Neville Bonner

Neville Bonner | |

|---|---|

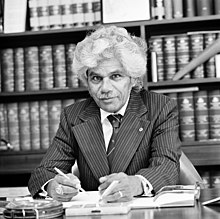

Bonner in 1979 | |

| Senator for Queensland | |

| In office 20 August 1971 – 4 February 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Dame Annabelle Rankin |

| Succeeded by | Ron Boswell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Neville Thomas Bonner 28 March 1922 Ukerebagh Island, New South Wales, Australia |

| Died | 5 February 1999 (aged 76) Ipswich, Queensland, Australia |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Mona Bonner

(m. 1943; died 1969) |

| Children | 5 boys |

| Occupation | Federal Senator |

Neville Thomas Bonner AO (28 March 1922 – 5 February 1999) was an Australian politician, and the first Aboriginal Australian to become a member of the Parliament of Australia. He was appointed by the Queensland Parliament to fill a casual vacancy in the representation of Queensland in the Senate, and later became the first Indigenous Australian to be elected to the parliament by popular vote. Neville Bonner was an elder of the Jagera people.

Early life

Bonner was born on 28 March 1922 on Ukerebagh Island, a small island in the Tweed River of New South Wales close to the border with Queensland. He was the son of Julia Bell, an Indigenous Australian, and Henry Kenneth Bonner, an English immigrant. His maternal grandmother Ida Sandy was a member of the Ugarapul people of the Logan and Albert Rivers, while his maternal grandfather Roger Bell (or Jung Jung) was a fully initiated member of the Yagara people of the Brisbane River. According to Bonner, his grandfather was "sort of captured [...] out of the tribe" as a young boy and given an English name.[1]

Bonner's parents met and married in Murwillumbah, New South Wales. His father abandoned his mother when she was pregnant with him, leaving her destitute. She subsequently moved to the Aboriginal reserve on Ukerebagh Island, where she had another son. After about five years, the family moved near Lismore, New South Wales, to be closer to Bonner's grandparents, living on the banks of the Richmond River under a lantana bush. His mother subsequently had three children with Frank Randell, an Aboriginal man who was employed by the local police. One of his half-brothers died as a child and he "witnessed frequent acts of violence by Randell against his mother".[1]

Bonner's mother died in July 1932, when he was ten years old, and his grandmother subsequently became his main caregiver. She moved the family to Beaudesert, Queensland, where in 1935 he completed his only year of formal education at Beaudesert State Rural School. His grandmother died in June 1935 and he moved back to New South Wales after finishing the school year.[1] Bonner worked as a ring barker, cane cutter and stockman before settling on Palm Island, near Townsville, Queensland in 1946, where he rose to the position of Assistant Settlement Overseer.[2]

Contribution to Parliament

In 1960 he lived in Ipswich, where he joined the board of directors of the One People of Australia League (OPAL),[3] a moderate Indigenous rights organisation. He became its Queensland president in 1970. He joined the Liberal Party in 1967 and held local office in the party. Following the resignation of Senator Annabelle Rankin in 1971, Bonner was chosen to fill the casual vacancy and he became the first Indigenous Australian to sit in the Australian Parliament. He was elected in his own right in 1972, 1974, 1975, and 1980.

While in the Senate he served on a number of committees but was never a serious candidate for promotion to the ministry. He rebelled against the Liberal Party line on some issues. Partly as a result of this, and partly due to pressure from younger candidates, he was dropped from the Liberal Senate ticket at the 1983 election. He stood as an independent and was nearly successful. The Hawke government then appointed him to the board of directors of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Bonner was almost unique in being an Indigenous activist and a political conservative: in fact he owed his political career to this combination. In the face of often savage personal criticism from left-wing Indigenous activists, he often denied being a "token" in the Liberal Party. In 1981 Bonner was the only government voice opposing a bill put forth that would allow drilling in the Great Barrier Reef. He regularly "crossed the floor" on bills, a characteristic that has endeared him to politicians today but is often considered the reason for his political career coming to an end.[4]

In 1979 Bonner was jointly named Australian of the Year[5] along with naturalist Harry Butler. In 1984 Bonner was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia.[6] From 1992 to 1996 he was member of the Griffith University Council. The university awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1993. In 1998 he was elected to the Constitutional Convention as a candidate of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy.

Bonner died at Ipswich in 1999, aged 76.

Bonner's grand niece Joanna Lindgren was the first female Aboriginal senator for Queensland when she represented the Liberal National Party from May 2015 to July 2016.

Posthumous honours

The Neville Bonner Memorial Scholarship was established by the federal government in 2000 and is now considered Australia's most prestigious scholarship for Indigenous Australians to study Honours in Political Science or related subjects at any recognised Australian university.[7]

The Queensland federal electorate of Bonner was created in 2004 and was named in his honour. Also, a recently re-developed rugby league oval in Ipswich was named the Neville Bonner Sporting Complex in his honour. This oval was formerly home to an exclusively Indigenous side, but is now the official home of the Queensland Cup side, the Ipswich Jets, and the IRL/IJRL finals and junior representative. The suburb of Bonner in Canberra, Australia's national capital, also bears his name.

The head office of the Queensland Department of Communities, Child Safety and Disability services in Brisbane was named the Neville Bonner Building.[8] A multipurpose 47-bed hostel, managed by Aboriginal Hostels Limited, located in the Rockhampton suburb of Berserker is called the Neville Bonner Hostel.[9]

Bonner was an active boomerang enthusiast. One of his boomerangs was placed on display at the Old Parliament House in Canberra.[10]

The Neville Bonner Bridge is scheduled to open in Brisbane in 2022.[11]

Personal life

Bonner married Mona Banfield in 1943, in a Catholic ceremony at Palm Island's mission.[1] They had five sons and fostered three daughters. Mona Bonner died in 1969. Neville married Heather Ryan in 1972.[12]

Bonner was taught to make boomerangs by his grandfather. In 1966, he established a boomerang manufacturing business named Bonnerang, with the assistance of his family. The boomerangs were handmade from the roots of black wattle trees, as Bonner refused to use synthetic materials. His company produced up to 450 boomerangs per week, but folded after a year due to a shortage of wood. After being elected to parliament, Bonner gave a boomerang demonstration in the gardens of Parliament House. In his maiden speech he called on the intellectual property of the boomerang to be reserved for Indigenous people, as non-Indigenous people were producing cheap synthetic properties. One of his boomerangs is held by the Museum of Australian Democracy.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Rowse, Tim (2010). "Bonner, Neville Thomas (1922–1999)". The Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate. Vol. 3. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Neville Bonner - Biographical Information". Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ One People of Australia League Archived 13 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ On this day: Australia's first indigenous MP born, Australian Geographic, 27 March 2015

- ^ Lewis, Wendy (2010). Australians of the Year. Pier 9 Press. ISBN 978-1-74196-809-5.

- ^ "It's an Honour - Honours - Search Australian Honours". Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ ANU: Office of the Vice-Chancellor

- ^ "Projects | Architecture, urban design, planning and interiors | Architectus".

- ^ "Neville Bonner Hostel". Aboriginal Hostels Limited. Australian Government. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "boomerangs-neville-bonner-traditional-boomerang – Boomerang Association of Australia". Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ name=Neville Bonner Bridge Grimshaw Architects

- ^ "WARM-HEARTED MR. BONNER MAKES HISTORY". Australian Women's Weekly (1933 - 1982). 9 June 1971. p. 7. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Boomerang #2006-2443". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

Further reading

- Burger, Angela (1979). Neville Bonner: A Biography. Macmillan. ISBN 0333252365.

- Jacobs, Sean. Neville Bonnr. Connor Court Publishing. ISBN 9781922449719.

External links

- Listing of Neville Bonner's life in published media & books

- Classroom Resource

- Episode on Bonner's life and career on Australian Broadcasting Corporation Radio National's Hindsight program

←

- Board members of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- 1922 births

- 1999 deaths

- Indigenous Australian politicians

- Liberal Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia

- Australian monarchists

- Members of the Australian Senate

- Members of the Australian Senate for Queensland

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- Australian of the Year Award winners

- Australian Roman Catholics

- Delegates to the Australian Constitutional Convention 1998

- People from the Northern Rivers

- Independent members of the Parliament of Australia

- 20th-century Australian politicians