Man

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Masculism |

|---|

|

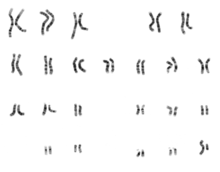

A man is an adult human male.[1][2] Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the father. Sex differentiation of the male fetus is governed by the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. During puberty, hormones which stimulate androgen production result in the development of secondary sexual characteristics, thus exhibiting greater differences between the sexes. These include greater muscle mass, the growth of facial hair and a lower body fat composition.

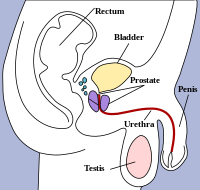

Male anatomy is distinguished from female anatomy by the male reproductive system, which includes the penis, testicles, sperm duct, prostate gland and the epididymis, as well as secondary sex characteristics.

Etymology and terminology

The English term "man" is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *man- (see Sanskrit/Avestan manu-, Slavic mǫž "man, male").[3] More directly, the word derives from Old English mann. The Old English form primarily meant "person" or "human being" and referred to men, women, and children alike. The Old English word for "man" as distinct from "woman" or "child" was wer. Mann only came to mean "man" in Middle English, replacing wer, which survives today only in the compound "werewolf" (from Old English werwulf, literally "man-wolf").[4][5]

Biology

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2019) |

In humans, sperm cells normally carry either an X or a Y sex chromosome. If a sperm cell carrying a Y chromosome fertilizes the female ova, the offspring will be male (XY). The SRY gene is normally found on the Y chromosome and is the testis determining factor that governs male sex differentiation . Sex differentiation in males proceeds in a testes dependent way while female differentiation is not gonad dependent.[6]

Humans exhibit sexual dimorphism in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, although most of these characteristics do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than women, but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species.

Primary sex characteristics (or sex organs) are characteristics that are present at birth and are integral to the reproductive process. For men, primary sex characteristics include the penis and testicles. Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans.[7][8] Such features are especially evident in the sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguish between the sexes, but—unlike the primary sex characteristics—are not directly part of the reproductive system.[9][10][11] Secondary sexual characteristics that are specific to men include:

- Facial hair;[10]

- Chest hair;[12]

- Broadened shoulders;[13]

- An enlarged larynx (also known as an Adam's apple);[13] and

- A voice that is significantly deeper than the voice of a child or a woman.[10]

Reproductive system

The male reproductive system includes external and internal genitalia. The male external genitalia consist of the penis, the male urethra, and the scrotum, while the male internal genitalia consist of the testes, the prostate, the epididymis, the seminal vesicle, the vas deferens, the ejaculatory duct, and the bulbourethral gland.[14]

The male reproductive system's function is to produce semen, which carries sperm and thus genetic information that can unite with an egg within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's uterus and then fallopian tubes goes on to fertilize an egg which develops into a fetus or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the gestation. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called andrology.

Sex hormones

Testosterone stimulates the development of the Wolffian ducts, the penis, and closure of the labioscrotal folds into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the anti-Müllerian hormone, which inhibits the development of the Müllerian ducts. For males during puberty, testosterone, along with gonadotropins released by the pituitary gland, stimulates spermatogenesis.

Health

Men have lower life expectancy[15] and higher suicide rates[16] compared to women.

Sexuality and gender

Male sexuality and attraction vary from person to person, and a man's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, including evolved predispositions, personality, upbringing, and culture. While the majority of men are heterosexual, significant minorities are homosexual or bisexual.[17]

Trans men have a male gender identity that does not align with their female sex assignment at birth and may undergo masculinizing hormone replacement therapy and/or sex reassignment surgery, while intersex men may have sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of male biology.[18] A 2016 systemic review estimated that 0.256% of people self-identify as female-to-male transgender.[19] A 2017 survey of 80,929 Minnesota students found that roughly twice as many female-assigned adolescents self-identified as transgender, compared to adolescents with a male sex assignment.[20]

Masculinity

This section duplicates the scope of other articles, specifically Masculinity. |

Masculinity (also sometimes called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with boys and men. Although masculinity is socially constructed,[21] some research indicates that some behaviors considered masculine are biologically influenced.[22] To what extent masculinity is biologically or socially influenced is subject to debate.[22] It is distinct from the definition of the biological male sex, as both males and females can exhibit masculine traits.[23]

Standards of manliness or masculinity vary across different cultures and historical periods.[24] While the outward signs of masculinity look different in different cultures, there are some common aspects to its definition across cultures. In all cultures in the past, and still among traditional and non-Western cultures, getting married is the most common and definitive distinction between boyhood and manhood.[25] In the late 20th century, some qualities traditionally associated with marriage (such as the "triple Ps" of protecting, providing, and procreating) were still considered signs of having achieved manhood.[25][26]

Anthropology has shown that masculinity itself has social status, just like wealth, race and social class. In Western culture, for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status. Many English words such as virtue and virile (from the Indo-European root vir meaning man) reflect this.[27][28]

Sex symbol

The Mars Symbol (♂) is a common symbol that represents the male sex.[29] The symbol is identical to the planetary symbol of Mars.[30] It was first used to denote sex by Carl Linnaeus in 1751. The symbol is sometimes seen as a stylized representation of the shield and spear of the Roman god Mars. According to Stearn, however, this derivation is "fanciful" and all the historical evidence favours "the conclusion of the French classical scholar Claude de Saumaise (Salmasius, 1588–1683)" that it is derived from θρ, the contraction of a Greek name for the planet Mars, which is Thouros.[31]

See also

Dynamics

Medical

Political

References

- ^ "man". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Definition of MAN". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary, Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. man-1 Archived 19 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 22 July 2007.

- ^ Rauer, Christine (January 2017). "Mann and Gender in Old English Prose: A Pilot Study". Neophilologus. 101 (1): 139–158. doi:10.1007/s11061-016-9489-1. hdl:10023/8978. S2CID 55817181.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary s.v. "man" Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ {{cite journal |last1=Rey |first1=Rodolfo |last2=Josso |first2=Nathalie |last3=Racine |first3=Chrystèle |title=Sexual Differentiation |journal=Endotext |date=2000 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279001/ |publisher=MDText.com, Inc.}|quote= Irrespective of their chromosomal constitution, when the gonadal primordia differentiate into testes, all internal and external genitalia develop following the male pathway. When no testes are present, the genitalia develop along the female pathway. The existence of ovaries has no effect on fetal differentiation of the genitalia. The paramount importance of testicular differentiation for fetal sex development has prompted the use of the expression "sex determination" to refer to the differentiation of the bipotential or primitive gonads into testes.}

- ^ Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM (2011). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1054. ISBN 978-1437736007.

- ^ Pack PE (2016). CliffsNotes AP Biology, 5th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 219. ISBN 978-0544784178.

- ^ Bjorklund DF, Blasi CH (2011). Child and Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach. Cengage Learning. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-1133168379.

- ^ a b c "Primary & Secondary Sexual Characteristics". Sciencing.com. 30 April 2018.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Elsevier Science. 2018. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-12-815145-7.

- ^ "Secondary sexual characteristics". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ a b Berger, Kathleen Stassen (2005). The Developing Person Through the Life Span. Worth Publishers. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7167-5706-1.

- ^ "Definition of Male genitalia". MedicineNet.

- ^ "Why is life expectancy longer for women than it is for men?". Scientific American. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Walton, Alice G. "The Gender Inequality of Suicide: Why Are Men at Such High Risk?". Forbes. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- ^ "what are Answers to Your Questions About Transgender Individuals and Gender Identity". APA. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Collin, Lindsay; Reisner, Sari L.; Tangpricha, Vin; Goodman, Michael (2016). "Prevalence of Transgender Depends on the "Case" Definition: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (4): 613–626. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.001. PMC 4823815. PMID 27045261.

- ^ Goodman, Michael; Adams, Noah; Corneil, Trevor; Kreukels, Baudewijntje; Motmans, Joz; Coleman, Eli (1 June 2019). "Size and Distribution of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Populations: A Narrative Review". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. Transgender Medicine. 48 (2): 303–321. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2019.01.001. ISSN 0889-8529. PMID 31027541. S2CID 135439779.

- ^ Shehan, Constance L. (2018). Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender. Gale, Cengage Learning. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9781535861175.

- ^ a b Social vs biological citations:

- Shehan, Constance L. (2018). Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender. Gale, Cengage Learning. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9781535861175.

- Martin, Hale; Finn, Stephen E. (2010). Masculinity and Femininity in the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-0-8166-2444-7.

- Lippa, Richard A. (2005). Gender, Nature, and Nurture (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 153–154, 218–225. ISBN 9781135604257.

- Wharton, Amy S. (2005). The Sociology of Gender: An Introduction to Theory and Research. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-1-40-514343-1.

- ^ Male vs Masculine/Feminine:

- Ferrante, Joan (January 2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 269–272. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1.

- "What do we mean by 'sex' and 'gender'?". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014.

- Halberstam, Judith (2004). "'Female masculinity'". In Kimmel, Michael S.; Aronson, Amy (eds.). Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 294–5. ISBN 978-1-57-607774-0.

- ^ Kimmel, Michael S.; Aronson, Amy, eds. (2004). Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-1-57-607774-0.

- ^ a b Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen (1998). "Learning to Stand Alone: The Contemporary American Transition to Adulthood in Cultural and Historical Context". Human Development. 41 (5–6): 295–315. doi:10.1159/000022591. ISSN 0018-716X. S2CID 143862036.

- ^ Gilmore, David D. (1990). Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity. Yale University Press. pp. 48. ISBN 0-300-05076-3.

- ^ "Virtue (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Virile (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ Schott, G D (24 December 2005). "Sex symbols ancient and modern: their origins and iconography on the pedigree". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 331 (7531): 1509–1510. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1509. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1322246. PMID 16373733.

- ^ "Solar System Symbols". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Stearn, William T. (1962). "The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology". Taxon. 11 (4): 109–113. doi:10.2307/1217734. ISSN 0040-0262. JSTOR 1217734.

Further reading

- Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, bell hooks, The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation, MIT Press 1995

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001

- Robert W. Connell, Masculinities, Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995

- Warren Farrell, The Myth of Male Power Berkley Trade, 1993 ISBN 0-425-18144-8

- Michael Kimmel (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, Sage Publications 2004