Education in Islam

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Education has played a central role in Islam since the beginnings of the religion, owing in part to the centrality of scripture and its study in the Islamic tradition. Before the modern era, education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran. For the first few centuries of Islam, educational settings were entirely informal, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema (religious scholars). Madrasas soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, which helped to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[1] Madrasas were devoted principally to study of Islamic law, but they also offered other subjects such as theology, medicine, and mathematics.[2] Muslims historically distinguished disciplines inherited from pre-Islamic civilizations, such as philosophy and medicine, which they called "sciences of the ancients" or "rational sciences", from Islamic religious sciences. Sciences of the former type flourished for several centuries, and their transmission formed part of the educational framework in classical and medieval Islam. In some cases, they were supported by institutions such as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, but more often they were transmitted informally from teacher to student.[1]

Etymology

In Arabic three terms are used for education. The most common term is ta'līm, from the root 'alima, which means knowing, being aware, perceiving and learning. Another term is Tarbiyah from the root of raba, which means spiritual and moral growth based on the will of God. The third term is Ta'dīb from the root aduba which means to be cultured or well accurate in social behavior.[3]

Education in pre-modern Islam

The centrality of scripture and its study in the Islamic tradition helped to make education a central pillar of the religion in virtually all times and places in the history of Islam.[1] The importance of learning in the Islamic tradition is reflected in a number of hadiths attributed to Muhammad, including one that instructs the faithful to "seek knowledge, even in China".[1] This injunction was seen to apply particularly to scholars, but also to some extent to the wider Muslims public, as exemplified by the dictum of Al-Zarnuji, "learning is prescribed for us all".[1] While it is impossible to calculate literacy rates in pre-modern Islamic societies, it is almost certain that they were relatively high, at least in comparison to their European counterparts.[1]

Education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran, either at home or in a primary school, which was often attached to a mosque.[1] Some students would then proceed to training in tafsir (Quranic exegesis) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), which was seen as particularly important.[1] Education focused on memorization, but also trained the more advanced students to participate as readers and writers in the tradition of commentary on the studied texts.[1] It also involved a process of socialization of aspiring scholars, who came from virtually all social backgrounds, into the ranks of the ulema.[1]

The Islamic Empire, spanning for almost 1,000 years, saw at least 60 major learning centers throughout the Middle East and North Africa, some of the most prominent among these being Baghdad in the East and Cordoba in the West.[4] For the first few centuries of Islam, educational settings were entirely informal, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema.[1] Madrasas soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, which helped to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[1] Nevertheless, instruction remained focused on individual relationships between students and their teacher.[1] The formal attestation of educational attainment, ijaza, was granted by a particular scholar rather than the institution, and it placed its holder within a genealogy of scholars, which was the only recognized hierarchy in the educational system.[1] While formal studies in madrasas were open only to men, women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation.[5][6] Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[5]

From the 8th century to the 12th century, the primary mode of receiving education in the Islamic world was from private tutors for wealthy families who could afford a formal education, not madrasas.[7] This formal education was most readily available to members of the caliphal court including the viziers, administrative officers, and wealthy merchants. These private instructors were well known scholars who taught their students Arabic, literature, religion, mathematics, and philosophy.[7] Islamic Sassanian tradition praises the idea of a 'just ruler' or a king learned in the ways of philosophy.[7] This concept of an 'enlightened philosopher-king' served as a catalyst for the spread of education to the populous.

Madrasas were devoted principally to the study of law, but they also offered other subjects such as theology, medicine, and mathematics.[2][8] The madrasa complex usually consisted of a mosque, boarding house, and a library.[2] It was maintained by a waqf (charitable endowment), which paid salaries of professors, stipends of students, and defrayed the costs of construction and maintenance.[2] The madrasa was unlike a modern college in that it lacked a standardized curriculum or institutionalized system of certification.[2]

Madrasa education taught medicine and pharmacology primarily on the basis of humoral pathology.[9] The Greek physician Hippocrates is credited for developing the theory of the four humors, also known as humoral pathology.[7][9] The humors influence bodily health and emotion and it was thought that sickness and disease stemmed from an imbalance in a person's humors, and health could only be restored by finding humoral equilibrium through remedies of food or bloodletting.[7][9] Each humor is thought to be related to a universal element and every humor expresses specific properties.[10] The interpenetration of the individual effects of each humor on the body are called mizādj.[10] Black Bile is related to the earth element and expresses cold and dry properties, yellow bile is related to fire and subsequently is dry and warm, phlegm is related to water and it expresses moist and cold properties, and blood is air displaying moist and warm qualities.[11]

To aid in medical efforts to fight disease and sickness, Ibn Sina also known as Avicenna, wrote the Canon of Medicine.[9] This was a five-book encyclopedia compilation of Avicenna's research towards healing illnesses, and it was widely used for centuries across Eurasia as a medical textbook.[9] Many of Avicenna's ideas came from al-Razi's al-Hawi.[12]

Muslims distinguished disciplines inherited from pre-Islamic civilizations, such as philosophy and medicine, which they called "sciences of the ancients" or "rational sciences", from Islamic religious sciences.[1] Sciences of the former type flourished for several centuries, and their transmission formed part of the educational framework in classical and medieval Islam.[1] In some cases, they were supported by institutions such as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, but more often they were transmitted informally from teacher to student.[1]

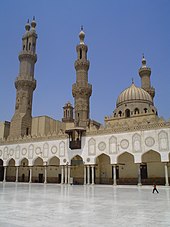

The University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859 AD, is listed in The Guinness Book Of Records as the world's oldest degree-granting university.[13] Scholars occasionally call the University of Al Quaraouiyine (name given in 1963), founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 859, a university,[14][15][16][17] although some scholars such as Jacques Verger writes that this is done out of scholarly convenience.[18] Several scholars consider that al-Qarawiyyin was founded[19][20] and run[21][22][23][24][25] as a madrasa until after World War II. They date the transformation of the madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin into a university to its modern reorganization in 1963.[26][27][21] In the wake of these reforms, al-Qarawiyyin was officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" two years later.[26] The Al-Azhar University was another early university (madrasa). The madrasa is one of the relics of the Fatimid caliphate. The Fatimids traced their descent to Muhammad's daughter Fatimah and named the institution using a variant of her honorific title Al-Zahra (the brilliant).[28] Organized instruction in the Al-Azhar Mosque began in 978.[29]

Theories of Islamic Education

Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas described the Islamic purpose of education as a balanced growth of the total personality through training the spirit, intellect, rational self, feelings and bodily senses such that faith is infused into the whole personality.[3]

One of the more prominent figures in the history of Islamic education, Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali studied theology and education on a theoretical level in the late 1000s, early 1100s CE. One of the ideas that Al-Ghazali was most known for was his emphasis on the importance of connecting educational disciplines on both an instructional and philosophical level.[30] With this, Al-Ghazali heavily incorporated religion into his pedagogical processes, believing that the main purpose of education was to prepare and inspire a person to more faithfully participate in the teachings of Islam.[31] Seyyed Hossein Nasr stated that, while education does prepare humankind for happiness in this life, "its ultimate goal is the abode of permanence and all education points to the permanent world of eternity".[3]

According to Islam, there are three elements that make up an Islamic education. These are the learner, knowledge, and means of instruction.[31][32] Islam posits that humans are unique among all of creation in their ability to have 'Aql (faculty of reason).[33] According to the Nahj al-Balagha, there are two kinds of knowledge: knowledge merely heard and that which is absorbed. The former has no benefit unless it is absorbed. The heard knowledge is gained from the outside and the other is absorbed knowledge means the knowledge that raised from nature and human disposition, referred to the power of innovation of a person.[34]

The Quran is the optimal source of knowledge in Islamic Education.[35] For teaching Quranic traditions, the Maktab as elementary school emerged in mosques, private homes, shops, tents, and even outside.[36][3] The Quran is studied by both men and women in the locations listed above, however, women haven't always been permitted in study in mosques. The main place of study for women before the mosques changed their ideology was in their own homes or the homes of others. One well-known woman that allowed others into her home to teach the Quranic traditions was Khadija, Muhammad's wife.[37]

The Organization of the Islamic Conference has organized five conferences on Islamic education: in Mecca (1977), Islamabad (1980), Dhaka (1981), Jakarta (1982), and Cairo (1987).[38]

Modern education in Islam

In general, minority religious groups often have more education than a country's majority religious group, even more so when a large part of that minority are immigrants.[39] This trend applies to Islam: Muslims in North America and Europe have more formal years of formal education than Christians.[40] Furthermore, Christians have more formal years of education in many majority Muslim countries, such as in sub-Saharan Africa.[40] However, global averages of education are far lower for Muslims than Jews, Christians, Buddhists and people unaffiliated with a religion.[39] Globally, Muslims and Hindus tend to have the fewest years of schooling.[41] However, younger Muslims have made much larger gains in education than any of these other groups.[39]

There is a perception of a large gender gap in majority Islam countries, but this is not always the case.[42] In fact, the quality of female education is more closely related to economic factors than religious factors.[42] Although the gender gap in education is real, it has been continuing to shrink in recent years.[43] Women in all religious groups have made much larger educational gains comparatively in recent generations than men.[39]

Europe's treatment of education of Muslims has shifted in the last few decades, with many countries developing some sort of new legislation regarding instructing with a religious bias starting in the late twentieth century. However, regardless of these changes, some level of inequality in access to education is still prevalent. In England, there are only 5 state-funded Muslim schools; this is in contrast to 4,716 state-funded Christian schools.[44] However, there are around 100 private Muslim schools which can instruct on religious education independent of the National Curriculum. In France, on the other hand, there are only 2 private Muslim schools. There are 30 private Muslim schools in the Netherlands.[44] This is despite the fact that Muslims make up the second largest religious population in Europe, following Christianity, with majorities being held in both Turkey (99%) and Albania (70%).[44]

Pesantren are Islamic boarding schools found in Muslim countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines. These types of schools have received criticism for their tendency to focus more on religious subjects than secular school subjects, and in fact, pesantren taught primarily religious education until the late 1970s.[45] Due to this focus, some have even accused these schools as being breeding grounds for Islamic extremism and terrorism.[46] Others argue that pesantren teach secular subjects at the same level as any other school, steering students from extremism through education and opening the door for young Muslims of all backgrounds to go on to higher education and become involved in such fields as medicine, law, and the sciences.[45]

After 1975 reforms made by the Indonesian government, today many pesantren now include madrasas. Muslim poet and political activist Emha Ainun Najib studied at one of the more famous pesantren, called Gontor. Other notable alumni include Hidayat Nur Wahid, Hasyim Muzadi, and Abu Bakr Ba’asyir.[45]

Women in Islamic education

While formal studies in madrasas were open only to men, women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas (diplomas) in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation. Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[3]

One of the largest roles that women played in education in Islam is that of muhaddithas. Muhaddithas are women who recount the stories, teachings, actions, and words of Muhammad adding to the isnad by studying and recording hadiths.[47] In order for a man or woman to produce hadiths, they must first hold an ijazah, or a form of permission, often granted by a teacher from private studies and not from a madrasa, allowing a muhaddith/muhadditha permission to transmit specific texts. Some of the most influential Muhaddithas are Zaynab bint al-Kamal who was known for her extensive collection of hadiths, A'isha bint Abu Bakr was Muhammad's third wife and she studied hadith from the early age of four.[47] A'isha was well known and respected for her line of teachers and ijazahs allowing her to present information from the Sahih collections of al-Bukhari, the Sira of Ibn Hashim, and parts of the Dhamm al-Kalam from al-Hawari.[47] Rabi'a Khatun, sister of the Ayyubid sultan Salah al-Din paid endowments to support the construction of a madrasa in Damascus, despite the facts that women were often not appointed teaching positions at the madrasas.[47] Because of Rabi'a Khatun's contributions to Damascus, scholarly traffic in the region increased greatly and involvement of female scholars boomed. As a result, female participation in hadith dissemination also grew.[47]

Among the areas in which individual's idiosyncratic views have been adopted and codified as veritable Islamic teaching throughout history include topics that relate to women's place in Islamic education. In some places, Muslim women have much more restricted access to education, despite the fact that this is not a mentioned doctrine in either the Quran or the Hadith.[30]

See also

- Sociology of education

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Islamic studies

- List of contemporary Muslim scholars of Islam

- Islamic literature

- Islamic advice literature

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Jonathan Berkey (2004). "Education". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- ^ a b c d e Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 217. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Islam - History of Islamic Education, Aims and Objectives of Islamic Education". education.stateuniversity.

- ^ Hilgendorf, Eric (April 2003). "Islamic Education: History and Tendency". Peabody Journal of Education. 78 (2): 63–75. doi:10.1207/S15327930PJE7802_04. ISSN 0161-956X. S2CID 129458856.

- ^ a b Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 210. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- ^ Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e Brentjes, Sonja (2018). Teaching and Learning the Sciences in Islamicate Societies. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publisher. pp. 33–34. ISBN 9782503574455.

- ^ Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e Pormann, Peter E. (2007). Medieval Islamic Medicine. Georgetown University Press. pp. 43–51. ISBN 9781589011618.

- ^ a b Sanagustin, F. (2012). "Mizād̲j̲". Brill. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Syros, Vasileios (2013). "Galenic Medicine and Social Stability in Early Modern Florence and the Islamic Empires". Journal of Early Modern History. 17 (2): 166–168. doi:10.1163/15700658-12342361 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ Kerschberg, Benjamin S. (2005). Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History. Berkshire Publishing Group. pp. 951–952. ISBN 0974309109.

- ^ The Guinness Book Of Records, Published 1998, ISBN 0-553-57895-2, p. 242

- ^ Verger, Jacques: "Patterns", in: Ridder-Symoens, Hilde de (ed.): A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-54113-8, pp. 35–76 (35)

- ^ Esposito, John (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-1951-2559-7.

- ^ Joseph, S, and Najmabadi, A. Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures: Economics, education, mobility, and space. Brill, 2003, p. 314.

- ^ Swartley, Keith. Encountering the World of Islam. Authentic, 2005, p. 74.

- ^ A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 2003, 35

- ^ Petersen, Andrew: Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, 1996, ISBN 978-0-415-06084-4, p. 87 (entry "Fez"):

The Quaraouiyine Mosque, founded in 859, is the most famous mosque of Morocco and attracted continuous investment by Muslim rulers.

- ^ Lulat, Y. G.-M.: A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis Studies in Higher Education, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3, p. 70:

As for the nature of its curriculum, it was typical of other major madrasahs such as al-Azhar and Al Quaraouiyine, though many of the texts used at the institution came from Muslim Spain...Al Quaraouiyine began its life as a small mosque constructed in 859 C.E. by means of an endowment bequeathed by a wealthy woman of much piety, Fatima bint Muhammed al-Fahri.

- ^ a b Belhachmi, Zakia: "Gender, Education, and Feminist Knowledge in al-Maghrib (North Africa) – 1950–70", Journal of Middle Eastern and North African Intellectual and Cultural Studies, Vol. 2–3, 2003, pp. 55–82 (65):

The Adjustments of Original Institutions of the Higher Learning: the Madrasah. Significantly, the institutional adjustments of the madrasahs affected both the structure and the content of these institutions. In terms of structure, the adjustments were twofold: the reorganization of the available original madaris and the creation of new institutions. This resulted in two different types of Islamic teaching institutions in al-Maghrib. The first type was derived from the fusion of old madaris with new universities. For example, Morocco transformed Al-Qarawiyin (859 A.D.) into a university under the supervision of the ministry of education in 1963.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin: Encyclopedia of African History, Vol. 2, Fitzroy Dearborn, 2005, ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6, p. 1025:

They consider institutions like al-Qarawiyyin to be higher education colleges of Islamic law where other subjects were only of secondary importance.Higher education has always been an integral part of Morocco, going back to the ninth century when the Karaouine Mosque was established. The madrasa, known today as Al Qayrawaniyan University, became part of the state university system in 1947.

- ^ Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R.: "Madrasa", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edition, Brill, 2010:

Madrasa, in modern usage, the name of an institution of learning where the Islamic sciences are taught, i.e. a college for higher studies, as opposed to an elementary school of traditional type (kuttab); in medieval usage, essentially a college of law in which the other Islamic sciences, including literary and philosophical ones, were ancillary subjects only.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (ed.): Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, A–K, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7, p. 457 (entry "madrasa"):

A madrasa is a college of Islamic law. The madrasa was an educational institution in which Islamic law (fiqh) was taught according to one or more Sunni rites: Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, or Hanbali. It was supported by an endowment or charitable trust (waqf) that provided for at least one chair for one professor of law, income for other faculty or staff, scholarships for students, and funds for the maintenance of the building. Madrasas contained lodgings for the professor and some of his students. Subjects other than law were frequently taught in madrasas, and even Sufi seances were held in them, but there could be no madrasa without law as technically the major subject.

- ^ Makdisi, George: "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages", Studia Islamica, No. 32 (1970), pp. 255–264 (255f.):

In studying an institution which is foreign and remote in point of time, as is the case of the medieval madrasa, one runs the double risk of attributing to it characteristics borrowed from one's own institutions and one's own times. Thus gratuitous transfers may be made from one culture to the other, and the time factor may be ignored or dismissed as being without significance. One cannot therefore be too careful in attempting a comparative study of these two institutions: the madrasa and the university. But in spite of the pitfalls inherent in such a study, albeit sketchy, the results which may be obtained are well worth the risks involved. In any case, one cannot avoid making comparisons when certain unwarranted statements have already been made and seem to be currently accepted without question. The most unwarranted of these statements is the one which makes of the "madrasa" a "university".

- ^ a b Lulat, Y. G.-M.: A History Of African Higher Education From Antiquity To The Present: A Critical Synthesis, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, ISBN 978-0-313-32061-3, pp. 154–157

- ^ Park, Thomas K.; Boum, Aomar: Historical Dictionary of Morocco, 2nd ed., Scarecrow Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-8108-5341-6, p. 348

al-qarawiyin is the oldest university in Morocco. It was founded as a mosque in Fès in the middle of the ninth century. It has been a destination for students and scholars of Islamic sciences and Arabic studies throughout the history of Morocco. There were also other religious schools like the madras of ibn yusuf and other schools in the sus. This system of basic education called al-ta'lim al-aSil was funded by the sultans of Morocco and many famous traditional families. After independence, al-qarawiyin maintained its reputation, but it seemed important to transform it into a university that would prepare graduates for a modern country while maintaining an emphasis on Islamic studies. Hence, al-qarawiyin university was founded in February 1963 and, while the dean's residence was kept in Fès, the new university initially had four colleges located in major regions of the country known for their religious influences and madrasas. These colleges were kuliyat al-shari's in Fès, kuliyat uSul al-din in Tétouan, kuliyat al-lugha al-'arabiya in Marrakech (all founded in 1963), and kuliyat al-shari'a in Ait Melloul near Agadir, which was founded in 1979.

- ^ Halm, Heinz. The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning. London: The Institute of Ismaili Studies and I.B. Tauris. 1997.

- ^ Donald Malcolm Reid (2009). "Al-Azhar". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5.

- ^ a b Alkanderi, Latefah. "Exploring Education in Islam: Al-Ghazali's Model of the Master-Pupil Relationship Applied to Educational Relationships within the Islamic Family". Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School.

- ^ a b Hafiz Khamis Al-Hafiz, Muhammad. "The Philosophy and Objectives of Education in Islam" (PDF). International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM).

- ^ Ibrahim, Faroukh Ibrahim; Haryanto, Budi (2020-12-31). "Islamic Education Concept Syed Muhammad Naquib Al Attas". Academia Open. 3. doi:10.21070/acopen.3.2020.2092. ISSN 2714-7444. S2CID 238959409.

- ^ Hafiz Khamis Al-Hafiz, Muhamad (2010). "The Philosophy and Objectives of Education in Islam" (PDF). International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM).

- ^ Mutahhari, Murtaza (2011-08-22). Training and Education in Islam. Islamic College for Advanced Studie. p. 5. ISBN 978-1904063445.

- ^ Fathi, Malkawi; Abdul-Fattah, Hussein (1990). The Education Conference Book: Planning, Implementation Recommendations and Abstracts of Presented Papers. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT). ISBN 978-1565644892.

- ^ Edwards, Viv; Corson, David (1997). Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Kluwer Academic publication. ISBN 978-1565644892.

- ^ Koehler, Benedikt (2011). Female Entrepreneurship in Early Islam. Economic Affairs. pp. 93–95.

- ^ "Education". oxfordislamicstudies.

- ^ a b c d "Key findings on how world religions differ by education". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ a b "Muslim educational attainment around the world". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "Religion and Education Around the World". Pew Research Center. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- ^ a b "Economics may limit Muslim women's education more than religion". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ "The Muslim gender gap in education is shrinking". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- ^ a b c Gent, Bill (January 2011). "Islam in education in European countries: pedagogical concepts and empirical findings, edited by Aurora Alvarez Veinguer, Gunther Dietz, Dan‐Paul Jozsa and Thorsten Knauth". British Journal of Religious Education. 33 (1): 99–101. doi:10.1080/01416200.2011.527467. ISSN 0141-6200. S2CID 144796042.

- ^ a b c Woodward, Mark (2010). "Muslim Education, Celebrating Islam and Having Fun As Counter-Radicalization Strategies in Indonesia" (PDF). Terrorism ::Research Initiative 4. 4 (4): 28–50. JSTOR 26298470 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Woodward, Mark; Yahya, Mariani; Rohmaniyah, Inayah; Coleman, Diana Murtaugh; Lundry, Chris; Amin, Ali (2013-12-28). "The Islamic Defenders Front: Demonization, Violence and the State in Indonesia". Contemporary Islam. 8 (2): 153–171. doi:10.1007/s11562-013-0288-1. ISSN 1872-0218. S2CID 144750224.

- ^ a b c d e Sayeed, Asma (2013). Women and the Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–173. ISBN 978-1107031586.