Marine Corps War Memorial

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

| Marine Corps War Memorial | |

|---|---|

| United States of America | |

Marine Corps War Memorial | |

| For the Marine dead of all wars, and their comrades of other services who fell fighting beside them. | |

| Unveiled | November 10, 1954 70 years ago |

| Location | 38°53′25.7″N 77°04′10.85″W / 38.890472°N 77.0696806°W near |

| Designed by | Felix de Weldon (sculptor) Horace W. Pealee (architect) |

Uncommon Valor Was A Common Virtue In Honor And Memory Of The Men Of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775 | |

The United States Marine Corps War Memorial (Iwo Jima Memorial) is a national monument in Arlington, Virginia, United States. Dedicated 70 years ago in 1954,[1] it is located in Arlington Ridge Park, at the back entrance to Arlington National Cemetery and next to the Netherlands Carillon. The war memorial is dedicated to all U.S. Marine Corps personnel who have died in the defense of the United States since 1775.

The memorial was inspired by the iconic 1945 photograph of six Marines raising a U.S. flag atop Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II.[2] It was taken by Associated Press combat photographer Joe Rosenthal. Upon first seeing the photograph, sculptor Felix de Weldon created a maquette for a sculpture based on it in a single weekend. He and architect Horace W. Peaslee designed the memorial. Their proposal was presented to Congress, but funding was not possible during the war. In 1947, a federal foundation was established to raise funds for the memorial.

History

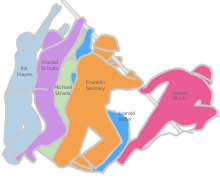

Left to right: Ira Hayes, Harold Schultz, Michael Strank, Franklin Sousley, Rene Gagnon, and Harlon Block

.

The centerpiece of the memorial is a colossal sculpture group depicting the six Marines who raised the second (and larger) replacement U.S. flag atop Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945. They were: Marine Sergeant Michael Strank, Corporal Harlon Block, Private First Class Rene Gagnon, Private First Class Ira Hayes, Private First Class Franklin Sousley, and Private First Class Harold Schultz.[3][4]

The flag-raising also was recorded by Marine Staff Sergeant Bill Genaust, a combat motion picture cameraman, who filmed the event in color while standing beside Rosenthal. Genaust's footage was included in the 1945 newsreel "Carriers Hit Tokyo," and established that the second flag raising was not staged. He was killed by the Japanese after entering a cave on Iwo Jima during the battle. Genaust's remains have never been found.

The commission for the memorial was awarded in 1951. De Weldon spent three years creating a full-sized master model in plaster, with figures 32 feet (9.8 m) tall. This was disassembled like a giant puzzle, and each piece was separately cast in bronze. Peaslee's base for the memorial is made of black diabase granite from a quarry in Lönsboda, a small town in the southernmost province of Sweden.[5] It features a number of inscriptions. Construction of the memorial began in September 1954. The bronze pieces of the sculpture were assembled, to which was added a 60 feet (18 m) flagpole. The total cost of the memorial was $850,000, including the development of the site. It was paid for with donations, mostly from U.S. Marines; no public funds were used.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was among the many dignitaries who attended the memorial's dedication on November 10, 1954, the 179th anniversary of the founding of the Marine Corps.[1] The memorial was presented to the American people by General Lemuel Shepherd, the Commandant of the Marine Corps.[6] In 1961, President John F. Kennedy issued a proclamation on June 12 that a Flag of the United States should fly over the memorial 24 hours a day, one of the few official sites where this is required.[7]

The memorial is located on a high ridge, overlooking the national capital. The Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C. uses the memorial as the centerpiece of its weekly Sunset Parade, featuring the Drum and Bugle Corps and the Silent Drill Platoon.

Memorial inscriptions

The memorial consists of front and rear inscriptions, and inscribed in gold letters around the polished black granite upper base of the memorial is the date and location of every United States Marine Corps major action up to the present time.

Front (west side): "Uncommon Valor Was A Common Virtue" - "Semper Fidelis"

Rear (east side): "In Honor And Memory Of The Men Of The United States Marine Corps Who Have Given Their Lives To Their Country Since 10 November 1775"

Felix de Weldon's and Joe Rosenthal's names are also inscribed on the bottom left and bottom right base of the front side of the memorial. Rosenthal's name was added in 1982.

Memorial marker

"Dedicated To The Marine Dead Of All Wars, And Their Comrades Of Other Services Who Fell Fighting Beside Them.

Created By Felix De Weldon, And Inspired By The Immortal Photograph Taken By Joseph J. Rosenthal On February 23, 1945, Atop Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands.

Erected By The Marine Corps War Memorial Foundation, With Funds Provided By Marines And Their Friends, And With The Cooperation And Support Of Many Public Officials.

Dedicated November 10, 1954"

Memorial rumor and criticism

A persistent rumor has attributed the existence of a thirteenth hand from the six statues of the men depicted on the memorial and speculation about the possible reasons for it. When informed of the rumor, de Weldon exclaimed, "Thirteen hands. Who needed 13 hands? Twelve were enough."[8]

In the siting controversy for the U.S. Air Force Memorial, originally to be near de Weldon's work, J. Carter Brown (in 1998, chairman of the United States Commission of Fine Arts) described the Marine Corps Memorial as, "I would say that the Iwo Jima memorial is kitsch. It was taken from a photograph, it is by a sculptor, even though he was a member of this commission at one point, who is not going to go down as a Michelangelo in history—and yet it is very effective, largely because of its site." This remark was met with calls for Brown's resignation from the commission, and disagreement over the categorization from the commission's staff.[9]

Refurbishment

On April 29, 2015, philanthropist David Rubenstein pledged over five million dollars to refurbish the memorial in honor of his father, a Marine veteran from World War II who died in 2013, "and all Marines who have died in service to the United States." The $5.37 million donation, made through the National Park Foundation, will support cleaning and waxing the statue, polishing the black granite panels, regilding inscriptions, relandscaping, and making repairs to the pavement, lighting and flagpole. Most of the work, expected to last two years, will be done in 2016.[10] While the Park Service performs regular routine maintenance, this will the first comprehensive refurbishment of the memorial since its dedication in 1954.[11]

-

Sculptor Felix de Weldon with his master model.

-

De Weldon's remarks at the 1954 dedication of the Memorial.

Related memorials

When there were no government funds for sculpture during the war, the sculptor financed a concrete version of similar design in a one-third size that was placed on a parcel of land in Washington, D.C. until 1947, when it was put into storage. It later was restored and displayed at a museum on an aircraft carrier and again, returned to storage. This small concrete statue of the second U.S. flag raising at Iwo Jima in 1945 was scheduled to be auctioned in February 2013 at a New York auction dedicated to World War II artifacts,[12] but it failed to receive the minimum bid required for the auction of it to begin.

The original plaster working model for the bronze and granite memorial statue currently stands in Harlingen, Texas at the Marine Military Academy, a private Marine Corps-inspired youth military academy. The academy also is the final resting place of Corporal Block, one of the flag raisers who was killed in action on Iwo Jima.

A small model stands in the lobby of Spruance Hall, U.S. Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island. It was presented by the sculptor, a resident of Newport.

There also are scaled-down replicas at three Marine bases: just outside the front gate of Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia, adjacent to the parade deck at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island in South Carolina, and just inside the main gate at Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kāne'ohe Bay, Hawaii.

A version of the memorial dedicated in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of World War II stands in the Knoebels Amusement Resort in Elysburg, Pennsylvania.

A similar design is used for the National Iwo Jima Memorial in Newington, Connecticut , which was dedicated in 1995 to the 6,821 U.S. servicemen who died in the battle.

Other copies of the statue are located at Cape Coral, Florida and Fall River Bicentennial Park in Massachusetts.[13][14]

A plywood cutout version is found along Highway 62 ca. 17 miles from the center of Twentynine Palms, California.

-

The 5th Marine Division Memorial, at the U.S. flag-raising site on Mount Suribachi, Iwo Jima.

-

Marine Corps Memorial, Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia.

-

Iwo Jima Memorial, Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina.

-

Pacific War Memorial, Marine Corps Base Hawaii.

-

War Memorial (1973), U.S. Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island

-

Iwo Jima Monument (1982), Marine Military Academy, Harlingen, Texas.

-

National Iwo Jima Memorial (1995), Newington, Connecticut

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

- ^ a b "Memorial honoring Marines dedicated". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 1.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (May 2, 2016). "Marine Corps investigating photo of iconic flag-raising on Iwo Jima". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- ^ http://www.gemeneman.se/MinSommar2005.pdf (in Swedish) Translation, page 3 line 28-29: The most famous war memorial in the United States, U.S. Marine Corps Memorial in Washington D.C., stands on a base in granite pieces from Hägghult. Hägghult is the name of the quarry, just outside Lönsboda.

- ^ "Marine monument seen as symbol of hopes, dreams". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. November 10, 1954. p. 2.

- ^ "Permanent flag ordered". Kentucky New Era. Hopkinsville. Associated Press. June 13, 1961. p. 3.

- ^ Kelly, John (February 23, 2005). "One Marine's Moment". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post Company. p. C13. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 13, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Iwo Jima memorial called 'kitsch'". Deseret News. March 8, 1998. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. (April 29, 2015). "Billionaire David Rubenstein gives $5M to refurbish Iwo Jima sculpture". Washington Post. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ Zongker, Brett (April 29, 2015). "Marine Corps Memorial to be restored after $5.4M donation". The Associated Press. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ "Original Iwo Jima monument could fetch up to $1.8M at NYC auction". Fox News. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ "Iwo Jima Memorial". SWFL Art & Community Theater. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ Froyd, Madeline (August 31, 2015). "195 Things: Fall River's Iwo Jima monument honors veterans". The Herald News. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

External links

- Official website

- Uncommon Valor A short USMC-created film about the Iwo Jima Memorial

- Marine Military Academy Iwo Jima monument

- USMC War Memorial photographs at WW2DB

- Marine Corps War Memorial (Marine Barracks Washington webpage)

- Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) No. VA-9, "United States Marine Corps War Memorial, Marshall Drive, Arlington, Arlington County, VA"

- 1954 establishments in Virginia

- Buildings and structures in Arlington County, Virginia

- Battle of Iwo Jima

- Landmarks in Virginia

- United States Marine Corps lore and symbols

- United States Marine Corps memorials

- Military monuments and memorials in the United States

- Visitor attractions in Arlington County, Virginia

- Monuments and memorials in Virginia

- 1954 sculptures

- Bronze sculptures in Virginia

- George Washington Memorial Parkway

- Historic American Landscapes Survey in Virginia

- Statues in Virginia

- Sculptures of men in Virginia