Leszek Kołakowski

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Leszek Kołakowski | |

|---|---|

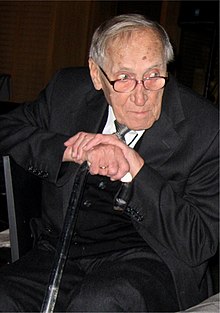

Kołakowski in 1971 | |

| Born | 23 October 1927 |

| Died | 17 July 2009 (aged 81) Oxford, England |

| Education | Łódź University University of Warsaw (PhD, 1953) |

| Notable work | Main Currents of Marxism (1976) |

| Awards | Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (1977) MacArthur Fellowship (1983) Erasmus Prize (1983) Kluge Prize (2003) Jerusalem Prize (2007) |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Warsaw |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Humanist interpretation of Marx Criticism of Marxism |

Leszek Kołakowski (/ˌkɒləˈkɒfski/; Polish: [ˈlɛʂɛk kɔwaˈkɔfskʲi]; 23 October 1927 – 17 July 2009) was a Polish philosopher and historian of ideas. He is best known for his critical analyses of Marxist thought, especially his three-volume history, Main Currents of Marxism (1976). In his later work, Kołakowski increasingly focused on religious questions. In his 1986 Jefferson Lecture, he asserted that "[w]e learn history not in order to know how to behave or how to succeed, but to know who we are".[1]

Due to his criticism of Marxism and of the Communist state system, Kołakowski was effectively exiled from Poland in 1968. He spent most of the remainder of his career at All Souls College, Oxford. Despite being in exile, Kołakowski was a major inspiration for the Solidarity movement that flourished in Poland in the 1980s[2] and helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet Union, leading to his being described by Bronislaw Geremek as the "awakener of human hopes".[3][full citation needed][4] He was awarded both the MacArthur Fellowship and Erasmus Prize in 1983, the 2003 Kluge Prize, and the 2007 Jerusalem Prize.

Biography

Kołakowski was born in Radom, Poland. He could not obtain formal schooling during the German occupation of Poland (1939–1945) in World War II, but he read books and took occasional private lessons, passing his school-leaving examinations as an external student in the underground school system. After the war, he studied philosophy at both University of Lodz and University of Warsaw, the latter of which he completed a doctorate at in 1953, focusing on Spinoza from a Marxist viewpoint.[5] He served as a professor and chair of Warsaw University's department of History of Philosophy from 1959 to 1968.

In his youth, Kołakowski became a communist. He signed a denunciation against Władysław Tatarkiewicz.[6] From 1947 to 1966, he was a member of the Polish United Workers' Party. His intellectual promise earned him a trip to Moscow in 1950.[7] He broke with Stalinism, becoming a revisionist Marxist advocating a humanist interpretation of Karl Marx. One year after the 1956 Polish October, Kołakowski published a four-part critique of Soviet Marxist dogmas, including historical determinism, in the Polish periodical Nowa Kultura.[8] His public lecture at Warsaw University on the tenth anniversary of Polish October led to his expulsion from the Polish United Workers' Party. In the course of the 1968 Polish political crisis, he lost his job at Warsaw University and was prevented from obtaining any other academic post.[9]

He came to the conclusion that the totalitarian cruelty of Stalinism was not an aberration but a logical end-product of Marxism, whose genealogy he examined in his monumental Main Currents of Marxism, his major work, published in 1976 to 1978.[10]

Kołakowski became increasingly fascinated by the contribution that theological assumptions make to Western culture and, in particular, modern thought. For example, he began his Main Currents of Marxism with an analysis of the contribution that various forms of ancient and medieval Platonism made, centuries later, to the Hegelian view of history. In the work, he criticized the laws of dialectical materialism for being fundamentally flawed and found some of them being "truisms with no specific Marxist content", others "philosophical dogmas that cannot be proved by scientific means" but others being just "nonsense".[11]

Kołakowski defended the role which freedom of will plays in the human quest for the transcendent. His Law of the Infinite Cornucopia asserted a doctrine of status quaestionis: for any given doctrine that one wants to believe, there is never a shortage of arguments by which one can support it.[12] Nevertheless, although human fallibility implies that we ought to treat claims to infallibility with scepticism, our pursuit of the higher (such as truth and goodness) is ennobling.

In 1968, Kołakowski became a visiting professor in the department of philosophy at McGill University in Montreal and in 1969 he moved to the University of California, Berkeley. In 1970, he became a senior research fellow at All Souls College, Oxford. He remained mostly at Oxford, but he spent part of 1974 at Yale University, and from 1981 to 1994, he was a part-time professor at the Committee on Social Thought and in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Chicago.

Although the Polish Communist authorities officially banned his works in Poland, underground copies of them influenced the opinions of the Polish intellectual opposition.[13] His 1971 essay Theses on Hope and Hopelessness (full title: In Stalin's Countries: Theses on Hope and Despair),[14][15] which suggested that self-organized social groups could gradually expand the spheres of civil society in a totalitarian state, helped to inspire the dissident movements of the 1970s that led to Solidarity and eventually to the collapse of Communist rule in Eastern Europe in 1989.[citation needed] In the 1980s, Kołakowski supported Solidarity by giving interviews, writing and fundraising.[3]

Kołakowski maintained throughout his life and career a view of Marxism that was distinct from that of existing political regimes, and he relentlessly disputed these differences and defended his own interpretation of Marxism. In a famous article cleverly entitled "What is Left of Socialism", he wrote

The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia had nothing to do with Marxian prophesies. Its driving force was not a conflict between the industrial working class and capital, but rather was carried out under slogans that had no socialist, let alone Marxist, content: Peace and land for peasants. There is no need to mention that these slogans were to be subsequently turned into their opposite. What in the twentieth century perhaps comes closest to the working class revolution were the events in Poland of 1980-81: the revolutionary movement of industrial workers (very strongly supported by the intelligentsia) against the exploiters, that is to say, the state. And this solitary example of a working class revolution (if even this may be counted) was directed against a socialist state, and carried out under the sign of the cross, with the blessing of the Pope.[16]

In Poland, Kołakowski is regarded as a philosopher and historian of ideas but also as an icon for anti-communism and opponents of communism. Adam Michnik has called Kołakowski "one of the most prominent creators of contemporary Polish culture".[17][18]

Kołakowski died on 17 July 2009, aged 81, in Oxford, England.[19] In an obituary, philosopher Roger Scruton wrote that Kołakowski was a "thinker for our time" and that, regarding Kołakowski's debates with intellectual opponents, "even if ... nothing remained of the subversive orthodoxies, nobody felt damaged in their ego or defeated in their life's project, by arguments which from any other source would have inspired the greatest indignation".[20]

Awards

In 1986, the National Endowment for the Humanities selected Kołakowski for the Jefferson Lecture. Kołakowski's lecture "The Idolatry of Politics",[21] was reprinted in his collection of essays Modernity on Endless Trial.[22]

In 2003, the Library of Congress named Kołakowski the first winner of the John W. Kluge Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Humanities.[23][24]

His other awards include the following:

- Jurzykowski Prize (1969)

- Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (1977)

- Veillon Foundation European Prize for the Essay (1980)

- Erasmus Prize (1983)

- MacArthur Fellowship (1983)

- Jefferson Lecture for the National Endowment for the Humanities (1986)

- Award of the Polish Pen Club (1988)

- University of Chicago Press, Gordon J. Laing Award (1991)

- Tocqueville Prize (1994)

- Honorary degree of the University of Gdańsk (1997)[25]

- Order of the White Eagle (1997)

- Honorary degree of the University of Wrocław (2002)

- Kluge Prize of the Library of Congress (2003)[26]

- St George Medal (2006)

- Honorary degree of the Central European University (2006)

- Jerusalem Prize (2007)

- Democracy Service Medal (2009)

Bibliography

- Klucz niebieski, albo opowieści budujące z historii świętej zebrane ku pouczeniu i przestrodze (The Key to Heaven), 1957

- Jednostka i nieskończoność. Wolność i antynomie wolności w filozofii Spinozy (The Individual and the Infinite: Freedom and Antinomies of Freedom in Spinoza's Philosophy), 1958

- 13 bajek z królestwa Lailonii dla dużych i małych (Tales from the Kingdom of Lailonia and the Key to Heaven), 1963. English edition: Hardcover: University of Chicago Press (October 1989). ISBN 978-0-226-45039-1.

- Rozmowy z diabłem (US title: Conversations with the Devil / UK title: Talk of the Devil; reissued with The Key to Heaven under the title The Devil and Scripture, 1973), 1965

- Świadomość religijna i więź kościelna, 1965

- Od Hume'a do Koła Wiedeńskiego (the 1st edition:The Alienation of Reason, translated by Norbert Guterman, 1966/ later as Positivist Philosophy from Hume to the Vienna Circle),

- Kultura i fetysze (Toward a Marxist Humanism, translated by Jane Zielonko Peel, and Marxism and Beyond), 1967

- A Leszek Kołakowski Reader, 1971

- Positivist Philosophy, 1971

- TriQuartely 22, 1971

- Obecność mitu (The Presence of Myth), 1972. English edition: Paperback: University of Chicago Press (January 1989). ISBN 978-0-226-45041-4.

- ed. The Socialist Idea: A Reappraisal, 1974 (with Stuart Hampshire)

- Husserl and the Search for Certitude, 1975

- Główne nurty marksizmu. First published in Polish (3 volumes) as "Główne nurty marksizmu" (Paris: Instytut Literacki, 1976) and in English (3 volumes) as "Main Currents of Marxism" (London: Oxford University Press, 1978). Current editions: Paperback (1 volume): W. W. Norton & Company (17 January 2008). ISBN 978-0393329438. Hardcover (1 volume): W. W. Norton & Company; First edition (7 November 2005). ISBN 978-0393060546.

- Czy diabeł może być zbawiony i 27 innych kazań, 1982

- Religion: If There Is No God, 1982

- Bergson, 1985

- Le Village introuvable, 1986

- Metaphysical Horror, 1988. Revised edition: Paperback: University of Chicago Press (July 2001). ISBN 978-0-226-45055-1.

- Pochwała niekonsekwencji, 1989 (ed. by Zbigniew Menzel)

- Cywilizacja na ławie oskarżonych, 1990 (ed. by Paweł Kłoczowski)

- Modernity on Endless Trial, 1990. Paperback: University of Chicago Press (June 1997). ISBN 978-0-226-45046-9. Hardcover: University of Chicago Press (March 1991). ISBN 978-0-226-45045-2.

- God Owes Us Nothing: A Brief Remark on Pascal's Religion and on the Spirit of Jansenism, 1995. Paperback: University of Chicago Press (May 1998). ISBN 978-0-226-45053-7. Hardcover: University of Chicago Press (November 1995). ISBN 978-0-226-45051-3.

- Freedom, Fame, Lying, and Betrayal: Essays on Everyday Life, 1999

- The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, 2004

- My Correct Views on Everything, 2005

- Why Is There Something Rather Than Nothing?, 2007

- Is God Happy?: Selected Essays, 2012

- Jezus ośmieszony. Esej apologetyczny i sceptyczny, 2014

See also

- Agnieszka Kołakowska, his daughter

- Zygmunt Bauman

- Adam Schaff

- History of philosophy in Poland

- List of Polish people – philosophy

- Poles in the United Kingdom

References

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski, "The Idolatry of Politics," reprinted in Modernity on Endless Trial (University of Chicago Press, 1990, paperback edition 1997), ISBN 0-226-45045-7, ISBN 0-226-45046-5, ISBN 978-0-226-45046-9, p. 158.

- ^ Roger Kimball, Leszek Kołakowski and the Anatomy of Totalitarianism. The New Criterion, June 2005

- ^ a b Jason Steinhauer (2015). "'The Awakener of Human Hopes': Leszek Kolakowski", John W. Kluge Center at Library of Congress, September 18, 2015; accessed 01 December 2017

- ^ "Philosopher Awarded Library's New Kluge Prize". Washington Post. 11 May 2003.

- ^ "Leszek Kolakowski: Polish-born philosopher and writer who produced". Independent.co.uk. 29 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Pięć lat temu zmarł Leszek Kołakowski". 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Leszek Kolakowski". Telegraph.co.uk. 20 July 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Foreign News: VOICE OF DISSENT, TIME Magazine, 14 October 1957

- ^ Clive James (2007) Cultural Amnesia, p. 353

- ^ Gareth Jones (17 July 2009) "Polish philosopher and author Kołakowski dead at 81". Reuters

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek (2005). Main Currents of Marxism. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. p. 909. ISBN 9780393329438.

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek (1982). Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. ASIN B01JXSH3HM., p.16

- ^ Leszek Kolakowski: Scholar and Activist The Long Career of the Kluge Prize Winner, Library of Congree Information Bulletin, December 2003

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski (1971): Hope and Hopelessness. In: Survey, vol. 17, no. 3 (80)

- ^ Kołakowski : In Stalin's Countries: Theses on Hope and Despair (1971). osaarchivum.org

- ^ "What Is Left of Socialism by Leszek Kolakowski | Articles | First Things".

- ^ Adam Michnik (18 July 1985) "Letter from the Gdansk Prison," New York Review of Books.

- ^ Norman Davies (5 October 1986) "True to Himself and His Homeland," New York Times.

- ^ Leszek Kolakowski. Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Scruton, Roger. "Leszek Kolakowski: thinker for our time". opendemocracy.net. Open Democracy. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Jefferson Lecturers. neh.gov

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski (1990) "The Idolatry of Politics," p. 158 in Modernity on Endless Trial. University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-45045-7.

- ^ "Library of Congress Announces Winner of First John W. Kluge Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Humanities and Social Sciences". Loc.gov. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski, "What the Past is For" (speech given on 5 November 2003, on the occasion of the awarding of the Kluge Prize to Kołakowski).

- ^ "Doktorzy Honorowi Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego". Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "John W. Kluge Prize for Achievement in the Study of Humanity (The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

Further reading

- Azurmendi, Joxe & Arregi, Joseba: Kołakowski, Oñati: EFA, 1972. ISBN 8472400530.

External links

- "Leszek Kołakowski". Information Processing Centre database (in Polish).

- Leszek Kołakowski – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Polish Philosophy Page: Bibliography at the Wayback Machine (archived 10 January 2008)

- Kołakowski, Leszek (1974). "My correct views on everything: A rejoinder to Edward Thompson's 'Open letter to Leszek Kołakowski'". Socialist Register. 11.

- The Alienation of Reason (Extract)

- The Death of Utopia Reconsidered

- The Complete and Brief Metaphysics

- Judt, Tony. "Goodbye to All That?" in The New York Review of Books, Vol. 53, No. 14, 21 September 2006 (review-essay on Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders, the Golden Age, the Breakdown by Leszek Kołakowski, translated from the Polish by P.S. Falla. Norton, 2005, ISBN 0-393-06054-3; My Correct Views on Everything by Leszek Kołakowski, edited by Zbigniew Janowski. St. Augustine's, 2004, ISBN 1-58731-525-4; Karl Marx ou l'esprit du monde by Jacques Attali. Paris: Fayard, 2005, ISBN 2-213-62491-7)

- Kołakowski : In Stalin's Countries: Theses on Hope and Despair (1971)

- 1 April 1999, BBC Radio program In Our Time

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1927 births

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century Polish philosophers

- 21st-century Polish philosophers

- Critics of Marxism

- European democratic socialists

- Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

- Former Marxists

- Historians of communism

- Jerusalem Prize recipients

- MacArthur Fellows

- Marxist humanists

- McGill University faculty

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- People from Radom

- Polish anti-communists

- Polish emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Polish dissidents

- Polish United Workers' Party members

- Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)

- Scholars of Marxism

- Spinoza scholars

- Spinozist philosophers

- University of Warsaw alumni

- University of Warsaw faculty

- Fellows of the British Academy

- People associated with the magazine "Kultura"