front of the tooth on both sides that lacks ridges; a similar area on the rear of the tooth side diminishes in width, from 8 to 4 mm (0.31 to 0.16 in) as it approaches the tip of the crown. On both sides of the tooth, between the ridges and ridge-less parts of the teeth, the enamel surface is finely wrinkled.[4]

Classification

Spinosaurids are usually separated into two subfamilies: Baryonychinae and Spinosaurinae. In regards to dental traits, baryonychines are characterized by slightly curved, finely-serrated teeth with more oval cross sections, while spinosaurine teeth are straight, bear highly reduced or completely absent serrations, have more circular cross sections, and bear prominent flutes (lengthwise grooves) on their enamel.[14][15] In 2007, Fowler interpreted the L.? stechowi teeth as representing a possible primitive baryonychine or ancestral form to baryonychines, since they share features, such as tightly-packed serrations, stout shape, marginally flattened tooth crowns, and ridges on their lingual face, typically associated with that clade.[7] In 2008, Buffetaut separated only Janensch's morphotype a (MB R 1084) and d (MB R 1091) as having baryonychine characteristics, which in the former included its general form, somewhat flattened cross section, finely wrinkled enamel, ridges that do not reach the tip of the tooth, and having more ridges on the lingual than labial side. In MB R 1091, only one side of the tooth has ridges, which can also be observed in the teeth of Baryonyx's holotype specimen. Furthermore, Buffetaut added that the only resemblance the other types (b, c, and e) share with Janensch's type a and d is ridges covering part of the tooth c rown, while in all other aspects, such as their shape and cross section, they are substantially different. In Buffetaut's analysis, types b, c, and e are probably ceratosaurid in origin, while type a likely represents an early spinosaurid that is different from Early Cretaceous baryonychines.[8]

Rauhut was doubtful of this interpretation in 2011, stating that MB R 1084 has more similarities than differences with Ceratosaurus? stechowi teeth, like the rounded cross section, only marginal curvature of the crown, a more convex lingual than labial side, and similar size and shape of the denticles. Thus, according to his analysis, only the ridge count and distribution were left as unique to MB R 1084. Rauhut noted that though baryonychines also have ridges on either side of their teeth, they are usually most developed at the rear of the tooth, whereas MB R 1084 lacks ridges on that side. He also asserts that the wrinkling Buffetaut observed in MB R 1084's enamel is very faint and largely restricted to the lingual side, compared to the more conspicuously grainy texture of Baryonyx teeth. According to Rauhut, though MB R 1084 is potentially spinosaurid in origin, it shares only generic resemblance to baryonychine teeth, and instead probably represents a close relative of Ceratosaurus? stechowi.[11] In Buffetaut's 2012 naming of Ostafrikasaurus, he placed it in the Spinosauridae, asserting instead that the tooth is very much akin to those of baryonychines including Baryonyx. Among their shared dental features he included the slight sideways-flattening of the crown, fine enamel wrinkles, and ridges on both sides that do not reach the tooth tip, and are stronger and more numerous on the lingual than labial face. If this identification is correct, Ostafrikasaurus represents some of the earliest known evidence of spinosaurids.[16] The naming and distinction of new dinosaurs based solely on teeth has been time and again considered problematic by palaeontologists, such as with the debated identity of the spinosaurid genus Siamosaurus.[14][17] However, Buffetaut stated that with thorough comparison and analysis of morphological features such as ornamentation, theropod teeth can be sufficiently diagnostic enough to raise new taxa. He elaborated that spinosaurid teeth in particular share a unique morphology very divergent to those of other theropods.[16]

Evolution

Fowler noted in 2007 that a baryonychine identification for the L.? stechowi teeth would suit biogeographical models proposed at the time for spinosaur evolution and distribution, which assumed an origin for the group in the southern supercontinent Gondwana, with later spread and diversification in Europe. He also put forward the possibility of spinosaurids having evolved from ceratosaurian ancestors, given that baryonychine teeth have ridges on their crowns reminiscent to those seen on the premaxillary and dentary teeth of Ceratosaurus.[7] In 2008, Buffetaut rejected this proposal, because the D-shaped cross section of said Ceratosaurus teeth is not present in those of baryonychines.[8]

The main difference between MB R 1084 and all other known spinosaurid teeth, as Buffetaut noted, was in the large size of the denticles borne by the carinae. This led him to hypothesize in 2008 that spinosaurid dental evolution was largely characterized by the shrinking and eventual loss of serrations.[8] In 2012, Buffetaut posited that this pattern would begin with large serrations in primitive Jurassic taxa like Ostafrikasaurus (from the Tithonian age), which resembled those of typical, similarly-sized theropods. These would then evolve into the fine, reduced, and more numerous serrations of Early Cretaceous baryonychines, like Baryonyx from the Barremian of Europe, and Suchomimus from the Aptian to Albian of West Africa. Baryonyx, for example, had seven denticles per mm (0.04 in) in comparison to Ostafrikasaurus's two to four. Finally, the denticles would disappear entirely in spinosaurines such as Spinosaurus from the Albian to Turonian of North Africa.[15][16] Buffetaut points out that the heavily diminished serrations in taxa like Siamosaurus, from the Barremian of Thailand, seem to represent an intermediate form. He also noted similarities between Ostafrikasaurus's dentition and a set of Baryonyx-like teeth from the pre-Aptian Cabao Formation of Libya, with potentially important biogeographical implications. These teeth are similar in their general shape, oval-cross section, and wrinkled crown surface, but differ in having smaller serrations, and flutes instead of ridges.[16]

In 2012, Buffetaut added that due to the presence of such a basal spinosaurid as Ostafrikasaurus in Africa, spinosaurids may have been widespread early in their evolutionary history. He deemed this especially likely due to the discovery of spinosaurid fossils in Asia, which was likely separated from other continents during much of the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous as Pangaea continued breaking up. Though Buffetaut notes that a dispersal event in Early Cretaceous Asia could also be responsible for the presence of spinosaurids there.[4] An early global distribution for the group was also deemed likely by authors such as Stephen Brusatte and colleagues in 2010,[18] and Ronan Allain and colleagues in 2012, the latter having suggested that such a spread may have occurred earlier across Pangaea, prior to its breakup starting in the Late Jurassic.[19] In 2019, Spanish palaeontologist Elisabete Malafaia and colleagues also indicated a complex biogeographical pattern for spinosaurs during the Early Cretaceous.[20]

Palaeobiology

Though no skull material has been discovered for Ostrafrikasaurus, it is known that spinosaurid skulls resembled those of crocodiles; they were long, low, narrow and expanded at their front ends into a terminal rosette-like shape, with a robust secondary palate on the roof of the mouth that made them more resistant to stress and bending. In contrast, the primitive and typical condition for theropods was a tall, broader and wedge-like snout with a less developed secondary palate. The skull adaptations of spinosaurids converged with those of crocodilians; early members of the latter group had skulls similar to typical non-avian (or non-bird) theropods, later developing elongated snouts, conical teeth, and secondary palates. These adaptations may have been the result of a dietary change from terrestrial prey to fish.[21][22] In 2012, Buffetaut suggested that the reduction of serrations on spinosaurid teeth illustrated by Ostafrikasaurus may represent a transition during this shift in diet.[16] Most theropod dinosaurs have recurved, blade-like teeth with serrated carinae for slicing through flesh, whereas spinosaurid teeth evolved to be straighter, more conical, and have small or nonexistent serrations. Such dentition is seen in living piscivorous predators such as gharials, as it is better suited for piercing and maintaining grip on slippery aquatic prey so it can be swallowed whole, rather than torn apart.[14][21][23]

Palaeoecology

The Upper Dinosaur Member of the Tendaguru Formation is composed mostly of siltstones, calcareous sandstones, and claystone beds. These rocks likely date back to the Tithonian stage of the Late Jurassic Period, approximately 152.1 to 145 million years ago.[2][24] However, the precise chronological boundary between the Early Cretaceous and Late Jurassic of the Tendaguru Formation is still unclear.[4] Ostafrikasaurus' habitat would have been subtropical to tropical, shifting between periodic rainfall and pronounced dry seasons. Three types of palaeoenvironments were present at the Tendaguru Formation, the first was a shallow water marine setting with lagoon-like conditions shielded behind shoals of ooid and siliciclastic rocks, evidently subjected to tides and storms. The second was a coastal environment of tidal flats, consisting of brackish water lakes, ponds, and fluvial channels. There was little plant-life at this ecosystem for sauropods to feed on and most dinosaurs likely came to the area only during droughts. The third and most inland habitat would have been dominated by conifer plants in a well-vegetated area, offering a large feeding ground for sauropod dinosaurs.[25]

The Tendaguru Formation was home to a diverse abundance of organisms. Invertebrates like bivalves, gastropods, oysters, echinoderms, arthropods, brachiopods, corals, and many microfauna are known from the deposits. Sauropod dinosaurs were prominent in the region, represented by Giraffatitan brancai, Dicraeosaurus hansemanni and D. sattleri, Australodocus bohetii, Janenschia robusta, Tornieria africana, Tendaguria tanzaniensis, and Wamweracaudia keranjei. They would have coexisted with low-browsing ornithischians like the ornithopod Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki, and the stegosaurian Kentrosaurus aethiopicus.[26][27][28] Theropods besides Ostafrikasaurus included the carcharodontosaurid Veterupristisaurus milneri and the noasaurid Elaphrosaurus bambergi. Fragmentary material also indicates the presence of a basal ceratosaurid (Ceratosaurus? stechowi) and tetanuran, an unidentified abelisauroid, as well as a possible abelisaurid, carcharodontosaurid, and megalosauroid.[11] Non-dinosaurian vertebrates were represented by pterosaurs such as Tendaguripterus recki, and an indeterminate dsungaripteroid, azhdarchid, and possible archaeopterodactyloid.[29][30] and the crocodyliform Bernissartia sp.. as well as the ray finned fish Lepidotes sp. and unidentified selachians and teleosts. There were also amphibians, paramacellodid lizards, and various small mammals,[26] including Brancatherulum tendagurense,[31] Allostaffia aenigmatica, Tendagurodon janenschi, Tendagurutherium dietrichi, and multiple unidentified symmetrodonts.[26]

References

- ^ Tamborini, Marco; Vennen, Mareike (2017-06-05). "Disruptions and changing habits: The case of the Tendaguru expedition". Museum History Journal. 10 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1080/19369816.2017.1328872. ISSN 1936-9816.

- ^ a b Bussert, Robert; Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; Aberhan, Martin (2009-08-01). "The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy". Fossil Record. 12 (2): 141–174. doi:10.1002/mmng.200900004.

- ^ a b W. Janensch, 1920, "Ueber Elaphrosaurus bambergi und die Megalosaurier aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 1920: 225-235

- ^ a b c d e f g h Buffetaut, Eric (2012). "An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition" (PDF). Oryctos. 10: 1–8.

- ^ Janensch, W., 1925, "Die Coelurosaurier und Theropoden der Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas", Palaeontographica Supplement 7: 1–99

- ^ a b Madsen, James H.; Welles, Samuel P. (2000). Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda), a Revised Osteology. Miscellaneous Publication, 00-2. Utah Geological Survey.

- ^ a b c Fowler, D. W. (2007). "Recently rediscovered baryonychine teeth (Dinosauria: Theropoda): New morphologic data, range extension & similarity to Ceratosaurus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (3): 3.

- ^ a b c d e Buffetaut, Eric (2008). "Spinosaurid teeth from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania, with remarks on the evolutionary and biogeographical history of the Spinosauridae". Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon. 164: 26–28.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). "Basal Tetanurae". In Weishampel David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tykoski, Ronald S.; and Rowe, Timothy. (2004). "Ceratosauria", in The Dinosauria (2nd). 47–70.

- ^ a b c d e Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2011). "Theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 195–239. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01084.x (inactive 2020-04-14).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2020 (link) - ^ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). "Basal Tetanurae". In Weishampel David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Molina-Peréz & Larramendi (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Barcelona, Spain: Larousse. p. 275. ISBN 9780565094973.

- ^ a b c d Hone, David William Elliott; Holtz, Thomas Richard (June 2017). "A century of spinosaurs – a review and revision of the Spinosauridae with comments on their ecology". Acta Geologica Sinica – English Edition. 91 (3): 1120–1132. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.13328. ISSN 1000-9515.

- ^ a b Buffetaut, E.; Suteethorn, V.; Tong, H.; Amiot, R. (2008). "An Early Cretaceous spinosaur theropod from southern China". Geological Magazine. 145 (5): 745–748. Bibcode:2008GeoM..145..745B. doi:10.1017/S0016756808005360.

- ^ a b c d e Buffetaut, Eric (2012). "An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition" (PDF). Oryctos. 10: 1–8.

- ^ Sales, Marcos A. F.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2017-11-06). "Spinosaur taxonomy and evolution of craniodental features: Evidence from Brazil". PLOS One. 12 (11): e0187070. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1287070S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187070. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5673194. PMID 29107966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Brusatte, Stephen; B. J. Benson, R; Xu, Xing (2010-12-10). "The evolution of large-bodied therood dinosaurs during the Mesozoic in Asia". Journal of Iberian Geology. 36 (2): 275–296. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2010.v36.n2.12.

- ^ Allain, R.; Xaisanavong, T.; Richir, P.; Khentavong, B. (2012). "The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos". Naturwissenschaften. 99 (5): 369–377. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..369A. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0911-7. PMID 22528021.

- ^ Elisabete Malafaia; José Miguel Gasulla; Fernando Escaso; Iván Narváez; José Luis Sanz; Francisco Ortega (2019). "A new spinosaurid theropod (Dinosauria: Megalosauroidea) from the late Barremian of Vallibona, Spain: Implications for spinosaurid diversity in the Early Cretaceous of the Iberian Peninsula". Cretaceous Research. in press: 104221. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104221.

- ^ a b Holtz Jr., T. R. (1998). "Spinosaurs as crocodile mimics". Science. 282 (5392): 1276–1277. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1276.

- ^ Ibrahim, N.; Sereno, P. C.; Dal Sasso, C.; Maganuco, S.; Fabri, M.; Martill, D. M.; Zouhri, S.; Myhrvold, N.; Lurino, D. A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–1616. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. Supplementary Information

- ^ Cuff, Andrew R.; Rayfield, Emily J. (2013). "Feeding Mechanics in Spinosaurid Theropods and Extant Crocodilians". PLOS One. 8 (5): e65295. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865295C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065295. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3665537. PMID 23724135.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "ICS - Chart/Time Scale". www.stratigraphy.org. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ^ Aberhan, Martin; Bussert, R; Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; Schrank, E; Schultka, Stephan; Sames, Benjamin; Kriwet, Jürgen; Kapilima, S (2002-01-01). "Palaeoecology and depositional environments of the Tendaguru Beds (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Tanzania)". Fossil Record. 5: 19–44. doi:10.5194/fr-5-19-2002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Bussert, Robert; Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; Aberhan, Martin (2009-08-01). "The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy". Fossil Record. 12 (2): 141–174. doi:10.1002/mmng.200900004.

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- ^ Philip D Mannion, Paul Upchurch, Daniela Schwarz, Oliver Wings, 2019, "Taxonomic affinities of the putative titanosaurs from the Late Jurassic Tendaguru Formation of Tanzania: phylogenetic and biogeographic implications for eusauropod dinosaur evolution", Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zly068, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zly068

- ^ Costa, Fabiana R.; Kellner, Alexander W. A. (2009). "On two pterosaur humeri from the Tendaguru beds (Upper Jurassic, Tanzania)". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 81 (4): 813–818. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652009000400017. ISSN 0001-3765.

- ^ Barrett, P.M.; Butler, R.J.; Edwards, N.P.; Milner., A.R. (2008). "Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas, pp.61-107, in Flugsaurier: Pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer - Hone, D.W.E., and Buffetaut, É. (eds)" (PDF). Zitteliana. 28: 1–264 – via epub.

- ^ Averianov, A. O.; Martin, T. (2015). "Ontogeny and taxonomy of Paurodon valens (Mammalia, Cladotheria) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of USA". Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 319: 326–340.