Synclavier

The Synclavier is an early digital synthesizer, polyphonic digital sampling system, and music workstation manufactured by New England Digital Corporation of Norwich, Vermont. It was produced in various forms from the late 1970s into the early 1990s. The instrument has been used by prominent musicians.

History

The original design and development of the Synclavier prototype occurred at Dartmouth College with the collaboration of Jon Appleton, Professor of Digital Electronics, Sydney A. Alonso, and Cameron Jones, a software programmer and student at Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering.

Synclavier I

First released in 1977–78,[1][2][3] it proved to be highly influential among both electronic music composers and music producers, including Mike Thorne, an early adopter from the commercial world, due to its versatility, its cutting-edge technology, and distinctive sounds.

The early Synclavier I used FM synthesis, re-licensed from Yamaha,[3][a] and was sold mostly to universities. The initial models had only a computer and synthesis modules; later models added a musical keyboard and control panel.

Synclavier II

The system evolved in its next generation of product, the Synclavier II, which was released in early 1980 with the strong influence of music producer Denny Jaeger of Oakland, California. It was originally Jaeger's suggestion that the FM synthesis concept be extended to allow four simultaneous channels or voices of synthesis to be triggered with one key depression to allow the final synthesized sound to have much more harmonic series activity. This change greatly improved the overall sound design of the system and was very noticeable. 16-bit user sampling (originally in mono only) was added as an option in 1982. This model was succeeded by the ABLE Model C computer based PSMT in 1984 and then the Mac-based 3200, 6400 and 9600 models, all of which used the VPK keyboard.

Keyboard controller

Synclavier II models used an on/off type keyboard (called the "ORK") while later models, labeled simply "Synclavier", used a weighted velocity- and pressure-sensitive keyboard (called the "VPK") that was licensed from Sequential Circuits and used in their Prophet-T8 synthesizer.

Digital sampling

The company evolved the system continuously through the early 1980s to integrate the first 16-bit digital sampling system to magnetic disk, and eventually a 16-bit polyphonic sampling system to memory, as well. The company's product was the only digital sampling system that allowed sample rates to go as high as 100 kHz.

Tapeless studio concept

Ultimately, the system was referred to as the Synclavier Digital Recording "Tapeless Studio" system among many professionals. It was a pioneer system in revolutionizing movie and television sound effects and Foley effects methods of design and production starting at Glen Glenn Sound. Although pricing made it inaccessible for most musicians (a Synclavier could cost anywhere from $25,000 to $200,000),[5][6] it found widespread use among producers and professional recording studios, competing at times in this market with high-end production systems such as the Fairlight CMI.

Technological achievements

When the company launched and evolved its technology, there were no off-the-shelf computing systems, integrated software, nor sound cards. Consequently, all of the hardware from the company's main real-time CPU, all input and output cards, analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog cards and its memory cards were developed internally, as well as all of the software. The hardware and software of the company's real-time capability was used in other fields completely remote to music, such as the main Dartmouth College campus computing node computers for one of the USA's first campus-wide computing networks, and in medical data acquisition research projects.

End of manufacture

New England Digital ceased operations in 1993. According to Jones, "The intellectual property was bought up by a bank—then it was owned by a Canadian company called Airworks—and I bought the intellectual property and the trademark back from a second bank which had foreclosed on it from Airworks."

Reincarnations

In 2019, Jones released an iOS version of the Synclavier dubbed Synclavier Go! using much of the original code base.[7] Jones has also worked with Arturia to bring the Synclavier V software version of the instrument to their V Collection plugin suite.

Models and options

Prototype

- Dartmouth Digital Synthesizer (1973)[1]

Processor

- ABLE computer (1975): an early product of New England Digital, was a 16-bit mini-computer on two cards, using a transport-triggered architecture.[8][9] It used a variant of XPL called Scientific XPL for programming.[10] Early applications of the ABLE were for laboratory automation, data collection, and device control. The commercial version of the Dartmouth Digital Synthesizer, the Synclavier, was built on this processor.[11]

Digital synthesis cards

- The FM/Additive synthesis waveforms are produced by the Synclavier Synthesizer cards (named SS1 through SS5). Each set of these five cards produced 8 mono FM voices (later variants supported stereo). The processor handles sending start-stop-setPitch-setParameter commands to the SS card set(s), as well as handling scanning of the keyboard and control panel. There is little public documentation available on these cards, as their design was the unique asset of the Synclavier. However, their structure was similar to other digital synthesizers of the mid-late 1970s realized in Medium Scale Integration (MSI) hardware, such as the Bell Labs Digital Synthesizer.[12]

Black panel models

On 1970s–late 1980s:

- Synclavier I (1977)[2]

- Hand Operated Processor (HOP box): a troubleshooting tool for the Synclavier system, connected to ABLE computer via "D01 Front Panel Interface Card".

-

HOP box and D01 card (for interface)

-

Terminal: ADM-3A (1975)

- Synclavier II (1980): 8-bit FM/additive synthesis, 32-track memory recorder, and ORK keyboard. Earlier models were entirely controlled via ORK keyboard with buttons and wheel; a VT100 terminal was subsequently introduced for editing performances. Later models had a VT640 graphic terminal for graphical audio analysis (described below).[11]

- Original Keyboard (ORK, c.1979): original musical keyboard controller in a wooden chassis, with buttons and silver control wheel on the panel.[11]

- Sample-to-Disk (STD, c.1982): a first commercial hard disk streaming sampler, with 16-bit sampling at up to 50 kHz.[11]

- Sample-to-Memory (STM): later option to sample sounds and edit them in computer memory.[13]

- Direct-to-Disk (DTD, c.1984): an early commercial hard disk recording system.

- Signal File Manager: a software program operated via VT640 graphic terminal, enabling 'Additive Resynthesis' and complex audio analysis.[11]

- Digital Guitar Interface[14][15]

- SMPTE timecode tracking[11]

- MIDI interface[11]

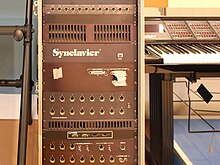

-

Rear panel of Synclavier II

-

ORK: Original Keyboard (c.1980)

-

Terminal: DEC VT100 (1978) / VT640

- Synclavier PSMT (1984): a faster ABLE Model C processor based system, with a new 'Multi-Channel-Distribution' real-time digitally controlled analog signal routing technology, and 16-bit RAM-based stereo sampling subsystem. The monaural FM voice card was doubled up and enabling software panning for stereo output was introduced.[11]

- Velocity/Pressure Keyboard (VPK, c.1984): a weighted velocity/after-pressure sensitive musical keyboard controller, was introduced. This had a black piano lacquer finished chassis, a larger display, additional buttons and a silver control wheel.[11]

-

Synclavier PSMT rack

-

VPK panel (2 of 6)

-

VPK: Velocity Pressure Keyboard (1984)

Ivory panel models

In late 1980s–1993; operated via Macintosh II as terminal.[13]

- Synclavier 3200

- Synclavier 6400

- Synclavier 9600

- Synclavier TS (Tapeless Studio): consists of Synclavier and Direct-to-Disk

- Synclavier Post Pro: consists of Direct-to-Disk

- Synclavier Post Pro SD (Sound Design): consists of small Synclavier and Direct-to-Disk

Notable users

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (November 2017) |

- Laurie Anderson is credited with using the Synclavier on her albums Mister Heartbreak (1984), United States Live (1984) and the 1986 soundtrack album Home of the Brave.

- Wally Badarou: used the Synclavier II on Level 42 and solo studio albums, as well as on the 1985 Kiss of the Spider Woman movie additional soundtrack.[16]

- Tony Banks of Genesis used a Synclavier II (ORK version) on the albums Genesis (1983) and Invisible Touch (1986) and their respective tours, along with solo albums and soundtracks of that period, notably on "Mama" and "Home by the Sea".[17]

- Christopher Boyes, supervising sound editor/sound designer for the 2009 film Avatar, used the Synclavier for blending or layering different sound effects and matching pitches.[18]

- Joel Chadabe: composer/founder of Electronic Music Foundation. In September 1977 he bought the first Synclavier without musical keyboard (ORK), and wrote custom software to control the Synclavier via various devices.[2]

- Suzanne Ciani used a Synclavier to design sounds for the Bally Xenon pinball game released in 1980.[19]

- The Church used it on "Under the Milky Way" (1988). The way it is arranged gives a sound similar to bagpipes.[20]

- Chick Corea used the Synclavier on various Elektric Band albums from 1986 to 1991 as well as various Elektric Band tours.[21]

- Crimson Glory used acoustic drums blended with Synclavier-sampled drums on their 1988 album Transcendence.[22][unreliable source?]

- Paul Davis: singer/songwriter,[23] producer at Monarch Sound in Atlanta.[24]

- Depeche Mode had access to producer Daniel Miller's Synclavier, which was responsible for the character of the sound of the albums Construction Time Again (1983), Some Great Reward (1984) and Black Celebration (1986).[25]

- Vince DiCola: used the Synclavier extensively in creating studio albums; also for soundtracks Rocky IV (1985) and The Transformers: The Movie (1986).[26]

- Duran Duran used a Synclavier on the 1984 single "The Reflex".[27]

- Patrick Gleeson: film score composer. Used the Synclavier to score Apocalypse Now (1979) and The Plague Dogs (1982).[28]

- Lourett Russell Grant used a Synclavier on the 1979 disco hit "Hot to Trot".[29]

- Paul Hardcastle: composer and musician.[30]

- Robert Henke: composer, musician and software engineer. Often recording under the moniker Monolake, Henke renovated a Synclavier II and used sampled FM from it on various releases.[31]

- Michael Hoenig: film scoring work on the Synclavier, including the 1986 action-fantasy film, The Wraith.[32]

- Trevor Horn: used the Synclavier to produce records by Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Yes, and Grace Jones' 1985 album Slave to the Rhythm, among others.[33]

- Michael Jackson: particularly on his 1982 album Thriller, programming by Steve Porcaro, Brian Banks, and Anthony Marinelli. The gong sound at the beginning of "Beat It" comes courtesy of the Synclavier.[34] The Synclavier was extensively used on Jackson's 1987 album Bad and on its accompanying tour, programmed and played by Christopher Currell.[35] The Synclavier was also used by Andrew Scheps to slice and edit Jackson's beatboxing on his 1995 album HIStory.[36]

- Eddie Jobson: the 1985 album Theme of Secrets was completely made with a Synclavier.[37][38][39]

- Shane Keister: used in the 1987 American comedy film Ernest Goes to Camp.[40][41]

- Mark Knopfler: Used on the scores for the films The Princess Bride (1987) and Last Exit to Brooklyn (1989), in which all sounds except guitar (and in the latter case, violins) were produced by the Synclavier. The Synclavier is also heard on the Dire Straits albums Love over Gold (1982, played by Alan Clark), Brothers in Arms (1985, played by Guy Fletcher), and On Every Street (1991).[42]

- Kraftwerk acquired one in the early to mid 1980s and initially used it to re work the material later released as Electric Cafe / Techno Pop, and also on live performances in the 1990s.[43]

- Dave Lawson

- Mannheim Steamroller: used on most of their albums to present.[44]

- John McLaughlin used it on the albums Mahavishnu (1984) and Adventures in Radioland (1987).[45]

- Men Without Hats used on the 1984 album Folk of the 80s (Part III).[46]

- Pat Metheny: American jazz guitarist.[32]

- Walter "Junie" Morrison: used a Synclavier on his 1984 album, Evacuate Your Seats.[47]

- Mr. Mister: used Synclavier on albums I Wear the Face (1984), Welcome to the Real World (1985), and Go On... (1987).[48]

- Puscifer: the group used Synclavier on their 2020 album Existential Reckoning.[49]

- Danny Quatrochi used Synclavier on Sting's album The Dream of the Blue Turtles (1985).[50]

- Kashif Saleem, American post-disco and contemporary R&B record producer, multi-instrumentalist, also a creative consultant[51] with the New England Digital Corporation: Bass synthesizer music pioneer and an early Synclavier II avid user who used Synclavier in production, for instance, of his Grammy-nominated instrumental piece "The Mood" (1983). His innovating vocalist-related sampling methods (created using Synclavier) are still in use.[52][53]

- Howard Shore, film score composer: pictured with a Synclavier on the cover of Berklee Today, Fall 1997.[54]

- Alan Silvestri: in producing the scores for the 1980s films The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986) and Flight of the Navigator (1986).[55]

- Paul Simon: on Simon's 1983 album Hearts and Bones, Tom Coppola is credited for Synclavier for "When Numbers Get Serious", "Think Too Much (b)", "Song About the Moon", and "Think Too Much (a)"; and Wells Christie is credited with Synclavier on "Rene And Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War".[56] On his 1986 album Graceland, Simon is credited under "Synclavier" for "I Know What I Know" and "Gumboots".[57]

- Mark Snow: film and television score composer; Synclavier used on The X-Files (1993–2002).[58]

- James Stroud: producer who used a Synclavier II on many hit albums he produced.[59]

- Benny Andersson: his personal studio room is still centred around a Synclavier system — he has four systems. He’s been using it since Chess in 1985.[60]

- Tangerine Dream: used a Synclavier on several of their studio albums including Exit in 1981.[61]

- Mike Thorne: producer, one of the first musicians to buy a Synclavier; used it on records by Siouxsie and the Banshees, Soft Cell ("Tainted Love", 1981), Marc Almond, and Bronski Beat, among others.[62]

- Pete Townshend: started using the Synclavier on the recording of All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes (1982).[63]

- Triumph: Rik Emmett used a Synclavier 9600 around the period of Thunder Seven (1984) to Surveillance (1987).[64]

- Whodini: Synclavier II was used on albums Escape (1984) and Back in Black (1986).[65]

- Stevie Wonder: used a Synclavier to sample the voices of Clair Huxtable and children in an episode of The Cosby Show.[66]

- Neil Young, who used an early Synclavier II on his 1981 album Re·ac·tor, and more extensively on his uncharacteristically electronic Trans (1982).[67]

- Frank Zappa: in 1982 one of the first Synclavier owners; 1984's Thing-Fish (underscoring), Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger (1984, underscoring) and Francesco Zappa (1984, solely Synclavier); 1985's Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention (sampled sounds); 1986's Grammy-winning album Jazz from Hell ("St. Etienne" excepted, solely Synclavier); 1994's Civilization Phaze III completed in 1993 shortly before his death, released posthumously, musical portions composed and recorded exclusively using the Synclavier. Zappa also used the instrument to create the music posthumously released in 2011 on Feeding the Monkies at Ma Maison.[68]

- Marlon Jackson

See also

Notes

- ^ At the time, Yamaha was the exclusive commercial licensee from the original inventor, John Chowning at Stanford University.[4]

References

- ^ a b "History of Masters Program in Digital Musics". Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on 2009-10-12.

- ^ a b c

Joel Chadabe (May 1, 2001). "The Electronic Century Part IV: The Seeds of the Future". Electronic Musician. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009.

In September 1977, I bought the first Synclavier, although mine came without the special keyboard and control panel ...

- ^ a b "1978 New England Digital Synclavier". Mix. Penton Media. September 1, 2006.

- ^ Eric Grunwald (Summer 1994). "Bell Tolls for FM Patent, but Yamaha Sees "New Beginning"" (PDF). Stanford Technology Brainstorm. Vol. 3, no. 2. Office of Technology Licensing (OTL), Stanford University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-05. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

The technique for synthesizing electronic music, invented by Music Professor John Chowning, brought in over $20 million through an exclusive license to Yamaha Corporation of Japan, which used the technology in its DX-7 synthesizer, enormously popular in the 1980s.

- ^ "New England Digital Synclavier - Vintage Synth Explorer". www.vintagesynth.com.

- ^ synthhead (20 May 2016). "$200,000 Synclavier Synthesizer Now A $200 App". synthtopia.com.

- ^ Neal Andrew Emil Gustafson (27 March 2019). "Synthesis Pioneer Cameron Jones Talks History and Making A New Synclavier". >Musician's Friend. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020.

- ^ ABLE Series Hardware Reference Manual. New England Digital Corporation, 110pp. 1978.

- ^ Creating Programs for ABLE Series Computers. New England Digital Corporation, 1978, 39pp. 1978.

- ^ Scientific XPL for New England Digital Corporation's ABLE Series Computers. New England Digital Corporation, 1978, 74pp. 1978.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Synclavier Early History". Synclavier European Services.

- ^ "Synclavier Hardware". Synhouse Multimedia.

- ^ a b Synclavier Manual III Reference Guide (PDF). Vol. III. Synclavier Digital. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- ^ a b Nicholas Webb, "Interview with Roland GR User Pat Metheny", Roland GR-300 Modification and More, Wayne Scott Joness (Composer)

- ^ a b "Roland G-303 Guitar Synthesizer Controller", Roland GR-300 Modification and More, Wayne Scott Joness (Composer)

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, May 1986, p. 69

- ^ "Keyboard". Tony Banks unofficial website. lakeofsilence.de.

- ^ Blair Jackson (Jan 1, 2010). "Avator – Jame Cameron and Audio Team Create a New World of Futuristic Sounds". Mix. Penton Media. Archived from the original on 2010-07-13.

- ^ "Omni-Suzanne Ciani". YouTube.

- ^ Lurie, Robert Dean (2009). No Certainty Attached: Steve Kilbey and The Church. Portland OR: Verse Chorus Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-89124-122-2.

- ^ Darter, Tom; Doerschuk, Bob (2008). "The state of the artist". In Ernie Rideout (ed.). Keyboard Presents the Best of the '80s: The Artists, Instruments, and Techniques of an Era. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 15–19. ISBN 978-0-87930-930-5.

- ^ "Crimson Glory - Transcendence". Maximum Metal. December 1, 2007.

- ^

"yahoo groups interview with Paul Davis". 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Droney, Maureen (September 1, 2001). "Dave Hard Drive Pensado". Mix. Los Angeles: Penton Media. Archived from the original on April 14, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ "Remixing Depeche Mode". roberthenke.com.

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, May 1985, p. 40

- ^ "Interview With Nile Rodgers". Journal on the Art of Record Production. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^

"Synth Pioneers: Patrick Gleeson". 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Lourett Russell Grant". Lourettrussellgrant.com.

- ^

"list of synclavier users". 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

"Studio".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Amato, Mia (July 12, 1986). "NED Synclavier Seminar Offers Sound Solutions". Billboard. Vol. 98, no. 28. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 40. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Warner, Timothy (2003). Pop music: technology and creativity : Trevor Horn and the digital revolution. Ashgate popular and folk music. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-7546-3132-X.

- ^ Milner, Greg (2009). Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music. Macmillan. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-571-21165-4.

- ^

"The Third Dimension". SPIN. 7 (4). SPIN Media LLC: 26. July 1991. ISSN 0886-3032.

Christopher Currell, the Los Angeles- based Synclavier performer and engineer on Michael Jackson's Bad album

- ^ "Gearslutz - "Post here if you worked on Michael Jackson's DANGEROUS album"".

- ^

"unknown". Keyboard. 12. GPI Publications: 24. 1986. ISSN 0730-0158.

Eddie Jobson / Theme of Secrets / Jobson is one of those highly talented keyboard players ... this time it's strictly Jobson and a Synclavier-a boy and his synthesizer.

[verification needed] - ^

"unknown". Schwann Spectrum. 2 (3~4). ABC Consumer Magazines: 338. 1991.

Jobson, Eddie Jobson, Eddie -Theme Of Secrets (music for Synclavier) Pnvale Music

[verification needed] - ^ Private Music (March 1988). "Advertisement: Private Artists". Spin. Vol. 3, no. 10. p. 33. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^

"United States". Keyboard. 13 (7~12). GPI Publications: 30. 1987. ISSN 0730-0158.

Nashville synthesist Shane Keister, using a Fairlight and Synclavier, scored Ernest Goes To Camp, the just-released ...

[verification needed] - ^ The ending titles of the movie

- ^

Musician (153–158). Amordian Press: 34. 1991.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[verification needed] - ^ Bussy, Pascal (2004). Kraftwerk: Man, Machine and Music. SAF Publishing Ltd.

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, Sept 1995, p. 32

- ^ Stump, Paul (2000). Go ahead John: the music of John McLaughlin. SAF Publishing Ltd. pp. 173–174. ISBN 0-946719-24-1.

- ^ "We will always remember the things we can never forget". www.menwithouthats.com.

- ^ "io9 Talks to Junie About P-Funk and Aliens". 18 January 2008.

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, Dec 1987, p. 31

- ^ "Existential Reckoning - (2020)". Puscifer.

- ^ "Review: The Dream of the Blue Turtles". Stereo Review. 50 (1). CBS Magazines: 154. 1985.

- ^ Harry, Weinger (20 Oct 1984). "Kashif Juggles Multi-Layered". Billboard. Vol. 96. p. 42.

- ^ [Q&A: Kashif – Music History in the Making http://soultrain.com/2012/01/23/qa-kashif-music-history-in-the-making/] (January 23, 2012). Soul Train. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ^ Kashif | Biography | AllMusic.com. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 2014-04-24

- ^ "(cover page)" (PDF), Berklee Today, vol. 9, Berklee college of music, Fall 1997, p. 1

- ^ Hagen, Earle (1990). Advanced techniques for film scoring: a complete text. Alfred Music Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 0-88284-447-4.

- ^ "Wells Christie's biography". WellsChristie.com.

- ^ "Paul Simon – Graceland". Discogs. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Trynka, Paul (1996). Rock Hardware. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-87930-428-7.

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, Aug 1983, p. 32

- ^ Schoepe, Zenon (April 2011). "Benny Anderson" (PDF). resolution. pp. 32–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Electronics & Music Maker, Jan 1982, p. 52

- ^ Milner 2009, p. 345.

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, Aug 1981, p. 28

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, July 1986, p.42

- ^ Keyboard Magazine, Nov 1986, p. 42

- ^ "the cosby show_stevie wonder's recording session". YouTube.

- ^ "NeilYoung.com: Trans". neilyoung.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-26. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- ^ Lowe, Kelly Fisher (2007). The Words and Music of Frank Zappa. Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-0-8032-6005-4.

Further reading

External links

- "What Makes The Synclavier So Special And Different?" Steve Hills, Synclavier European Services

- "Synclavier Digital's About Page"