1880 Greenback National Convention

| 1880 presidential election | |

Nominees Weaver and Chambers | |

| Convention | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | June 9–11, 1880 |

| City | Chicago, Illinois |

| Venue | Interstate Exposition Building |

| Candidates | |

| Presidential nominee | James B. Weaver of Iowa |

| Vice-presidential nominee | Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas |

The 1880 Greenback Party National Convention convened at the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago from June 9 to 11, 1880, to select presidential and vice presidential nominees and write a party platform for the Greenback Party in the United States presidential election of 1880. Delegates chose James B. Weaver of Iowa for President and Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas for Vice President.

The Greenback Party was a newcomer to the political scene in 1880, having arisen, mostly in the nation's West and South, as a response to the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873. During the American Civil War, Congress had authorized "greenbacks," a form of money redeemable in government bonds, rather than in gold, as was traditional. After the war, many Democrats and Republicans in the East sought to return to the gold standard, and the government began to withdraw greenbacks from circulation. The reduction of the money supply, combined with the economic depression, made life harder for debtors, farmers, and industrial laborers; the Greenback Party hoped to draw support from these groups.

Six men were candidates for the presidential nomination. Weaver, an Iowa congressman and Civil War general, was the clear favorite, but two other congressmen, Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts and Hendrick B. Wright of Pennsylvania, also commanded considerable followings. Weaver triumphed quickly, winning a majority of the 850 delegates' votes on the first ballot. Chambers, a Texas businessman and Confederate veteran, was likewise nominated on the initial vote. More tumultuous was the fight over the platform, as delegates from disparate factions of the left-wing movement clashed over women's suffrage, Chinese immigration, and the extent to which the government should regulate working conditions. Votes for women was the most contentious of these, with the party ultimately endorsing the suffragists' cause, despite a vocal minority's opposition.

Weaver and Chambers left the convention with high hopes for the third party's cause, but in the end they were disappointed. The election was a close contest between the Republican, James A. Garfield, and the Democrat, Winfield Scott Hancock, with Garfield being the narrow victor. The Greenback ticket placed a distant third, netting just over three percent of the popular vote.

Background

Origins

The Greenback Party was a newcomer to politics in 1880, having first nominated candidates for national office four years earlier.[1] The party had arisen, mostly in the West and South, as a response to the economic depression that followed the Panic of 1873.[2] During the Civil War, Congress had authorized "greenbacks," a new form of fiat money that was redeemable not in gold but in government bonds.[3] The greenbacks had helped to finance the war when the government's gold supply did not keep pace with the expanding costs of maintaining the armies. When the crisis had passed, many in both the Democratic and Republican parties, especially in the East, wanted to return the nation's currency to a gold standard as soon as possible (candidates who favored the gold-backed currency were called "hard money" supporters, while the policy of encouraging inflation was known as "soft money").[4] The Specie Payment Resumption Act, passed in 1875, ordered that greenbacks be gradually withdrawn and replaced with gold-backed currency beginning in 1879.[5] At the same time, economic depression had made it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less valuable.[6] Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans offered a home to those who favored retaining the greenbacks, so many looked to create a third party that would address their concerns.[7] Greenbackers drew support from the growing labor movement in the nation's Eastern cities as well as Western and Southern farmers who had been harmed by deflation.[8] Beyond their support for a larger money supply, they also favored an eight-hour work day, safety regulations in factories, and an end to child labor.[9] As one author put it, they "anticipated by almost fifty years the progressive legislation of the first quarter of the twentieth century".[9]

In 1876, various independent delegates gathered in Indianapolis to nominate a presidential ticket to campaign on those issues.[1] For president, they chose Peter Cooper, an eighty-five-year-old industrialist and philanthropist from New York, with Samuel Fenton Cary, a former Congressman from Ohio, as his running mate.[10] The Greenback ticket fared poorly in the election that November, attracting just 81,740 votes—less than 1% of the total.[10] As bad economic times continued, however, the party gained momentum. Labor unrest the following year, culminating in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, added to many laborers' alienation from the two major parties.[11] Local movements, like California's Workingmen's Party, began to agitate for laws to improve the condition of laborers (and for an end to Chinese immigration).[12] By 1878, the third-party movement had become strong enough to elect 22 independents to the federal House of Representatives, most tied in some way to the Greenback movement.[12] As the 1880 presidential election approached, members of the Greenback Party (or Greenback-Labor Party, as it was sometimes known) had reason to believe that they could improve on the results of 1876.[13]

Party split

Attempts to fuse the disparate state and local parties into a national force led to friction between party leaders.[14] By 1879, there was a clear split, as a group led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy formed their own "Union Greenback Labor Party."[15] Pomeroy's group of mostly Southern and Western Greenbackers was opposed to electoral fusion with either of the two major parties and took more radical positions on monetary policy, including payment of all federal bonds in greenbacks, rather than the gold dollars originally promised investors.[14] They also differed from the Eastern-centered rump party (often called the "National Greenback Party") in calling for the popular election of postmasters and the death penalty as punishment for corruption in public office.[16] After a January 1880 conference in Washington, D.C. failed to unite the factions, each party called for its own national convention to nominate candidates for president.[16]

The Union Greenbackers held their convention first, meeting in St. Louis in March 1880.[15] Although much of the young party's leadership remained with the Eastern faction, the March gathering included Solon Chase and Kersey Graves, among other third party notables.[17] They nominated Stephen D. Dillaye, a New Jersey lawyer and journalist, for President and Barzillai J. Chambers, a Texas merchant and surveyor, for Vice President.[18] Because Dillaye had previously declared he was not interested in the nomination, many delegates protested, seeing Dillaye as a placeholder for eventual re-unification with the National Greenbackers.[18] Dillaye, himself, supported reunification, and Pomeroy also urged the delegates to send representatives to the Easterners' convention, which was set for June 1880 in Chicago.[19] The majority agreed with the sentiment, and Union Greenbackers gathered in Chicago along with National Greenbackers as their convention began a few months later.[19]

Candidates

Weaver

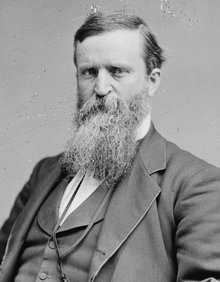

James Baird Weaver grew up on the Iowa frontier and was involved with the Republican Party from its early days in the late 1850s.[20] At the outbreak of Civil War, he joined the Union Army.[21] Weaver saw action at the battles of Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and Resaca, and rose to the rank of brevet brigadier general.[22] After the war, he continued to be active in Iowa Republican politics. Weaver sought nomination to the House of Representatives and the Governorship, but each time was defeated by candidates from the party's more conservative faction, led by William B. Allison.[23] He campaigned for the Republican presidential candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, in 1876, but also attended the 1876 Greenback National Convention as an observer.[24]

By 1877, differences with party leadership on the money question led him to consider other options.[24] After initially supporting the Republican candidate for governor that year, Weaver joined the Greenback Party in August.[25] In 1878, Weaver accepted the Greenback nomination for Iowa's 6th congressional district.[26] Although Weaver's political career up to then had been as a staunch Republican, Democrats in the 6th district considered that endorsing him was likely the only way to defeat Ezekiel S. Sampson, the incumbent Republican.[27] Despite objections from some hard-money Democrats, the Greenback-Democrat ticket prevailed, and Weaver was elected with 16,366 votes to Sampson's 14,307.[28]

Weaver entered the 46th Congress in March 1879.[29] Although the House was closely divided, neither major party included the Greenbackers in their caucus, leaving them few committee assignments and little input on legislation.[30] Weaver gave his first speech in April 1879, criticizing the use of the army to police Southern polling stations, while also decrying the violence against black Southerners that made such protection necessary; he then described the Greenback platform, which he said would put an end to the sectional and economic strife.[31] The next month, he spoke in favor of a bill calling for an increase in the money supply by allowing the unlimited coinage of silver, but the bill was easily defeated.[31] Weaver's oratorical skill drew praise, and while he was unable to advance Greenback policy ideas, he was soon considered the front-runner for the presidential nomination in 1880.[32]

Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire, and later moved to Massachusetts to pursue a legal career.[33] He built a successful practice in the 1840s and 1850s and became involved in local politics as a Democrat.[33] A compelling public speaker, Butler was first elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1853.[33] He successfully ran for a Massachusetts Senate seat in 1859.[33] Despite his Protestant upbringing, he gained a faithful following among Massachusetts Catholics and also built support among laborers.[33] In the 1860 presidential campaign, Butler sought compromise with the slave power and believed Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi should be the Democratic Party's nominee for president.[34]

Butler had been elected a brigadier general of the Massachusetts militia, and when the Civil War began in 1861, he quickly organized his men and marched south.[33] Butler's men occupied Baltimore to ensure that Maryland did not follow its fellow Southern states into secession.[35] In May of that year, he was promoted to major general and sent to command at Fort Monroe in Virginia, where he pioneered the tactic of seizing and freeing slaves as "contraband of war".[35] When Union forces captured New Orleans, Butler was sent to command there.[35] Butler's rule was harsh, and he became especially reviled among Southern whites, to whom he was known as "Beast" Butler.[34] He was transferred to the Virginia theater in 1863, where he worked under General Ulysses S. Grant's direction in the campaigns that led to the Confederacy's defeat.[35]

After the war, Butler was elected to Congress as a Republican, and soon came to identify with that party's more radical element.[35] In 1868, he was among the leaders in President Andrew Johnson's impeachment.[35] Butler's wartime exploits earned him support among blacks and abolitionists, which, combined with his existing base among laborers, ensured his reelection for several terms.[36] His radicalism made him enemies among conservative Republicans, however, and when he lost his seat in the Democratic wave of 1874, he began to shift his allegiance to the nascent Greenback Party.[37] In 1876, he returned to the House as a Republican, but in 1878 he ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts as an independent Greenbacker with Democratic support.[36] Butler had supporters across the political spectrum—he was often said to be "a member of all parties and false to each"—and was considered a presidential possibility when the Greenbackers convened in Chicago in 1880.[36]

Wright

Hendrick Bradley Wright was born and raised in northeastern Pennsylvania.[38] After studying law at Dickinson College, Wright returned to Wilkes-Barre and quickly became known as a gifted attorney and orator.[39] His powers of speech earned him notice in Pennsylvania Democratic Party circles, as well as the nickname "Old-Man-Not-Afraid-To-Be-Called-A-Demagogue".[39] He became a district attorney for Luzerne County in 1834 and was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1841.[38] Wright was reelected in 1842 and 1843, serving as Speaker in his final term.[38] He served as president of the 1844 Democratic National Convention, working with the anti-Van Buren faction to prevent that former President's nomination.[40] After the convention, he sought a seat in the United States Senate, but was unsuccessful.[38]

Wright was defeated for election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1850, but was successful in 1852.[38] Defeated for reelection in 1854, he ran in 1860 as a Democrat with Republican support, and was elected to represent Pennsylvania's 12th congressional district.[40] He spoke against the Peace Democrats early in the Civil War, but by 1864, believing the Union war aims had changed for the worse, he supported Democrat George B. McClellan for the presidency.[38] Wright did not run for reelection, returning to private life in 1863. He continued his legal career and published writings on the relationship between labor and capital.[38] His book, A Practical Treatise on Labor, was published in 1871.[38]

In 1876, Wright was elected to his old seat in Congress as a Democrat, but with support from the small Greenback movement.[41] In 1878, the situation was reversed: Wright ran as a Greenbacker, but was reelected with support by Democrats.[41] He attracted attention in Congress with his proposal to amend the Homestead Act of 1862 to establish government loans to would-be settlers of the West, making it easier for landless Easterners to claim homesteads there.[42] Congress was, on the whole, not receptive to Wright's proposal.[43] Wright proposed it again in 1879 and emphasized the conservatism of his proposal, that it was a loan secured by the homestead, not a gift from the state; even so, the bill went down to overwhelming defeat.[44] Despite his failure, Wright, like Weaver, had raised his profile as a potential presidential nominee by attempting to advance Greenback ideas in Congress.[42]

Other contenders

Several favorite son candidates had delegates interested in their nomination, although they were seen as having less of a chance of gaining the nomination.[42] Alexander Campbell had represented Illinois in the House of Representatives several years earlier. He was seen as a pragmatist who represented the Greenback Party's more conservative members. Henly James was the head of the Grange in Indiana and had served in the state legislature there, but attracted little support outside his own delegation.[42] In the Wisconsin delegation, many favored Edward P. Allis, an industrialist who owned the Reliance Iron Works.[42] Allis was a longtime supporter of soft money, but had no experience in elected office.[42] Finally, Solon Chase of Maine had some support from the New England delegations.[42] Chase was a publisher of a Greenback newspaper, Chase's Inquirer, and had narrowly lost a House election in 1878.[45] Chase was among the most radical of the Greenbackers, attracting support from the party's left-wing members.[45]

-

Businessman Edward P. Allis of Wisconsin

-

Former Representative Alexander Campbell of Illinois

-

Publisher Solon Chase of Maine

Convention

Preliminaries

The National Greenback Party delegates assembled in the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago on Wednesday, June 9, 1880.[46] The Republican convention took place in the same building and had only just ended after a record 36 rounds of balloting.[47] When the Greenbackers arrived, the Republicans' banners still hung from the walls, so the delegates were greeted by images of Abraham Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens as they entered.[48] The building, popularly known as the "Glass Palace", had been built in 1873 for an Interstate Industrial Exposition.[a][50]

Franklin P. Dewees of the party's executive committee called the convention to order at 12:30 p.m. on June 9.[46] Reverend Pearl P. Ingalls of Iowa said a brief prayer, and the convention was opened.[46] Gilbert De La Matyr, a Methodist minister and Greenback congressman from Indiana, was unanimously chosen as temporary chairman.[51] After De La Matyr gave a brief, fiery speech, they proceeded to call the roll, which included delegates from every state except Oregon.[52] As the roll call finished, Matilda Joslyn Gage, a suffragist, mounted the stage, provoking cheers from some delegates and howls of outrage from others.[53] She called for the new party to recognize women's right to vote, but the issue was avoided temporarily when the delegates voted to send her petition to a committee for further study.[54]

Reunification

The Union Greenback convention had reconvened at nearby Farwell Hall and sent an emissary to the National Greenbackers.[54] The delegates voted to join the other faction in a special conference committee to work for reunification, then adjourned until 7:30 that evening.[54] While they waited for the committees to finish their work, the delegates listened to speeches by several prominent Greenbackers, including Denis Kearney, a California labor leader, and William Wallace, a Canadian parliamentarian and advocate for currency reform.[52] Meanwhile, the Credentials Committee voted narrowly to admit the Union Greenbackers, as well as a delegation from the Socialist Labor Party.[55] The Committee on Permanent Organization voted to recommend Richard F. Trevellick, a Michigan trade union organizer, as the permanent chairman of the convention.[55] None of the reports were finished by the appointed time, so the convention adjourned again until 10:45 Thursday morning.[56]

When they reconvened, the Credentials Committee announced that there were 608 regularly selected delegates, and recommended the admission of 185 Union Greenbackers and 44 Socialist Laborites, along with a handful of others.[b][57] After a spirited and chaotic discussion, the convention voted to admit the other delegates in a voice vote: the party was reunified.[58] Messages were sent to the Union Greenbackers and Socialist Laborites informing them of the results. In the meantime, the women's suffrage supporters again tried to convince the delegates to endorse their cause.[59] Sarah Andrews Spencer mounted the stage to give an impassioned argument for women's right to vote, while Kearney climbed a nearby platform to shout his disapproval.[59] Their informal debate was interrupted by a brass band announcing the arrival of the Union Greenbackers and Socialist Laborites.[59] The convention erupted in prolonged cheering and a banner with the word "Reunion" was hoisted.[59] The convention broke for a brief recess as the delegates renewed their acquaintance with the erstwhile schismatics.[60]

Platform

The delegates voted to address the platform before deciding on nominees, and debate began when they reconvened at 8:45 p.m.[60] Many fights and compromises had been hashed out in the Resolutions Committee already, but the delegates insisted on debating several provisions.[60] On many planks, there was widespread agreement among the delegates. On the monetary issue, the platform declared that all money, whether metal or paper, should be issued by the government, not by banks (as was common for paper money at the time).[61] They also called for the unlimited coinage of silver and the repayment of the national debt in bonds, rather than gold dollars.[62] Other planks of the platform called for a graduated income tax, laws to mandate safe working conditions in factories, the regulation of interstate commerce, and an end to child and convict labor; all of these were familiar parts of Greenback platforms from earlier elections, and provoked no serious dissent.[61]

Social issues provoked greater disagreement. Kearney's Western faction gained a victory when the platform was made to include a call for an end to Chinese immigration.[61] They also turned, at last, to the issue of suffrage. They eventually agreed on a vague statement in the platform, that the party would "denounce as dangerous, the efforts everywhere manifest to restrict the right of suffrage".[63] Many of the delegates found this unsatisfying, and called for a separate resolution on the subject.[64] After more debate, a resolution calling for the enfranchisement of "every citizen" passed by a vote of 528 to 124.[64] The Socialist Labor faction proposed another resolution declaring "that land, air, and water are the grand gifts of nature to all mankind", and that no person had a right to monopolize them; the convention applauded, but the proposal was shunted off to a committee.[64]

Nominations and balloting

It was nearly midnight Thursday night when the platform fights were finished, but the delegates voted to proceed immediately to nominations for President.[65] At 1:00 Friday morning, the roll call began.[65] S.F. Norton proposed his fellow Illinoisan, Alexander Campbell, proclaiming his great financial knowledge and association with Lincoln.[65][66] James Buchanan, the editor of the Indianapolis Sun, proposed Benjamin Butler. Iowa Congressman Edward H. Gillette nominated Weaver, and Frank M. Fogg of Maine proposed "the farmer's friend", Solon Chase.[65][66] Perry Talbot of Missouri nominated the Union Greenbackers' nominee, Stephen D. Dillaye, who immediately asked that his name be withdrawn.[65] Pennsylvania's delegation nominated Hendrick Wright, and Wisconsin's closed with the nomination of Edward P. Allis.[65]

Now 3:25 a.m., the delegates took an informal ballot.[66] Weaver led the pack with about 30% of the votes, with Wright, Dillaye, and Butler trailing at about 15% each and the remaining votes scattered among the remaining candidates.[c][68] Supporters of Wright and Butler talked of combining their forces, but the momentum favored Weaver.[67] In the first formal ballot, at 4:10 a.m., Weaver gained votes, and delegates began shifting their ballots to him.[67] Without any official motion, the nomination was made unanimous, and the brass band again began to play.[67] Weaver, who was staying at the nearby Palmer House hotel, was summoned to the convention.[70] As they waited, the delegates turned to the vice presidential nomination. Some of Butler's supporters proposed nominating Absolom M. West of Mississippi, a more conservative Greenbacker, to balance the ticket against Weaver, whom they regarded as radical.[67] West, who was present at the convention, had already disappointed the radicals by opposing women's suffrage and the eight-hour day.[67] They instead proposed Barzillai J. Chambers of Texas, who had been the Union Greenbackers' nominee for vice president.[67] The majority agreed, as Chambers took 403 votes to West's 311.[71]

Weaver had still not arrived, and the Socialist Labor delegates took the opportunity to call for a re-vote on their land plank and the women's suffrage issue.[67] The delegates overruled the chairman's holding that the question was out of order and overwhelmingly voted that the "land, air, and water" plank and a plank explicitly supporting women's suffrage should be considered "part of the platform".[72] Finally, at 6:00 a.m., Weaver arrived.[61] To thunderous applause, the nominee thanked the convention for its decision and accepted the nomination.[61] At 6:45 a.m., the exhausted delegates adjourned.[72]

Aftermath

Three weeks later, Weaver published his formal letter of acceptance, calling for all party members to "go forth in the great struggle for human rights".[73] In a departure from the political traditions of the day, Weaver himself campaigned, making speeches across the South in July and August.[74] As the Greenbackers had the only ticket that included a Southerner, Weaver and Chambers hoped to make inroads in the South.[75] Chambers's own participation was limited, as before reaching home from the convention, he fell as he exited his train and broke two ribs.[76] He was confined to bed for several weeks and considered withdrawing from the race, but decided against it; his efforts were limited by his injuries, and his only contribution to the campaign was to publish his newspaper.[76]

As the campaign progressed, Weaver's message of racial inclusion drew violent protests in the South, as the Greenbackers faced the same obstacles the Republicans did in the face of increasing black disenfranchisement.[77] In the autumn, Weaver campaigned in the North, but the Greenbackers' lack of support was compounded by Weaver's refusal to run a fusion ticket in states where Democratic and Greenbacker strength might have combined to outvote the Republicans.[78]

The Greenback ticket received 305,997 votes and no electoral votes, compared to 4,446,158 for the winner, Republican James A. Garfield, and 4,444,260 for Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock.[79] The party was strongest in the West and South, but in no state did Weaver receive more than 12% of the vote, and his nationwide total was just 3%.[80] That figure represented an improvement over the Greenback vote of 1876, but to Weaver, who expected twice as many votes as he received, it was a disappointment.[81]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| James A. Garfield | Republican | Ohio | 4,446,158[82] | 48.3% | 214[82] | Chester A. Arthur | New York | 214[82] |

| Winfield S. Hancock | Democratic | Pennsylvania | 4,444,260[82] | 48.3% | 155[82] | William H. English | Indiana | 155[82] |

| James B. Weaver | Greenback Labor | Iowa | 305,997[79] | 3.3% | 0[79] | Barzillai J. Chambers | Texas | 0[79] |

| Neal Dow | Prohibition | Maine | 10,305[83] | 0.1% | 0[83] | Henry A. Thompson | Ohio | 0[83] |

| John W. Phelps | American | Vermont | 707[83] | 0.0% | 0[83] | Samuel C. Pomeroy | Kansas | 0[83] |

| Other | 3,631 | 0.0% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 9,211,051 | 100% | 369 | 369 | ||||

| Needed to win | 185 | 185 | ||||||

Notes

- ^ After the Exposition, it hosted festivals and concerts for several years until it was demolished in 1892. The Art Institute of Chicago now stands on the site.[49]

- ^ The others included six from Chicago's Eight Hour League, three from the Chicago Workingwomen's Union, three from the Workingmen's Party of Kansas, and one from Chicago's Social Political Workingmen's Society.[57]

- ^ Contemporary accounts differ on the exact tally of the informal ballot, with various sources crediting Weaver with anywhere between 220 and 235 votes.[67][68][69]

References

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Unger 1964, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Unger 1964, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Wiebe 1967, p. 6.

- ^ Unger 1964, pp. 228–233.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 28.

- ^ a b Clancy 1958, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 38.

- ^ a b Doolen 1972, pp. 442–444.

- ^ a b Barr 1967, p. 280.

- ^ a b Doolen 1972, p. 445.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 49.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 50.

- ^ a b Doolen 1972, p. 447.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, pp. 7–31.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, pp. 39–50.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, pp. 55–59.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2008, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Colbert 1978, p. 26.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 74.

- ^ Colbert 1978, p. 27.

- ^ Colbert 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 84.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2008, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b c d e f Fish 1929, p. 357.

- ^ a b Thompson 1982, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f Fish 1929, p. 358.

- ^ a b c Lause 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Fish 1929, p. 359.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boyd 1936, p. 553.

- ^ a b Clausen 1965, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Clausen 1965, pp. 203–205.

- ^ a b Boyd 1936, p. 554.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lause 2001, p. 54.

- ^ Deverell 1988, p. 274.

- ^ Deverell 1988, p. 275.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 74.

- ^ Clancy 1958, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Currey 1918, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Currey 1918, p. 151.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 63.

- ^ a b Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 75.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Lause 2001, p. 65.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Lause 2001, p. 69.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 70.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 71–74.

- ^ a b c d Lause 2001, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c Lause 2001, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e Mitchell 2008, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 81.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Lause 2001, pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b c d e f Lause 2001, pp. 79–81.

- ^ a b c Kennedy et al. 1880, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lause 2001, p. 81.

- ^ a b Indiana Democrat 1880.

- ^ La Plata Home Press 1880.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 86.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 87.

- ^ a b Lause 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 1880, p. 94.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 85–104.

- ^ a b Barr 1967, p. 282.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 105–124.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 124–146.

- ^ a b c Ackerman 2003, p. 221.

- ^ Mitchell 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Lause 2001, pp. 206–208.

- ^ a b c d NARA 2012.

- ^ a b c d Clancy 1958, p. 243.

Sources

Books

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. New York, New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1151-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boyd, Julian P. (1936). "Hendrick Bradley Wright". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. XX. New York, New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 553–554. OCLC 4171403.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clancy, Herbert J. (1958). The Presidential Election of 1880. Chicago, Illinois: Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-1-258-19190-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Currey, J. Seymour (1918). Chicago: Its History and Its Builders. Chicago, Illinois: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. OCLC 1851611.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fish, Carl Russell (1929). "Benjamin Franklin Butler". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. III. New York, New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 357–359. OCLC 4171403.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kennedy, E.B.; Dillaye, S.D.; Hill, Henry (1880). Our Presidential Candidates and Political Compendium. Newark, New Jersey: F.C. Bliss & Co. OCLC 9056547.

- Lause, Mark A. (2001). The Civil War's Last Campaign: James B. Weaver, the Greenback-Labor Party & the Politics of Race and Section. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-1917-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Robert B. (2008). Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Roseville, Minnesota: Edinborough Press. ISBN 978-1-889020-26-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Unger, Irwin (1964). The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865–1879. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04517-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wiebe, Robert H. (1967). The Search for Order: 1877–1920. New York, New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-0104-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Articles

- Barr, Alwyn (October 1967). "B. J. Chambers and the Greenback Party Split". Mid-America. 49: 276–284. OCLC 1757398.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clausen, E. Neal (April 1965). "Hendrick B. Wright and the 'Nocturnal Committee'". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 89 (2): 199–206. JSTOR 20089793.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Colbert, Thomas Burnell (Spring 1978). "Political Fusion in Iowa: The Election of James B. Weaver to Congress in 1878". Arizona and the West. 20 (1): 25–40. JSTOR 40168674.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Deverell, Wiliam F. (August 1988). "To Loosen the Safety Valve: Eastern Workers and Western Lands". The Western Historical Quarterly. 19 (3): 269–285. JSTOR 968232.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doolen, Richard M. (Winter 1972). "'Brick' Pomeroy and the Greenback Clubs". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 65 (4): 434–450. JSTOR 40191206.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Margaret S. (June 1982). "Ben Butler versus the Brahmins: Patronage and Politics in Early Gilded Age Massachusetts". The New England Quarterly. 55 (2): 163–186. JSTOR 365357.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Newspapers

- "The Greenback Convention". Indiana Democrat. Indiana, Pennsylvania. June 17, 1880.

- "The Greenback Convention". La Plata Home Press. La Plata, Missouri. June 19, 1880.

Website

- "Historical Election Results: Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.