Ravachol

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (January 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

François Claudius Koenigstein | |

|---|---|

Ravachol | |

| Born | 14 October 1859 |

| Died | 11 July 1892 (aged 32) Montbrison, France |

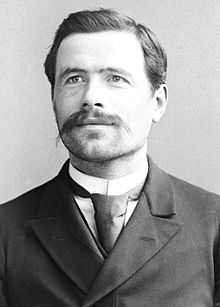

François Claudius Koenigstein, also known as Ravachol, (14 October 1859 – 11 July 1892) was a French anarchist. He was born on 14 October 1859, at Saint-Chamond, Loire and died by being guillotined on 11 July 1892, at Montbrison after being twice found guilty of complicity in bombings.

Biography

François Koenigstein was born in Saint-Chamond, Loire as the eldest child of a Dutch father (Jean Adam Koenigstein) and a French mother (Marie Ravachol). As an adult, he adopted his mother's maiden name as his surname, following years of struggle after his father abandoned the family when François was only eight years old. From that time on he had to support his mother, sister, and brother; he also looked after his nephew. He eventually found work as a dyer's assistant, a job which he later lost. He was very poor throughout his life. For additional income he played accordion at society balls on Sundays at Saint-Étienne.

The bombings

Ravachol was a grave-robber before he became politically active. He joined the anarchists as well as groups organizing to improve working conditions. Labor unrest resulted in fierce reprisals by police. On 1 May 1891, at Fourmies, a workers' demonstration took place for the eight-hour day; confrontations with the police followed. The police opened fire on the crowd, resulting in nine deaths amongst the demonstrators. The same day, at Clichy, serious incidents erupted in a procession in which anarchists were taking part. Three men were arrested and taken to the commissariat of police. There they were interrogated (and brutalised with beatings, resulting in injuries). A trial (the Clichy Affair) ensued, in which two of the three anarchists were sentenced to prison terms (despite their abuse in jail.) In addition to these events, authorities kept up repression of the communards, which had continued from the time of the insurrection of the Paris Commune of 1871.

Ravachol had fled to Spain sometime after June, 1891, in order to get away from police for a murder that took place in June against "an elderly recluse."[1] This is where he found refuge with Paul Bernard, another exile. It is speculated that during this time in Spain, particularly Barcelona, Ravachol learned how to make bombs. In August, 1891, he traveled to Paris using a fake name and "met up with other Paris anarchists." At this meeting, he met Henri Louis Descamps' wife, Descamps being someone who was arrested during a demonstration in Clichy on 1 May 1891.

Ravachol was aroused to take action in 1892 against members of the judiciary, because of the trial outcomes for the rioters at Clichy on 1 May 1891. After stealing "dynamite from a quarry," Ravachol placed bombs in the living quarters of the Advocate General, Léon Bulot (executive of the Public Ministry), and Edmond Benoît, the councillor who had presided over the Assize Court during the Clichy Affair, they took place on 27 March 1892 and 11 March 1892, respectively.

An informant, named Jules Lhérot, who was a waiter at the Restaurant Véry, told of Ravachol's actions because Ravachol had "spoke too freely with" Lhérot. Ravachol was arrested on 30 March 1892 for his bombings at the Restaurant Véry. The day before the trial, anarchists bombed the restaurant where the informant worked. Ravachol was tried at the Assize Court of Seine on 26 April. He was convicted and condemned to prison for life.

Trial at the Loire Assize Court

Ravachol's second trial was on 21 June 1892, before the Loire Assize Court in Montbrison, for crimes that predated the bombings. He admitted to graverobbing and to murdering Jacques Brunel, "the hermit of Chambles", in 1891, something he had never denied, but denied the other charges.[2][3] In his defence, Ravachol said that he killed to satisfy his personal needs and to aid the anarchist cause. His brother and sister supported him by testifying to his role as a father during their childhood. He was sentenced to death, and responded to the verdict with a cry of "Vive l'anarchie!"[3]

He was refused the right to read a final statement, which he gave instead to his lawyer, Lagasse: "I hope that the jurors who, by condemning me to death, have thrown into despair those who have preserved their affection for me, carry on their conscience the memory of their sentence with the lightness and courage by which I will carry my head to the blade of the guillotine."[4]

Execution

Ravachol was executed on 11 July 1892 at Montbrison. He sang Le Père Duchesne on the way to the guillotine.[3]

The myth of Ravachol

On 9 December 1893, Auguste Vaillant threw a bomb into the French Chamber of Deputies to avenge Ravachol (the explosion injured one deputy).

Ravachol became a somewhat romanticised symbol of desperate revolt and a number of French songs were composed in his honour, such as la Ravachole, to the tune of la Carmagnole. An anarchist group in Belleville, Paris in the late 1890s named themselves "The Avengers of Ravachol".[5] Strasbourg-based Situationist students active in the May 68 events in France associated their manifesto On the Poverty of Student Life with a "Society for the Rehabilitation for Karl Marx and Ravachol".

Ravachol has also appeared as a minor character in Frank Chadwick's role-playing game Space: 1889 as well as in several of his memoirs.

In 2011, an anarchist character called Claude Ravache appeared in the movie Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows. He was clearly inspired by Ravachol.

The award-winning computer game Disco Elysium is set in the fictional city of "Revachol," in the aftermath of an international coup that quashed Revachol's anarcho-communist revolution.[1][2][3]

See also

References

- ^ Chailand, Gérard; Blin, Arnaud; Hubac-Occhipinti, Olivier (2016). The History of Terrorism: From Antiquity to ISIS. University of California Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-520-29250-5.

- ^ Abidor, Mitchell (2016). Death to Bourgeois Society: The Propagandists of the Deed. PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-217-9.

- ^ a b c Maitron, Jean (2021-12-21), "RAVACHOL [KOENINGSTEIN François, Claudius, dit; souvent orthographié Koenigstein]", Dictionnaire des anarchistes (in French), Revised by Anne Steiner, Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, retrieved 2022-06-27

- ^ "Je souhaite que les jurés qui, en me condamnant à mort, viennent de jeter dans le désespoir ceux qui m'ont conservé leur affection, portent sur leur conscience le souvenir de leur sentence avec autant de légèreté et de courage que moi j'apporterai ma tête sous le couteau de la guillotine." François Koënigstein, aka "Ravachol", Le Révolté, no 40, 1-7 July 1892.

- ^ Merriman, John (2019), Levy, Carl; Adams, Matthew S. (eds.), "The Spectre of the Commune and French Anarchism in the 1890s", The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 343–352, at p. 347, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_20, ISBN 978-3-319-75619-6, S2CID 165457738, retrieved 2022-01-11

Bibliography

- Maitron, Jean. Ravachol et les anarchistes, collection Archives, 1964, 216 p. (in French)

External links

- 1859 births

- 1892 deaths

- People from Saint-Chamond

- Executed anarchists

- French anarchists

- People executed by guillotine

- Executed French people

- People executed by the French Third Republic

- Anarchist assassins

- French revolutionaries

- People executed by France by decapitation

- Executed people from Rhône-Alpes

- Executed revolutionaries