Tietze syndrome

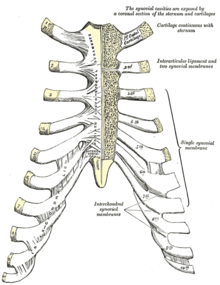

Tietze syndrome is a benign inflammation of one or more of the costal cartilages. It was first described in 1921 by German surgeon Alexander Tietze and was subsequently named after him. The condition is characterized by tenderness and painful swelling of the anterior (front) chest wall at the costochondral (rib to cartilage), sternocostal (cartilage to sternum), or sternoclavicular (clavicle to sternum) junctions. Tietze syndrome affects the true ribs and has a predilection for the 2nd and 3rd ribs, commonly affecting only a single joint.

In environments such as the emergency department, an estimated 20-50% of non-cardiac chest pain is due to a musculoskeletal cause.[1] Despite musculoskeletal conditions such as Tietze syndrome being a common reason for visits to the emergency room, they are frequently misdiagnosed as angina pectoris, pleurisy, and other serious cardiopulmonary conditions due to similar presentation. Though Tietze syndrome can be misdiagnosed, life-threatening conditions with similar symptoms such as myocardial infarction (heart attack) should be ruled out prior to diagnosis of other conditions.

Tietze syndrome is often confused with costochondritis. Tietze syndrome is differentiated from costochondritis by swelling of the costal cartilages, which does not appear in costochondritis. Additionally, costochondritis affects the 2nd to 5th ribs while Tietze syndrome typically affects the 2nd or 3rd rib.

Presentation

Tietze syndrome typically presents unilaterally at a single joint of the anterior chest wall, with 70% of patients having tenderness and swelling on only one side, usually at the 2nd or 3rd rib.[2][3] Research has described the condition to be both sudden[4] and gradual, varying by the individual.[5][6] Pain and swelling from Tietze syndrome are typically chronic and intermittent and can last from a few days to several weeks.[6]

The most common symptom of Tietze syndrome is pain, primarily in the chest, but can also radiate to the shoulder and arm.[2][6] The pain has been described as aching, gripping, neuralgic, sharp, dull, and even described as "gas pains".[3] The symptoms of Tietze syndrome have been reported to be exacerbated by sneezing, coughing, deep inhalation, and overall physical exertion.[5][7] Tenderness and swelling of the affected joint are important symptoms of Tietze syndrome and differentiate the condition from costochondritis.[8][9] It has also been suggested that discomfort can be further aggravated due to restricted shoulder and chest movement.[10]

Cause

The true etiology of Tietze syndrome has not been established, though several theories have been proposed. One popular theory is based on observations that many patients begin developing symptoms following a respiratory infection and dry cough, with one study finding 51 out of 65 patients contracted Tietze syndrome after either a cough or respiratory infection.[3][11][12] Thus, it has been hypothesized that the repetitive mild trauma of a severe cough from a respiratory infection may produce small tears in the ligament called microtrauma,[6][13] causing Tietze syndrome.[12][14] However, this theory is disputed as it does not account for symptoms such as the onset of attacks while at rest as well as the fact that swelling sometimes develops before a cough.[11][13][15] The respiratory infection has also been observed accompanying rheumatoid arthritis[6][12] which, coupled with leukocytosis,[2][16] neutrophilia,[12] c-reactive protein (CRP),[16] and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),[9][12] suggest an infectious and rheumatoid factor, though the evidence is conflicting.[15] Many theories such as malnutrition,[17][18] chest trauma,[10] and tuberculosis,[17] were thought to be among the potential causes but have since been disproven or left unsupported.[4][12][14]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis for Tietze syndrome is primarily a clinical one, though some studies suggest the use of radiologic imaging.[1][19] Musculoskeletal conditions are estimated to account for 20-50% of non-cardiac related chest pain in the emergency department.[1] Ruling out other conditions, especially potentially life-threatening ones such as myocardial infarction (heart attack) and angina pectoris, is extremely important as they can present similarly to Tietze syndrome.[8] These can usually be ruled out with diagnostic tools such as an electrocardiogram and a physical examination showing reproducible chest wall tenderness, .[1][6] After eliminating other possible conditions, physical examination is considered the most accurate tool in diagnosing Tietze syndrome. Physical examination consists of gentle pressure to the chest wall with a single finger to identify the location of the discomfort.[2] Swelling and tenderness upon palpation at one or more of the costochondral, sternocostal, or sternoclavicular joints, is a distinctive trait of Tietze syndrome and is considered a positive diagnosis when found.[2][3]

There are some pathological features that can be observed with Tietze syndrome, including degeneration of the costal cartilage, increase in vascularity, and hypertrophic changes (enlarged cells).[20] However, these features can only be identified from a biopsy.[8] Some studies have begun exploring and defining the use of radiographic imaging for diagnosing Tietze syndrome. This includes computed tomography (CT),[21] magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),[22] bone scintigraphy,[23] and ultrasound,[24] though these are only case studies and the methods described have yet to be thoroughly investigated.[22] Methods such as plain radiographs, better known as an x-ray, are helpful in the exclusion of other conditions, but not in the diagnosis of Tietze syndrome.[6][8] Some researchers believe that ultrasound is superior to other available imaging methods, as it can visualize the increased volume, swelling, and structural changes of the costal cartilage.[2][8]

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of Tietze syndrome can display as a wide variety of conditions, making it difficult to diagnose, especially to physicians unaware of the condition.[10] Due to its presentation, Tietze syndrome can be misdiagnosed as a number of conditions, including myocardial infarction (heart attack), angina pectoris, and neoplasms.[6][8][10]

Costochondritis is most commonly confused with Tietze syndrome, as they have similar symptoms and can both affect the costochondral and sternocostal joints. Costochondritis is considered a more common condition and is not associated with any swelling to the affected joints, which is the defining distinction between the two.[2][5] Tietze syndrome commonly affects the 2nd or 3rd rib and typically occurs among a younger age group,[2] while costochondritis affects the 2nd to 5th ribs and has been found to occur in older individuals, usually over the age of 40. In addition, ultrasound can diagnose Tietze syndrome, whereas costochondritis relies heavily on physical examination and medical history.[8]

Another condition that can be confused for Tietze syndrome and costochondritis is slipping rib syndrome (SRS). All three conditions are associated with chest pain as well as inflammation of the costal cartilage.[25] Unlike both costochondritis and Tietze syndrome, which affect some of the true ribs (1st to 7th), SRS affects the false ribs (8th to 10th). SRS is characterized by the partial dislocation, or subluxation, of the joints between the costal cartilages.[26] This causes inflammation, irritated intercostal nerves, and straining of the intercostal muscles. SRS can cause abdominal and back pain, which costochondritis does not.[27] Tietze syndrome and SRS can both present with radiating pain to the shoulder and arm, and both conditions can be diagnosed with ultrasound, though SRS requires a more complex dynamic ultrasound.[28]

The vast differential diagnosis also includes:

- Pleural diseases including pleurisy, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, and pneumothorax.[8][6]

- Rheumatic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and rheumatic fever.[9]

- Arthritis of the costal cartilages, including rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis (pyogenic), monoarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis.[1][6][13]

- Neoplasms, both benign and malignant (cancerous), including chondroma, osteochondroma, multiple myeloma, osteosarcoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and carcinoma.[3][11]

- Nerve pain, specifically intercostal neuritis and intercostal neuropathy.[8][14]

- Aortic dissection, a serious condition involving a tear in the body's largest artery.[29]

Treatment

Tietze syndrome is considered to be a self-limiting condition that usually resolves within a few months with rest.[3] Management for Tietze syndrome usually consists of analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, aspirin, acetaminophen (paracetamol), and naproxen.[29] Other methods of management include manual therapy and local heat application.[1][14] These are intended to relieve pain and are not expected to treat or cure Tietze syndrome as the condition is expected to resolve on its own.

Intercostal nerve block

A nerve block can be utilized in cases where symptom management is not satisfactory in relieving pain.[2][5] This is usually a nerve-blocking injection that consists of a combination of steroids such as hydrocortisone, and anesthetics such as lidocaine and procaine, which is typically administered under ultrasound guidance.[6][8] One study used a combination of triamcinolone hexacetonide and 2% lidocaine in 9 patients and after a week, found an average 82% decrease in size of the affected costal cartilage when assessing with ultrasound as well as a significant improvement of symptoms clinically.[24] However, the long-term effectiveness of the injection is disputed, with multiple researchers describing recurrence of symptoms and repetitive injections.[6][29]

Surgical intervention

In refractory cases of Tietze syndrome, where the condition is resistant to other conservative treatment options, surgery is considered.[2][3] Surgery is uncommon for cases of Tietze syndrome, as many describe Tietze syndrome as manageable under less invasive options.[10] The use of surgery in this context refers to the resection of the affected costal cartilages and some of the surrounding areas.[2] Some surgeons have resected cartilage matching the symptoms of Tietze syndrome under the assumption the cartilage was tubercular.[4] One study describes a case in which surgeons resected a large amount of cartilage, including minutely hypertrophied tissue, as a previous resection failed to relieve symptoms which is believed to be due to improperly resected margins.[29] There is limited literature on surgical treatment of this disease,[30] and overall research on the treatment of severe, chronic forms of Tietze syndrome.[29]

History

Tietze syndrome was named after and first described in 1921 by German surgeon Alexander Tietze.[17] Tietze first cited 4 cases in Germany of painful swelling where he originally believed the condition was as a result of tuberculosis or wartime malnutrition.[18]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Sawada K, Ihoriya H, Yamada T, Yumoto T, Tsukahara K, Osako T, et al. (2019). "A patient presenting painful chest wall swelling: Tietze syndrome". World Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10 (2): 122–4. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2019.02.011. PMC 6340818. PMID 30687451.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rokicki W, Rokicki M, Rydel M (September 2018). "What do we know about Tietze's syndrome?". Kardiochirurgia I Torakochirurgia Polska = Polish Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 15 (3): 180–2. doi:10.5114/kitp.2018.78443. PMC 6180027. PMID 30310397.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kayser HL (December 1956). "Tietze's syndrome; a review of the literature". The American Journal of Medicine. 21 (6): 982–9. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(56)90111-5. PMID 13372573.

- ^ a b c Geddes AK (December 1945). "Tietze's Syndrome". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 53 (6): 571–3. PMC 1582475. PMID 20323631.

- ^ a b c d Stochkendahl MJ, Christensen HW (March 2010). "Chest pain in focal musculoskeletal disorders". The Medical Clinics of North America. 94 (2): 259–73. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.01.007. PMID 20380955.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Levey GS, Calabro JJ (June 1962). "Tietze's syndrome: Report of two cases and review of the literature". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 5 (3): 261–9. doi:10.1002/art.1780050306.

- ^ Bernreiter M (July 1956). "Tietze's syndrome". Annals of Internal Medicine. 45 (1): 132–4. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-45-1-132. PMID 13340574.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Do W, Baik J, Kim ES, Lee EA, Yoo B, Kim HK (April 2018). "Atypical Tietze's Syndrome Misdiagnosed as Atypical Chest Pain: Letter to the Editor". Pain Medicine. 19 (4): 813–5. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx213. PMID 29025153.

- ^ a b c Jurik AG, Graudal H (January 1988). "Sternocostal joint swelling--clinical Tietze's syndrome. Report of sixteen cases and review of the literature". Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 17 (1): 33–42. doi:10.3109/03009748809098757. PMID 3285453.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy AC (September 1957). "Tietze's syndrome; an unusual cause of chest wall swelling". Scottish Medical Journal. 2 (9): 363–5. doi:10.1177/003693305700200904. PMID 13467305. S2CID 7942778.

- ^ a b c Landon J, Malpas JS (September 1959). "Tietze's syndrome". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 18 (3): 249–54. doi:10.1136/ard.18.3.249. PMC 1007107. PMID 14413814.

- ^ a b c d e f Motulsky A, Rohn RJ (June 1953). "Tietze's syndrome; cause of chest pain and chest wall swelling". Journal of the American Medical Association. 152 (6): 504–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1953.03690060020007. PMID 13044558.

- ^ a b c Kim DC, Kim SY, Kim BM (2020). "Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MR Imaging of Tietze's Syndrome: a Case Report". Investigative Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 24 (1): 55. doi:10.13104/imri.2020.24.1.55. S2CID 216159576.

- ^ a b c d Wehrmacher WH (February 1955). "Significance of Tietze's syndrome in differential diagnosis of chest pain". Journal of the American Medical Association. 157 (6): 505–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1955.02950230019009. PMID 13221462.

- ^ a b Ishibashi A, Nishiyama Y, Endo M, Kawaji W, Kato T (April 1977). "Orthopedic symptoms in pustular bacterid (pustulosis palmaris et plantaris): Tietze's syndrome and arthritis of manubriosternal joint due to focal infection". The Journal of Dermatology. 4 (2): 53–9. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.1977.tb01011.x. PMID 15461326. S2CID 13298760.

- ^ a b Karabudak O, Nalbant S, Ulusoy RE, Dogan B, Harmanyeri Y (October 2007). "Generalized nonspecific pustular lesions in Tietze's syndrome". Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 13 (5): 300–1. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181581e1b. PMID 17921807.

- ^ a b c Tietze A (1921). "Über eine eigenartige Häufung von Fällen mit Dystrophie der Rippenknorpel" [About a strange accumulation of cases with dystrophy of the costal cartilage]. Berliner klinische Wochenschrift (in German). 58: 829–31.

- ^ a b McSweeny, AJ (September 1958). "Treatment of Tietze Disease with Prednisolone". Archives of Internal Medicine. 102 (3): 459–461. doi:10.1001/archinte.1958.00030010459018. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 13570735.

- ^ Martino F, D'Amore M, Angelelli G, Macarini L, Cantatore FP (March 1991). "Echographic study of Tietze's syndrome". Clinical Rheumatology. 10 (1): 2–4. doi:10.1007/BF02208023. PMID 2065502. S2CID 40467215.

- ^ Cameron HU, Fornasier VL (December 1974). "Tietze's disease". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 27 (12): 960–2. doi:10.1136/jcp.27.12.960. PMC 475563. PMID 4141710.

- ^ Edelstein G, Levitt RG, Slaker DP, Murphy WA (February 1984). "Computed tomography of Tietze syndrome". Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 8 (1): 20–3. doi:10.1097/00004728-198402000-00004. PMID 6690519. S2CID 7068641.

- ^ a b Volterrani L, Mazzei MA, Giordano N, Nuti R, Galeazzi M, Fioravanti A (September 2008). "Magnetic resonance imaging in Tietze's syndrome". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 26 (5): 848–53. PMID 19032818.

- ^ Ikehira H, Kinjo M, Nagase Y, Aoki T, Ito H (February 1999). "Acute pan-costochondritis demonstrated by gallium scintigraphy". The British Journal of Radiology. 72 (854): 210–11. doi:10.1259/bjr.72.854.10365077. ISSN 0007-1285. PMID 10365077.

- ^ a b Kamel M, Kotob H (May 1997). "Ultrasonographic assessment of local steroid injection in Tietze's syndrome". British Journal of Rheumatology. 36 (5): 547–50. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/36.5.547. PMID 9189056.

- ^ Fares MY, Dimassi Z, Baytown H, Musharrafieh U (February 2019). "Slipping Rib Syndrome: Solving the Mystery of the Shooting Pain". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 357 (2): 168–73. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.10.007. PMID 30509726. S2CID 54554663.

- ^ Turcios, NL (March 2017). "Slipping Rib Syndrome: An elusive diagnosis". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 22: 44–6. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2016.05.003. PMID 27245407.

- ^ McMahon, LE (June 2018). "Slipping Rib Syndrome: A review of evaluation, diagnosis and treatment". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 27 (3): 183–8. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2018.05.009. PMID 30078490.

- ^ Van Tassel D, McMahon LE, Riemann M, Wong K, Barnes CE (May 2019). "Dynamic ultrasound in the evaluation of patients with suspected slipping rib syndrome". Skeletal Radiology. 48 (5): 741–51. doi:10.1007/s00256-018-3133-z. ISSN 0364-2348. PMID 30612161. S2CID 57448080.

- ^ a b c d e Gologorsky R, Hornik B, Velotta J (December 2017). "Surgical Management of Medically Refractory Tietze Syndrome". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 104 (6): e443–45. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.07.035. ISSN 0003-4975. PMID 29153814.

- ^ Garrell M, Meltzer S (November 1959). "Tietze's Syndrome: A Case Report". Diseases of the Chest. 36 (5): 560–61. doi:10.1378/chest.36.5.560. PMID 13826637.