High Noon

| High Noon | |

|---|---|

| File:High Noon poster.jpg 1952 theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Fred Zinnemann |

| Screenplay by | Carl Foreman |

| Story by | John W. Cunningham |

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer (uncredited) Carl Foreman (uncredited) |

| Starring | Gary Cooper Grace Kelly |

| Cinematography | Floyd Crosby, ASC |

| Edited by | Elmo Williams Harry W. Gerstad |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

Production company | Stanley Kramer Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $730,000 |

| Box office | $3.4 million (US in 1952)[1] $8,000,000[2] |

High Noon is a 1952 American Western film directed by Fred Zinnemann and starring Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly. The film tells in real time the story of a town marshal forced to face a gang of killers by himself. The screenplay was written by Carl Foreman.

In 1989, High Noon was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant," entering the registry during the latter's first year of existence.[3] The film is #27 on the American Film Institute's 2007 list of great films.

Plot

Will Kane (Gary Cooper), the longtime marshal of Hadleyville, New Mexico Territory, has just married pacifist Quaker Amy (Grace Kelly) and turned in his badge. He intends to become a storekeeper elsewhere. Suddenly, the town learns that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald)—a criminal Kane brought to justice—is due to arrive on the noon train.

Miller had been sentenced to hang but was pardoned on an unspecified legal technicality. In court, he had vowed to get revenge on Kane and anyone else who got in the way. Miller's three gang members (his younger brother Ben (Sheb Wooley), Jack Colby and Pierce) wait for him at the station.

Kane and his wife leave town, but fearing that the gang will hunt him down and be a danger to the townspeople, Kane turns back. He reclaims his badge and scours the town for help, even interrupting Sunday church services, with little success. His deputy, Harvey Pell (Lloyd Bridges), resigns because Kane did not recommend him as the new marshal.

Kane goes to warn Helen Ramírez (Katy Jurado), first Frank Miller’s lover, then Kane's, and now Harvey's. Aware of what Miller will do to her if he finds her, she quickly sells her business and prepares to leave town.

Amy gives her husband an ultimatum: she is leaving on the noon train, with or without him.

The worried townspeople encourage Kane to leave, hoping that would defuse the situation. Even Kane's good friends the Fullers are at odds about how to deal with the situation. Mildrid Fuller (Eve McVeagh) wants her husband (Harry Morgan) to speak with Kane when he comes to their home, but he makes her claim he is not home.

In the end, Kane faces the Miller Gang alone. Kane guns down two of the gang, though he himself is wounded in the process. Helen Ramirez and Amy both board the train (pulled by the famous locomotive, Sierra No. 3), but Amy gets off when she hears the sound of gunfire. Amy chooses her husband's life over her religious beliefs, shooting Pierce from behind. Frank then takes her hostage to force Kane into the open. However, Amy suddenly attacks Frank, giving Kane a clear shot, and Kane shoots Frank Miller dead. As the townspeople emerge, Kane contemptuously throws his marshal's star in the dirt and leaves town with his wife.

Cast

- Gary Cooper as Marshal Will Kane

- There was some controversy over the casting of Cooper as the lead: at 50, nearly 30 years older than co-star Kelly, he was considered too old for the role.[4]

- Thomas Mitchell as Mayor Jonas Henderson

- Lloyd Bridges as Deputy Sheriff Harvey Pell

- Katy Jurado as Helen Ramirez

- Grace Kelly as Amy (Fowler) Kane

- Otto Kruger as Judge Percy Mettrick

- Lon Chaney, Jr. as Martin Howe (as Lon Chaney)

- Harry Morgan as Sam Fuller (as Henry Morgan)

- Ian MacDonald as Frank Miller

- Eve McVeagh as Mildred Fuller

- Morgan Farley as Dr. Mahin, minister

- Harry Shannon as Cooper

- Lee Van Cleef as Jack Colby

- Robert J. Wilke as Pierce (as Robert Wilke)

- Sheb Wooley as Ben Miller

Production

According to the 2002 documentary Darkness at High Noon: The Carl Foreman Documents, written, produced, and directed by Lionel Chetwynd, Foreman's role in the creation and production of High Noon has over the years been unfairly downplayed in favor of Foreman's former partner and producer, Stanley Kramer.[5] The documentary was prompted by and based in part on a single-spaced 11-page letter that Foreman wrote to film critic Bosley Crowther in April 1952.[5] In the letter, Foreman asserts that the film began as a four-page plot outline about "aggression in a western background" and "telling a motion picture story in the exact time required for the events of the story itself" (a device used in High Noon).[5] An associate of Foreman pointed out similarities between Foreman's outline and the short story "The Tin Star" by John W. Cunningham, which led Foreman to purchase the rights to Cunningham's story and proceed with the original outline.[5] By the time the documentary aired, most of those immediately involved were dead, including Kramer, Foreman, Fred Zinnemann, and Gary Cooper. Kramer's widow rebuts Foreman's contentions; Victor Navasky, author of Naming Names and familiar with some of the circumstances surrounding High Noon because of interviews with Kramer's widow among others, said the documentary seemed "one-sided, and the problem is it makes a villain out of Stanley Kramer, when it was more complicated than that."[5]

The film's production and release also intersected with the second Red Scare and the Korean War. Writer, producer, and partner Carl Foreman was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) while he was writing the film. Foreman had not been in the Communist Party for almost ten years, but he declined to name names and was considered an "uncooperative witness" by the HUAC.[6] When Stanley Kramer found out some of this, he forced Foreman to sell his part of their company, and tried to get him kicked off the making of the picture. Fred Zinnemann, Gary Cooper, and Bruce Church intervened. There was also a problem with the Bank of America loan, as Foreman had not yet signed certain papers. Thus, Foreman remained on the production but moved to England before it was released nationally, as he knew he would never be allowed to work in America.[6]

Kramer claimed he had not stood up for Foreman partly because Foreman was threatening, dishonestly, to name Kramer as a Communist.[6] Foreman said that Kramer was afraid of what would happen to him and his career if Kramer did not cooperate with the Committee. Kramer wanted Foreman to name names and not plead his Fifth Amendment rights.[6] Foreman was eventually blacklisted by the Hollywood companies. There had also been pressure against Foreman by, among others, Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures (Kramer's brand new boss at the time), John Wayne of the MPA, and Hedda Hopper of the Los Angeles Times.[6] Cast and crew members were also affected. Howland Chamberlin was blacklisted while Floyd Crosby and Lloyd Bridges were "graylisted."[6]

Reception

Upon its release, the film was criticized by audiences, as it did not contain such expected Western archetypes as chases, violence, action, and picture postcard scenery. Rather, it presented emotional and moralistic dialogue throughout most of the film. Only in the last few minutes were there action scenes.[7]

In the Soviet Union the film was criticized as "a glorification of the individual."[6] The American Left appreciated the film for what they believed was an allegory of people (Hollywood people, in particular) who were afraid to stand up to HUAC. However, the film eventually gained the respect of people with conservative/anti-communist views. Ronald Reagan, a conservative and fervent anti-Communist, said he appreciated the film because the main character had a strong dedication to duty, law, and the well-being of the town despite the refusal of the townspeople to help. Dwight Eisenhower loved the film and frequently screened it in the White House, as did many other American presidents.[6] Bill Clinton cited High Noon as his favorite film and screened it a record 17 times at the White House.[8]

Actor John Wayne disliked the film because he felt it was an allegory for blacklisting, which he actively supported. In his Playboy interview from May 1971, Wayne stated he considered High Noon "the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life"[9] and went on to say he would never regret having helped blacklist liberal screenwriter Carl Foreman from Hollywood. Ironically, Gary Cooper himself had conservative political views and was a "friendly witness" before HUAC several years earlier, although he did not name names and later strongly opposed blacklisting.[10] Wayne accepted Cooper's Academy Award for the role as Cooper was unable to attend the presentation.

In 1959, Wayne teamed up with director Howard Hawks to make Rio Bravo as a conservative response. Hawks explained, "I made Rio Bravo because I didn't like High Noon. Neither did Duke. I didn't think a good town marshal was going to run around town like a chicken with his head cut off asking everyone to help. And who saves him? His Quaker wife. That isn't my idea of a good Western." [11]

Irritated by Hawks's criticisms, director Fred Zinnemann responded, "I admire Hawks very much. I only wish he'd leave my films alone!" [12] Zinnemann later said in a 1973 interview, "I'm told that Howard Hawks has said on various occasions that he made Rio Bravo as a kind of answer to High Noon, because he didn't believe that a good sheriff would go running around town asking for other people's help to do his job. I'm rather surprised at this kind of thinking. Sheriffs are people and no two people are alike. The story of High Noon takes place in the Old West but it is really a story about a man's conflict of conscience. In this sense it is a cousin to A Man for All Seasons. In any event, respect for the Western Hero has not been diminished by High Noon." [13]

Accolades

The movie won Academy Awards for:

- Best Actor in a Leading Role - Gary Cooper

- Best Film Editing - Elmo Williams and Harry W. Gerstad [14]

- Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture - Dimitri Tiomkin

- Best Music, Song - Dimitri Tiomkin and Ned Washington for "Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin'", sung by Tex Ritter.

The film was nominated for Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Writing, Screenplay.[15] It lost Best Picture to Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth.

Entertainment Weekly ranked Will Kane on their list of The 20 All Time Coolest Heroes in Pop Culture.[16]

Producer Carl Foreman would later be blacklisted from Hollywood. Ironically, despite disliking the film, it was John Wayne who picked up the absent Gary Cooper's Academy Award.

Mexican actress Katy Jurado won the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress for her role of Helen Ramirez, becoming the first Mexican actress to receive the award.

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies #33

- 2001 AFI's 100 Years…100 Thrills #20

- 2003 AFI's 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains:

- Will Kane, hero #5

- 2004 AFI's 100 Years…100 Songs:

- 2005 AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores #10

- 2006 AFI's 100 Years…100 Cheers #27

- 2007 AFI's 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #27

- 2008 AFI's 10 Top 10 #2 Western film

Cultural influence

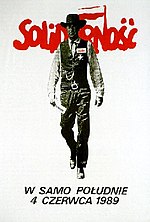

In 1989, 22-year-old Polish graphic designer Tomasz Sarnecki transformed Marian Stachurski's 1959 Polish variant of the High Noon poster into a Solidarity election poster for the first partially free elections in communist Poland. The poster, which was displayed all over Poland, shows Cooper armed with a folded ballot saying "Wybory" (i.e. election) in his right hand while the Solidarity logo is pinned to his vest above the sheriff's badge. The message at the bottom of the poster reads: "W samo południe: 4 czerwca 1989," which translates to "High Noon: 4 June 1989."

In 2004 former Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa wrote:[17]

Under the headline "At High Noon" runs the red Solidarity banner and the date—June 4, 1989—of the poll. It was a simple but effective gimmick that, at the time, was misunderstood by the Communists. They, in fact, tried to ridicule the freedom movement in Poland as an invention of the "Wild" West, especially the U.S. But the poster had the opposite impact: Cowboys in Western clothes had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom, both physical and spiritual. Solidarity trounced the Communists in that election, paving the way for a democratic government in Poland. It is always so touching when people bring this poster up to me to autograph it. They have cherished it for so many years and it has become the emblem of the battle that we all fought together.

According to an English professor at Yeshiva University,[9] High Noon is the film most requested for viewing by U.S. presidents. It has been cited as the favorite film of Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower [18] and Bill Clinton.[18][19]

The conflict of the role of the Western hero is ironically portrayed in the film Die Hard. The villain confuses John Wayne as the hero walking off into the sunset with Grace Kelly, only to be corrected by the protagonist.[20]

High Noon is the favourite film of DCI Gene Hunt of Life on Mars and Ashes to Ashes. Hunt makes periodic references to the film throughout the two series' five seasons.

Remakes and sequel

- In 1966, Four Star Television produced a High Noon television pilot. The 30-minute pilot was called "The Clock Strikes Noon Again" and was set 20 years after the original movie. Peter Fonda played Will Kane Jr., who goes to Hadleyville after Frank Miller's son kills his father (the Gary Cooper character). His mother (the Grace Kelly character) dies shortly after from grief. In Hadleyville, Will Kane Jr. meets Helen Ramirez, played by Katy Jurado (who had played the same character in the original movie). Helen returned to town and was now running a hotel/restaurant. The script was written by James Warner Bellah. No series came from this unsold TV pilot.[21]

- A made-for-TV sequel, High Noon, Part II: The Return of Will Kane (produced in 1980, 28 years after the original movie was released), featured Lee Majors in the Cooper role. CBS ran this in a two-hour time slot on November 15, 1980.

- The 1980 science fiction film Outland borrowed from the story of High Noon for its plot. The movie starred Sean Connery.

- In 2000, High Noon was entirely reworked for the cable channel TBS with Tom Skerritt in the lead role. This remake is available on DVD.

Other appearances

- In 2002, The Simpsons 13th Season Finale "Poppa's Got a Brand New Badge" draws inspiration from both High Noon and The Sopranos when Homer, in charge of Spring Shield Security, has to face by himself the revenge of Fat Tony, whose operations Homer had disrupted.

- Gary Cooper has a cameo as his "High Noon" character Will Kane in the 1959 Bob Hope film Alias Jesse James. After shooting a bad guy, Will, wearing his "High Noon" tin star, said his only line in the film -- "Yup."

References

- ^ 'Variety Film Grosses of 1952', Film Data of 1952 accessed 11 May 1952

- ^ "Box Office Information for High Noon" The Numbers Retrieved: April 12, 2012

- ^ "NATIONAL FILM REGISTRY TITLES of the U.S. LIBRARY of CONGRESS". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Behind High Noon, hosted by Maria Cooper, 2002.

- ^ a b c d e Weinraub, Bernard (April 18, 2002). "'High Noon,' High Dudgeon". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Byman, Jeremy (2004). Showdown at High Noon: Witch-hunts, Critics, and the End of the Western. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4998-4.

- ^ The Making of High Noon, hosted by Leonard Maltin, 1992. Available on the Region 1 DVD from Artisan Entertainment.

- ^ Review © 2004 Branislav L. Slantchev

- ^ a b Manfred Weidhorn. "High Noon." Bright Lights Film Journal. February 2005. Accessed 12 February 2008.

- ^ Meyer, Jeffrey Gary Cooper: American Hero (1998)[page needed]

- ^ Michael Munn (2005). John Wayne: The Man Behind the Myth. Penguin. p. 148. ISBN 0-451-21414-5.

- ^ Fred Zinnemann: interviews - Fred Zinnemann, Gabriel Miller - Google Books

- ^ Gabriel Miller, ed. (2005). Fred Zinnemann: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 44. ISBN 1-57806-698-0.

- ^ Elmo Williams has said that Gerstad's editing was nominal and he apparently protested Gerstad's inclusion on the Academy Award at the time. See Williams, Elmo (2006), Elmo Williams: A Hollywood Memoir (McFarland), p. 86. ISBN 0-7864-2621-7.

- ^ "High Noon Award Wins and Nominations". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly's 20 All Time Coolest Heroes in Pop Culture". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ Lech Walesa. "In Solidarity." The Wall Street Journal. 11 June 2004. Accessed 15 March 2007.

- ^ a b DVD documentary Inside High Noon, John Mulholland.

- ^ Clinton, Bill (June 22, 2004). My Life. Knopf. p. 21.

- ^ Die Hard (1988) - Memorable quotes

- ^ IMDb: Katy Jurado (The Clock Strikes Noon Again)

External links

- High Noon at IMDb

- High Noon at the TCM Movie Database

- High Noon at AllMovie

- High Noon at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1952 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 1950s Western films

- Best Song Academy Award winners

- Black-and-white films

- Films based on short fiction

- Films directed by Fred Zinnemann

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award winning performance

- Films set in Kansas

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films set within one day

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- Tex Ritter songs

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films

- American Western films