George Washington University Law School

| George Washington University Law School | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parent school | George Washington University |

| Established | 1865[1] |

| School type | Private |

| Parent endowment | $2.41 billion |

| Location | |

| Enrollment | 1,646[2] |

| Faculty | 371[2] |

| USNWR ranking | 25th (2023)[3] |

| Bar pass rate | 88.02%[2] |

| Website | www |

| |

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital.[5][6] GW Law offers the largest range of courses in the US, with 275 elective courses in business and finance law, environmental law, government procurement law, intellectual property law, international comparative law, litigation and dispute resolution, and national security and U.S. foreign relations law.[7][8] Admissions are highly selective as the law school receives thousands of applications.[9] In 2020, the acceptance rate was 21%.[10]

GW Law has an alumni network that includes notable people within the fields of law and government, including the former U.S. Attorney General, the former U.S. Secretary of the Interior, foreign heads of state, judges of the International Court of Justice, ministers of foreign affairs, a Director-General of the World Intellectual Property Organization, a Director of the CIA, members of U.S. Congress, U.S. State Governors, four Directors of the FBI, and numerous Federal judges. The law school publishes nine student-run journals and hosts highly ranked skills competitions, such as the Van Vleck Constitutional Law Moot Court Competition.[11] In 2020 GW was ranked as the 11th best moot court program in the country and regularly hosts a U.S. Supreme Court justice on its three-judge panel.[12]

The 2023 U.S. News & World Report ranks GW Law as the 25th top law school in the United States.[13] The National Law Journal ranked GW Law 21st for law schools that sent the highest percentage of new graduates to NLJ 250 law firms, the largest and most prominent law practices in the U.S.[14]

History

The George Washington University Law School was founded in the 1820s but closed in 1826 due to low enrollment.[5] The law school's first two professors were William Cranch, chief justice of the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia and second reporter of the U.S. Supreme Court, and William Thomas Carroll, a descendant of Charles Carroll the Settler and clerk of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1827 until his death in 1863.[15] The law school was reestablished in 1865 and was the first law school in the District of Columbia.[5]

Law classes resumed in 1865 in the Old Trinity Episcopal Church, and the school graduated its first class of 60 students in 1867.[1] The Master of Laws degree program was adopted by the school in 1897.[1] In 1900, the school was one of the founding members of the Association of American Law Schools.[1] In 1954, it merged with National University School of Law of Washington.[1] The law school operated under the name National Law Center for the 37 years from 1959 to 1996, when it was renamed George Washington University Law School.[16]

Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas, William Strong, David J. Brewer, Willis Van Devanter, and John Marshall Harlan were among those who served on its faculty.[17][18] Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Antonin Scalia, Justice Elena Kagan, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and Justice Samuel Alito presided over its moot court in 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014, and 2016.[19][20][21]

GW Law has the oldest intellectual property program in the country, with alumni having written patents for some of the greatest technological achievements of the past 130 years—including the Wright brothers' flying machine, patented on May 22, 1906.[22]

The school was accredited by the American Bar Association in 1923[23] and was a charter member of the Association of American Law Schools.[24]

- National University School of Law

The National University School of Law was merged into the George Washington University School of Law in 1954.[25] The school was founded in 1869.[26] Many alumni served in prominent political and legal positions throughout the school's history.

Academics

Curriculum

J.D. students are required to take courses on civil procedure, criminal law, constitutional law, contracts, introduction to advocacy, legal research and writing, professional responsibility and ethics, property, and torts.[27]

GW Law offers more than 275 elective courses each year.[28] The school boasts particularly robust offerings in business and finance law, environmental law, government procurement law, intellectual property law, international comparative law, litigation and dispute resolution, and national security and U.S. foreign relations law.[7]

GW Law also offers numerous summer programs, including a joint program with the University of Oxford for the study of international human rights law at New College, Oxford each July.[29]

Degrees offered

In addition to the Juris Doctor degree, GW Law offers the following joint degrees:[30]

- J.D./M.B.A. with the School of Business

- J.D./Master of Public Administration with the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration

- J.D./Master of Public Policy with the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration

- J.D./M.A. with the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences in History (with a concentration in U.S. Legal History), in Women's Studies, or in Public Policy (with a concentration in Women's Studies)

- J.D./M.A. with the Elliott School of International Affairs

- J.D./Master of Public Health with the Milken Institute School of Public Health

- J.D./Public Health Certificate with the Milken Institute School of Public Health

The school also offers Master of Laws (LL.M.) in Environmental Law, Business and Finance Law, International Environmental Law, Government Procurement and Environmental Law, Intellectual Property Law, International and Comparative Law, Government Procurement Law, Litigation and Dispute Resolution, and National Security and U.S. Foreign Relations Law.[31] The Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) is offered to a very limited number of candidates.[32]

Student recognition

Instead of supplying students with individual class rankings, GW Law recognizes academic performance with two scholar designations.[33] The top 1–15% of the class is designated George Washington Scholars while the top 16–35% of the class is designated Thurgood Marshall Scholars.[33]

Publications

GW Law publishes nine journals:[34]

- The George Washington Law Review

- The George Washington International Law Review

- The George Washington Business & Finance Law Review

- The Federal Circuit Bar Journal

- The American Intellectual Property Law Association Quarterly Journal

- The Public Contract Law Journal

- The Federal Communications Law Journal

- The Journal of Energy and Environmental Law

- International Law in Domestic Courts Journal

Student life

With more than 1,600 J.D. students enrolled in the 2013–2014 academic year, GW Law had the fifth largest J.D. enrollment of all ABA-accredited law schools.[35]

In the 2013–2014 academic year, 25.2% of GW Law students were minorities and 46.2% were female.[36]

Students enrolled in the J.D. program come from 206 colleges and 11 countries.[37] The law school also enrolls students from approximately 45 countries each year in its Master of Laws and Doctor of Juridical Science degree programs.[38]

GW Law students can participate in 60 student groups.[39]

Campus

GW Law is located in the heart of Washington's Foggy Bottom neighborhood, across the street from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund headquarters, and a few blocks away from the State Department and the White House.[40]

The Jacob Burns Law Library holds a collection of more than 700,000 volumes.[41]

In 2000, the law school began a major building and renovation plan. The school has expanded into buildings on the east side of the University Yard.

The law school currently occupies nine buildings on the main campus of The George Washington University. The law school's main complex comprises five buildings anchored by Stockton Hall (1924) located on the University Yard, the central open space of GW's urban campus. Renovated extensively between 2001 and 2003, these buildings adjoin one another, have internal passageways, and function as one consolidated complex. Three townhouses directly across from the main complex house the Community Legal Clinics, Student Bar Association, and student journal offices.

Admissions

For the class entering in the fall of 2019, 2,488 out of 8,019 J.D. applicants (31%) were offered admission, with 489 matriculating. The 25th and 75th LSAT percentiles for the 2019 full-time entering class were 160 and 167, respectively, with a median of 166 (93rd percentile[42]).[43] The 25th and 75th undergraduate GPA percentiles were 3.40 and 3.84, respectively, with a median of 3.74.[44] In the 2018–19 academic year, GW Law had 1,525 J.D. students, of which 25% were minorities and 51% were female.[44]

In order to apply for the J.D. program, students must have taken the LSAT within the past five years and must submit a personal statement and at least one letter of recommendation.[45] The GRE is also accepted instead of the LSAT. An applicant with scores for both the GRE and LSAT will have its LSAT score reviewed. Applications are considered on a rolling basis starting in October and must be submitted by March 1.[45]

U.S. Supreme Court clerkships

Since 2005, GW Law has had seven alumni serve as judicial clerks at the U.S. Supreme Court, one of the most distinguished appointments a law school graduate can obtain. This record gives GW Law a ranking of 14th among all law schools nationwide (out of 204 ABA-approved law schools) for supplying such law clerks for the period between 2005 and 2017.

GW Law has placed 27 clerks at the U.S. Supreme Court in its history, including in the 1930s Francis R. Kirkham, later partner at Pillsbury, Madison & Sutro in San Francisco and then general counsel to Standard Oil of California, and Reynolds Robertson, who worked for Cravath, deGersdorff, Swaine & Wood in New York City, both co-authors of a seminal work on the Court's jurisdiction.[46][47][48]

Post-graduation employment

According to GW Law's official 2019 ABA-required disclosures, 73.6% of the Class of 2019 obtained full-time, long-term, bar passage-required, non-school funded employment ten months after graduation.[49]

GW Law's Law School Transparency under-employment score is 12.1%, indicating the percentage of the Class of 2019 unemployed, pursuing an additional degree, or working in a non-professional, short-term, or part-time job ten months after graduation.[50] 0.6% of graduates were in school-funded jobs. 89.5% of the Class of 2019 was employed in some capacity, 1.4% were pursuing a graduate degree, and 6.8% were unemployed and seeking employment.[49]

The main employment destinations for 2019 GW Law graduates were Washington, D.C., New York City, and Virginia.[49]

Costs

The total cost of full-time attendance (indicating the cost of tuition, fees, and living expenses) at GW Law for the 2018-2019 academic year was $88,340.[51] GW Law's tuition and fees on average increased by 4.1% annually over the past five years.[52]

The Law School Transparency estimated debt-financed cost of attendance for three years is $328,263.[52] The average indebtedness of the 76% of 2013 GW Law graduates who took out loans was $123,693.[53]

Rankings

GW Law is ranked #25 in the 2023 Law School Rankings of U.S. News & World Report. GW Law ranks #5 for its international law program, #5 for intellectual property law, #2 for part-time law, and #10 for environmental law.[54]

The National Law Journal ranked GW Law 21st in its 2014 Go-To Law Schools list, a ranking of which law schools sent the highest percentage of new graduates to NLJ 250 law firms.[55]

According to Brian Leiter's law school rankings, GW Law ranked 17th in the nation for Supreme Court clerkship placement between 2003 and 2013,[56] 19th in terms of student numerical quality,[57] and 16th for law faculties with the most "scholarly impact" as measured by numbers of citations.[58]

Notable people

- Notable Alumni of the GW Law School

-

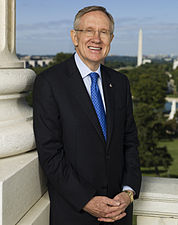

Former U.S. Senator Harry Reid, former Senate Majority Leader

-

Belva Ann Lockwood, first woman to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court

-

Hsu Mo, founding judge of the International Court of Justice

-

Former U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright, founder of the Fulbright Program

-

J. Edgar Hoover, 1st director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

-

Patricia Roberts Harris, first African American woman to serve in the U.S. Cabinet

Notable faculty

Notable faculty members include:

- Clarence Thomas[59]

- John Banzhaf

- Jerome A. Barron

- Paul Schiff Berman

- Thomas Buergenthal

- Steve Charnovitz

- Mary Cheh

- Donald C. Clarke

- Lawrence Cunningham

- William Kovacic

- Alan Morrison

- Ralph Oman

- Richard J. Pierce

- Randall Ray Rader

- Charles Henry Robb

- Jeffrey Rosen

- Catherine J. Ross

- Lisa M. Schenck

- Jonathan Turley

- Daniel Solove

-

GW Law professor Clarence Thomas, Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

-

FAMRI Dr. William Cahan Distinguished Professor John F. Banzhaf III; legal activist; devised the Banzhaf power index

-

Former Elyce Zenoff Research Professor of Law (1979) Mary Cheh in 2010; elected D.C. councilwoman

-

GW Law professor Thomas Buergenthal, former judge of the International Court of Justice

-

GW Law professor and legal writer Steve Charnovitz in 2019

-

GW Law professor Jeffrey Rosen, National Constitution Center chair and CEO; constitutional law journalist and commentator

-

GW Law professor and constitutional lawyer, Jonathan Turley

References

- ^ a b c d e "History". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c George Washington University – 2016 Standard 509 Information Report (PDF) (Report).

- ^ "George Washington University". U.S. News & World Report – Best Law Schools. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "2020 Law School Rankings - Acceptance Rate (Low to High)".

- ^ a b c "Showing Our Strengths: The History and Future of GW Law". GW Law. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "USNews – Best Law Schools".

- ^ a b "Academic Focus Areas". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Why GW Law?". www.law.gwu.edu. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ "JD Entering Class Profile". www.law.gwu.edu. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ https://www.law.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs2351/f/downloads/2021-ABA-Standard-509-Report-2.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Internal Competitions". www.law.gwu.edu. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ "Van Vleck Constitutional Law Moot Court Competition | GW Moot Court Board". Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ "George Washington University". 2023 Best Law Schools - US News Rankings. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "Explore the Data Behind the Go-To Law Schools". February 24, 2014.

- ^ "A Legal Miscellanea". Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "GW Law: 150 Years of Making History, pp.12–13". Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ "Probing the Law School's Past: 1821–1962". The GW and Foggy Bottom Historical Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Kwiecinski, Matthew. "Supreme Court justice joins faculty". GW Hatchet. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Butler, Brandon. "Roberts judges moot court competition". The GW Hatchet. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Moot Court Competition". C-SPAN. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Kagan rules in annual moot court competition". The GW Hatchet. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Showing Our Strengths". Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "Alphabetical School List". American Bar Association. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Member and Fee-Paid Schools". The Association of American Law Schools. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Stevens, Robert Bocking (2001). Law School: Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s – Robert Bocking Stevens – Google Books. ISBN 9781584771999. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ "National University - GW Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Required J.D. Curriculum". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Curriculum Overview". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "GW-Oxford Summer Program". GW Law. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ "Joint Degree Programs". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ "GW Law at a Glance". GW Law. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "S.J.D. Admissions". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ a b "Academic Recognition and Grade Representation Policy". GW Law. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Publications". GW Law. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ "Fall 2013 JD and Non-JD Enrollment". American Bar Association. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Section of Legal Education – ABA Required Disclosures". American Bar Association. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome New Students". GW Law. Retrieved August 19, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Admissions". GW Law. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Students Organizations". GW Law. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "DC & GW". GW Law. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Jacob Burns Law Library". GW Law. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "LSAT Score Percentiles". Manhattan Review. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ "George Washington University – 2019 Standard 509 Information Report" (PDF). December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "2019 Standard 509 Information Report" (PDF). American Bar Association. December 4, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "J.D. Admissions Requirements". GW Law. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Death: Francis R. Kirkham". Deseret News. October 27, 1996. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Swaine, Robert T. (1946). The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors, 1819–1947, Volume 1. Reprint 2006, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. xvii, n 279. ISBN 1584777133.

- ^ Robertson, Reynolds; Kirkham, Francis R; Wolfson, Richard F; Kurland, Philip B (1951). Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United States. Albany: Matthew Bender. ISBN 0598833137. OCLC 1884480. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Employment Summary for 2019 Graduates" (PDF). GW Law.

- ^ "George Washington University". www.lstreports.com.

- ^ "Cost of Attendance". GW Law. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "George Washington University Profile, Costs". Law School Transparency. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ "Which law school graduates have the most debt?". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "GW Law – US News & World Report".

- ^ "Explore the Data Behind the Go-To Law Schools". National Law Journal. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Supreme Court Clerkship Placement, 2003 Through 2013, 2013". Brian Leiter's Law School Rankings. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "2010 Ranking of Student Bodies By Numerical Quality". Brian Leiter's Law School Rankings. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Top 70 Law Faculties In Scholarly Impact, 2007–2011". Brian Leiter's Law School Rankings. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ GW Law School – Faculty: Clarence Thomas