Rakshasa

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) |

Rakshasa as depicted in Yakshagana, an art form of Uttara Kannada. Artist: Krishna Hasyagar, Karki | |

| Grouping | Demigod |

|---|---|

| Similar entities | Asura |

| Folklore | |

| Other name(s) |

|

| Country | India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia |

Rākshasa (Sanskrit: राक्षस, IAST: rākṣasa, pronounced [raːkʂɐsɐ]; Pali: rakkhasa; lit. "preservers")[1] are a race of usually malevolent beings prominently featured in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Folk Islam. They reside on Earth but possess supernatural powers, which they usually use for evil acts such as disrupting Vedic sacrifices or eating humans.[2][3]

The term is also used to describe asuras, a class of power-seeking beings that oppose the benevolent devas. They are often depicted as antagonists in Hindu scriptures, as well as in Buddhism and Jainism. The female form of rakshasa is rakshasi.[4]

Hinduism

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In Puranas

[edit]Brahmā, in a form composed of the quality of foulness, produced hunger, of whom anger was born: and the god put forth in darkness beings emaciate with hunger, of hideous aspects, and with long beards. Those beings hastened to the deity. Such of them as exclaimed, “Oh preserve us!” were thence called Rākṣasas.[5] Those created beings, overwhelmed by hunger, attempted to seize the waters. Those among them who said—“we shall protect these waters”, are remembered as Rākṣasas.[6]

Description

[edit]Rakshasas were most often depicted as shape-shifting, fierce-looking, enormous monstrous-looking creatures, with two fangs protruding from the top of the mouth and having sharp, claw-like fingernails. They were shown as being mean, growling beasts, and as insatiable man-eaters that could smell the scent of human flesh. Some of the more ferocious ones were shown with flaming red eyes and hair, drinking blood with their cupped hands or from human skulls (similar to representations of vampires in later Western mythology). Generally they could fly, vanish, and had maya (magical powers of illusion), which enabled them to change size at will and assume the form of any creature. The female equivalent of rakshasa is rakshasi.[7]

In Hindu epics

[edit]In the world of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Rakshasas were a populous race. There were both good and evil rakshasas, and as warriors they fought alongside the armies of both good and evil. They were powerful warriors, expert magicians and illusionists. As shape-changers, they could assume different physical forms. As illusionists, they were capable of creating appearances which were real to those who believed in them or who failed to dispel them. Some of the rakshasas were said to be man-eaters, and made their gleeful appearance when the slaughter on a battlefield was at its worst. Occasionally they served as rank-and-file soldiers in the service of one or another warlord.

Aside from their treatment of unnamed rank-and-file Rakshasas, the epics tell the stories of certain members of these beings who rose to prominence, sometimes as heroes but more often as villains.

Thapar suggests that the Rakshasas could represent exaggerated, supernatural depictions of demonized forest-dwellers who were outside the caste society.[8]

In the Rāmāyaṇa

[edit]In books 3-6 of the Rāmāyaṇa, the rākṣasas are the main antagonists of the narrative. The protagonist Rāma slays many rākṣasas throughout the epic, including Tāṭakā, Mārīca, and Rāvaṇa.[3] In the epic, the rākṣasas are portrayed as mainly demonic beings who are aggressive and sexual. They can assume any form they wish, which Rāvaṇa uses to good effect to trick and kidnap Sītā, Rāma's wife, which drives the rest of the narrative. The rākṣasas reside in the forests south of the Gangetic plain and in the island fortress of Laṅkā, both far away from the lands of Kosala and the home of Rāma. In Laṅkā, the capital of Rāvaṇa, the rākṣasas live in a complex society comparable to the humans of Ayodhyā, where some rākṣasas such as Vibhīṣaṇa are moral beings.[9]

In the Mahabharata

[edit]The Pandava hero Bhima was the nemesis of forest-dwelling Rakshasas who dined on human travellers and terrorized human settlements.

- Bhima killed Hidimba, a cannibal Rakshasa. The Mahabharata describes him as a cruel cannibal with sharp, long teeth and prodigious strength.[10] When Hidimba saw the Pandavas sleeping in his forest, he decided to eat them. He sent his sister Hidimbi to reconnoiter the situation, and the young woman fell in love with the handsome Bhima, whom she warned of danger. Infuriated, Hidimba declared he was ready to kill not only the Pandavas but also his sister, but he was thwarted by the heroism of Bhima, who defeated and killed him in a duel.

- Ghatotkacha, a Rakshasa who fought on the side of the Pandavas, was the son of Bhima and the Rakshasi Hidimbi, who had fallen in love with the hero and warned him of danger from her brother. Bhima killed the evil Rakshasa Hidimba. Their son's name refers to his round bald head; ghata means 'pot' and utkacha means 'head' in Sanskrit. Ghatotkacha is considered a loyal and humble figure. He and his followers were available to his father Bhima at any time; all Bhima had to do was to think of him and he would appear. Like his father, Ghatotkacha primarily fought with the mace. His wife was Ahilawati and his sons were Anjanaparvana, Barbarika, and Meghavarna.

In the Mahabharata, Ghatotkacha was summoned by Bhima to fight on the Pandava side in the Kurukshetra War. Invoking his magical powers, he wrought great havoc in the Kaurava army. In particular, after the death of Jayadratha, when the battle continued on past sunset, his powers were at their most effective (at night). After performing many heroic deeds on the battlefield and fighting numerous duels with other great warriors (including the Rakshasa Alamvusha, the elephant-riding King Bhagadatta, and Aswatthaman, the son of Drona), Ghatotkacha encountered the human hero Karna. At this point in the battle, the Kaurava leader Duryodhana had appealed to his best fighter, Karna, to kill Ghatotkacha, as the entire Kaurava army was near annihilation due to his ceaseless strikes from the air. Karna possessed a divine weapon, Shakti, granted by the god Indra. It could be used only once and Karna had been saving it to use on his arch-enemy Arjuna, the best Pandava fighter. Unable to refuse Duryodhana, Karna used the Shakti against Ghatotkacha, killing him. This is considered to be the turning point of the war. After his death, the Pandava counselor Krishna smiled, as he considered the Pandava prince Arjuna to be saved from certain death, as Karna had used the Shakta divine weapon. A temple in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, honors Ghatotkacha; it is located near the Hidimba Devi Temple.

- Bakasura was a cannibalistic forest-dwelling Rakshasa who terrorized the nearby human population by forcing them to take turns making him regular deliveries of food, including human victims. The Pandavas travelled into the area and took up residence with a local Brahmin family. Their turn came when they had to make a delivery to Bakasura, and they debated who among them should be sacrificed. The rugged Bhima volunteered to take care of the matter. Bhima went into the forest with the food delivery (consuming it on the way to annoy Bakasura). He engaged Bakasura in a ferocious wrestling match, and broke his back. The human townspeople were amazed and grateful. The local Rakshasas begged for mercy, which Bhima granted them on the condition that they give up cannibalism. The Rakshasas agreed and soon acquired a reputation for being peaceful towards humans.[11]

- Kirmira, the brother of Bakasura, was a cannibal and master illusionist. He haunted the wood of Kamyaka, dining on human travellers. Like his brother before him, Kirmira also made the mistake of fighting the Pandav hero Bhima, who killed him with his bare hands.[12]

- Jatasura was a cunning Rakshasa who, disguised as a Brahmin, attempted to steal the Pandavas' weapons and to ravish Draupadi, wife of the five Pandavas. Bhima arrived in time to intervene, and killed Jatasur in a duel.[13] Jatasur's son was Alamvush, who fought on the side of the Kauravas at Kurukshetra.

Rakshasa heroes fought on both sides in the Kurukshetra war.

- Alamvusha was a Rakshasa skilled at fighting with both conventional weapons and the powers of illusion. According to the Mahabharata, he fought on the side of the Kauravas. Arjuna defeated him in a duel,[14] as did Arjuna's son Abhimanyu.[15] But Alamvusha in turn killed Iravan, Arjuna's son by a Nāga princess Ulupi, when the Rakshasa used his powers of illusion to take on the form of Garuda.[16] Alamvusha was also defeated by Bhima.[17] He was slain by Bhima's son, the Rakshasa Ghatotkacha.[18]

Buddhism

[edit]Many Rakshasas appear in various Buddhist Scriptures. In Chinese tradition rakshasa are known as luosha (羅刹/罗刹).[19] In Japan, they are known as rasetsu (羅刹).

Chapter 26 of the Lotus Sutra includes a dialogue between the Buddha and a group of rakshasa daughters, who swear to uphold and protect the Lotus Sutra. They also teach magical dhāraṇīs to protect followers who also uphold the sutra.[20]

Five rakshasha are part of Mahakala's retinue. They are Kala and Kali, husband and wife, and their offspring Putra, Bhatri and Bharya.[21]

The Lankavatara Sutra mentions the island of Sri Lanka as land of Rakshasas. Their king is the Rakshasa called Ravana, who invites Buddha to Sri Lanka for delivering the sermon in the land. There are other Rakhasas from the land, such as Wibisana, who is believed to be the brother of Ravana in Sri Lankan Buddhist mythology.[22]

In The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava, recorded by Yeshe Tsogyal, Padmasambhava receives the nickname of "Rakshasa" during one of his wrathful conquests to subdue Buddhist heretics.

-

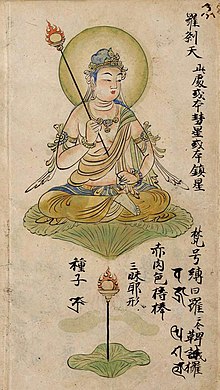

Painting of Rakshasa as one of the Twelve Devas of the Vajrayana tradition.

Japan, Heian period, 1127 CE. -

Rakshasa as a single deity, depicted on a page from a folio describing deities from the Diamond Realm and Womb Realm.

Japan, Heian period, 12th century.

Jainism

[edit]Jain accounts vary from the Hindu accounts of Rakshasa. According to Jain literature, Rakshasa was a kingdom of civilized and vegetarian people belonging to the race of Vidyadhara, who were devotees of Tirthankara.[23]

Islam

[edit]Kejawèn-influenced Indonesian Muslims view the Rakshasas as the result of people whose soul is replaced by the spirit of a devil (shayāṭīn). The devils are envious of humans and thus attempt to possess their body and minds. If they succeed, the human adapts to the new soul and gains their qualities, turning the person into a Rakshasa.[24]

Artistic and folkloric depictions

[edit]

The artists of Angkor in Cambodia frequently depicted Ravana in stone sculpture and bas-relief. The "Nāga bridge" at the entrance to the 12th-century city of Angkor Thom is lined with large stone statues of Devas and Asuras engaged in churning the Ocean of Milk. The ten-headed Ravana is shown anchoring the line of Asuras.[25]

A bas-relief at the 12th-century temple of Angkor Wat depicts the figures churning the ocean. It includes Ravana anchoring the line of Asuras that are pulling on the serpent's head. Scholars have speculated that one of the figures in the line of Devas is Ravana's brother Vibhishana. They pull on a serpent's tail to churn the Ocean of Milk.[26] Another bas-relief at Angkor Wat shows a 20-armed Ravana shaking Mount Kailasa.[27]

The artists of Angkor also depicted the Battle of Lanka between the Rakshasas under the command of Ravana and the Vanaras or monkeys under the command of Rama and Sugriva. The 12th-century Angkor Wat contains a dramatic bas-relief of the Battle of Lanka between Ravana's Rakshasas and Rama's monkeys. Ravana is depicted with ten heads and twenty arms, mounted on a chariot drawn by creatures that appear to be a mixture of horse, lion, and bird. Vibhishana is shown standing behind and aligned with Rama and his brother Lakshmana. Kumbhakarna, mounted on a similar chariot, is shown fighting Sugriva.[28]

This battle is also depicted in a less refined bas-relief at the 12th-century temple of Preah Khan.

In fiction

[edit]Rakshasa have long been a race of villains in the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game. They appear as animal-headed humanoids (generally with tiger or monkey heads) with their hands inverted (palms of its hands are where the backs of the hands would be on a human). They are masters of necromancy, enchantment and illusion (which they mostly use to disguise themselves) and are very hard to kill, especially due to their partial immunity to magical effects. They ravenously prey upon humans as food and dress themselves in fine clothing.[29] This version of the rakshasa was heavily inspired by an episode of Kolchak: The Night Stalker[30] entitled "Horror in the Heights," which aired on December 20, 1974.[citation needed]

Rakshasa appears in the Unicorn: Warriors Eternal episode "Darkness Before Dawn". He is a humanoid tiger similar to the D&D depiction. This version is a fierce but benevolent guardian of the jungle who allies with Merlin against the Evil.[31]

In the film World War Z, Rakshasa were mentioned in reference to the zombies in India.[32]

In languages

[edit]In Indonesian and Malaysian variants of Malay which have significant Sanskrit influence, raksasa now means "giant", "gigantic", "huge and strong";[33] the Malaysian variant recognises the word as an outright official equivalent to "monster"[34] whereas the Indonesian variant uses it more in colloquial usage.[33]

See also

[edit]- Asura

- Brahmarakshasa

- Daitya

- Danava

- List of Rakshasas

- Ogre

- Oni

- Troll

- Wrath of Rakshasa (Six Flags Great America Dive Coaster)

Citations

[edit]- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (18 April 2019). "God Brahmā's mental creation [Chapter 8]". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Skyes, Edgerton; Kendall, Alan; Sykes, Egerton (4 February 2014). Who's Who in Non-Classical Mythology. Routledge. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-136-41437-4.

- ^ a b Rodrigues, Hillary (2018). "Asuras, Daityas, Dānavas, Rākṣasas, Piśācas, Bhūtas, Pretas, and so forth". In Knut, A. Jacobsen; Basu, Helene; Malinar, Angelika; Narayanan, Vasudha (eds.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online. Brill.

- ^ Knappert, Jan (1991). Indian Mythology: An Encyclopedia of Myth and Legend. Aquarian Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-85538-040-0.

- ^ "The Vishnu Purana, Book 1:Chapter 8". Wisdom Library. 30 August 2014.

- ^ "The Brahmanda Purana, Section 2: Chapter 8". Wisdom Library. 18 April 2019.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 72.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2002). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-520-23899-0.

- ^ Pollock, Sheldon I. (1991). "Rākṣasas and Others". In Goldman, Robert P. (ed.). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume III: Araṇyakāṇda. Princeton University Press. pp. 68–84.

- ^ Mahabharata, Book I: Adi Parva, Section 154

- ^ Mahabharata, Book I: Adi Parva, Sections 159-166.)

- ^ Mahabharata, Book III: Varna Parva, Section 11

- ^ Mahabharata, Book III: Varna Parva, Section 156

- ^ Mahabharata, Book VII: Drona Parva, Section 167

- ^ Mahabharata, Book VI: Bhishma Parva, Section 101–102

- ^ Ganguli (1883–1896). "Section XCI". The Mahabharata Book 6: Bhishma Parva. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Mahabharata, Book VII: Drona Parva, Section 107

- ^ Mahabharata, Book VII: Drona Parva, Section 108

- ^ The Contemporary Chinese Dictionary. 2002. ISBN 7-5600-3195-1.

- ^ Lotus Sutra, chapter 26, Burton Watson translation Archived 25 March 2003 at archive.today

- ^ John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel (2003). The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Serindia Publications. p. 335. ISBN 9781932476019.

- ^ "The Lankavatara Sutra. A Mahayana Text". lirs.ru. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Jainism Resource Center - Articles". sites.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Woodward, Mark (2010). Java, Indonesia and Islam. Springer Netherlands. p. 88.

- ^ Rovedo 1997, p. 108

- ^ Rovedo 1997, pp. 108–110; Freeman & Jacques 2003, p. 62

- ^ Freeman & Jacques 2003, p. 57

- ^ Rovedo 1997, pp. 116–117

- ^ Monster Manuel Core Rulebook III V3.5 Cook, Tweet, Williams

- ^ "TSR - Q&A with Gary Gygax". 29 August 2002.

- ^ Kaldor, David (17 June 2023). "Review: Unicorn: Warriors Eternal "Darkness Before the Dawn"". Bubbleblabber. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Agrawal, Sahil (4 July 2013). ""World War Z" As Mindless As Its Undead". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ a b Atmosumarto, Sutanto (2004). A learner's comprehensive dictionary of Indonesian. Atma Stanton. p. 445. ISBN 9780954682804.

- ^ "'monster' - Kamus Bahasa Inggeris [English Dictionary]". Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

General references

[edit]- Freeman, Michael; Jacques, Claude (2003). Ancient Angkor. Bangkok: River Books.

- Rovedo, Vittorio (1997). Khmer Mythology: Secrets of Angkor. New York: Weatherhill.

Further reading

[edit]- Pollock, Sheldon (1985/1986). "Rakshasas and others" Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Indologica Taurinensia vol. 13, pp. 263–281.

External links

[edit]- The Mahabharata of Vyasa translated from Sanskrit into English by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, online version