Andromeda (mythology)

| Andromeda | |

|---|---|

| Greek mythology character | |

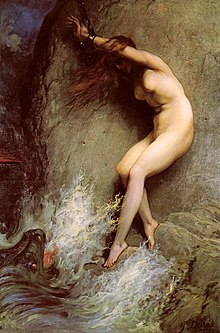

Andromède by Gustave Doré, 1869 | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Cepheus (father) Cassiopeia (mother) |

| Spouse | Perseus |

| Children | Perses, Heleus, Alcaeus, Sthenelus, Electryon, Mestor, Cynurus, Gorgophone, Autochthe |

| Origin | Aethiopia |

In Greek mythology, Andromeda (/ænˈdrɒmɪdə/; Greek: Ἀνδρομέδα, Androméda or Ἀνδρομέδη, Andromédē) is the daughter of the king of Aethiopia, Cepheus, and his wife Cassiopeia. When Cassiopeia boasts that she is more beautiful than the Nereids, Poseidon sends the sea monster Cetus to ravage the coast of Aethiopia as divine punishment. Andromeda is chained to a rock as a sacrifice to sate the monster, but is saved from death by Perseus, who marries her and takes her to Greece to reign as his queen.[1][2]

Her name is the Latinized form of the Greek Ἀνδρομέδα (Androméda) or Ἀνδρομέδη (Andromédē) 'ruler of men', from ἀνήρ, ἀνδρός (anēr, andrós) meaning 'man, husband, human being', and μέδω (medō) 'I protect, rule over'.

As a subject, Andromeda has been popular in art since classical times; it is one of several Greek myths of a Greek hero's rescue of the intended victim of an archaic hieros gamos (sacred marriage), giving rise to the "princess and dragon" motif. From the Renaissance, interest revived in the original story, typically as derived from Ovid's Metamorphoses (4.663ff).

Mythology

In Greek mythology Andromeda is the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, king and queen of ancient Ethiopia. Her mother Cassiopeia foolishly boasts that she is more beautiful than the Nereids,[3][4] a display of hubris by a human that is unacceptable to the gods. To punish the queen for her arrogance, Poseidon floods the Ethiopian coast and sends a sea monster named Cetus to ravage the kingdom's inhabitants. In desperation, King Cepheus consults the oracle of Ammon, who announces that no respite can be found until the king sacrifices his daughter, Andromeda, to the monster. She is thus chained to a rock by the sea to await her death.

Perseus is just then flying near the coast of Ethiopia on his winged sandals, having slain the Gorgon Medusa and carrying her severed head, which instantly turns to stone any who look at it. Upon seeing Andromeda bound to the rock, Perseus falls in love with her, and he secures Cepheus' promise of her hand in marriage if he can save her. Perseus kills the monster with the magical sword he had used against Medusa, saving Andromeda. Preparations are then made for their marriage, in spite of her having been previously promised to her uncle, Phineus. At the wedding, a quarrel between the rivals ends when Perseus shows Medusa's head to Phineus and his allies, turning them to stone.[5][6][7]

Andromeda follows her husband to his native island of Serifos, where he rescues his mother Danaë. They next go to Argos, where Perseus is the rightful heir to the throne. After accidentally killing Argos' king, his grandfather Acrisius, however, Perseus chooses to become king of neighboring Tiryns instead. Perseus and Andromeda have seven sons: Perses (who, according to folk etymology, is the ancestor of the Persians), Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, Electryon, and Cynurus as well as two daughters, Autochthe and Gorgophone. Their descendants rule Mycenae from Electryon down to Eurystheus, after whom Atreus attains the kingdom. The great hero Heracles (Hercules in Roman mythology) is also a descendant, his mother Alcmene being Electryon's daughter, while (like his grandfather Perseus) his father is the god Zeus.[8][9] The goddess Athena (or her Roman version Minerva) places Andromeda in the northern sky at her death as the constellation Andromeda, along with Perseus and her parents Cepheus and Cassiopeia, in commemoration of Perseus' bravery in fighting the sea monster Cetus.[10][11]

Variants of this story include:

- A 6th century BC vase painting shows Perseus throwing stones at Cetus instead of using his sword (right).

- Images from Classical antiquity often show Andromeda bound to two posts instead of to a rock (see example above).

- In Hyginus's account (Fabulae, 64) Perseus does not ask for Andromeda's hand in marriage before saving her, and when he afterwards intends to keep her for his wife, both her father Cepheus and her uncle Phineas plot against him, and Perseus resorts to using Medusa's head to turn them to stone.

- The primary Classical sources have Perseus kill Cetus with his magical sword, even though he also carries Medusa's head, which could easily turn the monster to stone (and Perseus does use Medusa's head for this purpose in other situations). The earliest straightforward account of Perseus using Medusa's head against Cetus, however, is from the later 2nd century AD satirist Lucian (The Hall, 22)[12]

- The 12th century Byzantine writer John Tzetzes, in his Scholiast (notes) on Lycophron's Alexandra (836), says that Cetus swallows Perseus, who kills the monster by hacking his way out with his sword.

- Conon (Narrations, 40) places the story in Joppa (Iope or Jaffa, on the coast of modern Israel), and seeks to rationalize the myth by making Andromeda's uncles Phineus and Phoinix rivals for her hand in marriage; her father Cepheus contrives to have Phoinix abduct her in a ship named Cetos from a small island she visits to make sacrifices to Aphrodite, and Perseus, sailing nearby, intercedes and destroys Cetos and its crew, who are "petrified by shock" at his bravery. Conon thus explains away all the exotic and magical elements of the story.

Ethnicities of Andromeda

Andromeda was the daughter of the king and queen of Ethiopia (Aithiopia/Aethiopia), which ancient Greeks located at the edge of the world of the lands south of Egypt (Nubia). The term Aithiops was generally applied to Nubians and other peoples who dwelt above the equator, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, being derived from the Greek words αἴθω and ὤψ (aitho 'I burn' + ops 'face'), translating as burnt-face in noun form and red-brown in adjectival form, as a reference to the Black African natives of the Kingdom of Kush.[13] Homer says the Ethiopians live "at the world's end, and lie in two halves, the one looking West and the other East,"[14] an idea echoed by Ovid, who located Ethiopia next to India, close to where the sun rises each day.[15] The 5th century BC historian Herodotus writes that "Where south inclines westwards, the part of the world stretching farthest towards the sunset is Ethiopia", and also included a plan by Cambyses II of Persia to invade Ethiopia (Kush)[16]

By the 1st century BC a rival location for Andromeda's story had been established, however: an outcrop of rocks near the harbor of the ancient port city of Joppa (Iope or Jaffa, today part of Tel Aviv, Israel) had become associated with the place of Andromeda's chaining and rescue, as reported by Pliny the Elder,[17] the traveler Pausanias,[18] the geographer Strabo,[19] and the historian Josephus.[20] A case has been made that this new version of the myth was exploited to enhance the fame and serve the local tourist trade of Joppa, which also became connected with the biblical story of Jonah featuring yet another huge sea creature.[21][22] This was, of course, at odds with Andromeda's African origins, adding to the confusion already surrounding her ethnicity, as reflected in 5th century Greek vase images showing Andromeda attended by dark-skinned African servants and wearing clothing that would have looked foreign to Greeks, yet with light skin[23]

Elizabeth McGrath, in her article The Black Andromeda,[24] discusses the tradition, as promoted by the influential Roman poet Ovid, of Andromeda being a dark-skinned woman of either Ethiopian or Indian origin. In his Heroides Ovid has Sappho explain to Phaon: "though I'm not pure white, Cepheus's dark Andromeda/charmed Perseus with her native color./White doves often choose mates of different hue/and the parrot loves the black turtle dove";[25] the Latin word fuscae Ovid uses here for "dark Andromeda" refers to the color black or brown. Elsewhere he says that Perseus brought Andromeda from "darkest" India [26] and declares “Nor was Andromeda’s color any problem/to her wing-footed aerial lover”[27] adding that “White suits dark girls; you looked so attractive in white, Andromeda”.[28] Ovid's account of Andromeda's story[29] follows Euripides' play Andromeda in having Perseus initially mistake the chained Andromeda for a statue of marble, which has been taken to mean she was light-skinned; but since statues in Ovid's time were commonly painted to look like living people, her skin tone could have been of any color.[30]

The Aethiopica, a Greek romance attributed to the 3rd century AD writer Heliodorus of Emesa, reflects the ambiguity between dark-skinned and light-skinned Andromedas in Late Antiquity. In the kingdom of Meroë (modern Sudan), Queen Persinna gives birth to her daughter, Chariclea who, despite having black parents, is born with white skin. The mother's explanation is that, during the moment of conception, she was gazing at a picture of a white-skinned Andromeda "brought down by Perseus naked from the rock, and so by mishap engendered presently a thing like to her."[31] After being long separated from her parents, living in Egypt and Greece, Princess Chariclea returns home with her lover Theagnes and proves both her heritage and her mother's story as true by showing her parents a single black spot upon her elbow. Like the mythical Andromeda, Chariclea thus 'passes' as a member of the Greek/Roman world as well as of her African birthplace.

This ambiguity is also reflected in a description by the 2nd century AD sophist Philostratus of a painting depicting Perseus and Andromeda.[32] He emphasizes the painting's Ethiopian setting, and notes that Andromeda "is charming in that she is fair of skin though in Ethiopia," in clear contrast to the other "charming Ethiopians with their strange coloring and their grim smiles" who have assembled to cheer Perseus in this picture.

Through the centuries, Ovid's descriptions of Andromeda and/or other authors' references to her African/Indian origins have influenced some Western artists, but not the majority. The alternative tradition of Andromeda's story taking place at Joppa (on the coast of modern Israel) suggested that she was of light complexion to some artists, while others simply followed the tendency of artists everywhere to make the main subjects of their works look like themselves and the people around them. Roman frescoes from Pompeii show light-skinned Andromedas, for instance, but a 2nd-3rd century AD Roman mosaic found at Zeugma in modern Turkey shows her with darker skin tones, which would be more common in the Middle East (see illustrations). A few Renaissance and Baroque artists, such as Piero di Cosimo, Titian, Giorgio Vasari, and Abraham van Diepenbeeck, painted Andromedas with darker or dusky-colored skin tones (see Gallery), but Ovid's tradition was not continued by their contemporaries or later artists.

Cultural references

Constellations

Andromeda is represented in the Northern sky by the constellation Andromeda, which contains the Andromeda Galaxy.

Several constellations are associated with the myth. Viewing the fainter stars visible to the naked eye, the constellations are rendered as:

- A maiden (Andromeda) chained up, facing or turning away from the ecliptic.

- A warrior (Perseus), often depicted holding the head of Medusa, next to Andromeda.

- A huge man (Cepheus) wearing a crown, upside down with respect to the ecliptic.

- A smaller figure (Cassiopeia) next to the man, sitting on a chair; as it is near the pole star, it may be seen by observers in the Northern Hemisphere through the whole year, although sometimes upside down.

- A whale or sea monster (Cetus) just beyond Pisces, to the south-east.

- The flying horse Pegasus, who was born from the stump of Medusa's neck after Perseus had decapitated her.

- The paired fish of the constellation Pisces, that in myth were caught by Dictys the fisherman who was brother of Polydectes, king of Seriphos, the place where Perseus and his mother Danaë were stranded.

In literature and theater

- Sophocles, Andromeda (5th century BC), lost tragedy except for fragments

- Euripides, Andromeda (412 BC), lost tragedy except for fragments; parodied by Aristophanes in his comedy Thesmophoriazusae (411 BC) and influential in the ancient world

- George Chapman's poem in Heroic couplets Andromeda liberata, Or the nuptials of Perseus and Andromeda, written for the 1614 wedding of the Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset and Frances Howard Frances Howard

- Ludovico Ariosto's influential epic poem Orlando Furioso (1516-1532) features a pagan princess named Angelica who at one point is in exactly the same situation as Andromeda, chained naked to a rock on the sea as a sacrifice to a sea monster, and is saved at the last minute by the Saracen knight Ruggiero.

- Lope de Vega's play El Perseo (1621)

- Pierre Corneille's verse play Andromède (1650), popular for its stage machinery effects, including Perseus astride Pegasus as he battles the sea monster, the success of which helped inspire Jean-Baptiste Lully's opera Persée.[33]

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca's play Las Fortunas de Perseo y Andrómeda (1653)

- John Weaver, Perseus and Andromeda (1716), a pantomimic entertainment

- John Keats' 1819 sonnet On the Sonnet compares the restricted sonnet form to the bound Andromeda as being "Fetter’d, in spite of pained loveliness"

- In Moby-Dick (1851), Herman Melville's narrator Ishmael discusses the Perseus and Andromeda myth in two chapters. Chapter 55, "Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales," mentions depictions of Perseus rescuing Andromeda from Cetus in artwork by Guido Reni and William Hogarth. In Chapter 82, "The Honor and Glory of Whaling," Ishmael recounts the myth and says that the Romans found a giant whale skeleton in Joppa that they believed to be the skeleton of Cetus.[34]

- James Robinson Planché and Charles Dance's Victorian burlesque, The Deep deep sea, or Perseus and Andromeda; an original mythological, aquatic, equestrian burletta in one act (1857)

- Charles Kingsley's free verse poem retelling the myth, Andromeda (1858)

- William Brough's Victorian burlesque Perseus and Andromeda, or, The Maid and the Monster: A Classical Extravaganza (1861)

- William Morris retells the story of Perseus and Andromeda in his epic poem The Earthly Paradise (1868) April: The Doom of King Acrisius

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Andromeda (1879)

Now Time's Andromeda on this rock rude,

With not her either beauty's equal or

Her injury's, looks off by both horns of shore,

Her flower, her piece of being, doomed dragon's food.

Time past she has been attempted and pursued

By many blows and banes; but now hears roar

A wilder beast from West than all were, more

Rife in her wrongs, more lawless, and more lewd.

Her Perseus linger and leave her tó her extremes?—

Pillowy air he treads a time and hangs

His thoughts on her, forsaken that she seems,

All while her patience, morselled into pangs,

Mounts; then to alight disarming, no one dreams,

With Gorgon's gear and barebill, thongs and fangs.

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Poems_of_Gerard_Manley_Hopkins/Andromeda

- Gerard Manley Hopkins' sonnet Andromeda (1879) (see box) has invited many interpretations[35]

- Julia Constance Fletcher (who wrote under the pseudonym George Fleming), Andromeda, a Novel (1885)

- Robert Williams Buchanan's novel Andromeda, An Idyl of the Great River (1901), updates the myth using characters in a 19th-century fishing community on the River Thames

- Richard Le Gallienne's prose version of Ovid's account, Perseus and Andromeda, A Retelling (1902)

- British poet, novelist and journalist Alphonse Courlander's (1881-1914) long poem Perseus and Andromeda in 1903

- Carlton Dawe's 1909 novel The New Andromeda (published in America as The Woman, the Man, and the Monster) retells the Andromeda story in a modern setting

- Muriel Stuart's closet drama Andromeda Unfettered (1922), featuring: Andromeda, "the spirit of woman"; Perseus, "the new spirit of man"; a chorus of "women who desire the old thrall"; and a chorus of "women who crave the new freedom"

- Robert Nichols' short story Perseus and Andromeda (1923) satirically retells the story in two contrasting styles

- In her novel The Sea, the Sea (1978), Iris Murdoch uses the Andromeda myth, as presented in a reproduction of Titian's painting Perseus and Andromeda, to reflect the character and motives of her characters

- Michael McClure's poem Fragments of Perseus (1983) "presents fragments of an imaginary journal by Perseus, son of Zeus and Danae, slayer of the snake-haired Medusa, and husband of Andromeda"

- Andromeda is the main character in Harry Turtledove's 1999 short story Miss Manners' Guide to Greek Missology, a satire filled with role reversals, puns, and deliberate anachronisms relating to pop culture[36]

- The main character in Jodi Picoult's My Sister's Keeper (2004) is named Andromeda, linking her parents' expecting her to sacrifice organs to keep her sister alive to the mythical Andromeda who was sacrificed by her parents

- In Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson & the Olympians series, the cruise ship Percy and Annabeth first board in The Sea of Monsters that is controlled by Luke and his group of half-bloods supporting the Titan Lord Kronos is called the Princess Andromeda, and bears a figurative masthead at the front of the ship of the princess in a Greek chiton with an expression of terror on her face.

In music

- Claudio Monteverdi, Andromeda (1618-1620), opera; the libretto exists but the music has been lost

- Jean-Baptiste Lully, Persée (1682), tragédie lyrique in 5 acts

- Georg Philipp Telemann, Perseus und Andromeda (1704), opera in 3 acts

- Antonio Maria Bononcini, Andromeda (1707), cantata for 4 voices and orchestra

- Andromeda liberata (1726), a pasticcio-serenata on the subject of Perseus freeing Andromeda, made as a collective tribute to the visiting Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni by at least five composers working in Venice, including Vivaldi

- Louis Antoine Lefebvre, Andromède (1762?), cantata for solo voice and orchestra

- Giovanni Piasiello, Andromeda (1773), 3-act opera

- Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, Symphony in F (Perseus' Rescue of Andromeda) and Symphony in D (The Petrification of Phineus and his Friends), Nos. 4 and 5 of his Symphonies after Ovid's Metamorphoses (ca. 1781)

- Augusta Holmès, Andromède (1883), symphonic poem

- Guillaume Lekeu, Andromède (1891), cantata for 4 voices, chorus & orchestra

- Cyril Rootham, Andromeda (1905), a musical setting of Charles Kingsley's poem Andromeda

- Jacques Ibert, Persée et Andromède, ou le Plus heureux des trois (1929), opera in 2 acts

- Jose Antonio Bottiroli, Andrómeda, Micro-sorrow I in D minor B96 for piano (1984)[37]

- Salvatore Sciarrino, Perseo e Andromeda (1990), opera in one act for 4 voices and synthesized sound

- Caroline Mallonée, Portraits of Andromeda for cello and string orchestra (2019)[38]

- Weyes Blood, “Andromeda” on her album Titanic Rising (2019)

- Ensiferum, “Andromeda” on the album Thalassic (2020)[39]

In films

- Perseus (1973), a short animated film by Soviet animator Alexandra Snezhko-Blotskaya, pits Perseus' natural kindness against the god Hermes' greed, and presents the Ethiopian Andromeda as dark-skinned (while making Perseus blond).

- The 1981 film Clash of the Titans is loosely based on the story of Perseus, Andromeda, and Cassiopeia, and makes quite a few changes to the original myth. In the film Cassiopeia boasts that her daughter is more beautiful than the single Nereid Thetis, rather than the Nereids as a group. Andromeda and Perseus meet and fall in love after he saves her soul from the enslavement of Thetis' "son" Calibos (a made-up character introduced to provide Perseus with a dramatic foil) and before he slays Medusa, whereas in the myth they first meet when Perseus finds Andromeda chained to the rock as he is returning home from having already slain Medusa. In the film the monster is called a kraken (which was the name of a giant squid-like sea monster in Norse mythology) and looks very different from the whale-like Cetos of Greek mythology. Perseus defeats the sea monster by showing it Medusa's face to turn it into stone, even though the Classical sources typically say he killed the monster with his magical sword. In the film Perseus tames and rides the flying horse Pegasus, which in Classical mythology was done by the hero Bellerophon. Perseus' use of Pegasus, along with his turning the monster to stone, was added to Perseus' myth in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Also, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. criticizes this film (and its 2010 remake) for using white actresses to portray the Ethiopian princess Andromeda.[40]

- In the Japanese anime Saint Seiya (1986- ), the character Shun represents the Andromeda constellation using chains as his main weapons, reminiscent of Andromeda being chained before she was saved by Perseus. In order to attain the Andromeda Cloth, he was chained between two large pillars of rock and he had to overcome the chains before the tide came in and killed him, also reminiscent of this myth.

- Andromeda appears in Disney's Hercules: The Animated Series (1998-1999) as a new student of "Prometheus Academy" which Hercules and other characters from Greek mythology attend.

- The main character in My Sister's Keeper's (2010) is named Andromeda, linking her parents' plan for her to sacrifice organs to keep her sister alive to the mythical Andromeda who was sacrificed by her parents.

- Andromeda is featured in the 2010 film Clash of the Titans, a remake of the 1981 version which strays so much further from the myth's ancient sources, and Greek mythology in general, that there is little reason to make comparisons. The 2012 sequel, Wrath of the Titans, draws more from Norse mythology's twilight of the gods (Ragnarök), than Greek mythology.

In art

Andromeda, and her role in the popular myth of Perseus, has been the subject of numerous ancient and modern works of art, where she is represented as a bound and helpless, typically beautiful, young woman placed in terrible danger, who must be saved through the unswerving courage of a hero who loves her: (see Gallery)

- Although ancient artists at first presented her fully clothed, nude images of Andromeda started appearing during Classical antiquity, and by the Renaissance the chained nude figure of Andromeda, either alone or being rescued, had become the standard, as seen in works by Titian, Joachim Wtewael, Cesari, Passerotti, Veronese, Rubens, Bertin, Boucher, van Loo, Moreau, Stanhope, and Burne-Jones.

- Rather than dwelling on Andromeda's physical beauty, artists such as Rembrandt, Fetti, Chassériau, Delacroix, Doré, Leighton, and (satirically) Vallotton, have focused on her terror and vulnerability as she awaits the monster.

- Some artists such as Piero di Cosimo, Jan Keynooghe, Jacob Matham, and Pierre Mignard, have shown Andromeda in relation to her parents and onlookers.

Andromeda was a popular subject for artists especially in the Renaissance and Baroque eras, followed by a resurgence of interest in her myth in the 19th century, but since then artists have shown much less interest in this subject.

Other Art Traditions Inspired by the Andomeda Myth:

- The legend of Saint George and the Dragon, in which a courageous knight rescues a princess from a monster (with clear parallels to the Andromeda myth), became a popular subject for art in the Late Middle Ages, and artists drew from both traditions. One result is the idea of having Perseus riding the flying horse Pegasus when fighting the sea monster (as seen in paintings by Matham, Passerotti, Cesari, Wtewael, Rubens, Mignard, Bertin, and Leighton below), despite classical sources consistently stating that he flew using winged sandals and connecting Pegasus to the hero Bellerophon's adventures.

- Ludovico Ariosto's influential epic poem Orlando Furioso (1516-1532) features a pagan princess named Angelica who at one point is in exactly the same situation as Andromeda, chained naked to a rock on the sea as a sacrifice to a sea monster, and is saved at the last minute by the Saracen knight Ruggiero. Artists were drawn to this subject for the same reasons they appreciated the Andromeda myth, and images of Angelica and Ruggiero (or Roggiero/Roger) are often hard to distinguish from those of Andromeda and Perseus

Gallery

-

Piero di Cosimo, Perseus Freeing Andromeda, ca. 1510

-

Titian, Perseus and Andromeda, 1554-1556

-

Giorgio Vasari, Perseus and Andromeda, 1570

-

Bartolomeo Passerotti, Perseus Freeing Andromeda, between 1572 and 1575

-

Paolo Veronese, Perseus rescuing Andromeda, between 1576 and 1578

-

Jacob Matham, Andromeda, 1597

-

Giuseppe Cesari, Perseus and Andromeda, 1602

-

Joachim Wtewael, Perseus Releases Andromeda, 1611

-

Domenico Fetti, Andromeda and Perseus, ca. 1621-1622

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Perseus and Andromeda, ca. 1622

-

Pierre Mignard, The Liberation of Andromeda, 1679

-

Domenico Guidi, Andromeda and the Sea Monster, 1694

-

Nicolas Bertin (1667-1736), Perseus Freeing Andromeda

-

François Boucher, Andromeda, 1732

-

Charles André van Loo, Perseus and Andromeda, between 1735 and 1740

-

Théodore Chassériau, Andromeda Chained to the Rock by the Nereids, 1840

-

Julius Troschel, Perseus and Andromeda, 1840-1850

-

Eugène Delacroix, Perseus and Andromeda, ca. 1853

-

Paul Gustave Doré, Andromeda, 1869

-

Gustave Moreau, Perseus and Andromeda, 1870

-

Edward Poynter, Andromeda, 1869

-

Edward Burne-Jones, Perseus and Andromeda, 1876

-

John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, Andromeda, 1886

-

Félix Vallotton, Perseus Killing the Dragon, 1910

See also

Notes

- ^ Who's Who in Classical Mythology, Michael Grant & John Hazel, Oxford University Press, 1973, 1993, p. 31, ISBN 0-19-521030-1.

- ^ Kerenyi, Carl (1997). The heroes of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson. pp. 52–53. ISBN 050027049X.

- ^ Both Catasterismi (1.17) and De Astronomica (2.9-12) cite Sophocles' lost play Andromeda as their source for this.

- ^ Hyginus (Fabulae 64) says that Cassoipeia was boasting of her daughter Andromeda's beauty rather than of her own.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses (4.663-5.235)

- ^ Apollodorus, Library (2.35-44)

- ^ Marcus Manilius, Astronomica (5.538-634)

- ^ Apollodorus, Library (2.45-59)

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses (5.236-249)

- ^ Pseudo-Eratosthenes, Catasterismi (1.17)

- ^ De Astronomica (2.9-12)

- ^ Lucian describes a painting of "a story half Argive, half Ethiopian. Perseus slays the sea-monster, and sets Andromeda free; it will not be long ere he leads her away as his bride; an episode, this, in his Gorgon expedition. The artist has given us much in a small space: maiden modesty, girlish terror, are here portrayed in the countenance of Andromeda, who from her high rock gazes down upon the strife, and marks the devoted courage of her lover, the grim aspect of his bestial antagonist. As that bristling horror approaches, with awful gaping jaws, Perseus in his left hand displays the Gorgon's head, while his right grasps the drawn sword. All of the monster that falls beneath Medusa's eyes is stone already; and all of him that yet lives the scimitar hews to pieces."

- ^ Thompson, Lloyd A. (1989). Romans and blacks. Taylor & Francis. p. 57. ISBN 0-415-03185-0.

- ^ Odyssey 1.22-24; Homer also established a long-standing literary tradition that Ethiopia was an idyllic land of plenty where the gods attended feasts (see: Bonnie MacLachlan, "Feasting with Ethiopians: Life on the Fringe," Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series, Vol. 40, No. 1 (1992), pp. 15-33 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/20547123))

- ^ Metamorphoses 1.1076-1084

- ^ Histories 3.114; 3.94; 7.70

- ^ Natural History 5.69

- ^ 4.35.9

- ^ 4.35.9 and 16.2.28

- ^ Jewish War 3.9.3

- ^ Paul Harvey Jr., "The death of mythology: the case of Joppa," Journal of Early Christian Studies , January 1994, Vol. 2 Issue: Number 1 p 1-14

- ^ Ted Kaizer, "Interpretations of the myth of Andromeda at Iope," Syria, T. 88 (2011), pp. 323-339 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/41682313)

- ^ https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153843

- ^ Elizabeth McGrath, "The Black Andromeda", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes Vol. 55 (1992), pp. 1-18 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/751417)

- ^ xv, 35-38

- ^ Ars Amatoria 1.53

- ^ Ars Amatoria 2.643-44

- ^ Ars Amatoria 3.191-192

- ^ Metamorphoses 4.665ff

- ^ Koch-Brinkmann, Ulrike; Dreyfus, Renée; Brinkmann, Vinzenz (2017). Gods in color : polychromy in the ancient world. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Legion of Honor. ISBN 978-3-7913-5707-2. OCLC 982089362.

- ^ Heliodorus, Aethiopica book 4

- ^ Imagines 1.29

- ^ Wes Williams, For Your Eyes Only”: Corneille’s View of Andromeda. Classical Philology , Vol. 102, No. 1, Special Issues on Ekphrasis. Edited by Shadi Bartsch and Jaś Elsner (January 2007), pp. 110-123 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/521136)

- ^ Melville, Herman (1851). Moby-Dick.

- ^ Paul L. Mariani, "Hopkins' "Andromeda" and the New Aestheticism," Victorian Poetry, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1973), pp. 39-54

- ^ Turtledove, Harry (1999). "Myth Manners' Guide to Greek Missology #1: Andromeda and Persueus". In Friesner, Esther (ed.). Chicks 'n Chained Males. Riverdale, NY: Baen Books.

- ^ Banegas, Fabio (2017). Jose Antonio Bottiroli Vol. II - Complete Piano Works (First ed.). The Library of Congress (LC): Golden River Music. p. 127. ISMN 979-0-3655-2418-1. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ https://news.wbfo.org/post/buffalo-composer-puts-andromeda-constellation-myth-and-meteors-music

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgF38ZQJAPU

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Was Andromeda Black?, Roots (17 Feb 2014) https://www.theroot.com/was-andromeda-black-1790874592

Sources

For Full Text and Translations of Source Materials and Articles on Mythology:

- Perseus Digital Library (Tufts University) https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/

- Theoi Greek Mythology https://www.theoi.com/

Primary Greek and Roman sources:

- Apollodorus, Library (Bibliotheca) 2.4.3–5 (online English translation by James George Frazer (1921): https://www.theoi.com/Text/Apollodorus1.html)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.668–5.235 (online English translation by Brooks More (1922): https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidMetamorphoses1.html)

Comprehensive Studies of the Perseus myth:

- Edwin Hartland, The Legend of Perseus: A Study of Tradition in Story, Custom and Belief, 3 vols. (1894-1896) ISBN 1481035738 (available online at: https://archive.org/details/legendofperseuss01hart/page/n6/mode/2up)

- Daniel Ogden, Perseus (Routledge, 2008) ISBN 0415427258