Dead Poets Society

| Dead Poets Society | |

|---|---|

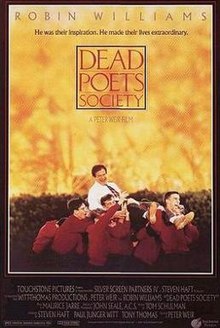

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Written by | Tom Schulman |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | Robin Williams |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | William Anderson |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution (United States theatrical and worldwide home video) Warner Bros. (International theatrical release only)[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 128 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $16.4 million[2] |

| Box office | $235.9 million[3] |

Dead Poets Society is a 1989 American drama film directed by Peter Weir, written by Tom Schulman, and starring Robin Williams. Set in 1959 at the fictional elite conservative boarding school Welton Academy,[4] it tells the story of an English teacher who inspires his students through his teaching of poetry.

The film was a commercial success and received numerous accolades, including Academy Award nominations for Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Actor for Robin Williams. The film won the BAFTA Award for Best Film,[5] the César Award for Best Foreign Film and the David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Film. Schulman received an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for his work.

Plot

In 1959, Todd Anderson begins his junior year of high school at Welton Academy, an all-male prep school in Vermont. Assigned one of Welton's most promising students, senior Neil Perry, as his roommate, he meets his friends: Knox Overstreet, Richard Cameron, Steven Meeks, Gerard Pitts, and Charlie Dalton.

On the first day of classes, the boys are surprised by the unorthodox teaching methods of new English teacher, John Keating. A Welton alumnus himself, Keating encourages his students to "make your lives extraordinary", a sentiment he summarizes with the Latin expression carpe diem ("seize the day").

Subsequent lessons include Keating having the students take turns standing on his desk to demonstrate ways to look at life differently, telling them to rip out the introduction of their poetry books which explains a mathematical formula used for rating poetry, and inviting them to make up their own style of walking in a courtyard to encourage their individualism. Keating's methods attract the attention of strict headmaster Gale Nolan.

Upon learning that Keating was a member of the unsanctioned Dead Poets Society while at Welton, Neil restarts the club and he and his friends sneak off campus to a cave where they read poetry. As the school year progresses, Keating's lessons and their involvement with the club encourage them to live their lives on their own terms. Knox pursues Chris Noel, an attractive cheerleader who is dating Chet Danburry, a football player from a local public school whose family is friends with his.

Neil discovers his love of acting and gets the role as Puck in a local production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, despite the fact that his domineering father wants him to attend Harvard to study medicine. Meanwhile, Keating helps Todd come out of his shell and realize his potential when he takes him through an exercise in self-expression, resulting in his composing a poem spontaneously in front of the class.

Charlie publishes an article in the school newspaper in the club's name suggesting that girls be admitted to Welton. Nolan paddles Charlie to coerce him into revealing who else is in the Dead Poets Society, but he resists. Nolan also speaks with Keating, warning him that he should discourage his students from questioning authority. Keating admonishes the boys in his manner, warning that one must assess all consequences.

Neil becomes devastated after his father discovers his involvement in the play and demands he quit on the eve of the opening performance. He goes to Keating, who advises him to stand his ground and prove to his father that his love of acting is something he takes seriously. Neil's father unexpectedly shows up at the performance. He angrily takes Neil home and has him withdrawn from Welton and enrolled in a military academy. Lacking any support from his concerned mother, and unable to explain how he feels to his father, a distraught Neil commits suicide.

Nolan investigates Neil's death at the request of the Perry family. Cameron blames Neil's death on Keating to escape punishment for his own participation in the Dead Poets Society, and names the other members. Confronted by Charlie, Cameron urges the rest of them to let Keating take the fall. Charlie punches Cameron and is expelled. Each of the boys is called to Nolan's office to sign a letter attesting to the truth of Cameron's allegations, even knowing they are false. When Todd's turn comes, he is reluctant to sign, but does so after seeing that the others have complied and succumbs to his parents' pressure.

Keating is fired and Nolan takes over teaching the class, with the intent of adhering to traditional Welton rules. Keating interrupts the class to gather his leftover belongings. As he leaves, Todd reveals to Keating that the boys were intimidated into signing the paper that sealed his fate, and he assures Todd that he believes him. Nolan threatens to expel Todd. Todd stands up on his desk, with the words "O Captain! My Captain!", which prompts Nolan to threaten him again. The other members of the Dead Poets Society (except for Cameron), as well as several other students in the class, do the same, to Nolan's fury and Keating's pleased surprise. Keating thanks the boys and departs.

Cast

- Robin Williams as John Keating

- Robert Sean Leonard as Neil Perry

- Ethan Hawke as Todd Anderson

- Josh Charles as Knox Overstreet

- Gale Hansen as Charlie Dalton

- Norman Lloyd as Headmaster Gale Nolan

- Kurtwood Smith as Thomas Perry

- Dylan Kussman as Richard Cameron

- Allelon Ruggiero as Steven Meeks

- James Waterston as Gerard Pitts

- Alexandra Powers as Chris Noel

- Leon Pownall as George McAllister, Latin teacher[6]

- George Martin as Dr. Hager, mathematics teacher

- Carla Belver as Mrs. Perry

- Jane Moore as Mrs. Danburry

- Kevin Cooney as Joe Danburry

- Colin Irving as Chet Danburry

- Matt Carey as Kurt Hopkins

- John Cunningham as Mr. Anderson

- Lara Flynn Boyle as Ginny Danburry (scenes deleted)

Production

Development

Peter Weir had been eager to follow up his two US breakthrough hits with Harrison Ford, Witness and The Mosquito Coast,[dubious – discuss] with a romantic comedy starring Gérard Depardieu as a Frenchman who marries an American for convenience called Green Card. Depardieu was in high demand following his success in the Provençal drama Jean de Florette and Weir was advised he would have to wait a year for his availability.[7]

In late 1988, Weir met with Jeffrey Katzenberg at Disney (which produced the movie via Touchstone Pictures), who suggested Weir read a script recently received. On a flight back to Sydney, Weir was captivated and six weeks later returned to Los Angeles to cast the principal characters.[8]

The original script was written by Tom Schulman, based on his experiences at the Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville, Tennessee, particularly with his inspirational teacher Samuel Pickering.[9][10] In Schulman's manuscript, Keating had been ill, slowly dying of Hodgkin lymphoma with a scene showing him on his deathbed in the hospital. This was removed by Weir who deemed it unnecessary, claiming this would focus audiences on Keating's illness and not on what he stood for.[11]

Early notes on the script from Disney also suggested making the boys' passion dancing rather than poetry, as well as a new title, Sultans of Swing, focusing on the character of Mr. Keating rather than the boys themselves, but both were dismissed outright.[8]

Filming started in the winter of 1988 and took place at St. Andrew's School and the Everett Theatre in Middletown, Delaware, and at locations in New Castle, Delaware, and in nearby Wilmington, Delaware.[12] During the shooting, Weir requested the young cast not to use modern slang, even off camera.[13]

Casting

Liam Neeson originally won the part of John Keating before Peter Weir took over direction from Jeff Kanew.[14] Other actors considered were Dustin Hoffman,[15] Tom Hanks and Mickey Rourke.[16]

Filming

During filming, Robin Williams used to crack many jokes on set, which Ethan Hawke found incredibly irritating. For the scene where Todd Anderson is spontaneously incited by John Keating to make a poem in front of the class, Williams apparently made a joke saying that Hawke was intimidating, which Hawke later realized was serious and that the joke referred to his earnestness and intensity as a young man. Ironically, Hawke's first agent signed with Hawke once Williams told him that Hawke would "do really well".[17]

Reception

Box office

The worldwide box office was reported as $235,860,579, which includes domestic grosses of $95,860,116.[3] The film's global receipts were the fifth highest for 1989, and the highest for dramas.[18]

Critical response

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 84% based on 61 reviews with an average score of 7.2/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Affecting performances from the young cast and a genuinely inspirational turn from Robin Williams grant Peter Weir's prep school drama top honors."[19] On Metacritic, the film received a score of 79 based on 14 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[20] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[21]

The Washington Post's reviewer called it "solid, smart entertainment", and praised Robin Williams for giving a "nicely restrained acting performance".[22] Vincent Canby of The New York Times also praised Williams' "exceptionally fine performance", while writing that "Dead Poets Society ... is far less about Keating than about a handful of impressionable boys".[4] Pauline Kael was unconvinced about the film, and its "middlebrow highmindedness", but praised Williams. "Robin Williams' performance is more graceful than anything he's done before [–] he's totally, concentratedly there – [he] reads his lines stunningly, and when he mimics various actors reciting Shakespeare there's no undue clowning in it; he's a gifted teacher demonstrating his skills."[23]

Roger Ebert's review gave the film two out of four stars. He criticized Williams for spoiling an otherwise creditable dramatic performance by occasionally veering into his onstage comedian's persona, and lamented that for a film set in the 1950s there was no mention of the Beat Generation writers. Additionally, Ebert described the film as an often poorly constructed "collection of pious platitudes ... The movie pays lip service to qualities and values that, on the evidence of the screenplay itself, it is cheerfully willing to abandon."[24]

On their Oscar Nomination edition of Siskel & Ebert, both Gene Siskel (who also gave the film a mixed review) and Ebert disagreed with Williams' Oscar nomination; Ebert said that he would have swapped Williams with either Matt Dillon for Drugstore Cowboy or John Cusack for Say Anything. On their If We Picked the Winners special in March 1990, Ebert chose the film's Best Picture nomination as the worst nomination of the year, believing it took a slot that could have gone to Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing.

Film historian Leonard Maltin wrote: "Well made, extremely well acted, but also dramatically obvious and melodramatically one-sided. Nevertheless, Tom Schulman's screenplay won an Oscar."[25]

John Simon, writing for National Review, said Dead Poets Society was the most dishonest film he had seen in some time.[26]

Accolades

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- John Keating – Nominated Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary." – #95

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – #52

The film was voted #52 on the AFI's 100 Years…100 Cheers list, a list of the top 100 most inspiring films of all time.[40]

The film's line "Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary." was voted as the 95th greatest movie quote by the American Film Institute.[41]

Legacy

After Robin Williams' death in August 2014, fans of his work used social media to pay tribute to him with photo and video reenactments of the film's final "O Captain! My Captain!" scene.[42]

Adaptations

Nancy H. Kleinbaum's novel Dead Poets Society (1989) is based on the movie.[43]

Stage play

A theatrical adaptation written by Tom Schulman and directed by John Doyle opened Off-Broadway on October 27, 2016, and ran through December 11, 2016.[44] Jason Sudeikis stars as John Keating[45] with Thomas Mann as Neil Perry, David Garrison as Gale Nolan, Zane Pais as Todd Anderson, Francesca Carpanini as Chris, Stephen Barker Turner as Mr. Perry, Will Hochman as Knox Overstreet, Cody Kostro as Charlie Dalton, Yaron Lotan as Richard Cameron, and Bubba Weiler as Steven Meeks.[46][47]

The production received a mixed review from The New York Times, with critic Ben Brantley calling the play "blunt and bland" and criticizing Sudeikis's performance, citing his lack of enthusiasm when delivering powerful lines.[48]

In 2018, the theatrical adaptation of the film, written by Tom Schulman and directed by Francisco Franco, premiered in Mexico. The Mexican actor Alfonso Herrera played the main character.[49]

Parodies

The ending of the film was parodied in the Saturday Night Live sketch "Farewell, Mr. Bunting", in which a student, upon climbing onto his desk, is decapitated by a ceiling fan.[50]

See also

- "The Changing of the Guard", a June 1, 1962 episode of The Twilight Zone starring Donald Pleasence as a retiring English teacher at a New England boys' school, who questions whether he has made a difference in the boys' lives.

- The Emperor's Club (2002), an American drama film set in a boys' preparatory school in the northeast.

References

- ^ a b "Dead Poets Society". BBFC. February 5, 1999. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society (1989)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on April 13, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "Dead Poets Society (1989) daily". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 16, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (June 2, 1989). "Dead Poets Society (1989) June 2, 1989 Review/Film; Shaking Up a Boys' School With Poetry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Film Film | BAFTA Awards". Awards.bafta.org. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "LitCharts". Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ King, James (2018). Fast Times and Excellent Adventures. London: Constable. p. 429. ISBN 9781472123725.

- ^ a b King, James (2018). Fast Times and Excellent Adventures. London: Constable. p. 430. ISBN 9781472123725.

- ^ "Real-life professor inspires 'Dead Poets' character". TimesDaily. Florence, AL, USA: Tennessee Valley Printing Co., Inc. Associated Press. July 10, 1989. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ Bill Henderson (January 12, 1992). "Robin Williams and Then Some". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ McCurrie, Tom (March 15, 2004). "Dead Poets Society's Tom Schulman on the Art of Surviving Hollywood". Writersupercenter.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2015.

- ^ Cormier, Ryan (August 12, 2014) [Originally published April 4, 2014]. "25 'Dead Poets Society' in Delaware facts". The News Journal. Pulp Culture. Wilmington, Delaware, USA: Gannett Company. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ King, James (2018). Fast Times and Wxcellent Adventures. London: Constable. p. 433. ISBN 9781472123725.

- ^ Meil, Eila (2005). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A. New York: McFarland. ISBN 9780786420179.

- ^ Brady, Celia (March 1989). "Bring Back the Kids: Hollywood's Littlest Stars and Biggest Egos in their Middle Ages". Spy: 107.

- ^ Walsh, Keri (2014). Mickey Rourke. London: Bloomsbury. p. 2. ISBN 9781844574308.

- ^ Bailey-Millado, Rob (August 30, 2021). "Ethan Hawke: Robin Williams was 'incredibly irritating' on 'Dead Poets' set". New York Post. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ "1989 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society Movie Reviews, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society reviews at Metacritic.com". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. August 19, 2011. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ Howe, Desson (June 9, 1989). "'Dead Poets Society'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Pauline Kael, Movie Love, pp. 153-157, reprinted from review that appeared in The New Yorker, June 26, 1989

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 9, 1989). "Dead Poets Society". Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. New York: Plume/Penguin. p. 328. ISBN 9780452289789. OCLC 183268110.

- ^ Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Film: Criticism 1982-2001. Applause Books. p. 225.

- ^ "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1990". BAFTA. 1990. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "The 1991 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "42nd DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Dead Poets Society – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1989 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "6th Warsaw Film Festival". Warsaw Film Festival. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "11th Annual Youth In Film Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ^ American Film Institute. "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 CHEERS". Afi.com. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ American Film Institute. "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 MOVIE QUOTES". Afi.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Robin Williams death: Jimmy Fallon fights tears, pays tribute with 'Oh Captain, My Captain'". August 13, 2014. Archived from the original on September 1, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Kleinbaum, N.H. (1989). Dead Poets Society. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0877-3. OCLC 71164757.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (February 29, 2016). "CSC to Stage World Premiere of Dead Poets Society". Playbill.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (August 16, 2016). "Jason Sudeikis to Star in Stage Version of 'Dead Poets Society'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (September 14, 2016). "Dead Poets Society Finds Its Complete Cast". Playbill.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (October 27, 2016). "The World Premiere of Dead Poets Society Begins Tonight". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (November 17, 2016). "Review: 'Dead Poets Society,' Starring Jason Sudeikis as the Idealistic Teacher". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 8, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "La sociedad de los poetas muertos". carteleradeteatro. March 5, 2018. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Silverberg, Nicole (May 23, 2016). "Behold, a New Classic 'SNL' Sketch". GQ. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

Further reading

- Munaretto, Stefan (2005). Erläuterungen zu Nancy H. Kleinbaum/Peter Weir, 'Der Club der toten Dichter' (in German). Hollfeld: Bange. ISBN 3-8044-1817-1.

External links

- 1989 films

- 1980s coming-of-age drama films

- 1980s teen drama films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American high school films

- American teen drama films

- 1980s English-language films

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- Films about educators

- Films about poetry

- Films about student societies

- Films about suicide

- Films about teacher–student relationships

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in Vermont

- Films shot in Delaware

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Touchstone Pictures films

- Films scored by Maurice Jarre

- Films directed by Peter Weir

- Films set in boarding schools

- 1989 drama films

- Films produced by Steven Haft

- 1980s American films